“I enjoy taking part in life,” says Magnum photographer Jacob Aue Sobol. “When I photograph someone, it’s all about the exchange with that other person and what happens there. It’s as much about myself and what grows from this encounter as it is about the subject.”

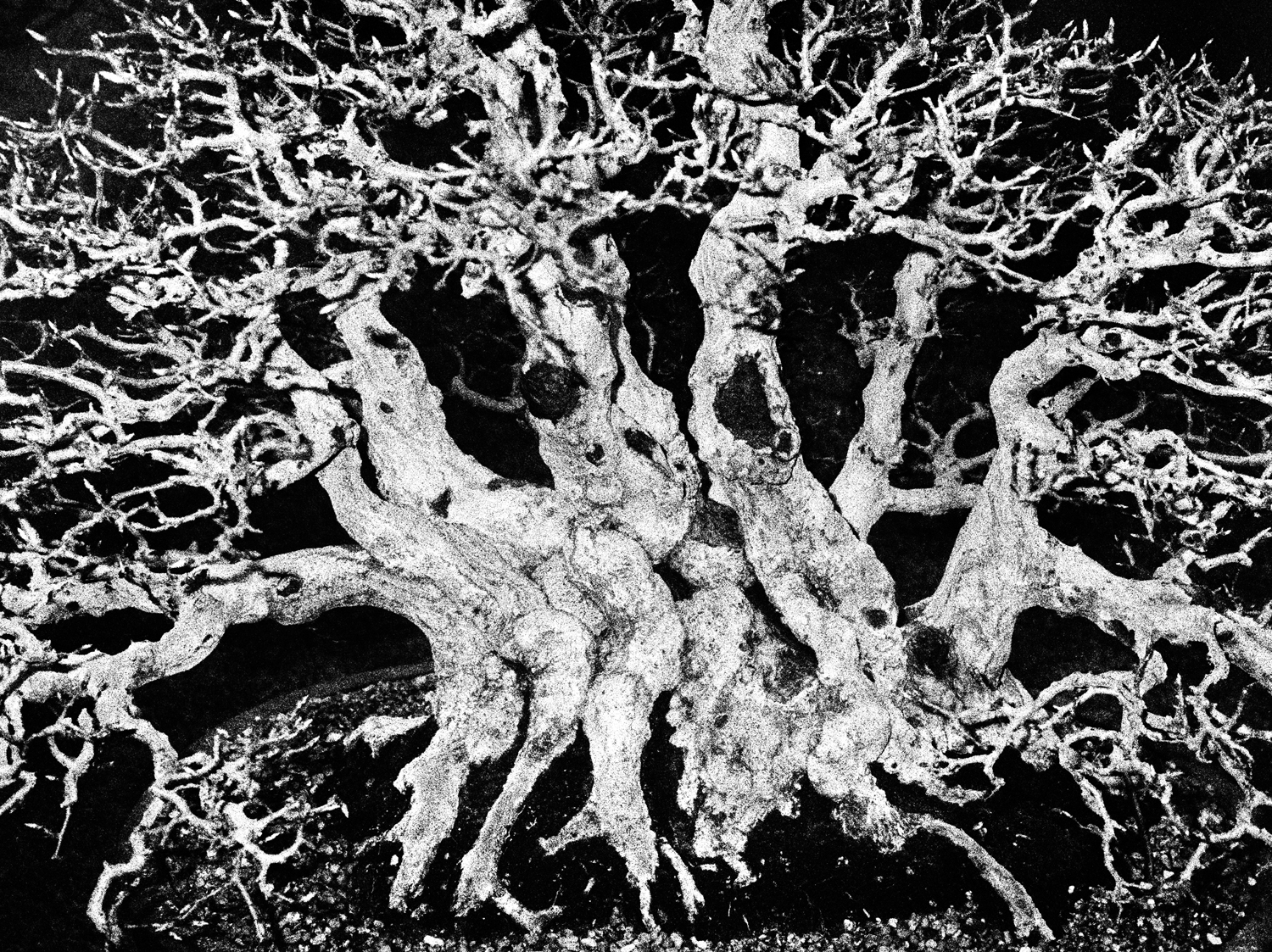

Roughly 13 years of Sobol’s raw, grainy, intimate stream-of-consciousness-style photographs are featured in a new book this month from Dewi Lewis Publishing called Veins. The book is split down the middle, Sobol sharing the volume with renowned Swedish photographer Anders Petersen, whose work has a deep aesthetic and methodic connection.

