There are some who would argue that every picture a photographer makes is a self-portrait, whether they intend it to be or not. What did this photographer mean to show us of themselves with a particular picture? What did another one unknowingly reveal? These questions resonate most fully when recalling the photographers we’ve lost each year — some better known than others, but all worthy of remembrance.

For photographers, the camera is a tool of existential negotiation. Regardless of the genre in which they work, they use the camera to mediate what is before them with what lies within. The best pictures are not a statement of fact, but a fully formed and articulated opinion. “Every man’s work,” wrote the English novelist and critic Samuel Butler, “is always a portrait of himself, and the more he tries to conceal himself the more clearly will his character appear in spite of him.”

The photographers we lost this year pursued their craft with rigor and passion. Nearly all photographed until the very end, which for some came all too soon. They lived their lives with, and to varying degrees through, their cameras.

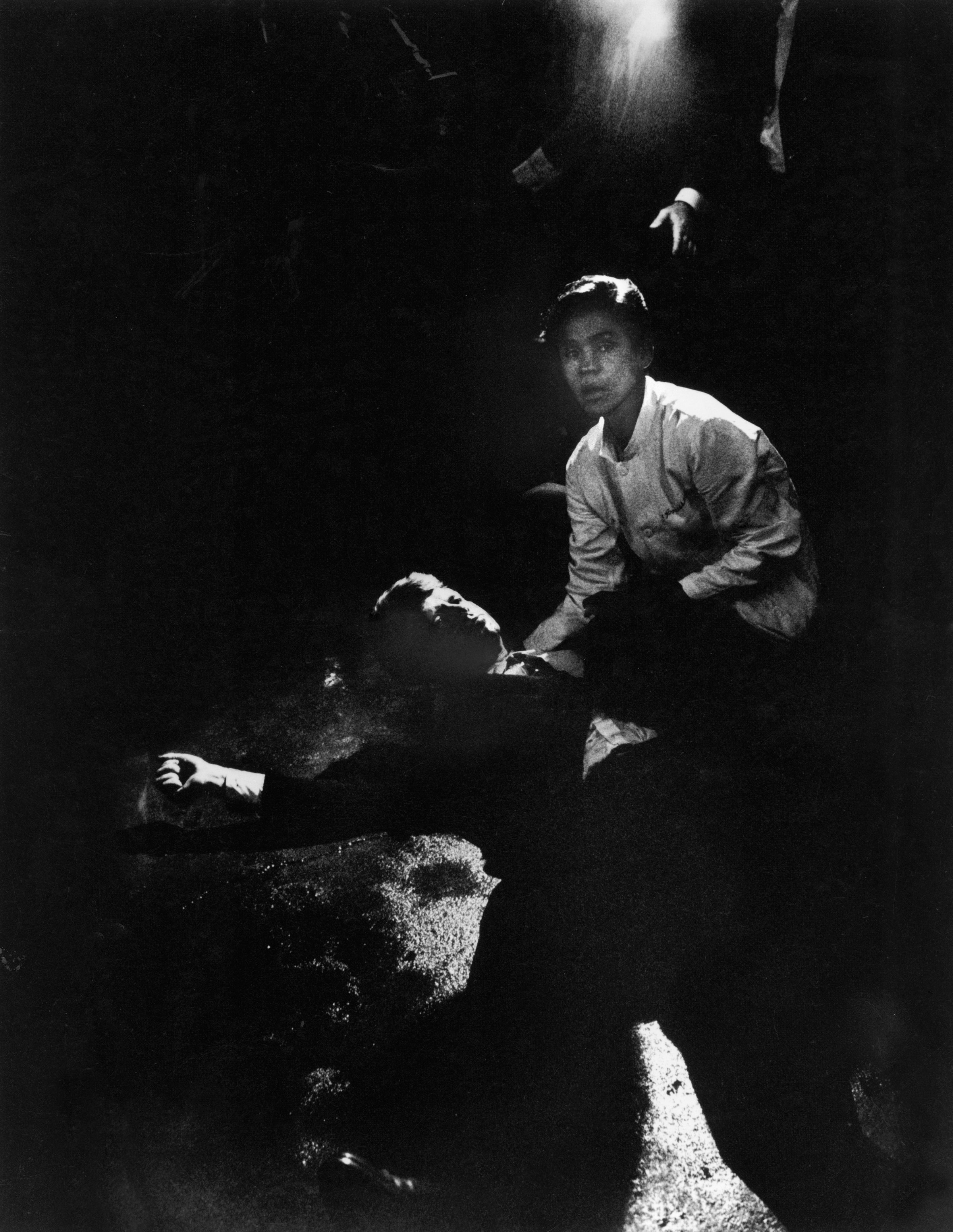

Bill Eppridge’s work is as synonymous with LIFE magazine as its iconic red and white logo. His most famous picture – the harrowing shot of a mortally wounded Robert Kennedy on the floor of a Los Angeles hotel kitchen in June 1968 — was just one of countless photos from his decades-long career that helped define the era in which he lived and worked. Bill Eppridge died in October. He was 75.

