My uncle Frank Silano died from complications of AIDS in December 1989. My family rarely spoke of him. He was a mystery to me. The few things I did know were generalities: he was gay, lived in New York and died young. I always wanted to know more, but no one could tell me anything else. It took me a quarter-century to begin unraveling who he was.

It started with a Polaroid I received when my parents separated. It was the first photograph I had ever seen of my uncle; I had never seen his face before. In the picture he seemed so serious, wearing a coat and tie with the camera’s flash reflected in a nearby mirror. It looked like one of those snapshots a family member might take when you’re on your way out the door after a holiday dinner or gathering. I studied that Polaroid thinking it might be a clue to who my uncle was. I figured if I could know him, I might have a better sense of myself. Around this time I had a major falling out with my father over being gay. The experience made me feel closer to this outsider that the family forgot.

My attempts to find more photographs and stories of my uncle yielded no results. It was incredibly frustrating and in many ways I felt defeated. I had intended to make a project about him, but with virtually no source material or support I had to put my focus elsewhere. If I couldn’t make a portrait of Frank Silano I decided I would make one about other gay men who died as a result of the AIDS epidemic.

I took that Polaroid of my uncle and I hung it up on my studio wall. It would serve as motivation and a constant reminder of Frank and of how lucky I am to be gay and alive today.