“The way we approach photography, it all comes from the same family tree,” Sobol says. Petersen taught him very briefly years ago at a school promoting the long tradition and increasingly popular mode of diaristic photography. “From the beginning, you are encouraged to develop this connection between your own inner life and the images you create.”

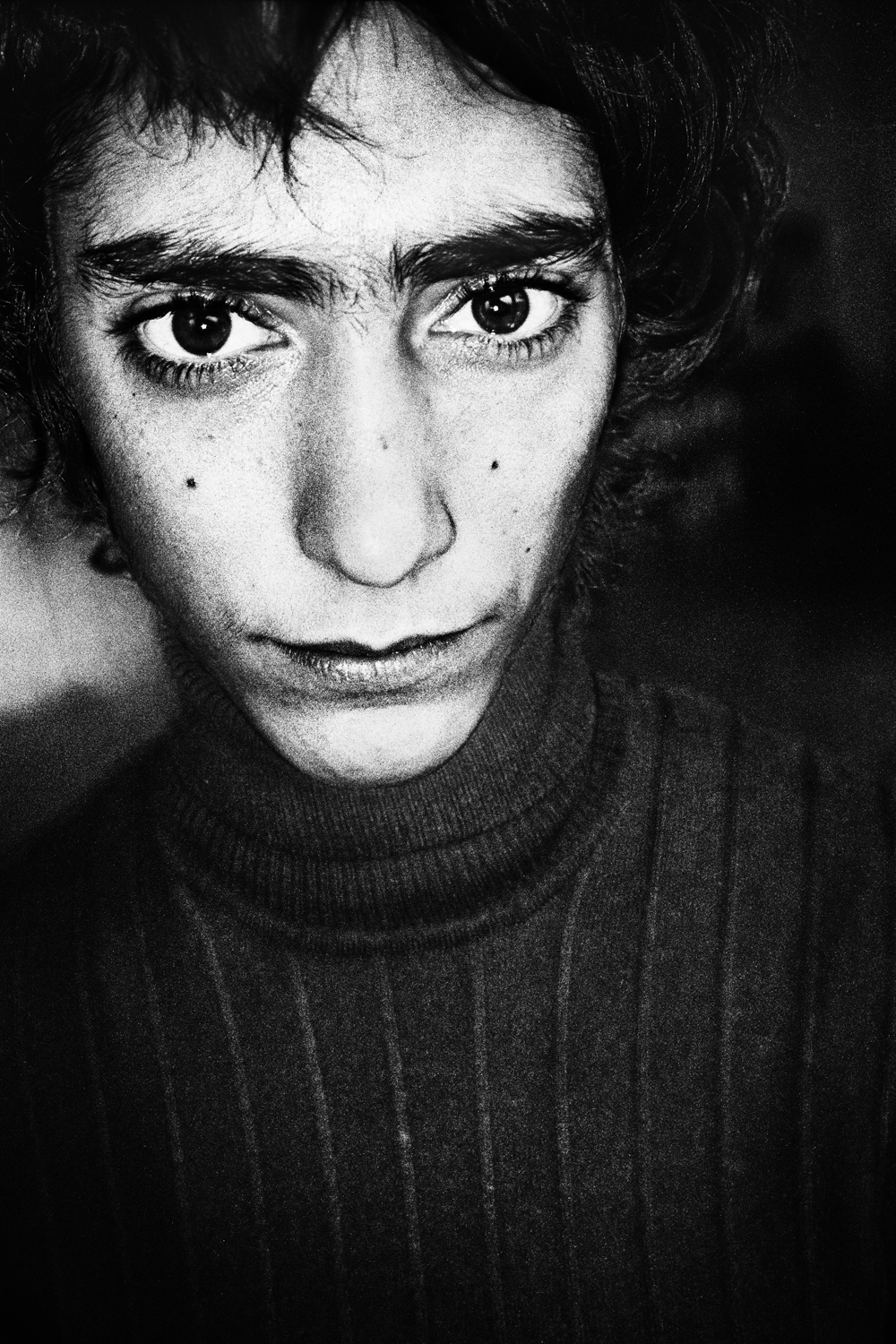

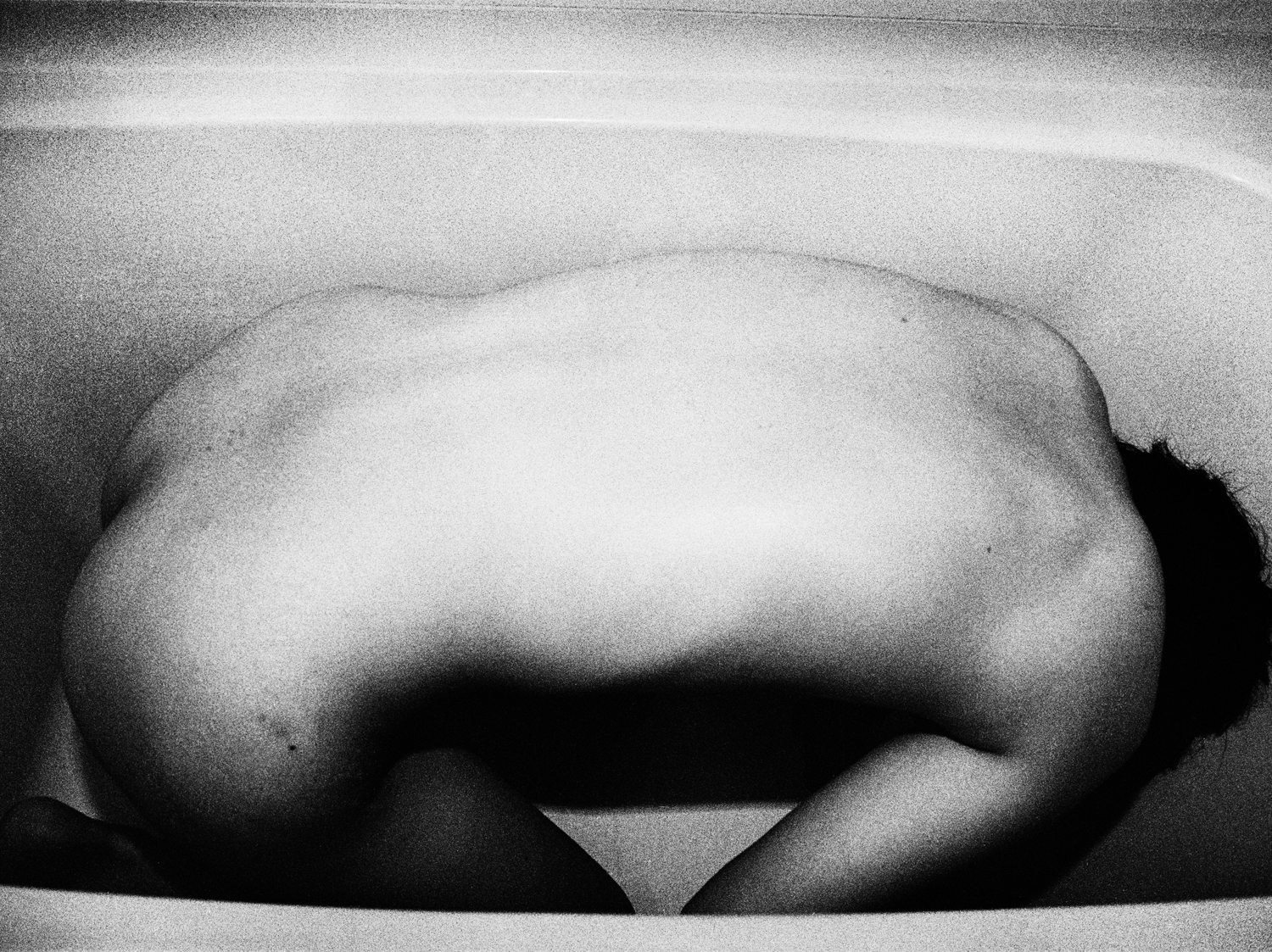

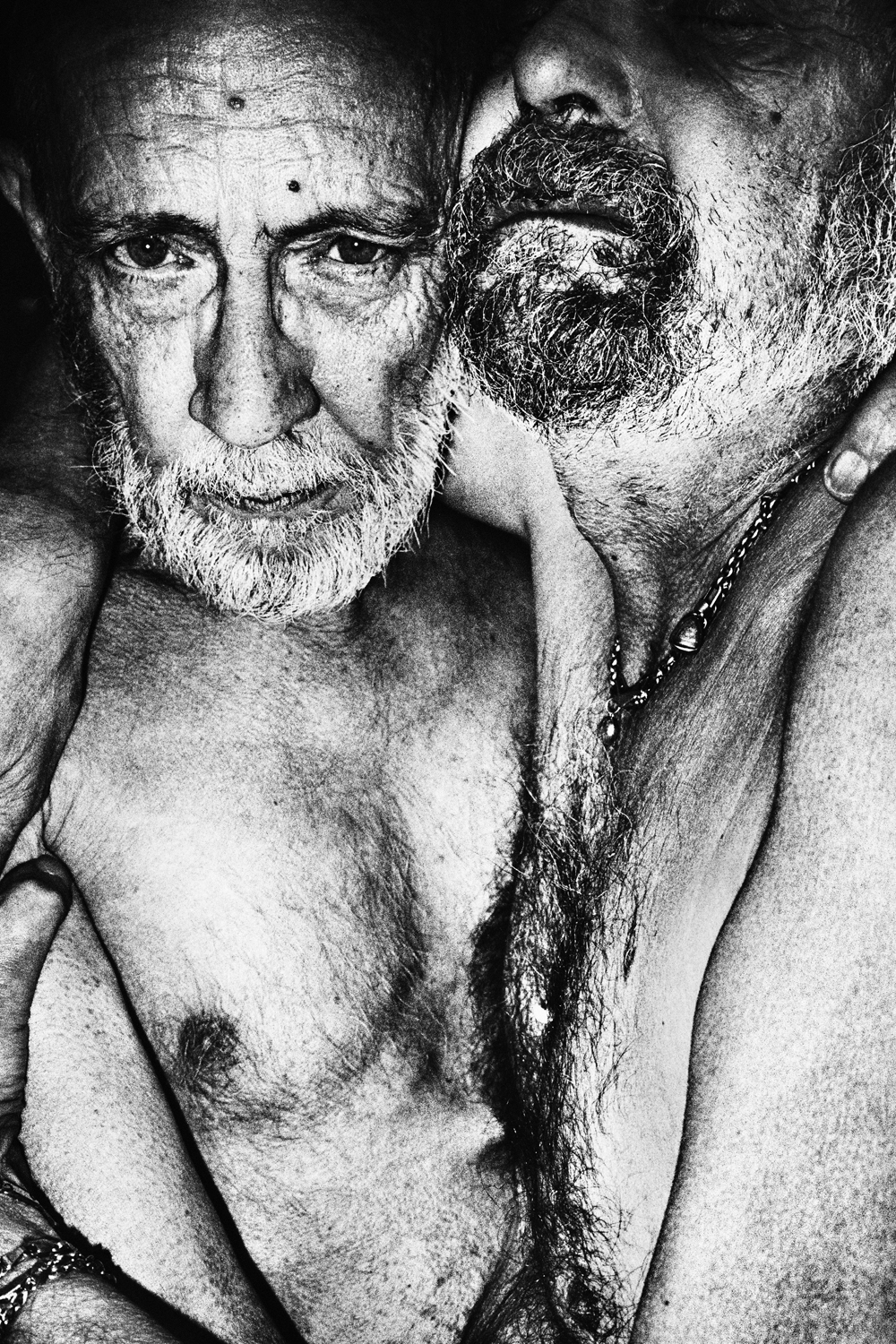

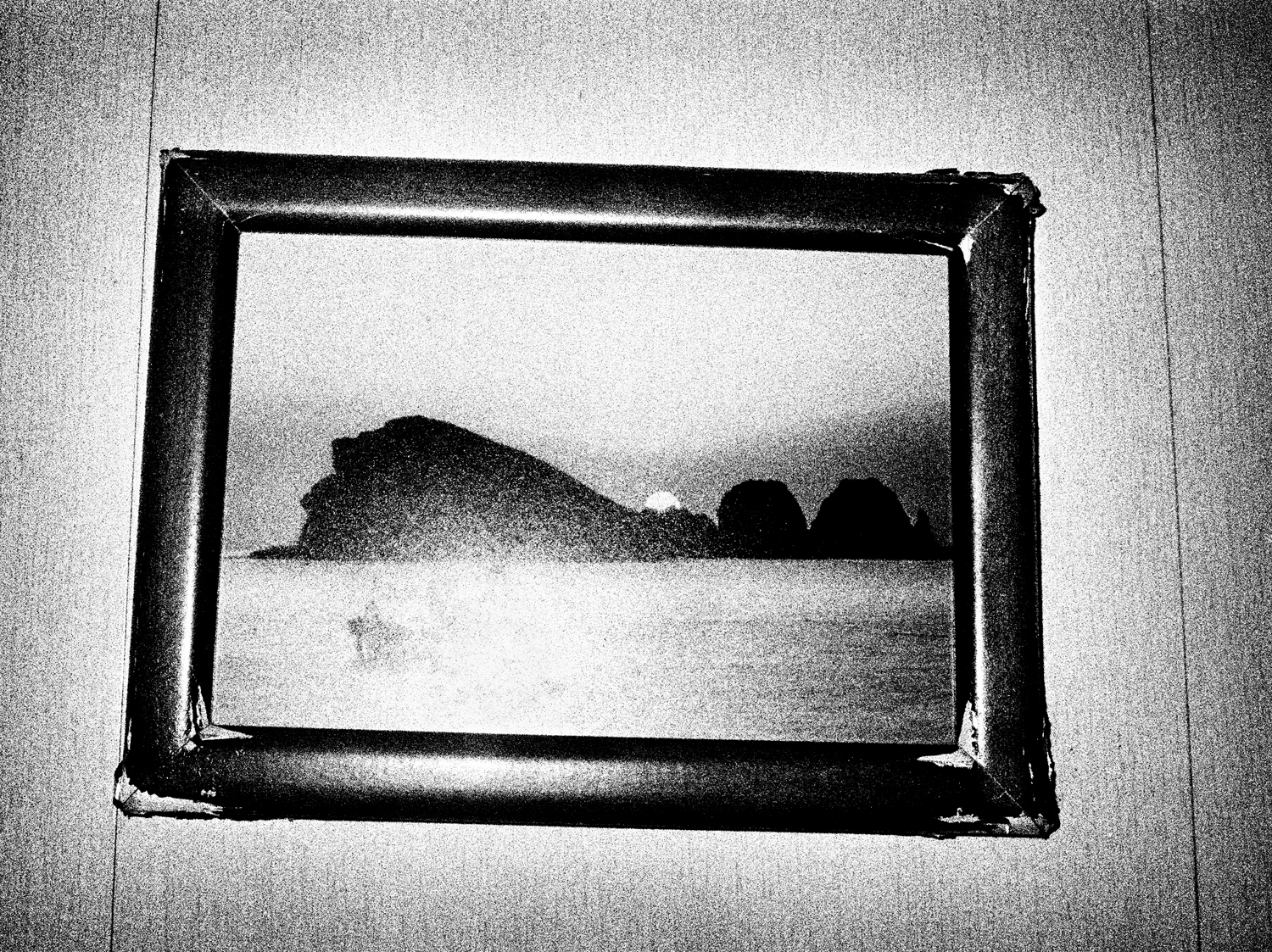

Eschewing the straight documentary approach of many Magnum photographers, the task of using the camera to make “objective, dispassionate records of the world,” as photo critic Gerry Badger terms in his introduction to the book, Sobol instead adopts a highly subjective, participatory method, capturing the energy, passion and ambiguity of life as it is experienced, and visualized, by a photographer. His physical presence in each picture is as apparent as his aesthetic and technical brush stroke.

