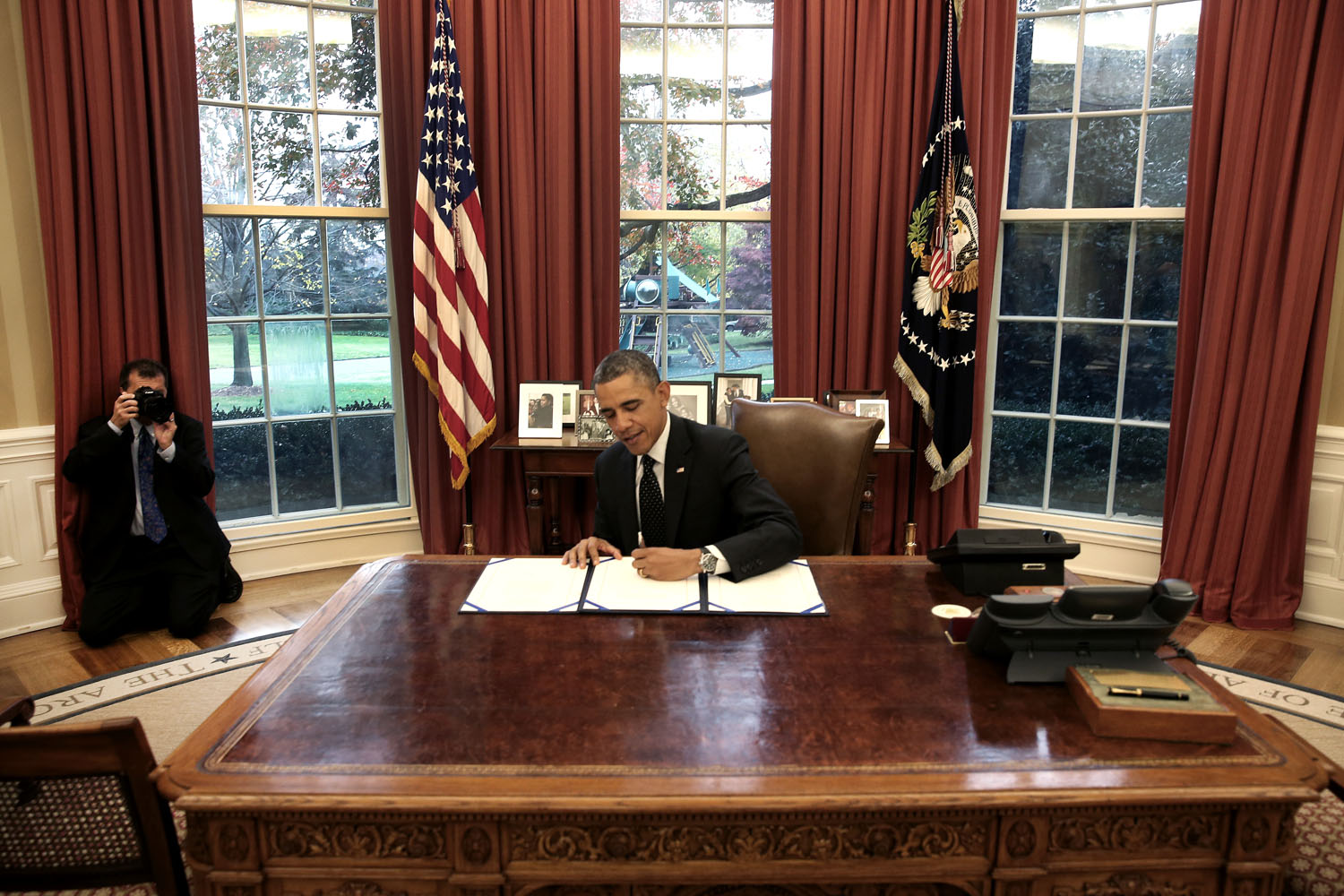

Six highly skilled, professional photographers dash into the Oval Office, a sense of practiced urgency in their assessment of how to make the most telling photo of the president, in about a minute, as he signs a document or chats with someone before continuing the real business of his job.

Then the photographers are quickly ushered out to wait for the next historic event. They are members of the White House Photo Pool doing what’s called “a spray” — arguably the least desirable type of presidential photo-op.

