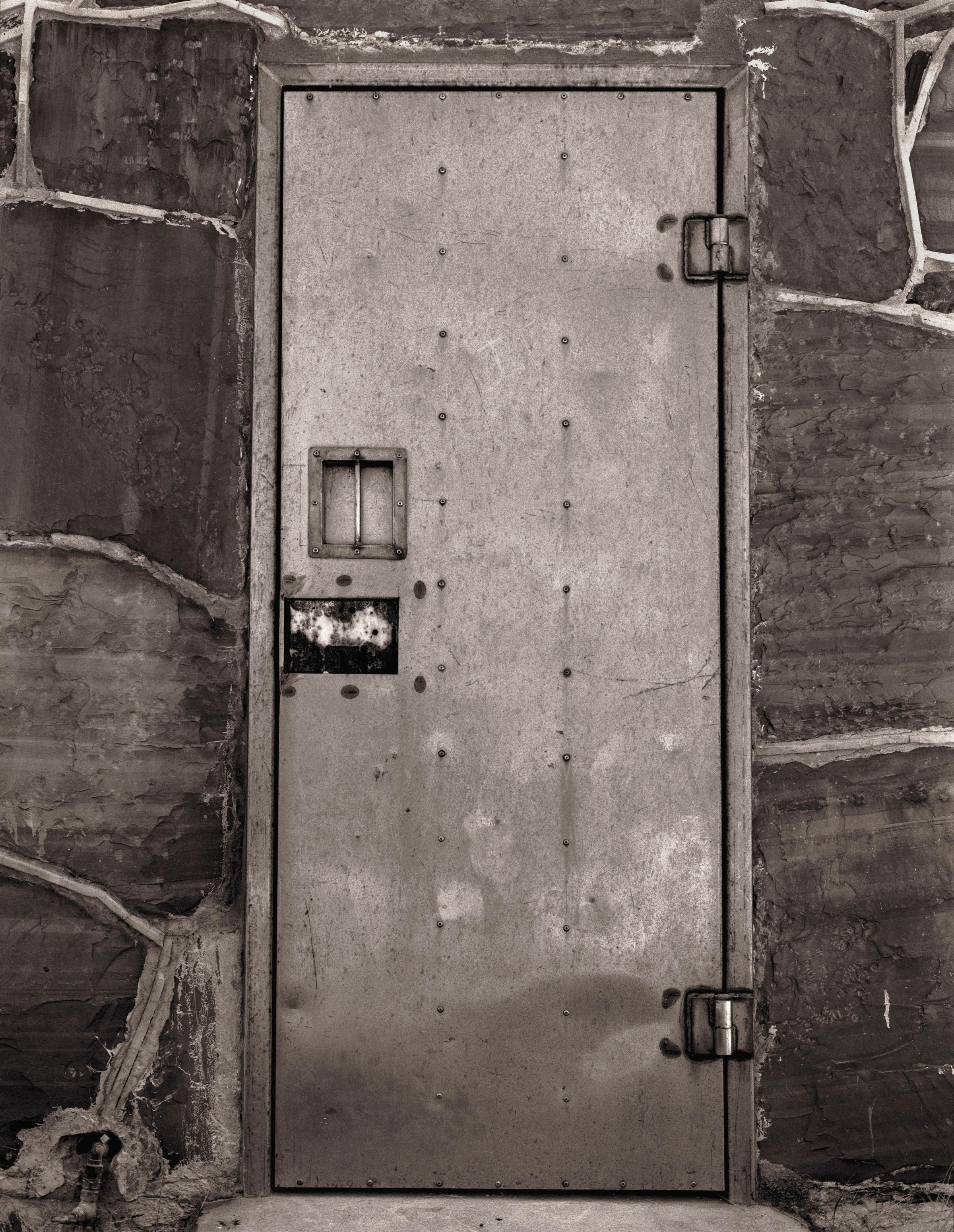

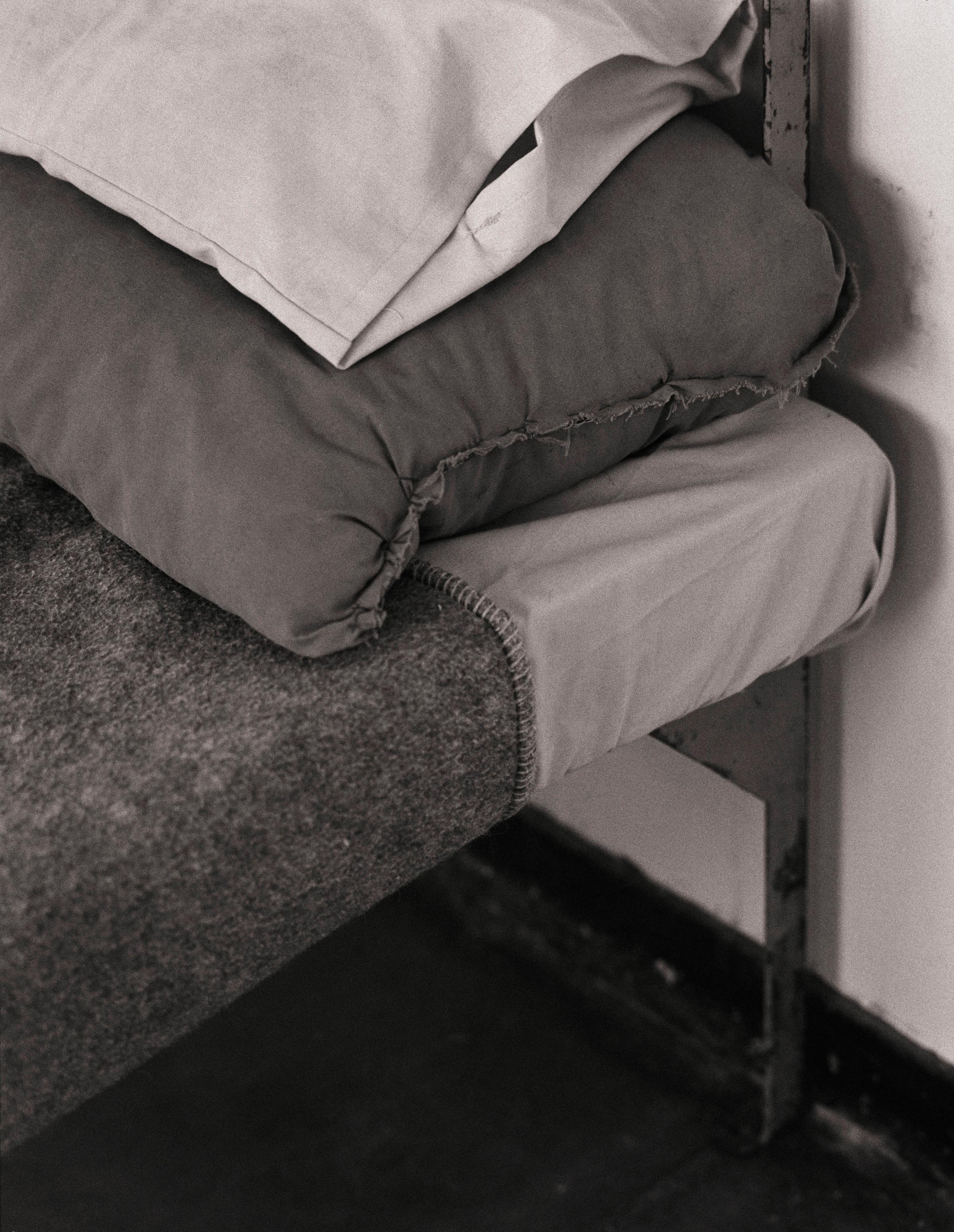

Relentlessly pounded by the angry surf and chilled by the icy winds of the south Atlantic, Robben Island is the unlikely cradle of South African democracy. That wasn’t exactly what the Dutch and British empires had in mind when they began, from the 17th century, using the two-square mile rocky outcrop four miles off Cape Town as a prison. Being sent to live out their day on Robben Island was the fate of those who dared resist the incursion of European settlers. And the white-minority regime that inherited the reins of colonial power maintained that tradition.

Nelson Mandela, leader of the armed wing of the African National Congress spent 18 of his 27 years in prison there, and emerged to lead all South Africans, black and white, in a process of democratic reconciliation that became a global icon of humanity’s ability to transcend racism. But three centuries before Mandela broke rocks in its dusty quarry, the Island (as it was known in South Africa) had held the indigenous leader Autshumao, known to the Dutch as “Harry the Beachcomber”, mutinous slaves brought to the Cape from the Dutch East Indies, and the Xhosa insurgent leader Makana who had risen against the British in 1819.

But it was Mandela and his cohort who put the Island on the international map. Having taken up arms against the apartheid regime when all channels of peaceful protest were closed by violent repression, their insurgency was crushed, and like Autshumao and Makana before them, they were sent to rot on the Island, their fate intended as an object lesson to all who would dare challenge the authority of the white man.