A giant in the Golden Age of advertising, Bert Stern revolutionized commercial and fashion photography in the 1950s and 60s. Stern’s iconic works, his “Last Sitting” series of Marilyn Monroe and his documentary film Jazz on a Summers’ Day, exemplify his genius as a tastemaker and cultural visionary. Stern passed away in at the age of 83.

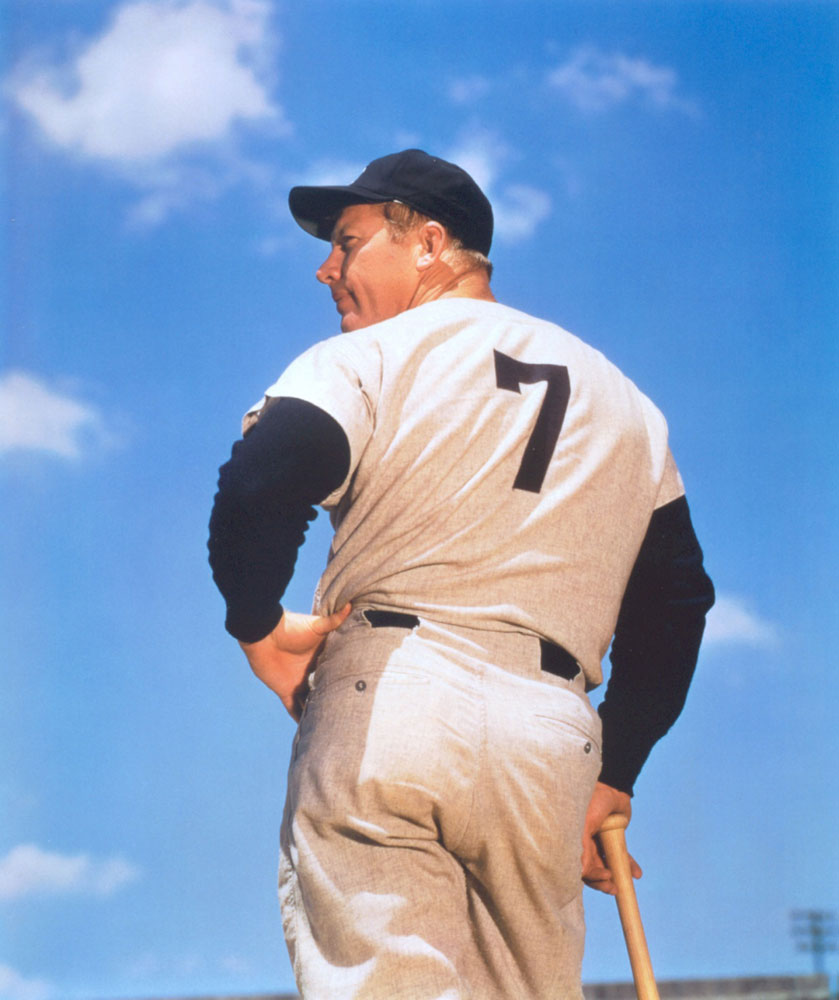

LIFE photographer John Dominis worked for the magazine for over two decades, starting with the Korean War in 1950. During his career he covered six Olympic games, the Vietnam War, the early careers of John, Robert, and Edward Kennedy, and Woodstock. He authored definitive photo essays of actors Steve McQueen, Dustin Hoffman, and singer Frank Sinatra, as well as iconic images of dancer Jacques D’Amboise and baseball player Mickey Mantle. Known for his versatility, Dominis traveled the globe while making photographs for LIFE. Of his time there, he said “…I was given all the support and money and time, whatever was required, to do almost any kind of work I wanted to do, anywhere in the world.” Dominis died at the age of 92 in December.

Wayne Miller photographed his subjects with a closeness and intimacy that belied a deep sensitivity to the world around him. He worked closely with Edward Steichen and was one of the first Americans to photograph Hiroshima after the atomic bomb. He returned from the war to Chicago where he won a Guggenheim fellowship to photograph African American life in the city’s South Side. In the 1950s, he photographed regularly for LIFE, served as chairman of the ASMP, and became a member of Magnum, where he served as president from 1962-6. He left photography in 1975 to become an advocate for the preservation of California’s forests. He died in May at the age of 94.

The subjects of Saul Leiter’s gorgeous, painterly color street photographs seem to move in a dream. Photographing in New York City in the 1950s, Leiter made his living shooting fashion for Harper’s Bazaar and Vogue; yet, his street work didn’t garner the attention that some of his contemporary’s had until the Steidl’s publication of a monograph, “Saul Leiter: Early Color,” in 2006. In his compositions he was an original; in his vision, he was symphonic. Leiter passed away in November at the age of 89.