The question of how often and what type of access press photographers should get has been argued for as long as photographers have been in the White House, and arose once again two weeks ago with greater fervor than ever.

What drove 38 media entities to deliver a letter on Nov. 20 to Press Secretary Jay Carney to protest limits on access to the goings-on at the White House?

Photographers and directors of photography I interviewed, who as a group have photographed the past five presidents, say this administration is more restrictive than any previous in allowing media access, both as a pool and one-on-one with the president.

“They say no to everything,” New York Times photographer Stephen Crowley says of his requests to photograph the president behind the scenes.

Access is only half the issue. This administration has used social media like no other to distribute photos directly to the public. As of December 1, there were 4,951 White House Photo Office photos on Flickr, nearly all of those of the president made by Pete Souza, the director of the Photo Office and the president’s chief photographer. Each image gets between 100,000 and 200,000 views. The White House also posts to Twitter, Tumblr, Instagram and its own blog extensively, though the numbers of White House images on those sites are difficult to ascertain.

Chances are there would be less concern about access if there weren’t so many White House photos in the ether. One situation exacerbates the other. Media outlets, including TIME, regularly publish White House photos, which validates released photos and justifies restricting access, several people in the business said.

“The news organizations ran these (White House) images daily and no doubt enjoyed the fact that they were free,” said Charles Ommanney, who made pictures in the White House for Newsweek for several years. “But there was a dirty little secret that no one wanted to face up to: This was carefully edited propaganda.”

I bristle at calling White House-made photos propaganda. I was the lead picture editor for the White House Photo Office during the first four years of the George W. Bush administration. Eric Draper, President Bush’s chief photographer, made photos by the same standards as when he worked for the Associated Press, with added weight of documenting the whole of a presidency for history.

The process that governed releasing White House photos then was almost always propagandistic in that only positive photos of situations that the communications directors thought would advance the cause were released.

My successor said that was not the case during her tenure as the lead picture editor at the White House. Alice Gabriner edited photos for the first two years of the Obama administration, about 10,000 photos a week, and is now a picture editor for National Geographic magazine.

“I had very little constraint in what I was allowed to put out.” Gabriner said. She’d show pictures to her boss, Pete Souza, and the deputy press secretary and off they’d go. They were the same pictures she would have chosen when she worked for news magazines, including TIME, she said.

White House spokespeople call posting photos to social media a form of open government. And, to some degree, it is.

“Those visual press releases are only part of the story,” said Associated Press Director of Photography Santiago Lyon. I asked Lyon if he thinks the White House-released photos accurately depict life in the White House: “We wouldn’t know because we’re not allowed access into the events that are depicted.”

MaryAnne Golon, director of photography at the Washington Post and formerly at TIME and U.S. News and World Report, said that she was “appalled that it took six years for the journalism community to do something about this.”

The effort by 38 media entities to do something included a separate letter to APME and ASNE members encouraging them to stop publishing or airing White House-released photos. Some media have publicly agreed to do so – McClatchy newspapers, USA Today as of Dec. 2. The AP only distributes White House photos if they meet stringent criteria, Lyon said.

“It’s legitimate for them to push for more access, and in some cases I think their arguments are valid, and in some instances I think their arguments aren’t valid,” Souza said.

The same criticism about access, releases and usage were regularly volleyed at the Bush administration. It was fair criticism then, too. At least it appeared so from my perspective inside the White House Photo Office. (The Photo Office is staffed by government employees, usually five photographers, three or so picture editors, an archivist and an assistant. Most staffers since the Johnson administration have come to the Photo Office from media jobs. All positions, except the archivist and assistant, typically change with each administration.)

There’s hardly a rule that says whether to release a photo or not, nor to let one photographer in but not another.

We didn’t release photos of the President on 9/11 until months later but did release at least one image the night he initiated the war with Iraq. The thought behind releasing photos on 9/11 was that the nation’s attention shouldn’t be on the President, and that showing the setting when it was started was important in the moment.

Famed portrait photographer Arnold Newman called the office one day, asking to schedule a time to photograph President Bush. It wasn’t allowed, I was told, because there was not a clear and immediate benefit. Yet Annie Leibovitz and Gregory Heisler did photograph the president, because they were there to make pictures for publications.

Lyon said he’s complained to the press office for being allowed to photograph some world leaders with the president but not others.