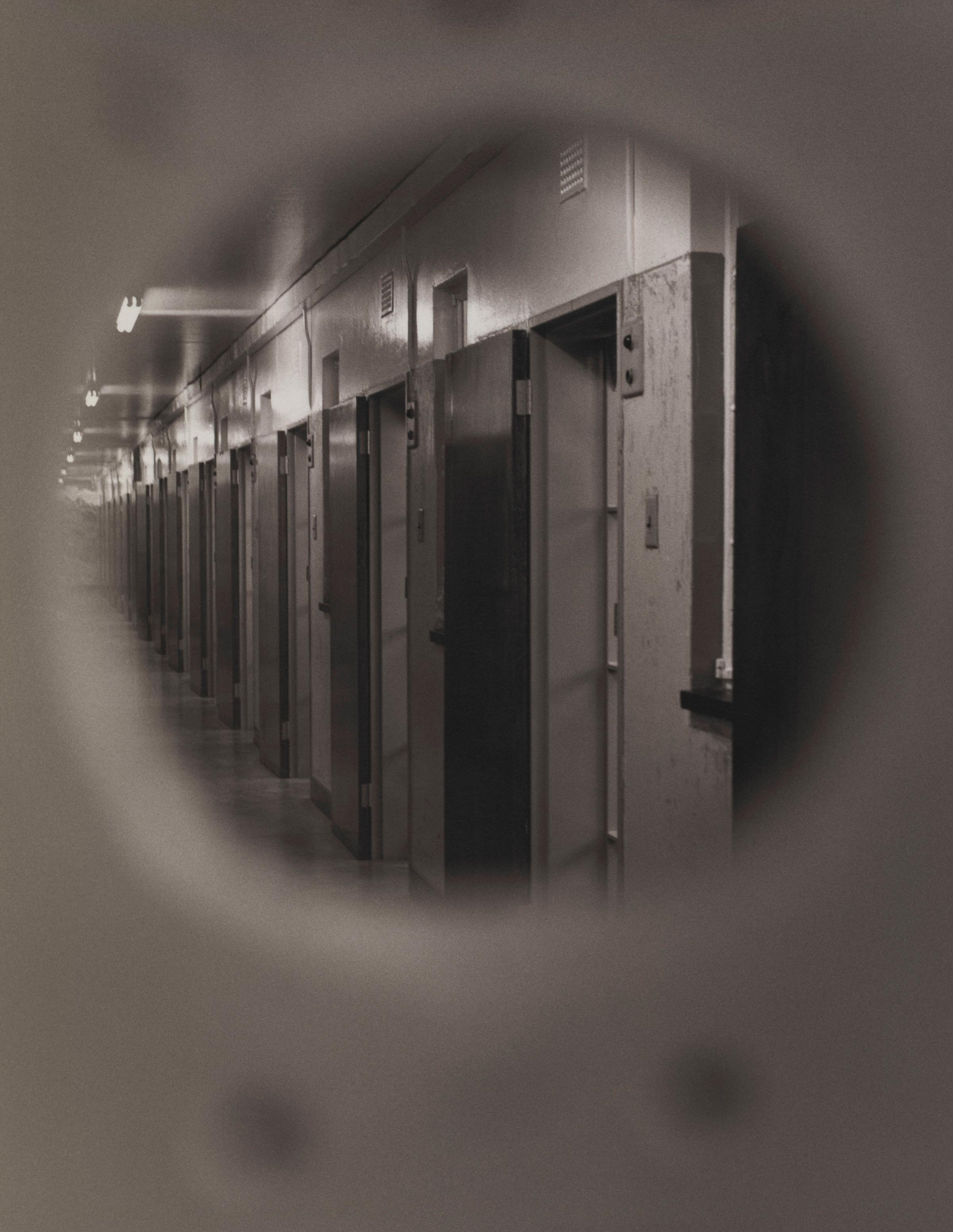

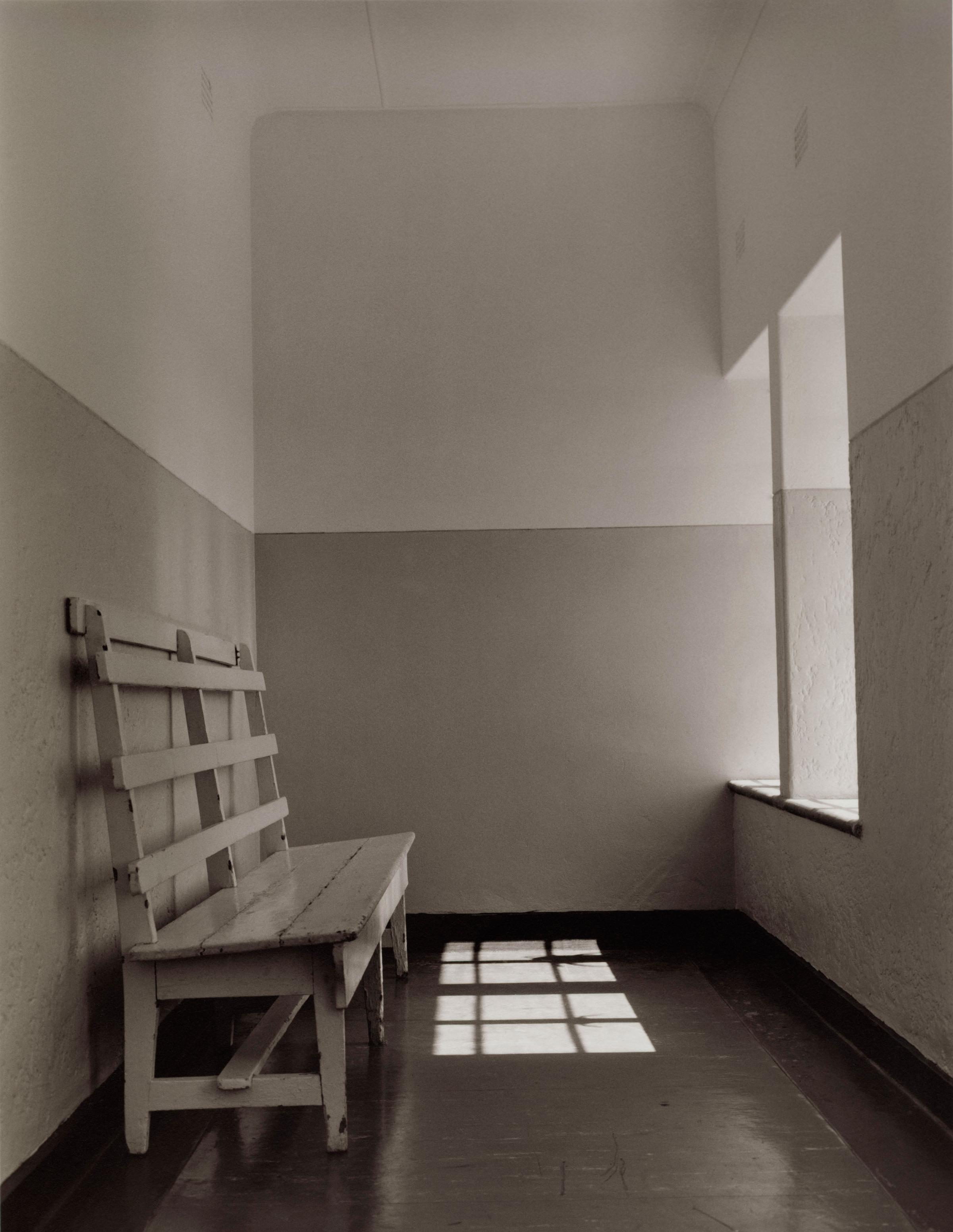

Things didn’t work out that way. Despite the best efforts of the prison authorities to break their spirit, the prisoners organized themselves and steadily expanded their control of the institution’s culture. The Island became known as “the university of the struggle,” each new wave of young rebels brought to the prison falling under the tutelage of Mandela’s generation, leaving the prison to rejoin the fight with the equivalent of a revolutionary MBA.

And what Mandela taught them was the ANC’s core belief that, “South Africa belongs to all who live in it, black and white, and no government can justly claim authority unless it is based on the will of all the people.” Many young convicts came to the Island hating white people, having watched their unarmed peers cut down in the streets by the apartheid security forces; Mandela and his comrades, through patient political education on the ethics and mechanics of political change, brought them round to a vision of a common future for all South Africans.

And it was during his years on the Island that Mandela closely studied the psyche of his Afrikaner jailers, his encounters with their humanity and fears profoundly shaping his negotiations with the minority regime that enabled a peaceful transition to majority rule.

Robben Island remains a shrine to South Africa’s unique achievement in liberation and reconciliation, revered precisely because it failed to serve its purpose.

Koto Bolofo was born in South Africa and raised in Great Britain. He has made photographs and short films for clients such as Vogue, Vanity Fair and GQ. More of his work can be seen here.

Tony Karon served as senior editor at TIME from 1997 – 2013, where he covered international conflicts in the Middle East, Asia, and the Balkans.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com