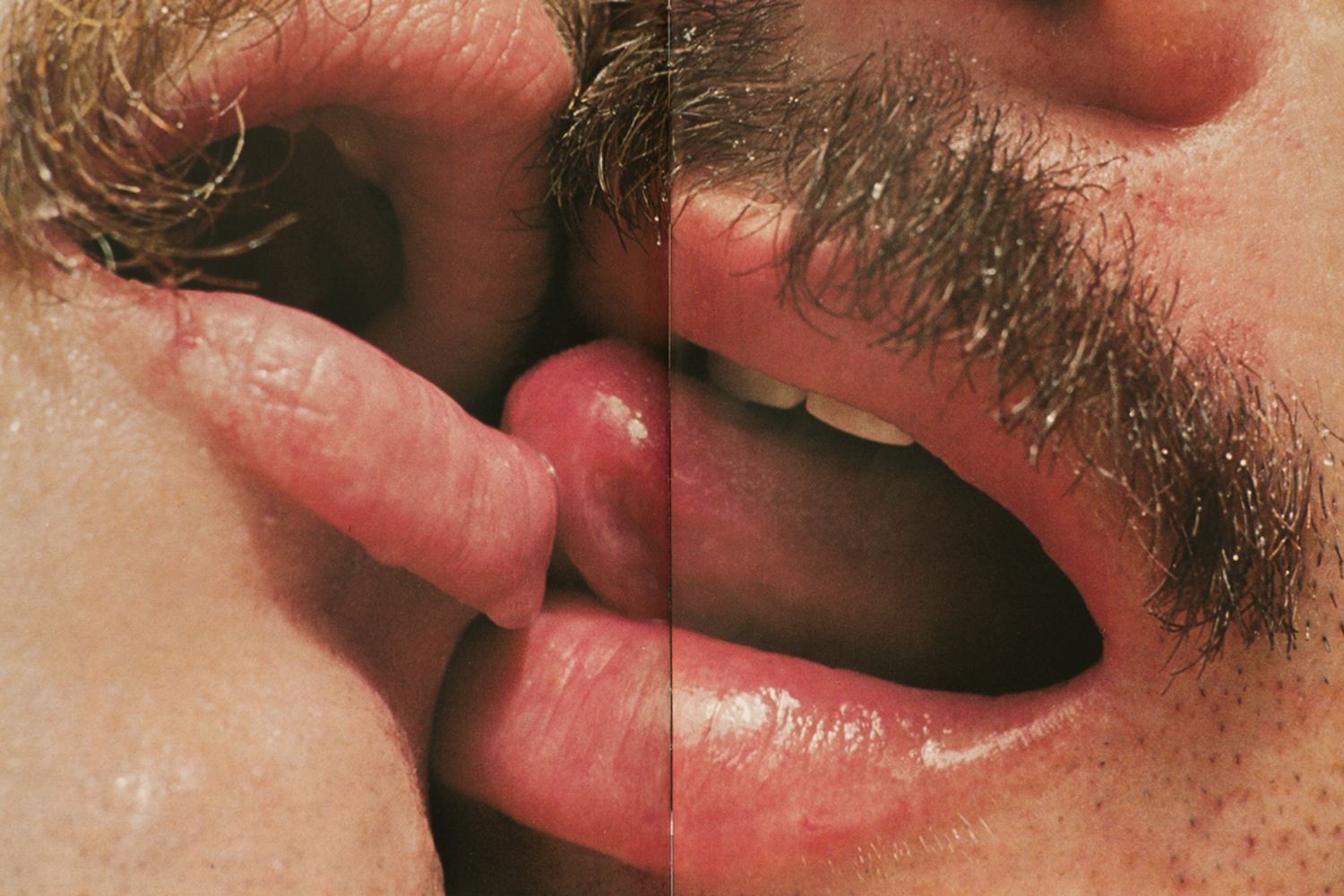

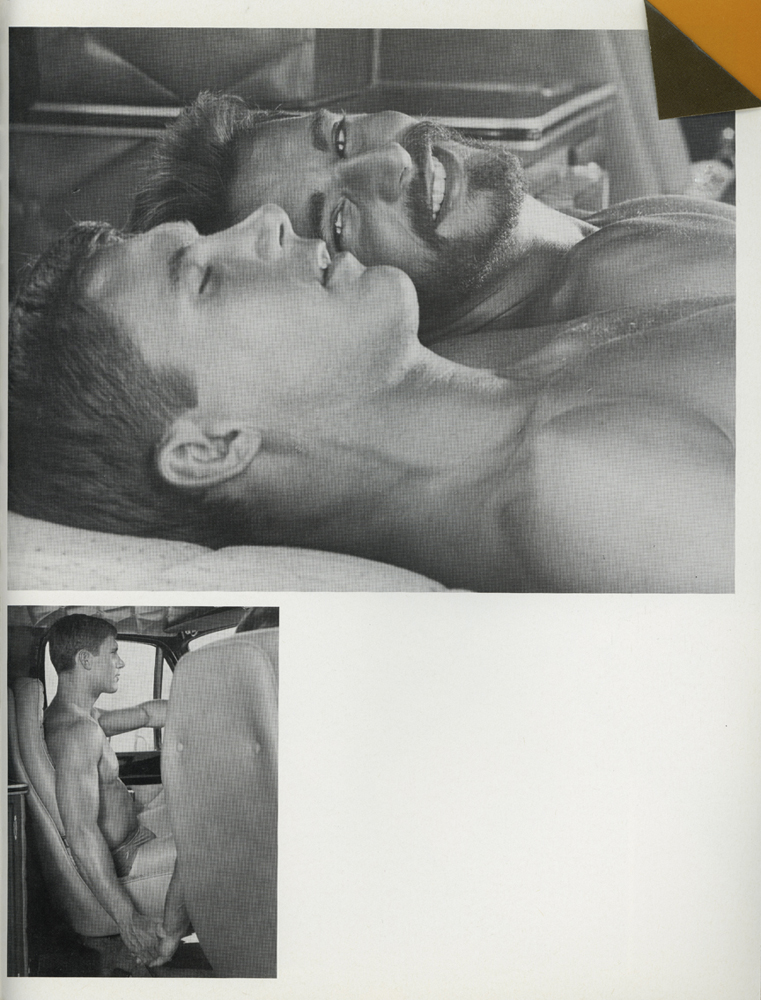

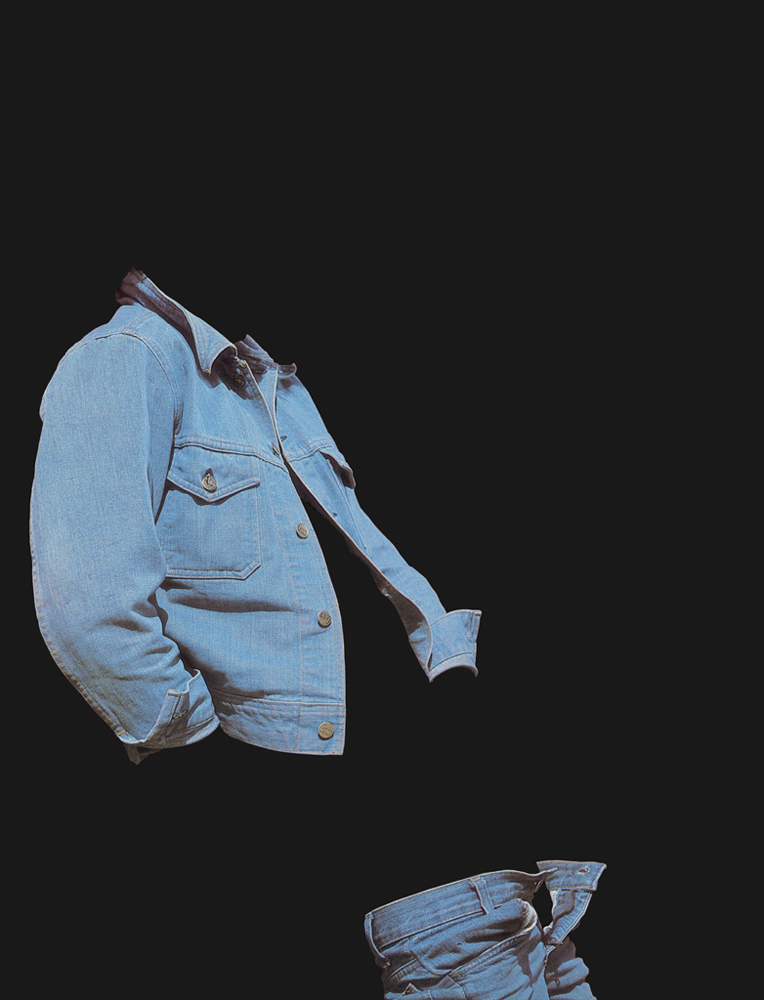

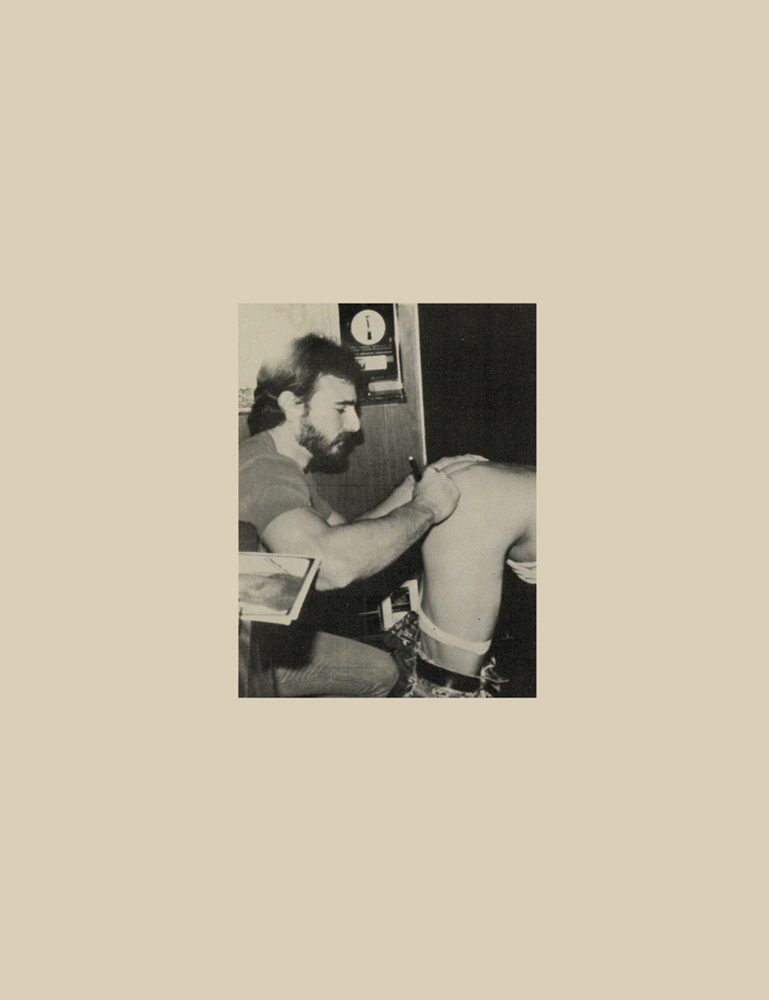

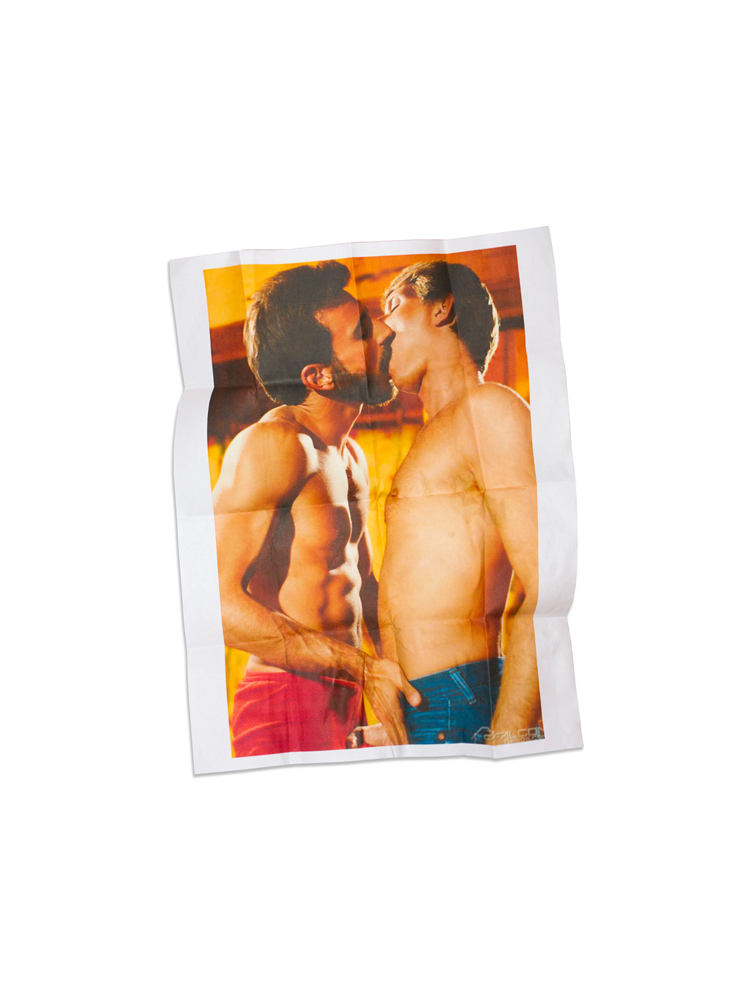

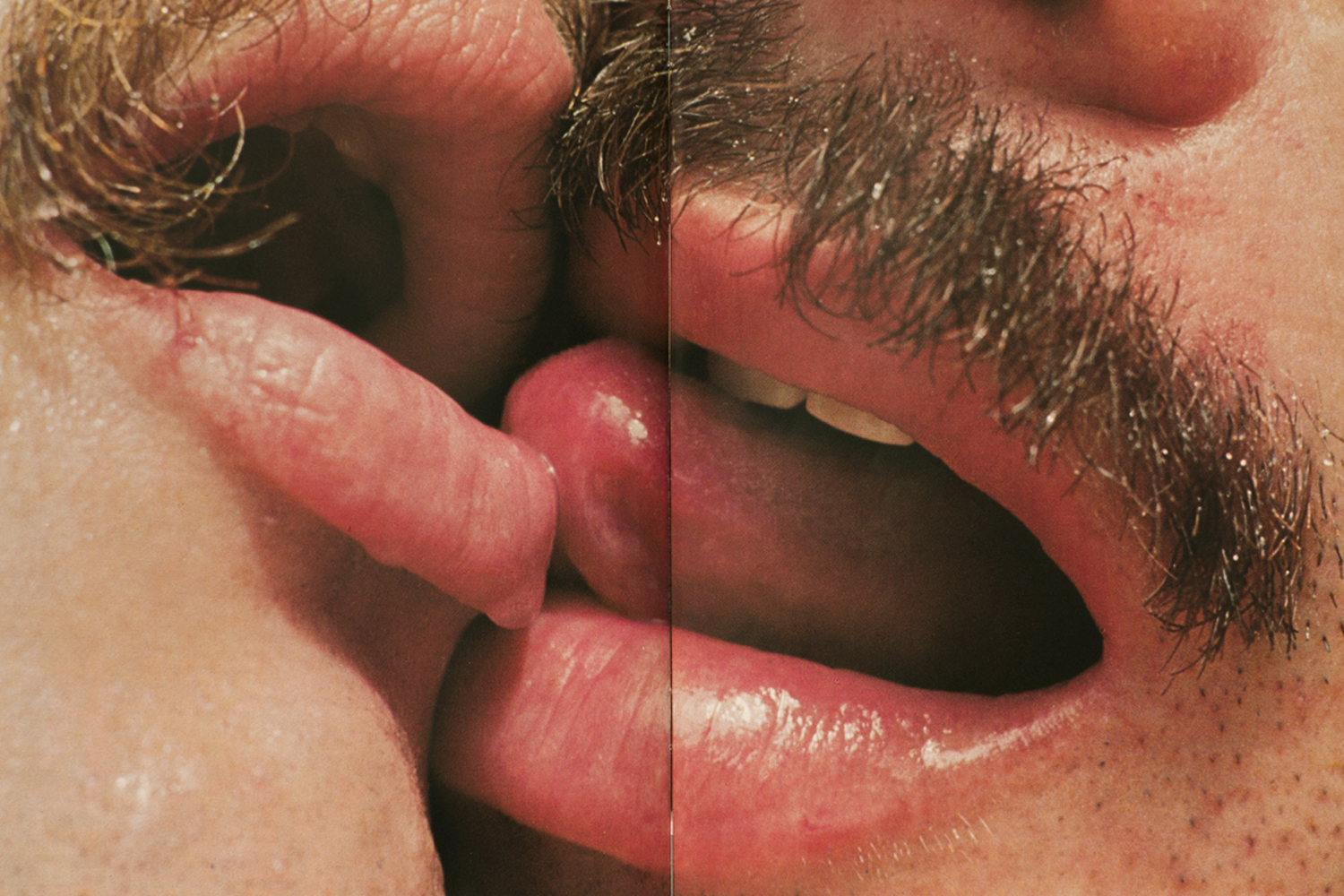

In 2010 I began to research the history of the LGBTQ community. I started reading about the Stone Wall Riots and the gay rights movement. Fascinated with the sexual liberation and visibility of gay men after 1969, I watched probably every documentary I could about the AIDS epidemic. I collected ephemera and vintage pornography. I found myself drawn to depictions of hyper-masculinity that seemed at odds with the conventional views of gay men.

I began re-contextualizing images from old magazines, found photographs and negatives, in part as a way of breathing life into the past. When I couldn’t find an image that represented my own vision, I would stage a photograph. These ideas became the basis for my project, Where the Boys Are, a series highlighting the innocence and naivety of these men as well as foreshadowing what came later.

