While very well-known in Europe, where his first book, Café Lehmitz (1978), is considered seminal in the history of European photography, Swedish photographer Anders Petersen has not yet found a similar level of recognition in the United States.

Our conversation coincides with his upcoming, 320-picture retrospective at the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris.

In 1958, when he was fourteen, Petersen’s family moved from Stockholm, where he was born, to Karlstadt in Värmland, “in the middle of nature and all the fairy tales. It was a lonely and confusing time,” he told me, “full of memories and a warm confidence, close to the lakes and forests. I wasn’t interested in school, but I liked adventures. Inspired by artists like Karin Bodland, Lars Sjögren and Göran Tunström, I liked to paint and write short stories. I didn’t take any pictures but I owned a camera, a Kodak Retinette in a nice leather case. . .”

Upon returning to Stockholm in 1962, Petersen became fascinated with photography after seeing a picture by Christer Strömholm: “That picture was special. Footsteps in the snow in a cemetery in Paris. One camera, one lens and he caught the taste of the invisible.”

Strömholm’s picture, while rooted in reality, seemed to suggest that the dead were visiting each other at night in the Père Lachaise cemetery. That “taste of the invisible” is what drew Petersen to join Strömholm’s school, Fotoskolan. Later on, he also discovered Dutch photographer Ed Van der Elsken’s “Love on the Left Bank” and Agneta Ekman’s “Tall Maja,” a book about a forest nymph.

He felt that he needed to be close to people, and that painting and writing were too solitary: “It’s all about meeting people, identifying with them, sharing, listening, being a part of them, being transparent and learning.”

