In 1968, I was a suburban teenager who occasionally hopped a bus from Northland, the nation’s first suburban shopping mall, to the downtown marble palaces of Detroit’s library and art museum. Enrico Natali might have captured me then, a 14-year-old girl, trying to move past the residue of anger and fear left by the 1967 riots, to explore the city’s cultural riches on my own.

This was not just any year in the life or Detroit or America, but a moment when hope and despair mixed like chemicals in a test tube. To Natali, Detroit must have seemed the perfect middle-of-America spot to witness the nation’s combustible spirit: arriving in 1967, he would stay three years. The images were displayed at the Art Institute of Chicago in 1969 as a broad sweep of “New American Life,” one not specific to Detroit.

In reality and in retrospect, however, the photos are specific.

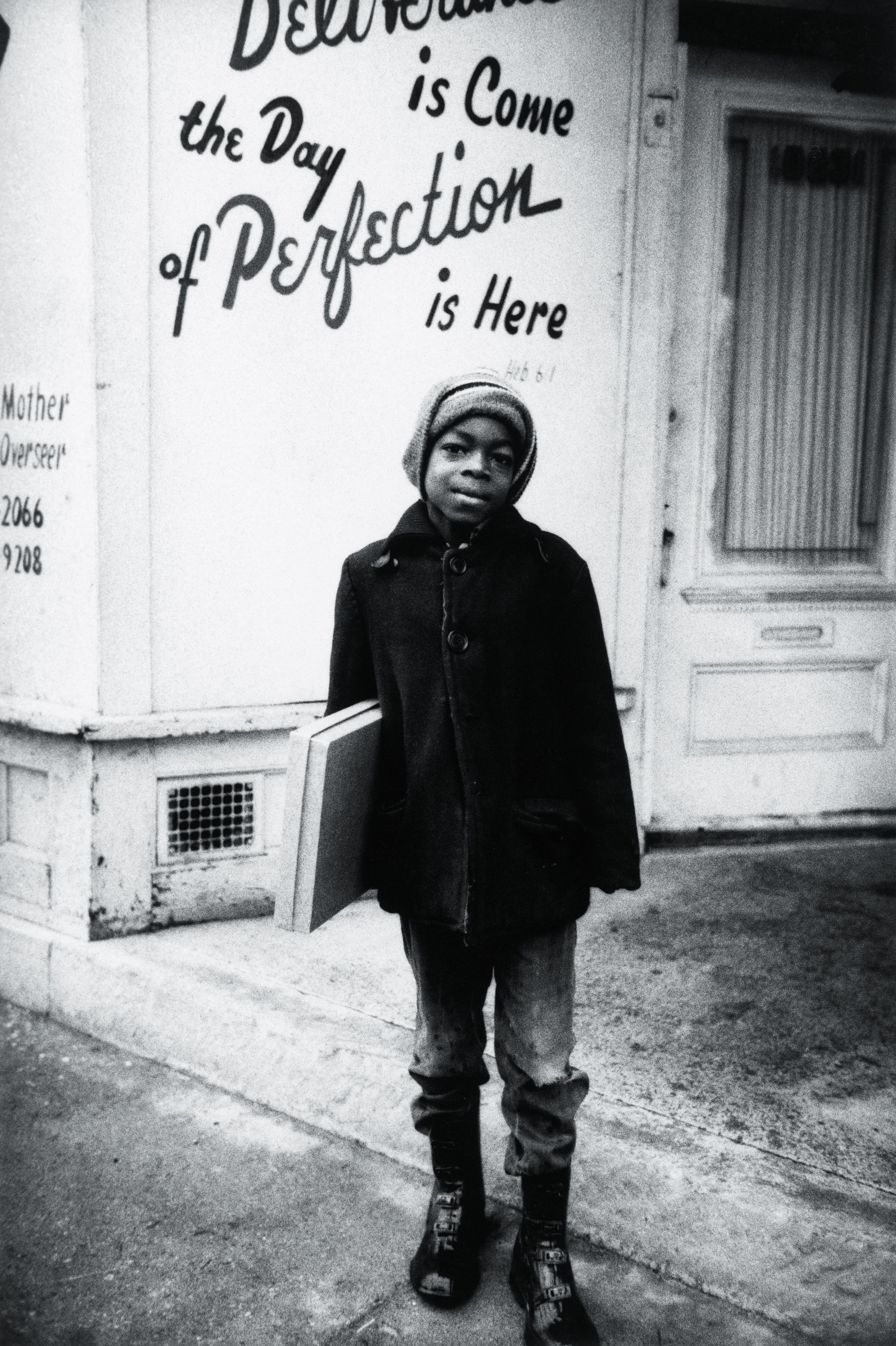

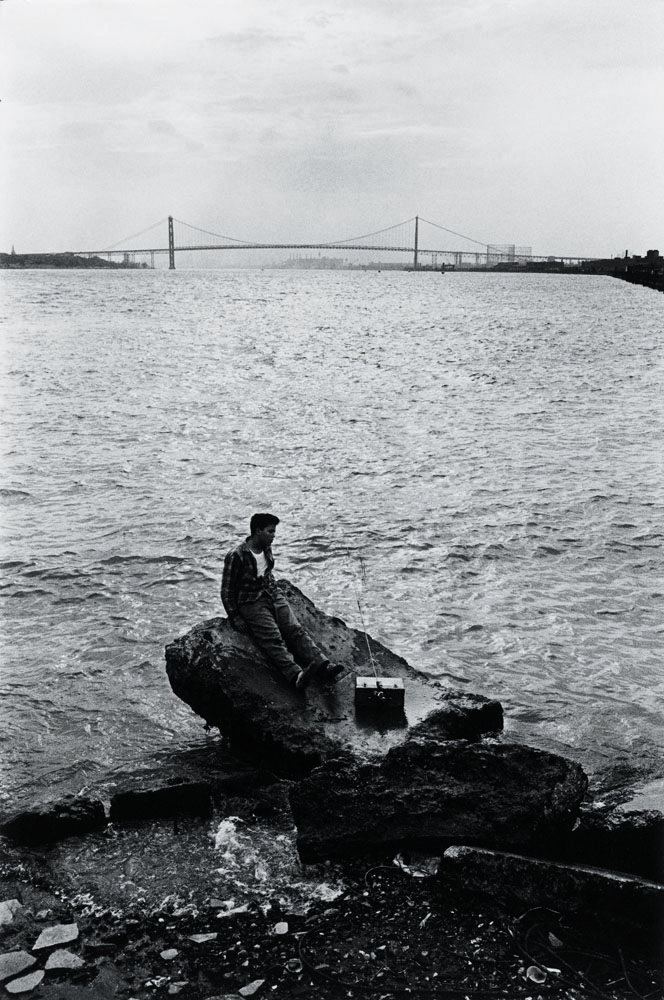

Today, Detroit is an exotic and extreme place whose grassy fields and acres upon acres of concrete ruins evoke horror and shame even from those who live here. On the surface, what Natali caught in these photographs is normality, a Detroit that’s neither urban outlier nor crucible of failure. If, when viewing his pictures, one can forget the city’s fate, Natali captured a kind of generic — perhaps an idealized — urban America, a place where even in a year of assassinations, racial violence and an Apollo launch, more than a million people lived, died, toiled, loved, fought and, individually and collectively, caught their breath.

Looking at the photographs in 2013, it’s impossible not to see a city clearly on the cusp. The faces are optimistic – and just a little bit wary. The people of Natali’s Detroit are young, mostly white, and – in those pre-high fructose syrup days — noticeably thinner than their modern counterparts. From the ossified society matrons in their ball gowns, to the young career women in their bouffant hairdos and nylon stockings, there’s a sense of unease in each frame, a feeling you can’t quite name.

In the words of a Buffalo Springfield song, “For What It’s Worth,” that was a hit at the time: There’s something happening here.