Photojournalist Abigail Heyman passed away in June at the age of 70. One of the first female photographers inducted into Magnum and the documentary and photojournalism director at the International Center of Photography in the mid-1980s, Heyman is best known for her book Growing Up Female which included a groundbreaking photograph she took of herself undergoing an abortion. In 1981, she co-founded Archive Pictures, a cooperative photo agency, along with Charles Harbutt, Mark Godfrey, Mary Ellen Mark, and Joan Liftin. Though her work is most identified with the Feminist Movement, the specificity and deeply psychological nature of what she captured transcended the movement itself. As Ms. Liftin told the New York Times this June, “As a feminist, she was not so much about marching. She took pictures that showed what the marching was about.”

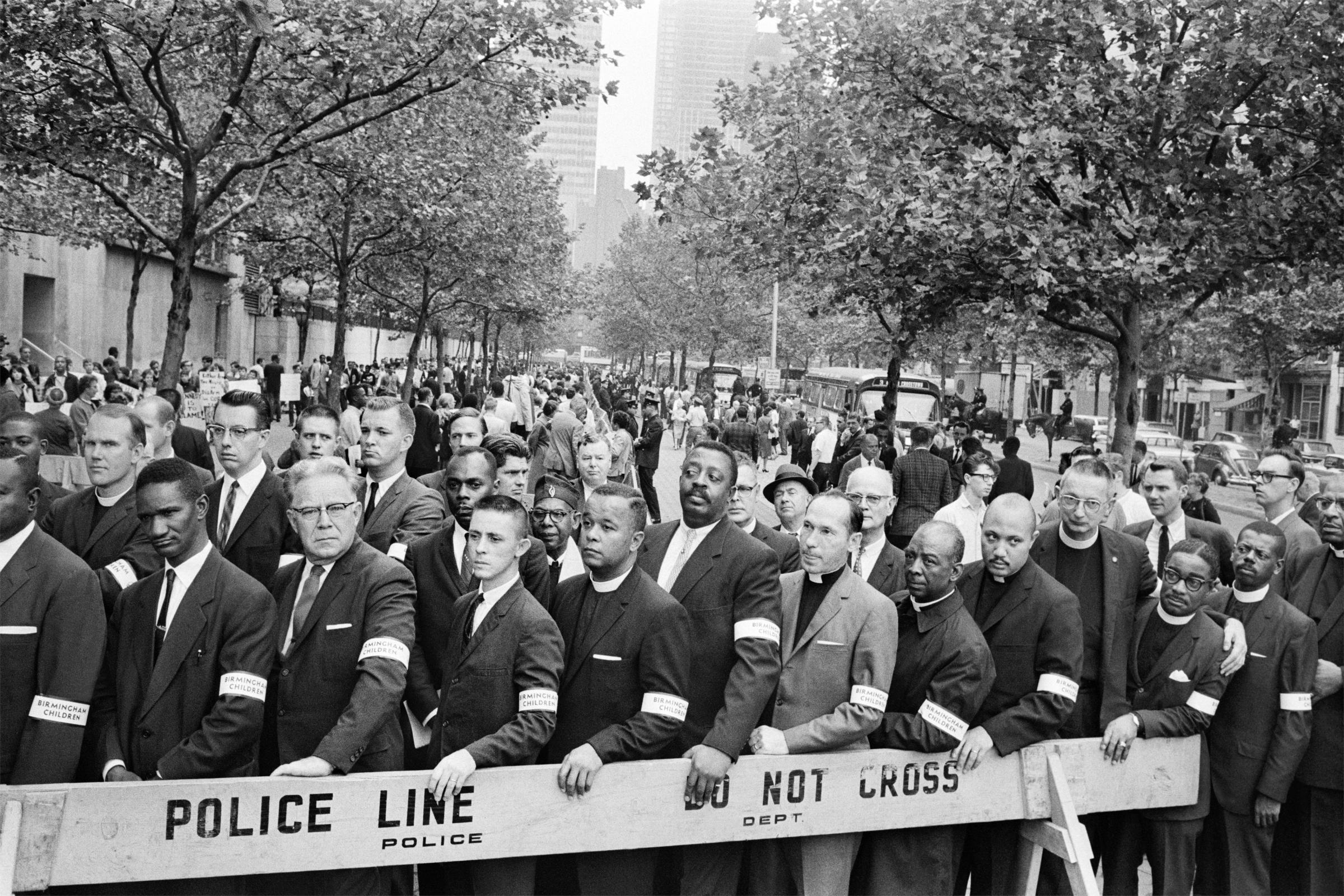

Enrique Meneses is credited with introducing the world to Fidel Castro, Che Guevara and the Cuban Revolution. Meneses’ photo essay on Castro, which landed a cover of Paris Match, was made over a period of four months between 1957-8 in Cuba’s Sierra Maestra mountains. His film was smuggled out of Cuba in a woman’s petticoat to Europe, and into the hands of his editors at Paris Match. It was the beginning of a career that spanned seven decades, and that included his coverage of the March on Washington, the Suez Crisis, the Bosnian War and other international conflicts. Meneses passed away in January at the age of 83.

