When I first went to Europe in 2007, my conventionally religious father suggested that I cut my beard because of the situation after 9/11. I didn’t listen, and as a result, for the first time, my beard became a security issue. I was stopped by security at every possible immigration checkpoint, and even at museums. People looked at me strangely in the Paris Metro. I remember cautious voices asking me: “Is that your bag?”

From that moment, I was forced to start thinking about the relation of my appearance to my identity and religion. I decided to interrogate and to challenge Islam, and religion, and how it is represented through the medium I knew best: photography.

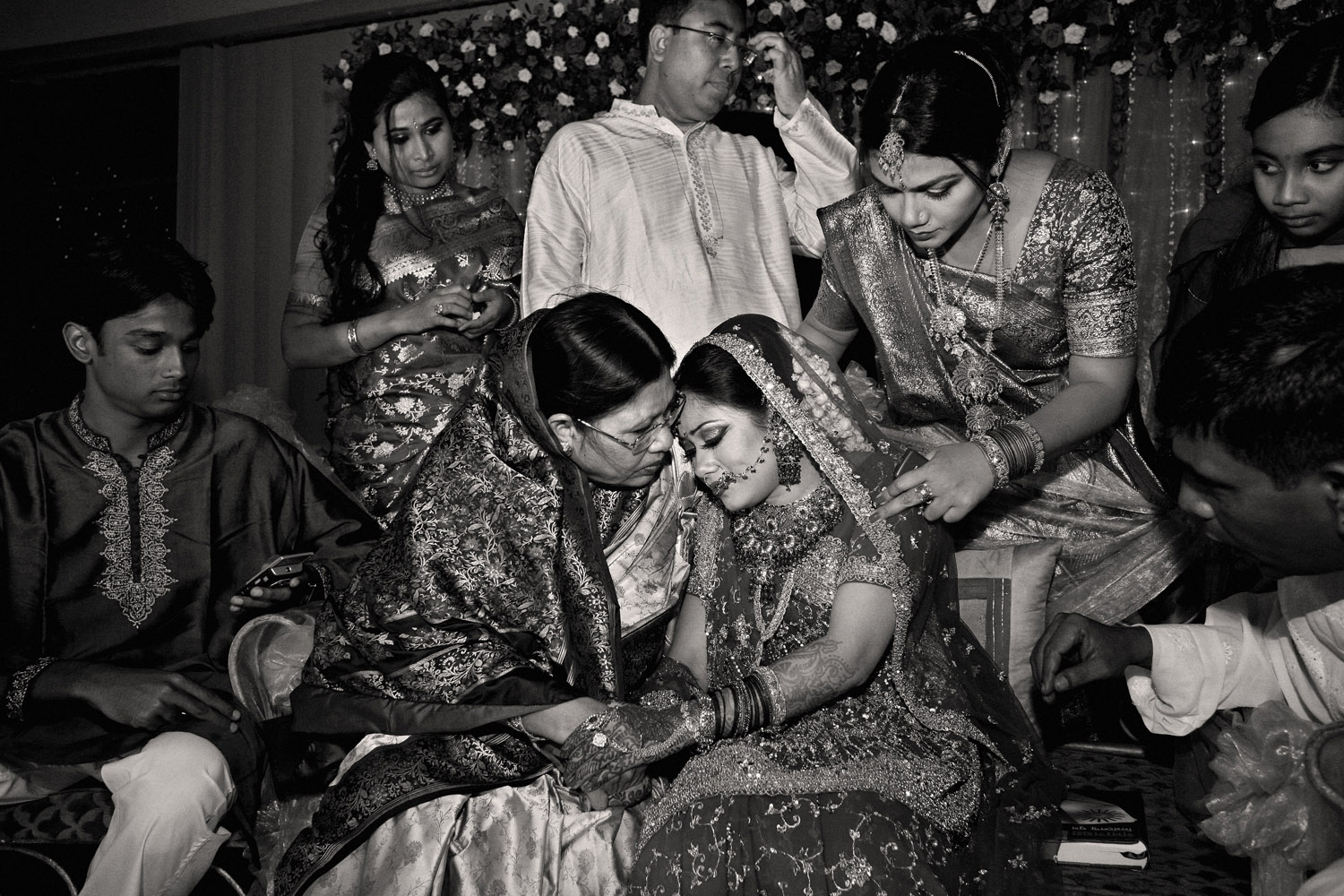

But there was another twist: upon returning from the Hajj (the pilgrimage to Mecca), my sister Munmun began wearing a hejab. Her decision was difficult for me to accept. During our childhood, religion was never an issue. Later, I realized that her hejab was an affirmation of her belief, rather than a sign of oppression. I realized that even in my family, and within my ever-changing self, Islam has many different interpretations.

