It’s raining! Suddenly, drops of water drip through the beautiful 19th century Beaux-Arts iron and glass vaults of the Grand Palais where 136 galleries and publishers are hosted for the 17th annual celebration of Paris Photo, headed by Julien Frydman. Gallery owners scramble to cover the photographs with plastic sheets…and then, the sun shines again.

The Protest Book 1956-2013 exhibit, curated from Martin Parr’s collection, ranges from anonymous or self-published books and brochures to classics by famous photographers such as Philip Jones-Griffiths’s Vietnam Inc., Peter Magubane’s The Fruit of Fear or Richard Avedon’s Nothing Personal. The issues concern civil rights, nuclear arms, gay and women issues, African-American civil rights, the Arab Spring… My only regret is that very few of the book spreads are visible in the vitrines.

At Jérôme Poggi gallery, the focus is on several series by Sophie Ristelhueber, ranging from the devastated facades of Beirut and Armenia to the overviews of the Kuwait desert. War and suffering are never shown directly but through their reflections in landscape or in scarred bodies such as those of the striking series EveryOne. At Bruce Silverstein Gallery, I discovered some unknown (by me), lush color work of wooden walls with geometric motifs in a square format by Aaron Siskind, made in Bahia in the 1980s. Galerie Polka had series by war photographer Stanley Greene, prints from Salgado’s recent work Genesis, and striking, enlarged contact sheets of Daido Moriyama’s Labyrinth, that he created by mixing together negatives from disparate rolls of films, regardless of chronology or provenance. It is an immersion into over fifty years of images.

At Galerie Vu, another discovery was Le Temps d’Avant (1966-1969), square color images that Bernard Faucon did when he was still a teenager, before he became known for his staged photographs of mannequins. Van der Elsken series on love in St Germain des Prés (1961) and Anders Petersen’s Café Lehmitz complete this flashback into the sixties. At Howard Greenberg’s gallery, the choice is extraordinary, from Roy deCarava’s still life to Gordon Parks Harlem portrait, and prints of Kertesz, Brassai, Gjon Mili, Saul Leiter, Bill Brandt…