Helen Brush Jenkins, one of the first female newspaper photographers, took her husband’s place at the Los Angeles Daily News in 1940s when he was called to the war. The paper’s city editor’s response to her request to fill her husband’s position was incredulous: “But you’re a woman.” Brush Jenkins replied, “I’m not a woman. I’m a photographer.” She went on to work for the newspaper for 25 years. In 1953, LIFE magazine printed her most well-known photo, a picture she took of her son Gilmer just moments after giving birth (above). She died in June at the age of 94.

Best known for his role as psychiatrist Maj. Sidney Freedman on the television series “M*A*S*H”, Allan Arbus began his career as a photographer with his wife, Diane Arbus, creating advertisements for Diane’s parents’ department store. Allan served as a photographer for the U.S. Army Signal Corps in the 1940s. Upon his return, the couple formed “Diane & Allan Arbus,” a commercial photography enterprise, with Diane as art director and Allan as the photographer. They won a contract with Conde Nast, producing over 300 pages of editorial photography for magazines such as Vogue, Glamour, and Seventeen. The never before published photo at the left of Allan and Diane in 1950 was taken during the Arbus’ time at Condé Nast. Arbus died in April. He was 95.

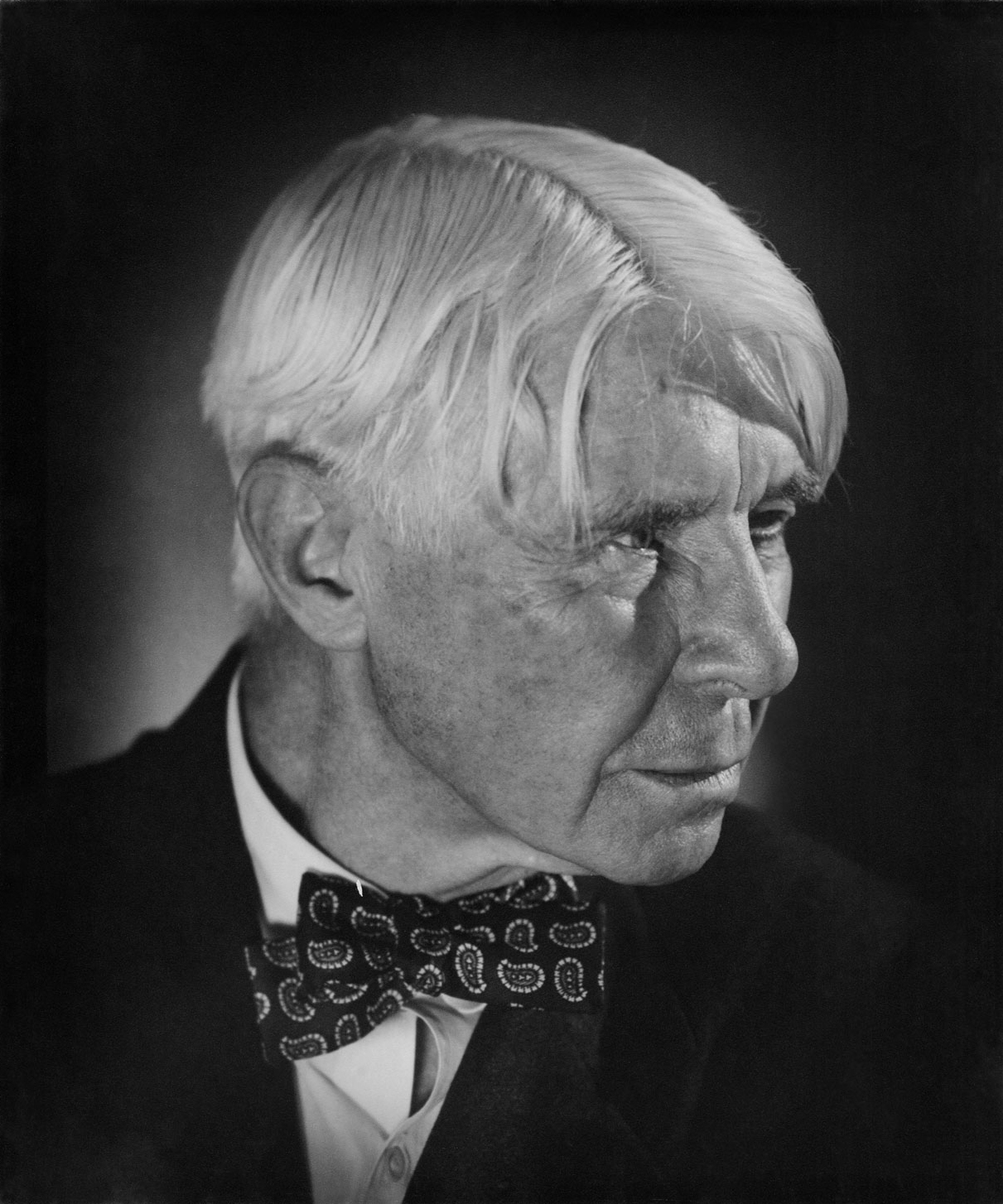

Known as the Duchess of Carnegie Hall, Editta Sherman lived and worked above the famed music hall from 1949 to 2010, when she — along with the other remaining tenants, including New York Times photographer Bill Cunningham — were pushed out in a landlord-tenant struggle. During her 61 years in the penthouse studio that was once Andrew Carnegie’s personal office, Ms. Sherman flourished as a celebrity portrait photographer. From her light-filled Manhattan studio, using a wooden Kodak 8×10 camera, Ms. Sherman created portraits of musicians, artists and actors, including Bela Lugosi, Leopold Stokowski, Carl Sandberg (above) and others. She died at the age of 101 in November.