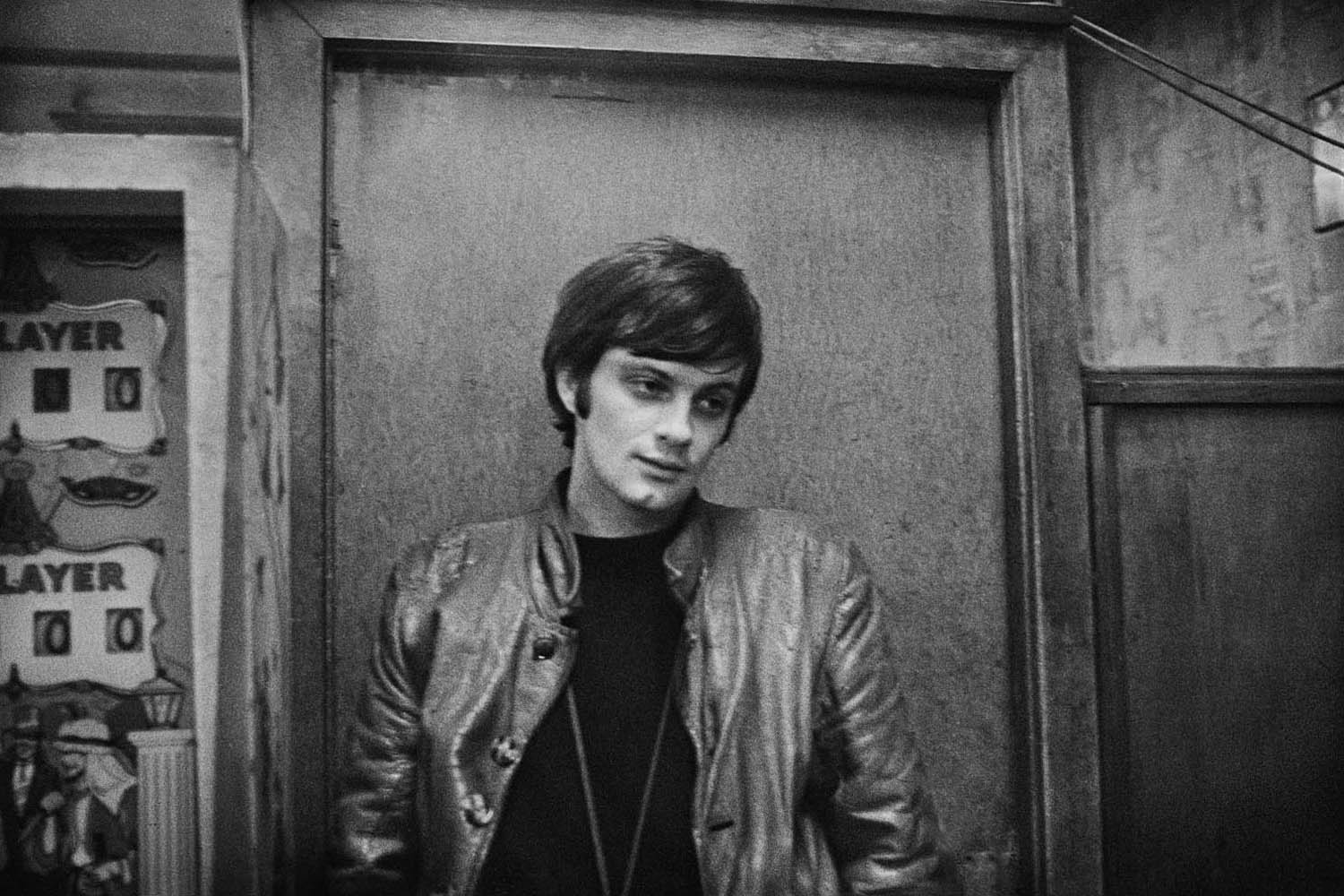

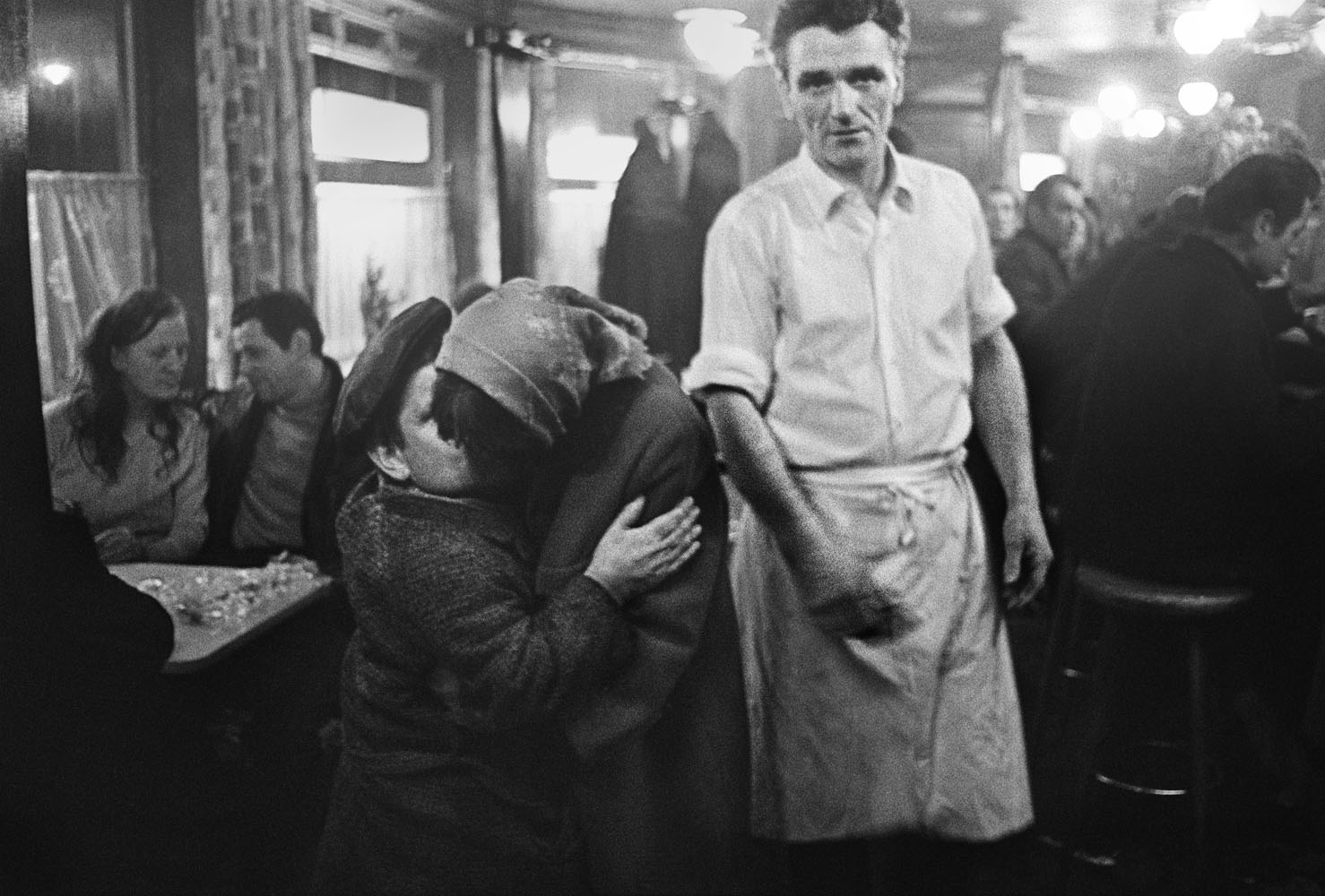

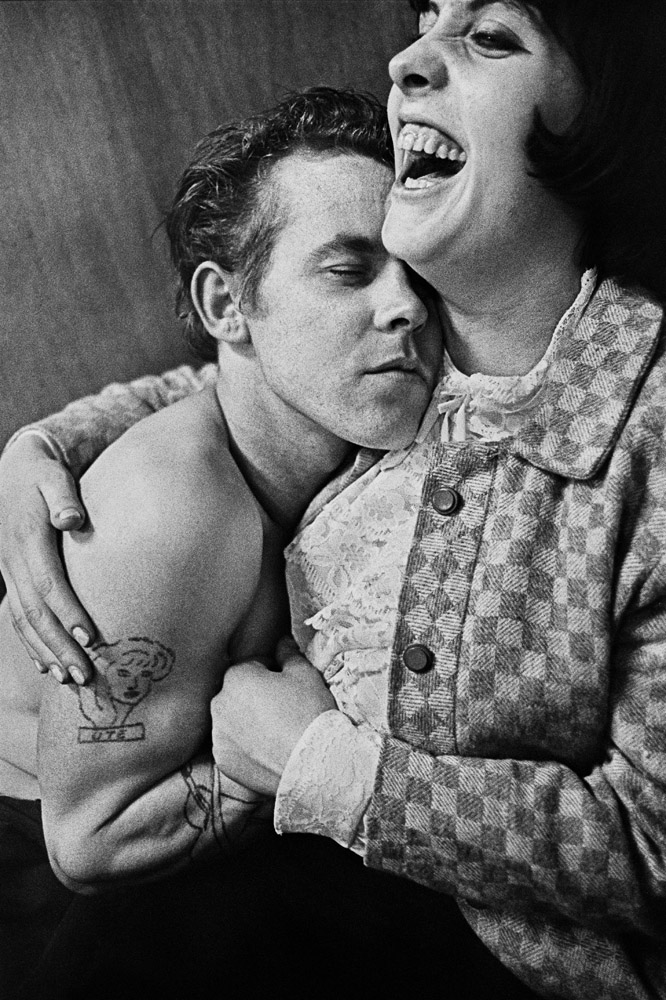

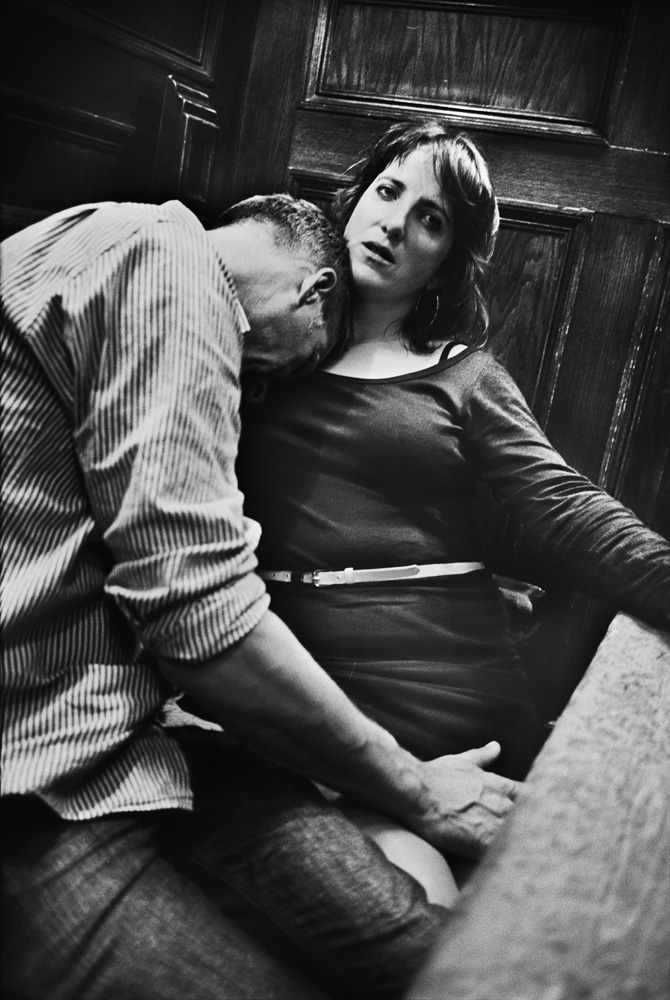

So in 1967, he started to photograph the late-night regulars (prostitutes, transvestites, drunks, lovers, drug addicts) in a bar in Hamburg, Café Lehmitz, and kept working there for three years. Even though the people there were destitute and often desperate, he found in them warmth, tolerance and sincerity. These qualities are reflected in his stark and tender portraits: Ninna wrapping herself in her fur coat with trembling hands, or Kleinchen clinging to her dancing partner.

Since then, Petersen has gone on to publish more than twenty books that feel like private diaries. Among his most striking photographs are those made in closed spaces: prisons, asylums, old age homes.

In the prison where he worked in 1984, for instance, he portrayed a man in his bathtub, his white body awkward and folded, too big for the space, like a metaphor of his situation; in his series on a mental hospital (1995), a patient is lying in a field of flowers, finding peace in nature, while others stare with vacant eyes, poignant images of loneliness. His explorations at the margins of society became empathetic, emotional portraits of those we would prefer to forget. “The surface is overestimated,” he says. “I am interested in what is behind, and if you are a curious type having a camera is a privilege. . . I could never spend time in a prison or a mental hospital if I didn’t have this working tool. I was interested in the idea of locked time and the concept of freedom, so I learned many things.”

Lately, Anders’ style has become looser, more open; his interest in composition has waned: “[Form] was more important for me when I started in the sixties, but an obviously poor composition isn’t automatically a ‘bad picture.’ In fact it can bring the opposite result, defining new and surprising energy in the poorly composed picture.”