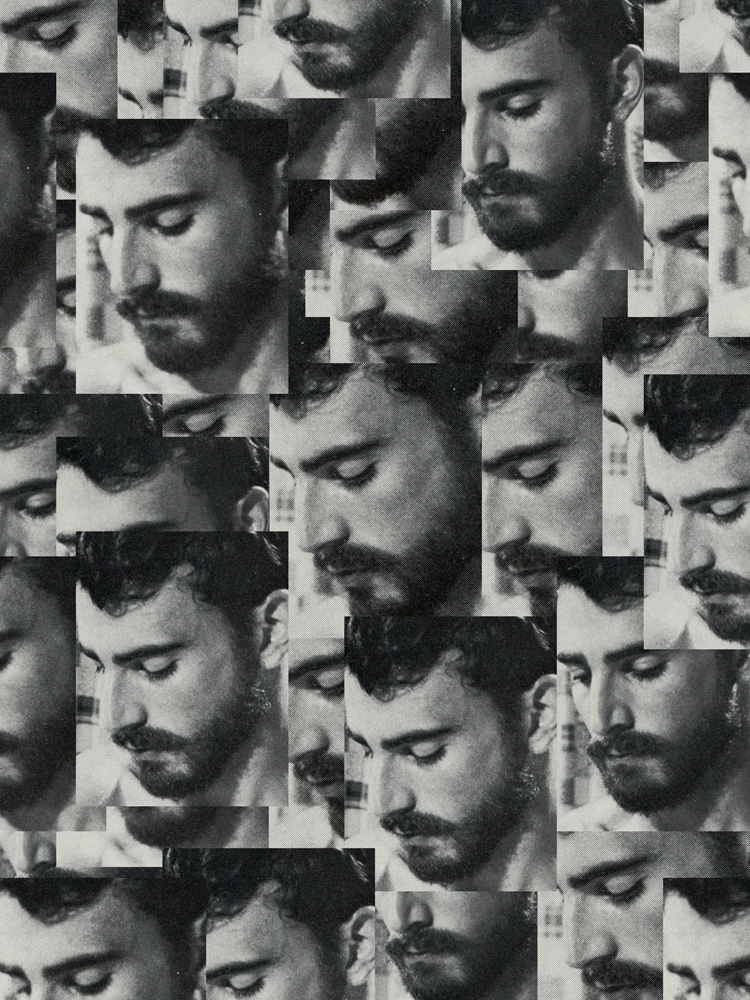

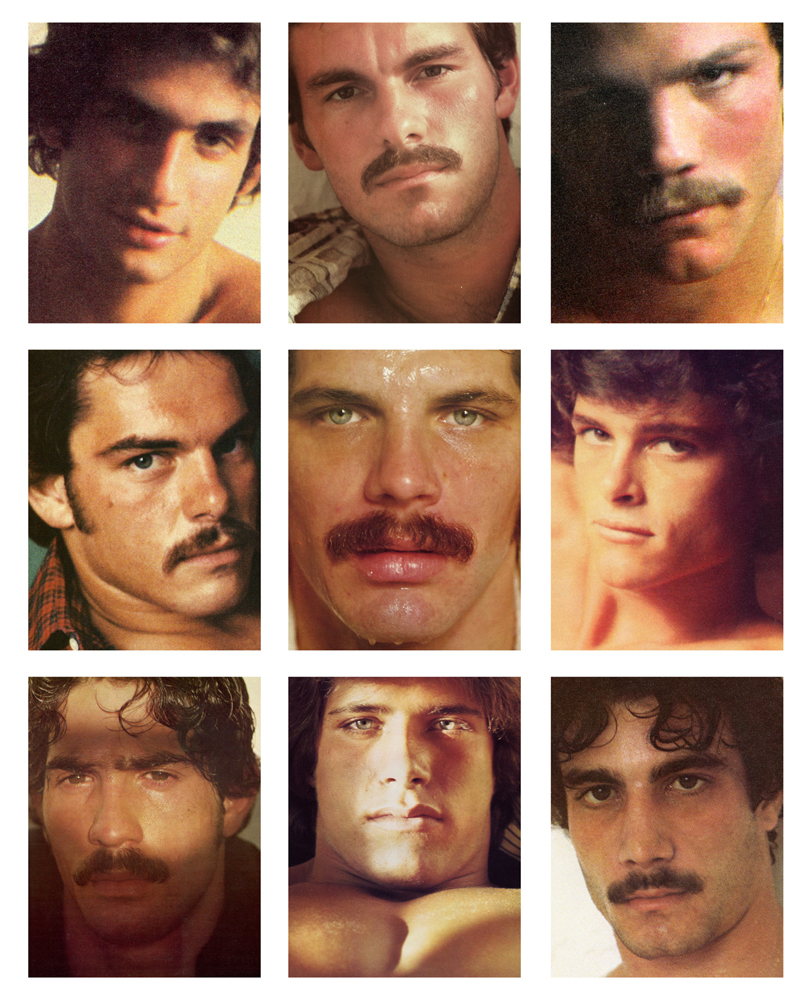

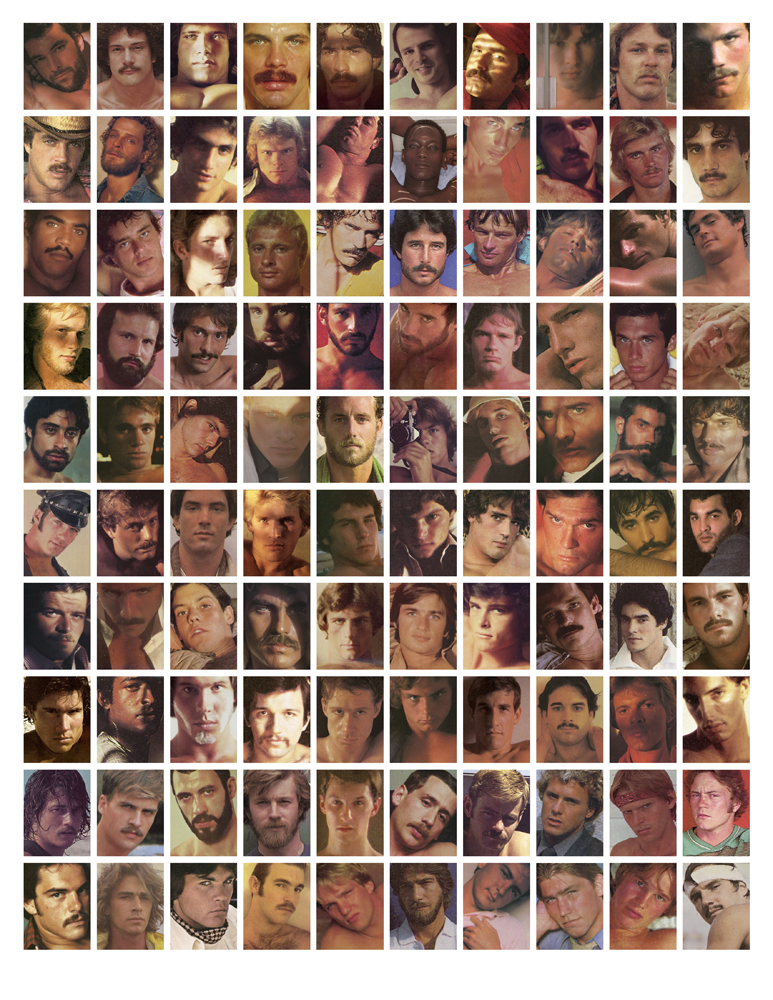

In the summer of 2012 I received an Aaron Siskind Fellowship for this body of work and used the funds to pursue similar ideas. I specifically focused on creating a photo installation titled Pages of a Blueboy Magazine. Consisting of one hundred cropped headshots of male centerfolds, I chose models from issues that ranged between the years 1974 and 1983 (the year Blueboy published their first article on AIDS). Each man’s gaze is meant to draw the viewer in and contemplate the mortality of not only the model but also the men who originally consumed the imagery. The work had its debut at the Bronx Museum of the Art’s 2nd AIM Biennial in June 2013.