Hungarian born Balthazar Korab made his name in the post-WWII period as a leading architectural photographer, especially in his work with Eero Saarinen. Contrary to the modus of many of his contemporaries, Korab’s photographs acknowledged the complex, human context in which buildings are placed while describing their form and shape. He passed away in January at the age of 86.

Ozzie Sweet was prolific in every sense of the word. Before he set out to be “America’s cover photographer, ” he began as an apprentice to Mount Rushmore sculptor Gutzon Borglum, and then tried his hand at acting, appearing as an extra in Cecil B. DeMille’s film “Reap the Wild Wind” starring John Wayne. Shortly after the United States entered WWII, Sweet enlisted in the army and began photographing. He made a portrait of his friend dressed up as a G.I. in training, peering over a rock with a knife between his teeth, that made its way to the cover of Newsweek. From that point on, Sweet’s photography would appear on over 1800 magazine covers, as he continued to work for Newsweek, as well as TIME, Look, Colliers, Sport, Sports Illustrated, and many, many others. As a sports photographer he made iconic images of Jackie Robinson, Yogi Berra, Joe DiMaggio, and Mickey Mantle, and considered himself to be an artist, more akin to Norman Rockwell than any contemporary photographers. He died in February at the age of 94.

Along with Helmut Newton and Guy Bourdin, Deborah Turbeville was part of the “triumvirate” that forever altered fashion photography in the 1970s. Melancholy and elegiac, Turbeville’s photographs are often described as “haunting” and focus more on her subjects than the clothing they wore. Turbeville passed away in October at the age of 81.

Visual artist and photographer Sarah Charlesworth died in June at the age of 66. A member of The Pictures Generation, Charlesworth had over 50 solo exhibitions during the course of her career, a traveling retrospective organized by SITE, and has been included in many major museum shows and collections. She was long a professor of the graduate program of S.V.A., RISD, and was named a professor at Princeton’s Lewis Center for the Arts.