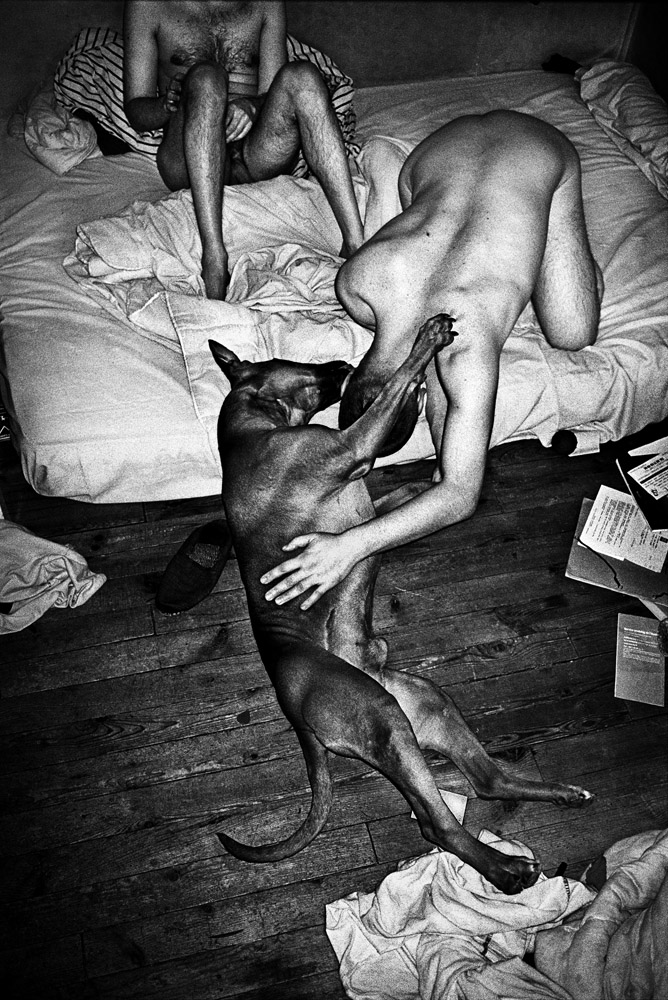

In From Back Home (2009), my favorite picture is probably a portrait of his mother in proud profile, making me think of Curtis’s portraits of American Indians. In his City Diary (2012) he photographs lovers with their bodies entwined, the soft touch of a mother’s hand brushing her small daughter’s cheek and his own battered face after a street fight. His tome on Rome (2012) has very romantic images, such as a woman’s hatted and veiled face or an old merry-go-round painted horse, but also surreal ones such as that of a fishmonger’s stall with the pulpy, glistening, translucent body of an octopus. The juxtaposition of images of animals with those of human bodies suggests some mysterious, unexplored bond that links the species. His book Soho mostly goes back to the world of the street with some night pictures in stark black and white that sometimes evoke the spirit of Brassai.

For his project To Belong, Anders has visited an Italian town, Reggio Emilia, in the aftermath of an earthquake. He extends his art to the landscape with lyrical and sensual views of vineyards suffused in fog in the early morning or trees decapitated by the quake, rows of cylinders of hay, wrapped in white, or a gigantic pile of branches slowly burning like a funereal pyre.

As these recent pictures demonstrate, after fifty years in photography Petersen’s approach is still fresh.

“The relationship to people is the same, I’m still naïve. Still looking for the identifying process. I have never been looking for what is separating us, but for what brings us together. I don’t want to just steal the situation and disappear,” Petersen adds. “I also want to bring it back, in one way or another, at least as a memory.”

Anders Petersen’s black and white contain all the colors of life, the pangs of longing, the shapes of shared memories. As he says, “I do not photograph what I see; I photograph what I feel.”

Anders Petersen is a Swedish photographer living in Stockholm. His work is on view from November 13, 2013 – February 2, 2014 at the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris.

Carole Naggar is a photo historian and poet. She recently wrote for LightBox on Bruce Davidson’s photographs of Los Angeles.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- TIME’s Top 10 Photos of 2024

- Why Gen Z Is Drinking Less

- The Best Movies About Cooking

- Why Is Anxiety Worse at Night?

- A Head-to-Toe Guide to Treating Dry Skin

- Why Street Cats Are Taking Over Urban Neighborhoods

- Column: Jimmy Carter’s Global Legacy Was Moral Clarity

Contact us at letters@time.com