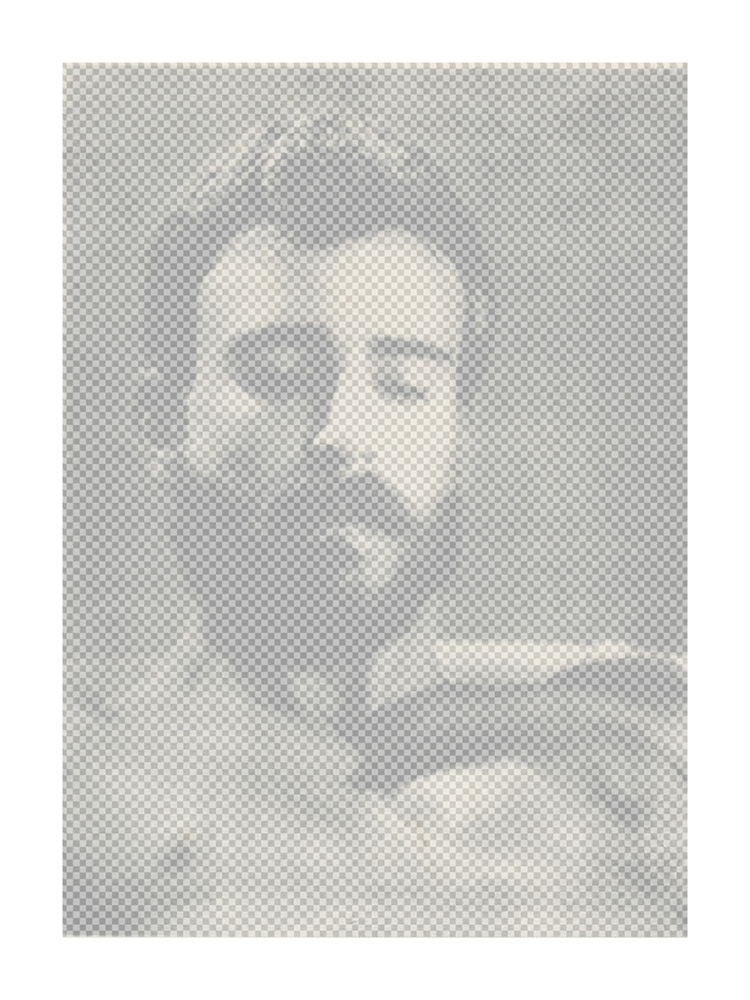

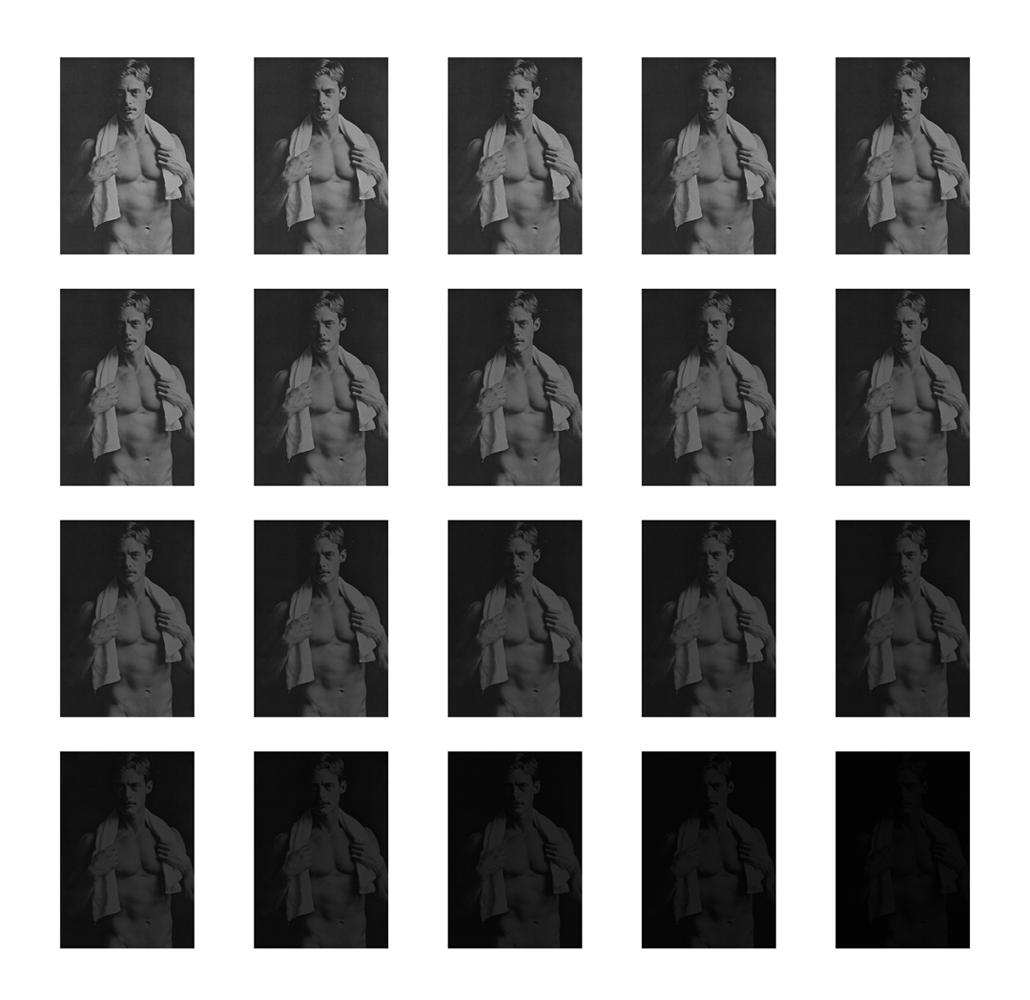

My most recent project, Male Fantasy Icon, furthers the themes I’ve explored in the past. By creating imagery with Al Parker, one of the most famous gay porn stars of the 1970s, I’ve produced photographs that memorialize and draw attention to a lost generation of gay men. The process of making these new pictures and reworking images from the past has allowed me to catalog and emphasize a neglected history, one that is imbued with my own fantasies of a place and time I feel I know, but that I never lived through.

In creating all of these photographs, I have gained a better understanding of what life might have been like for my uncle. I’ll never hear his stories first-hand, but something has nevertheless been passed on. Sometimes I like to think that he’s guiding me through my own work. When I’m lost for an idea in the studio, I’ll look up at that old Polaroid and I’ll remember how my journey began.

Pacifico Silano is a photographer based in Brooklyn, N.Y.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com