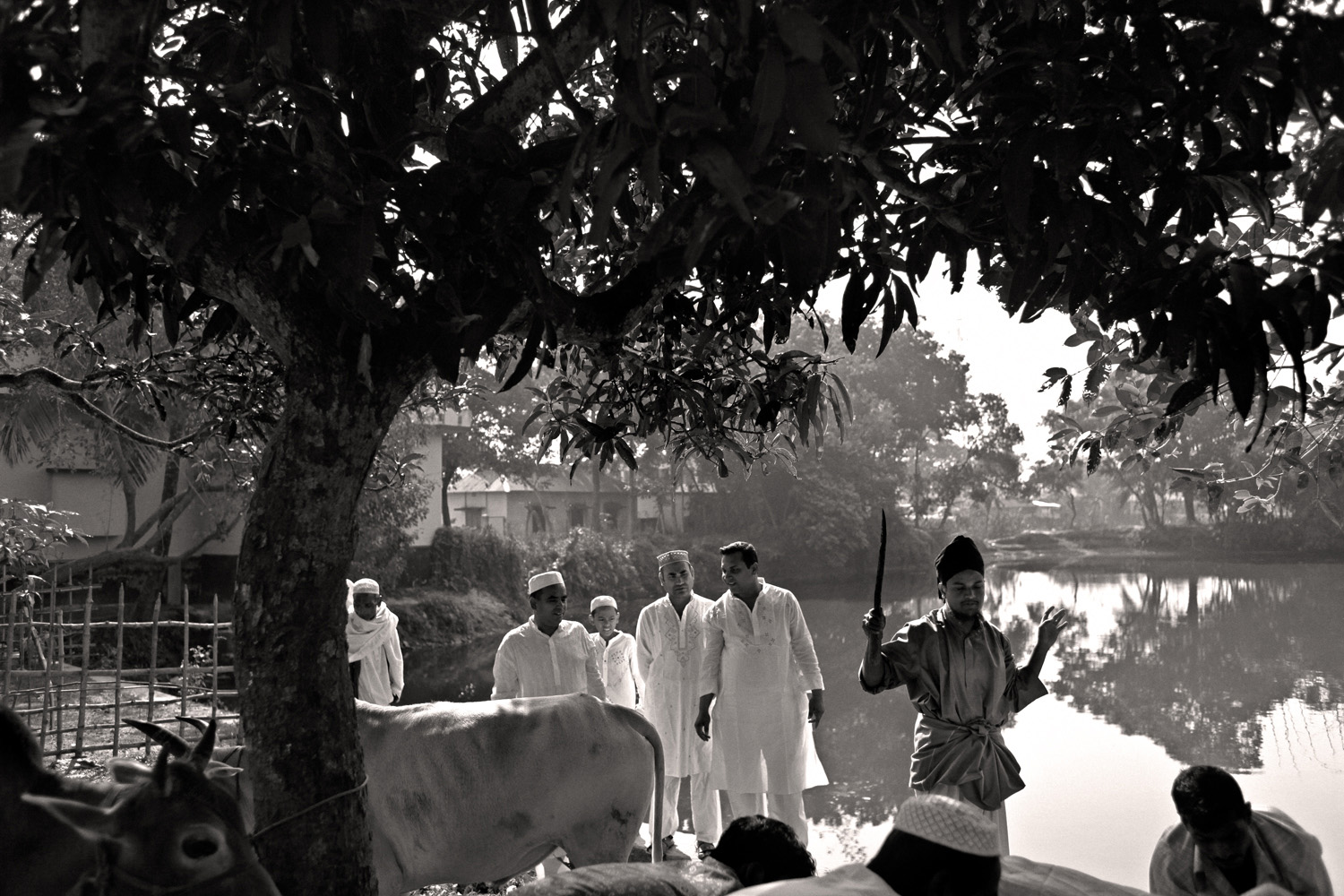

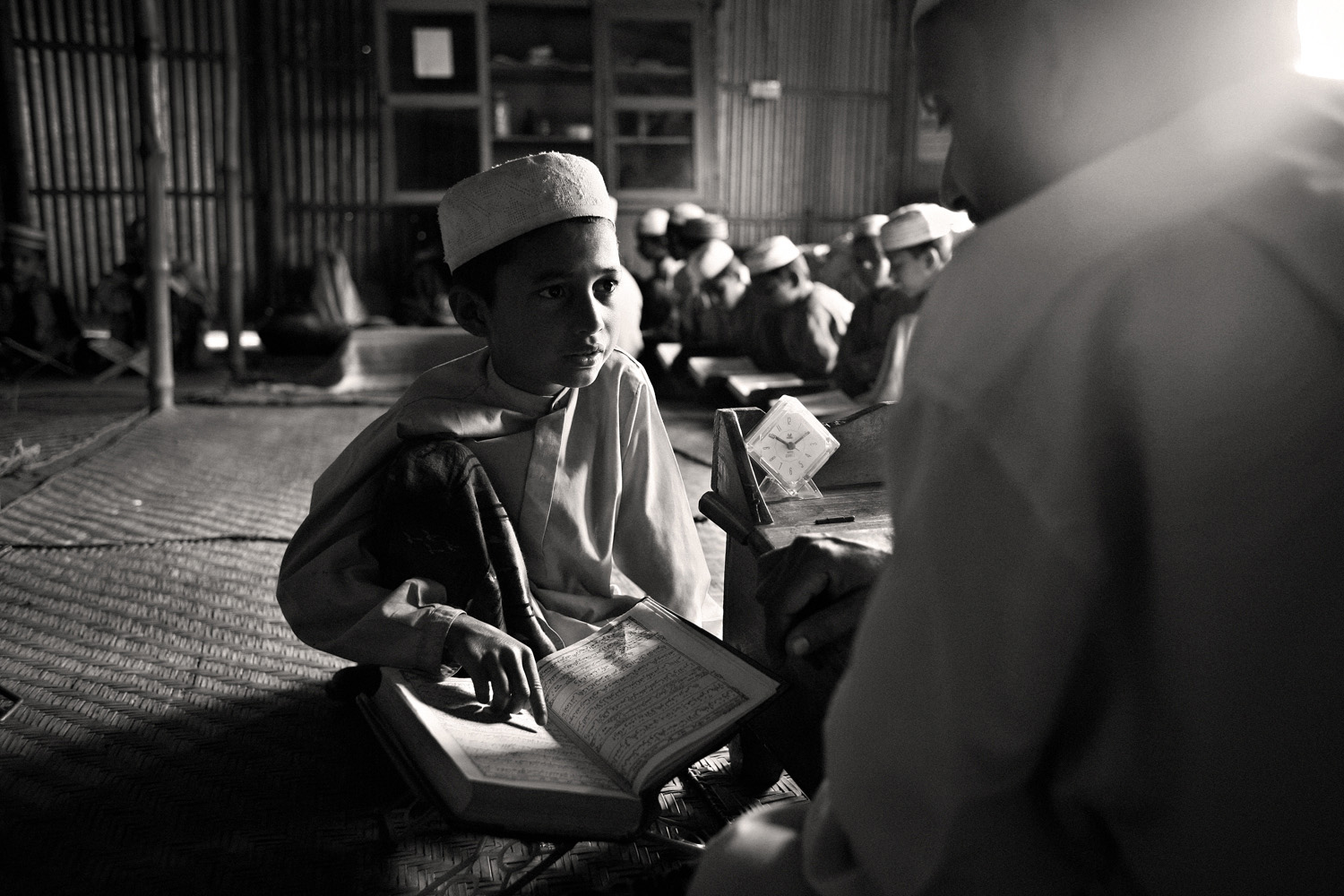

Terrorism, fundamentalism, veil, bomb, Taliban, Jihadi, militant, fanatic — these are words tied to Islam by the mainstream media. But the reality of the Islam I grew up with is far more complex than these simple words. Islam in Bangladesh is like the multiple colors of a mirror under the sun: veil and lipsticks, verses and azans (call to prayer), jeans and beard, all together. This is a story about little fragments that don’t make it to the front pages of newspapers. This is a story about how we see Islam.

As a nation, we are proud of our cultural heritage as well as our religious one. On one hand, we have traditional ulemmas (scholars) who help run the mosque and teach us religious beliefs; on the other hand, we have all-night folk song festivals, with spiritual devotees challenging us to consider the traditional values of life and other philosophical questions. We celebrate Bangla New Year by singing Tagore songs. We light candles at our weddings, as well as at our protests. Hinduism, Buddhism and Islam were practiced in this land for thousands of years. Thus a complex Bengali culture has developed, interweaving different rites and practices from the religions. This is Islam in Bangladesh.

Munem Wasif is a Bangladeshi photographer represented by Agence VU. His new book, Belonging, was recently published by Clémentine de la Féronnière. In God We Trust was supported in part by Fabrica, Benetton’s research communication center.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com