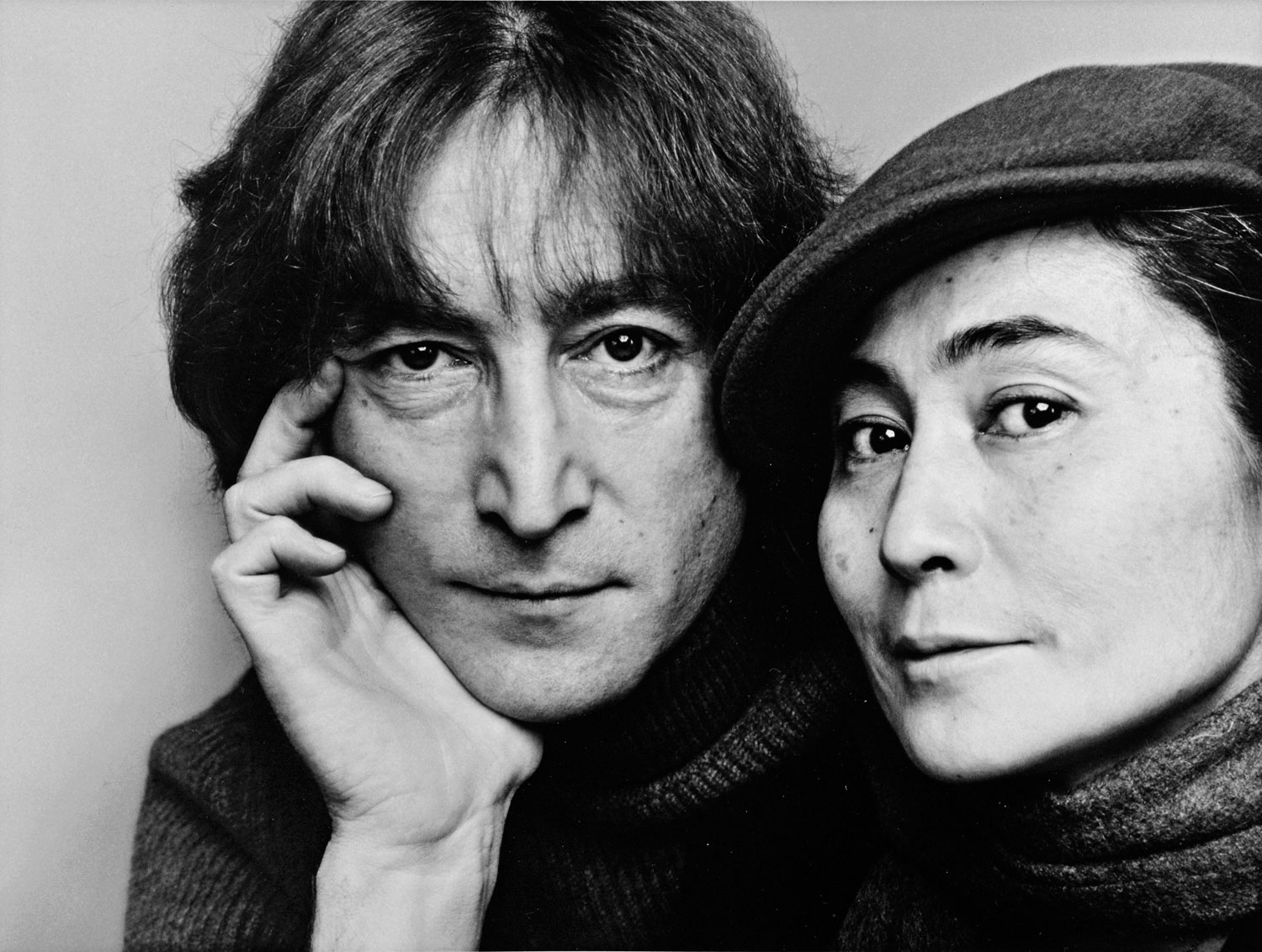

“Virtually everyone who is someone in the arts has found a path to Jack Mitchell’s photography studio on East 74th Street near First Avenue in New York,” wrote Annette Grant in a 1995 New York Times article that announced Jack Mitchell’s retirement from photography. Mitchell’s expansive 45-year career in New York City took off in 1950 when renowned dancer Ted Shawn invited him to photograph at Jacob’s Pillow. Mitchell went on to photograph the greatest dancers, actors, writers, artists and musicians of the late 20th century. He was the official photographer of the American Ballet Theater from 1960-70, and chronicled the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater for decades. In November of 1980, Mitchell photographed John Lennon and Yoko Ono for the New York Times, just weeks before Lennon was shot; an outtake of the assignment ran on People magazine’s memorial cover that December, an issue that held record sales for nearly 16 years thereafter. He died in November at 88 in his hometown of New Smyrna Beach, Fla.