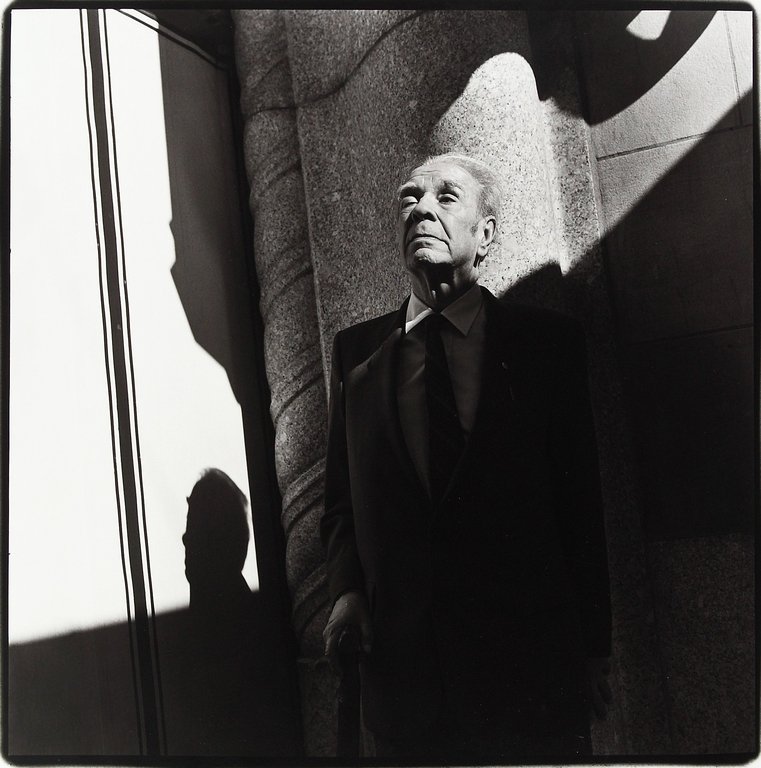

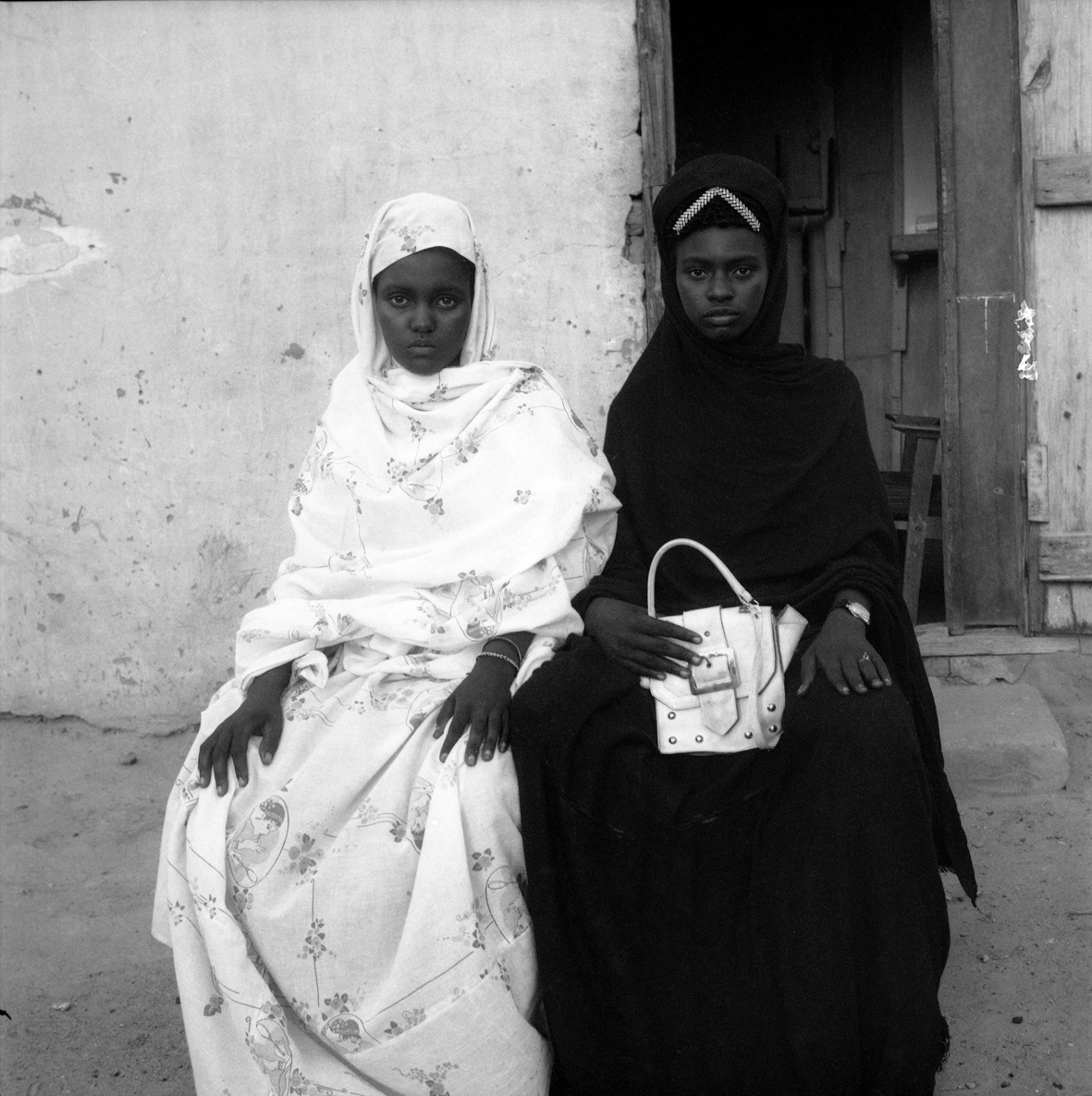

I especially enjoyed Vivian Maier’s self-portraits: she was a nanny who worked in Chicago from the 1950s into the late 1990s and whose beautiful body of work was only discovered by chance after her death in a thrift auction house. André Magnin gallery specializes in African photography, a field long ignored, with photographs by well-known artists such as studio portraitist Malik Sidibé but also unknowns such as Seydou Keyne or J. Dokhai Ojeikere, who photographed elaborate African hairstyles.