This new book is the first time he made a single sequence cutting up and re-editing together his numerous projects over the years, going back to his first major body of work, Sabine, which had launched his aesthetic direction and changed his reason for making pictures. He was 23 then and moved to Greenland as a documentary photographer — somewhat of a difficult, tense situation for the native of Denmark moving to a former Danish colony. There, he fell in love with an Inuit woman, which was considered taboo, and for a while stopped taking pictures. “I was living with her family and it was more important at the time to become a skilled fisherman, a hunter,” he said.

One day, he found Sabine “in an extremely good mood, dancing around the house. I was in love with her and I wanted to remember and keep this feeling, this moment.” He had a pocket-sized point-and-shoot analog camera on him, and for the first time in many months, he quickly made an exposure.

“Instead of doing a documentary about the clash between the cultures, which is the obvious thing, I chose to tell a love story, a story about myself falling in love with Sabine — which can be a statement in itself,” he says. “I realized this was a good way for me to work. I didn’t need that identity as a photographer, I didn’t need all the equipment, I just needed to be Sabine’s boyfriend and take part in life and I could take pictures with this small pocket camera when I felt the need for it.”

This process of pairing down technologically and re-focusing his approach led to the unmistakably consistent look of his pictures — the bold contrast, the intense grain, the high-energy motion blur. Despite, or perhaps because of the limits imposed by