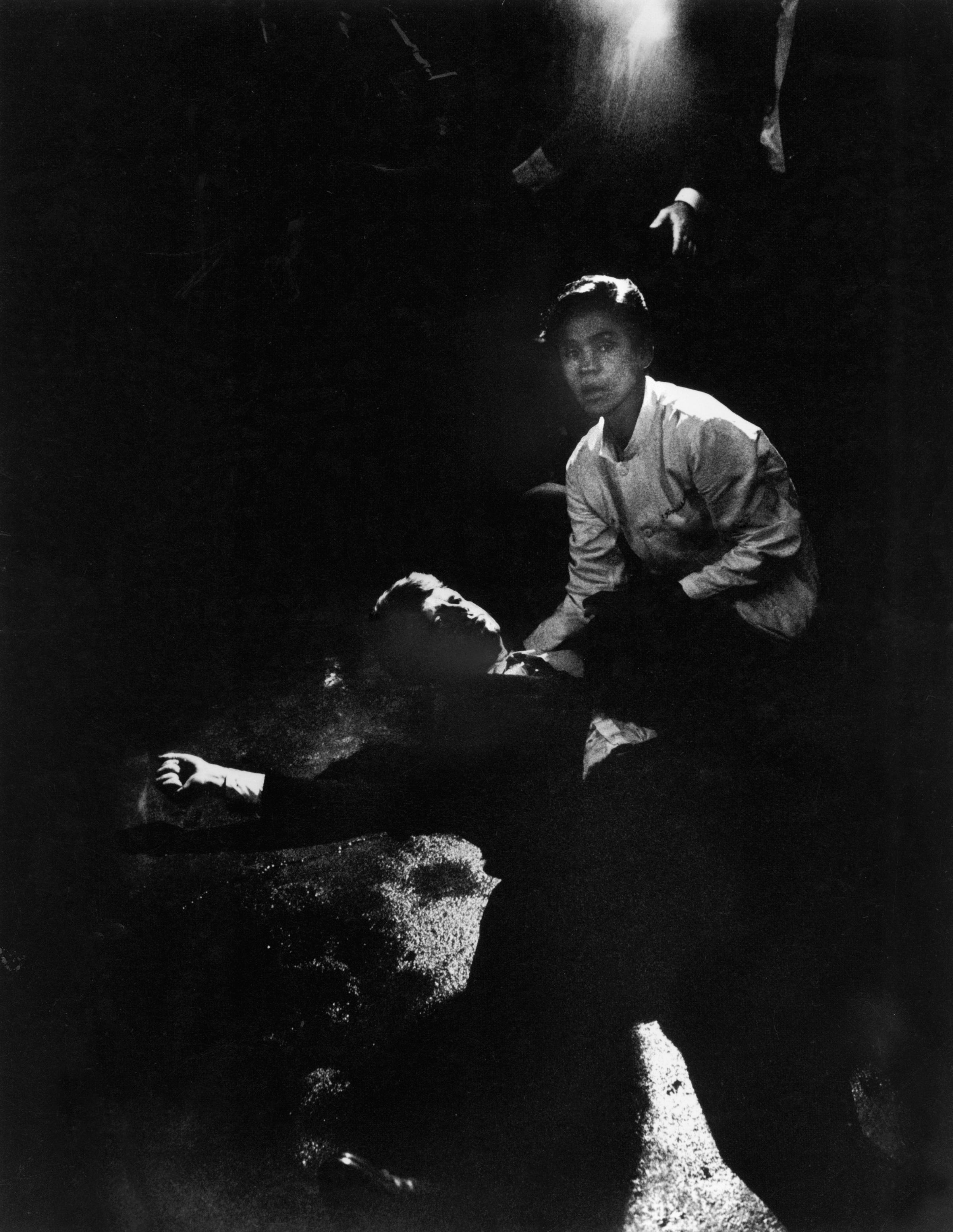

Associated Press photographer Fred Waters died in December at the age of 87. After serving in the Navy during WWII and earning a Purple Heart in Guam, Waters joined the army and trained as a photographer in Japan. He was hired by the Associated Press in 1952 and remained in Southeast Asia where he covered the Korean War, French-Indochina War, and Vietnam. During the French-Indochina War, Waters took the first photographs of Hanoi under Vietminh rule. Upon returning to the U.S. in 1962, Waters covered the Civil Rights movement, travelling with Martin Luther King, Jr. and covering the aftermath of his death. He was inducted into the Missouri Photojournalism Hall of Fame in 2008.

Imbued with a love of music and photography from a young age, Lee Tanner began photographing the jazz scene first as a young man in New York City, and later in Boston and Chicago as he travelled for work as a metallurgist, for which he held a master’s degree. Tanner had a primal understanding of jazz and of the particular genius of his subjects including Dizzy Gillespie, Chet Baker, and Duke Ellington. He captured the dark, electric atmosphere of the sessions he habitually haunted, using only available light and hand-holding his camera. In addition to his photography, Tanner also published four books of his work and briefly produced a live music show for PBS called Mixed Bag. He passed away in September at the age of 82.