The Daniel Blau gallery made an amazing discovery in the archives of a photo agency that was closing: to celebrate Robert Capa’s 100th anniversary (he was born in 1913), they exhibit 65 prints that he made on European war fronts in Italy, France and Russia. An entire wall of mostly unknown photographs, shot in Rolleiflex and 35mm, to discover.

Beyond Paris Photo, the feast has spilled all over town with fifty other photography shows, most of them lasting into December and the new year. The Brassai retrospective at the Hôtel de Ville is one of the best. Apart from his famous images from the book Paris by Night, his studies of Picasso in his studio and his café shots, I was especially drawn to a poetic, mysterious set of images taken at Les Halles market: a black man carrying a meat carcass across his shoulders, like Christ with his cross. A new gallery, Le Comptoir Général, also home to a bar and a restaurant, specializes in showing unknown work made in 1960s African photography studios. Their current show of Oumar Ly is a series of portraits of villagers clothed in their Sunday best, against a makeshift painted background. The work is strong and fresh.

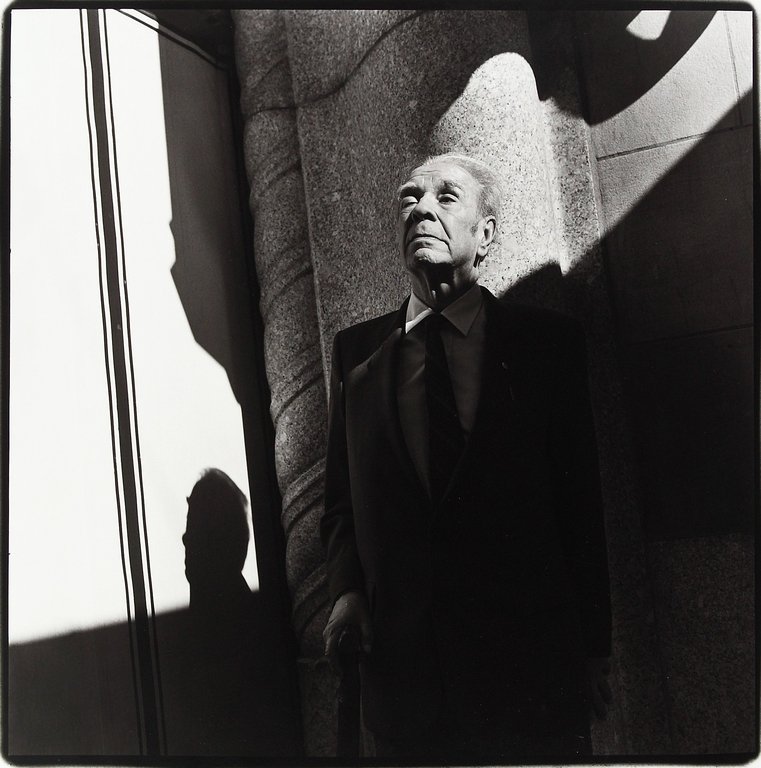

Marc Cohen’s Dark Knees at Le Bal is intriguing, stark and sophisticated, capturing fragmented slices of life from his hometown Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania. It is a world askew, vibrating. Sylvia Plachy’s nostalgic and ironic portraits at Espaces 54 seem to capture their subjects’souls. Marguerite Duras’s serious gaze, Jorge Luis Borges leaning on a wall next to his shadow, Adrian Brody as a child, blowing a chewing gum that veils his face…

Coinciding with Paris Photo’s opening, the daily Libération published this Thursday an entire issue where photographs are but empty white rectangles, with only copyrights and captions. The editor explains that while the photography market is blossoming, magazines are dwindling and the fate of press photographers, war photographers in particular, remains uncertain, dangerous and poorly paid. Set in Paris’s current flood of images, this homage in absentia seems to make photography all the more visible.

Carole Naggar is a photo historian, poet and regular contributor to LightBox. She recently wrote on the work of Swedish photographer Anders Petersen.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- How Far Trump Would Go

- Why Maternity Care Is Underpaid

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- Saving Seconds Is Better Than Hours

- Why Your Breakfast Should Start with a Vegetable

- Welcome to the Golden Age of Ryan Gosling

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com