I argued with the deputy and assistant press secretaries about the need to give photographers more access, seemingly to no apparent avail. Seldom would photographers get one-on-one time with the president and I gather that both kinds of access happen less often now. Gabriner said Souza also lobbied for press access.

The Bush Administration didn’t use social media to release photos during my time there, in part because it was new and in part because of a reluctance to put images out there, even on the White House web site. We would typically release one or two pictures a week, by email to media outlets throughout the world. Photos were usually of classified or restricted access situations related to 9/11 or one of the wars.

Other photos were also released, in response to specific requests from media. How many is hard to say but it’s definitely far fewer than the thousands out there of the current administration.

One photo released by Souza drew criticism for being altered. Souza blurred a classified document in a photo made in the Situation Room the night Osama Bin Laden was killed. We had to blur such documents related to the wars several times during the Bush administration.

The letter to Carney says the Obama administration restricts access to events that would have been considered public in previous administrations and then releases White House photos of those “private” events.

“I am very disappointed in President Obama for trying to limit press access,” said Lorraine Branham, dean of the S.I. Newhouse School of Public Communications at Syracuse University (where I now work as a chaired faculty member). “You cannot say it is private and then turn around and put out photos.

“Providing sanitized photos of the president and first family cannot take the place of real photojournalism and the journalistic decision-making involved in picture making and editing,” Branham said.

Doug Mills, who covers the White House for the New York Times, said, “The White House Photo Office has become the White House Wire Service.”

Golon, meanwhile, asks, “Where’s the journalism?”