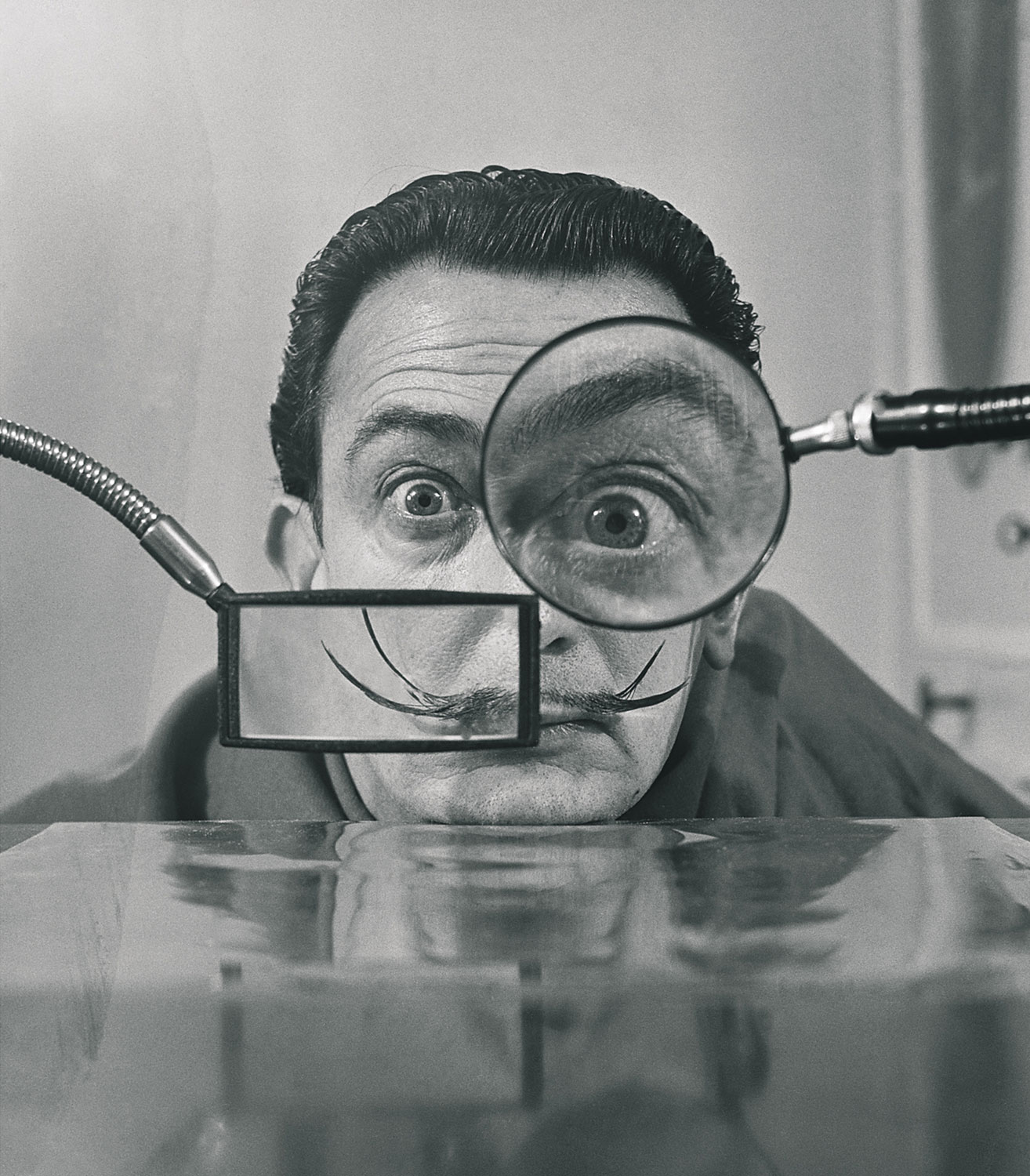

Legendary Paris Match photographers Benoit Gysembergh and Willy Rizzo passed away this year. Gysembergh was a photojournalist who began his career as a bartender at a restaurant frequented by Cartier-Bresson, Doisneau and Sieff, whose conversations he would eavesdrop on. He went on to work for Paris Match at the age of 22 under director Roger Thérond, and continued to shoot for the publication until 2012. Italian born Willy Rizzo began his career as a photojournalist, but came to be most known for his celebrity portraiture, including Salvador Dali (above), Picasso, Brigitte Bardot, and Marilyn Monroe.

Known for his kindness and meticulousness in his craft, runway photographer Piero Cristaldi worked for Gap Japan magazine for 26 years, and more recently for two years at WWD. He died at the age of 60 in June.

Haitian photojournalist Thony Belizaire dedicated nearly half of his live to covering the natural disasters and political turmoil that plagued his country for Agence France Presse, joining the agency in 1987. Haitian Prime Minister Laurent Lamothe said of Belizaire to France 24, “Mr. Belizaire devoted more than 30 years of his life to covering the major social, political and cultural events in the life of the Haitian people.” In addition to his photographic work, Belizaire founded Union of Haitian Journalists and Photographers (UJPH). He died in July at the age of 54.

Artist and critic Allan Sekula not only influenced how we understand photography, but redefined how the medium is discussed. Working between the worlds of conceptual and documentary photography and film, Sekula tackled issues of late contemporary capitalism and globalization, as in his projects Fish Story (above) and The Forgotten Space. Despite the rigor of his work, Sekula had a mischievous sense of humor as evidenced by his 1999 project Dear Bill Gates, wherein he swam as close as he could to the mogul’s house (left). During his 30-year tenure as a professor at the California Institute of the Arts, Sekula wrote with great care and passion about what he believed photography can and must do: to expose that which is and to reveal what could be. Sekula died in August at the age of 62.

More than a dozen photojournalists perished while covering the world’s conflicts in 2013. One of those, Murhaf al-Modahi, known by the pseudonym Abu Shuja, was killed in September during a shelling in a fight between rebels and troops loyal to President Bashar al-Assad in the city of Deir Ezzor in September. He was 26. Syrian photographer Molhem Barakat died in Aleppo in December while covering a battle over a hospital between Free Syrian Army rebel forces and forces loyal to Presdient Bashar al-Assad. Barakat had filed dozens of photos of the conflict in Aleppo, as well as the fractured life that continued around it, through Reuters news agency since May 2013. His age at the time of his death has not been confirmed, though he was reported to be between the ages of 17-19. Al-Modahi and Barakat are two of the more than 25 journalists who have died in Syria alone since the inception of the conflict in March 2011. Another, freelance photojournalist Olivier Voisin, died of shrapnel wounds near the city of Idlib while covering the conflict earlier this year. In an email sent to a friend shortly before his passing, Voisin expressed his fear that the war will continue for many years. Voisin died in February. He was 38.

Mia Tramz is an associate photo editor at TIME.com. Follow her on Twitter @miatramz.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Mia Tramz at mia.tramz@time.com