All photographs stop time, but Natali’s do so with uncanny precision. Even as Detroit’s downtown office buildings are now refilling with new faces – young, ethnically diverse, college educated – it’s difficult to remember when the city was fully alive and inhabited. It was still a majority white city then, and Natali portrays the divide without politicizing it: An all-white high school basketball team, a young man in a Black Panther beret. On the wall behind a young woman, primly dressed and coiffed, there’s a striking portrait of a man with an Afro.

Maybe because work, labor, has in large part defined Detroit for so long, I especially enjoy the photographs of people at their jobs. Men in white shirts and ties, overseeing a room full of the era’s massive computers. Or the image of a confident Henry Ford II, the brand’s famous oval logo in the background. Ford (the man) reigned then, untroubled, over a manufacturing empire, knowing his grandfather had effectively created the city’s then-huge middle class.

American prosperity touched everyone back then, in one way or another. Natali shows black and white families, in separate frames, in living rooms that mirror each other, down to the nearly identical floor lamps. Storefronts are occupied. A shoemaker plies his trade. These are people buoyed by the city’s manufacturing prowess, riding a long and prosperous wave. This was what the city looked like when men (and some women) filled the city’s office skyscrapers and factories.

Nothing in these pictures accurately foretells what’s to come. These are people looking forward, sometimes watchful or anxious, but never despairing. Natali catches the hauteur of the upper classes, the nagging (but far-from-paralyzing) anxiety of the middle, the emergence of a counter-culture — but he never lingers too long. In this Detroit of his, one can imagine that anything might happen — anything but that, 45 years hence, this great city might be gasping for air.

Enrico Natali is an American photographer living in California. A new edition of Natali’s Detroit 1968, with an introduction by Mark Binelli, is available from Foggy Notion Books.

Laura Berman is the Detroit News metro columnist and a longtime chronicler of the city’s characters, crises, and multiple attempts at urban renaissance. The winner of a National Headliner Award for column-writing and contributor to national magazines, she writes twice-weekly about her crumbling, astonishing home town. Follow her on Twitter @LauraBerman.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com