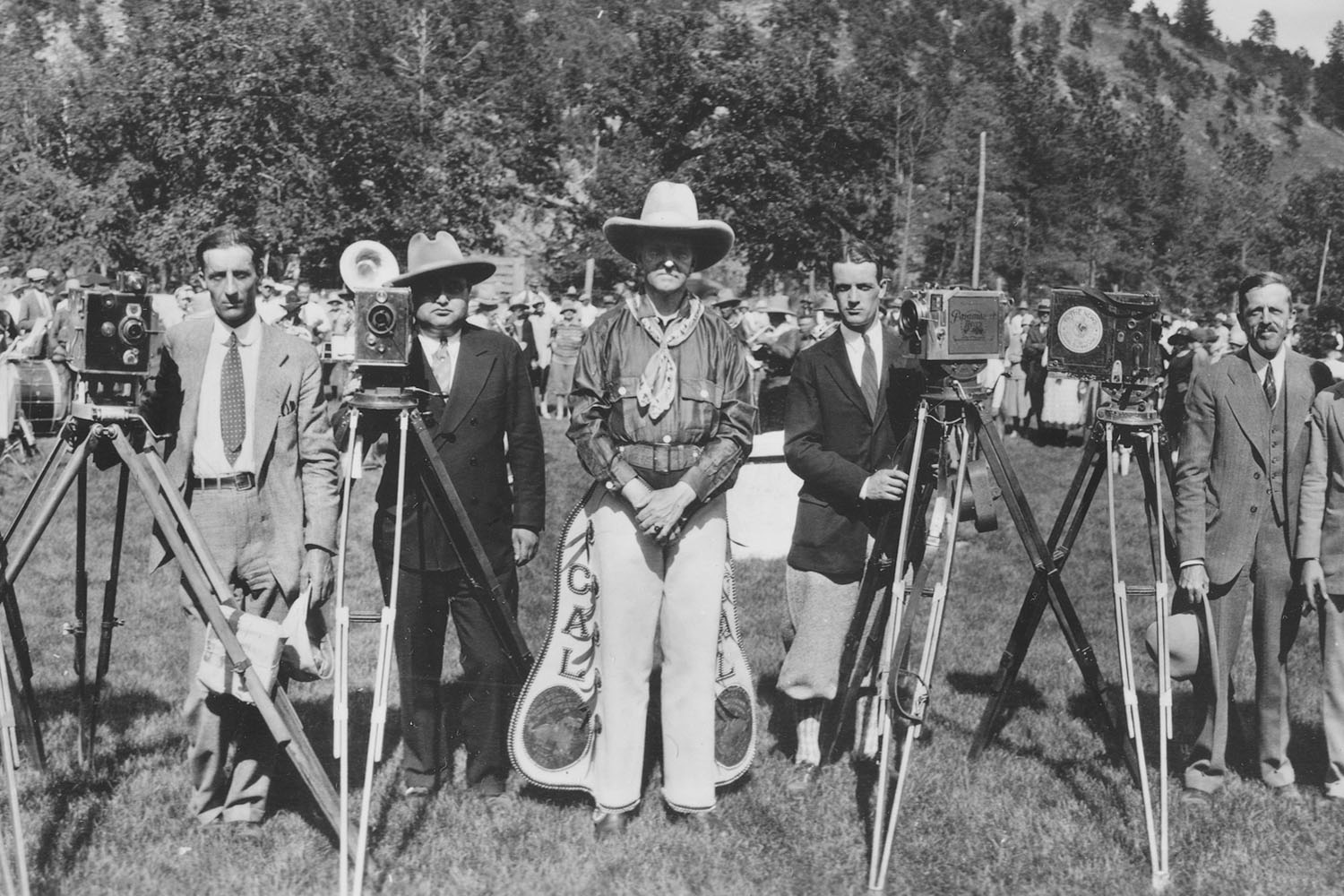

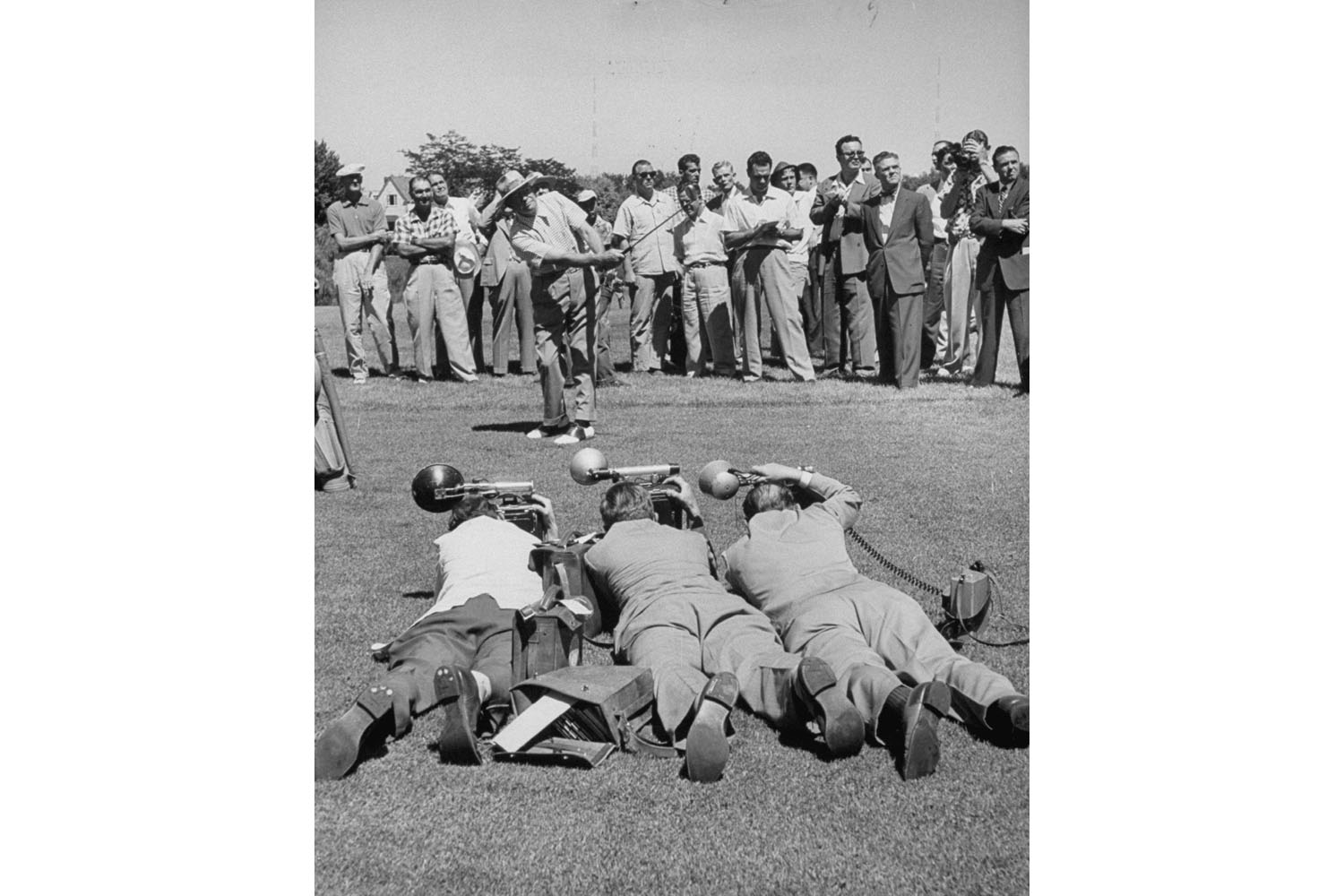

It would be convenient to think that there has been a progression of greater restriction of access with each president. The truth is more complex and more reliant on whether each president wants to be photographed.

Some presidential administrations made rules to govern what couldn’t be photographed: Photographers were prohibited from showing FDR in a wheelchair and from showing President Kennedy in glasses. That was then.

More than one photographer said that President Obama appears to enjoy the presence of photographers and understands that there is value in strong photography, but this wasn’t always the case. He did not hire a professional photographer to cover his first campaign for president, instead tapping a trusted staffer to snap pictures.

Photographers said they have noticed a positive evolution in how the president responds to being photographed. So one has to wonder why access isn’t better. A query to the Press Office didn’t provide an answer.

“I don’t see what they’re afraid of. They’re gorgeous people, everybody wants to see them (the first family),” Golon said.

Gabriner said her impression was that “this White House feels the press doesn’t cover them fairly, or accurately, so they’re putting out their own photos.”