the point-and-shoot camera and it’s single normal lens, he exerts tremendous control over his stylized vision of the world. Formally, he pushes the limits of the medium, using high-speed film and a fill flash, a rather unusual approach that gives skin and hair an almost porcelain quality.

The distinctive grit of his imagery exists on the level of content, as well, as he seeks through his wanderings intimate, fragile encounters with certain other types of limits.

“There is a compulsion to photograph people at the edge, on the edge of sanity, at the edges of society, down the wrong end of the Reeperbahn in Hamburg, or in an Inuit settlement in Greenland,” Badger writes. “Their concern is with the often terrible, compulsive, largely uncontrollable, and self-destructive urges lurking within us all.”

The result at times can come across a little unnerving, voyeuristic or too close for comfort for some viewers — which need not be a bad thing. Sobol draws “subjects into a kind of confession that seems rather more than exhibitionism or a desperate craving for attention, and might actually be good for the soul,” Badger writes, “…that is to say, the collective soul of subject, photographer, and audience.”

Jacob Aue Sobol is a member of Magnum Photos and a recipient of the World Press Photo 1st prize, Daily Life stories. His work is on view at Leica Gallery, Warsaw through Nov. 17, 2013; at Athens Fotofestival, Greece from Nov. 1, 2013 – Nov. 20, 2013; and at Maison du Danemark, Paris Photo from Nov. 15, 2013 – Dec. 15, 2013. Follow him on Facebook.

Veins: Anders Petersen & Jacob Aue Sobol is available through Dewi Lewis Publishing from October 2013.

Eugene Reznik is a Brooklyn-based photographer and writer. Follow him on Twitter @eugene_reznik.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com