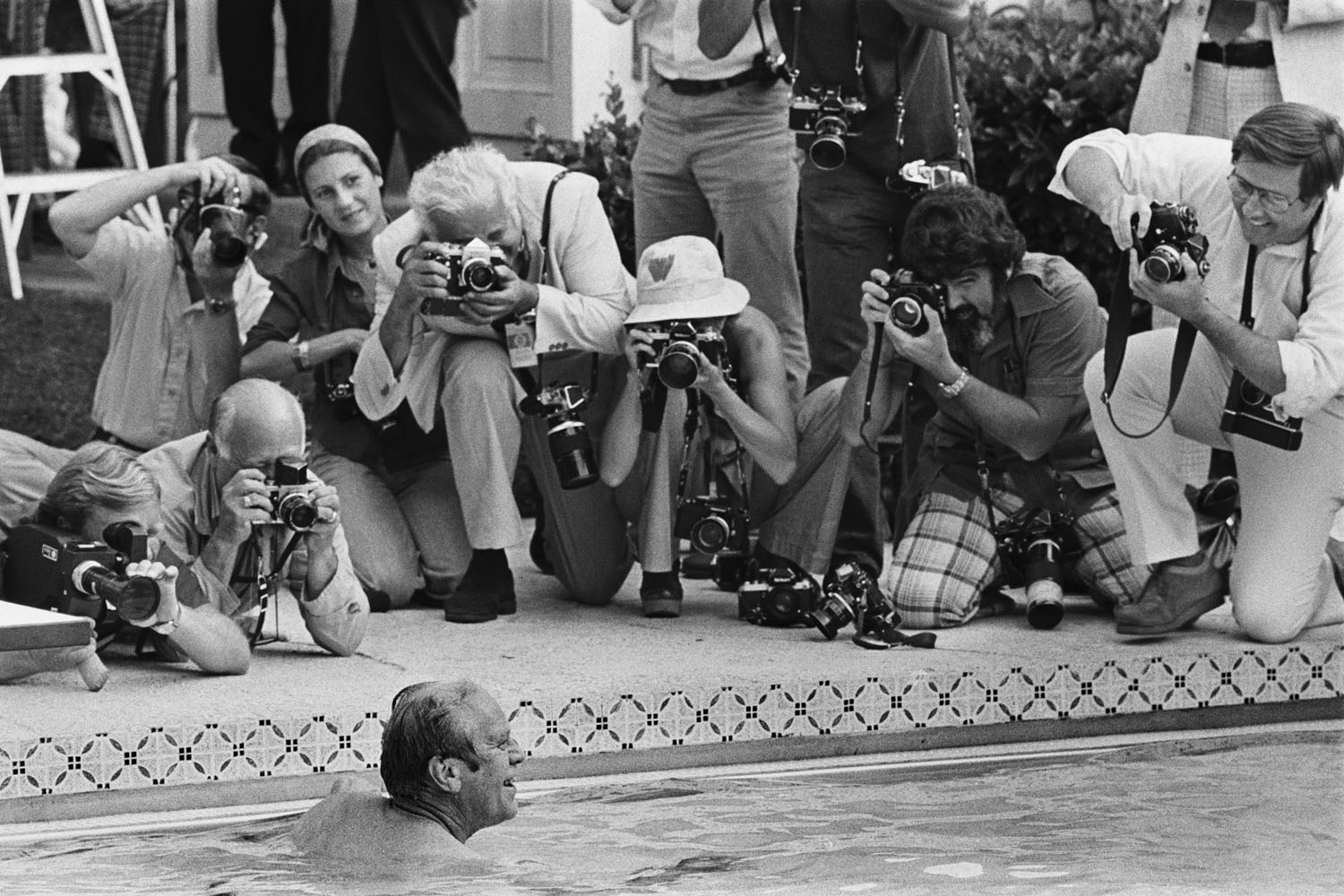

Diana Walker photographed several presidents for TIME. She described photographing President Clinton: “We were probably a pain in the neck to have around all the time. But he seemed to enjoy pictures.”

The last president Walker photographed was then President-elect Bush. “Spending a day or two with him, I realized he was not comfortable with behind the scenes photos, with me hanging around him.” After President Bush took office, “I thought my requests would fall on deaf ears and that’s what happened.”

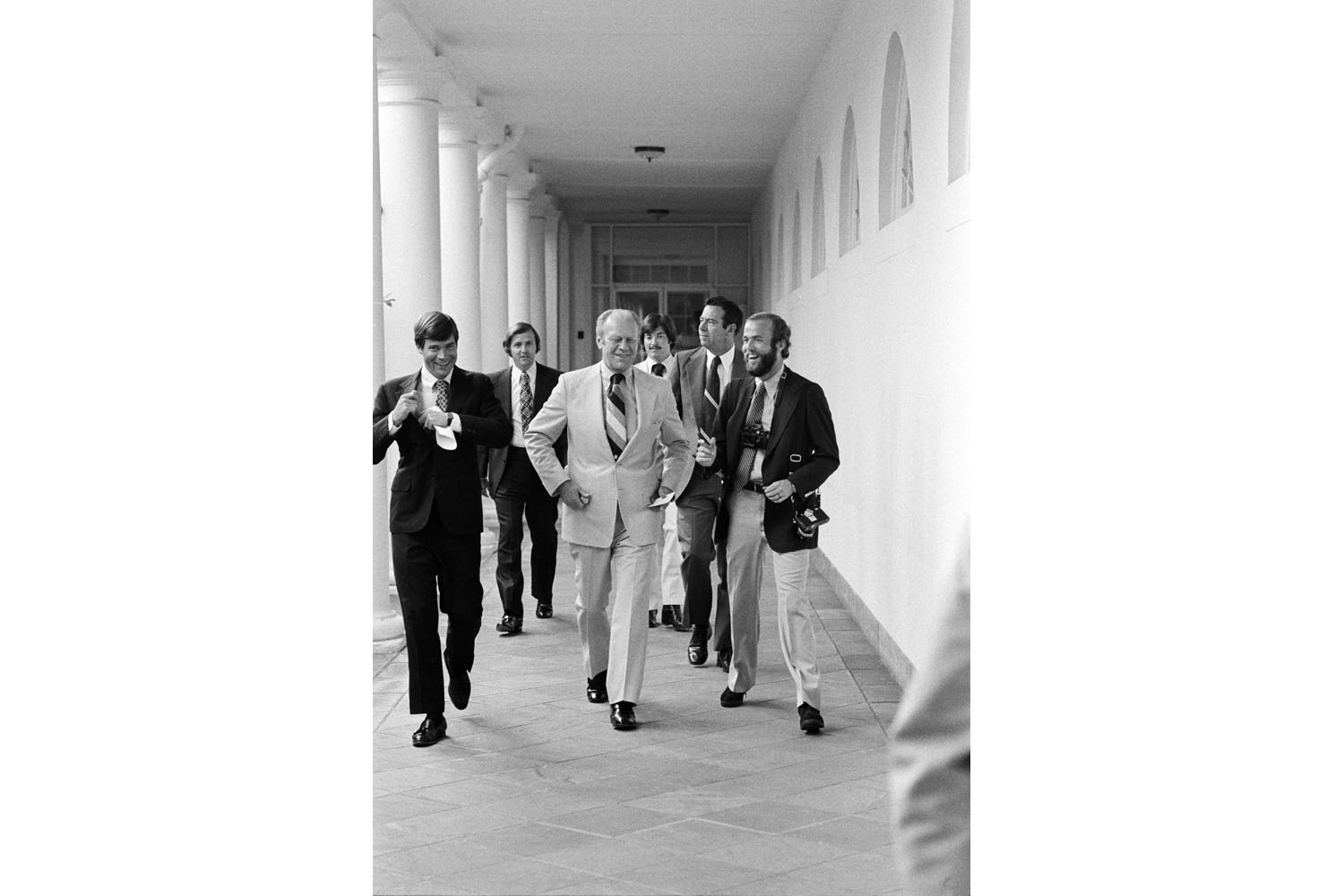

The Clinton and Ford administrations stand out as allowing more media photographers to make pictures of the president one on one. That fact plays out in the number of books produced by photographers about those administrations, something that seems unlikely of the current administration, for lack of images.

David Hume Kennerly was President Ford’s photographer and an advocate for media access. He said he’d just ask President Ford if he wanted to let a photographer make pictures as he went about his presidential duties. About 60 photographers got to do so, one-on-one, during his two and a half years, Kennerly said.

“Why not let in photographers as often as you can?” Kennerly said. “I just don’t see the down side.”

But he doesn’t see getting the media access as the president’s photographer’s responsibility. “Pete Souza does a good job as a documentary photographer, a historian. That’s how he’ll be judged.”

Lyon agreed, “This is not personal. The president’s official photographer is doing his job.”

Christopher Morris, of VII Photo and a TIME contract photographer, photographed the Bush years and the beginning of the Obama years for TIME. His idea of how to solve the access issue: “Something needs to be structured where on a rotating basis one tight pool photographer should be given special access for the day, basically to shadow the White House chief photographer, for let’s say 50 percent of the day or as the President’s schedule allows.”

Makes sense to me. A similar arrangement exists for televised presidential speeches so the model is in place within the White House.

Whether photographers or the companies they work for would share images, whether the administration would allow that frequency of access and if the Chief Photographer would be open to it, however, are big questions.

We all lose now, and history loses in the long run if there isn’t a resolution.

In Walker’s time, there were more press photographers covering the White House. All three weekly news magazines staffed the White House daily — something they no longer do. It’s an expensive undertaking that with diminishing access is ever more difficult for media outlets to justify.

“You’re just killing off photojournalism a little more every day,” Crowley said.

And without a trust that is earned only from being at the White House most days, the chances of getting anything other than restricted pool access diminish.

I asked everyone I talked to: What does all this matter? Why is it important that photos of a president come from more than one primary, government-funded source?

The media’s letter to Carney cites the First Amendment’s protection of “the public and the press from abridgment of their rights of access to information about the operation of their government.” That’s a highfalutin way of saying that we deserve an unbiased, unfiltered photographic impression of our President’s term.

As Diana Walker put it: “I thought it was important to show the smallest detail. My theory was that I was there for the people who read TIME magazine.”

White House Photo Office photos remain largely inaccessible for decades after an administration leaves office. The photos are technically public, under the auspices of the National Archive, but they are tightly controlled by descendants of the administration.

For now, we’re largely limited to seeing a flow of pictures from the White House to social media. In the future, if we are to see the life of the White House beyond the antiseptic version, it has to come from the media.

Mike Davis holds the Alexia Tsairis Chair for Documentary Photography at S.I. Newhouse School of Public Communications at Syracuse University. He has been a picture editor and visual leader at the White House, National Geographic magazine and several U.S. newspapers. Among the books he has edited is Eric Draper’s “Front Row Seat, A Photographic Portrait of the Presidency of George W. Bush.”

![Dwight D. Eisenhower [Misc.] White House Photographers Through The Years](https://api.time.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/50653806.jpg?quality=75&w=2400)

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Inside Elon Musk’s War on Washington

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Cecily Strong on Goober the Clown

- Column: The Rise of America’s Broligarchy

Contact us at letters@time.com