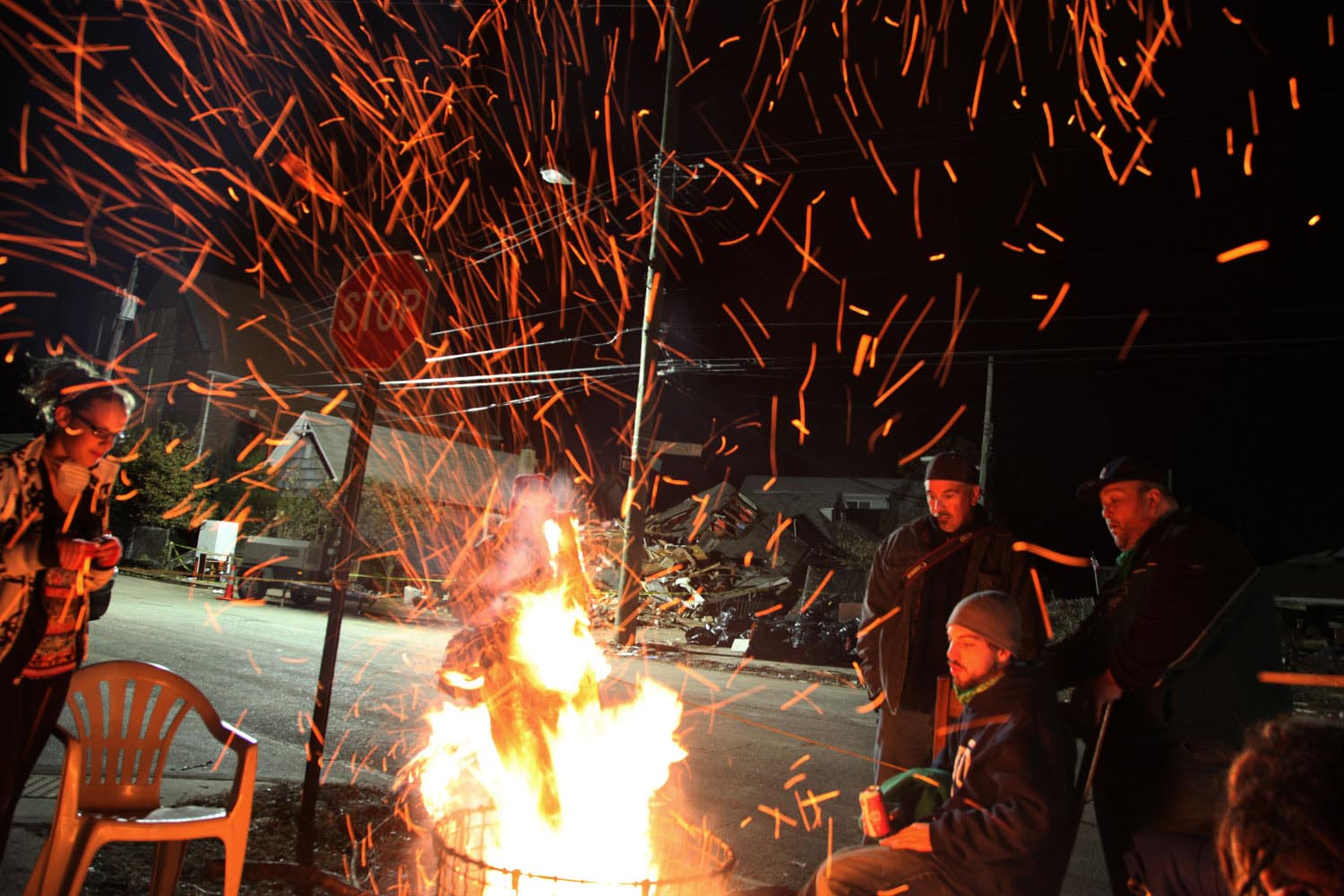

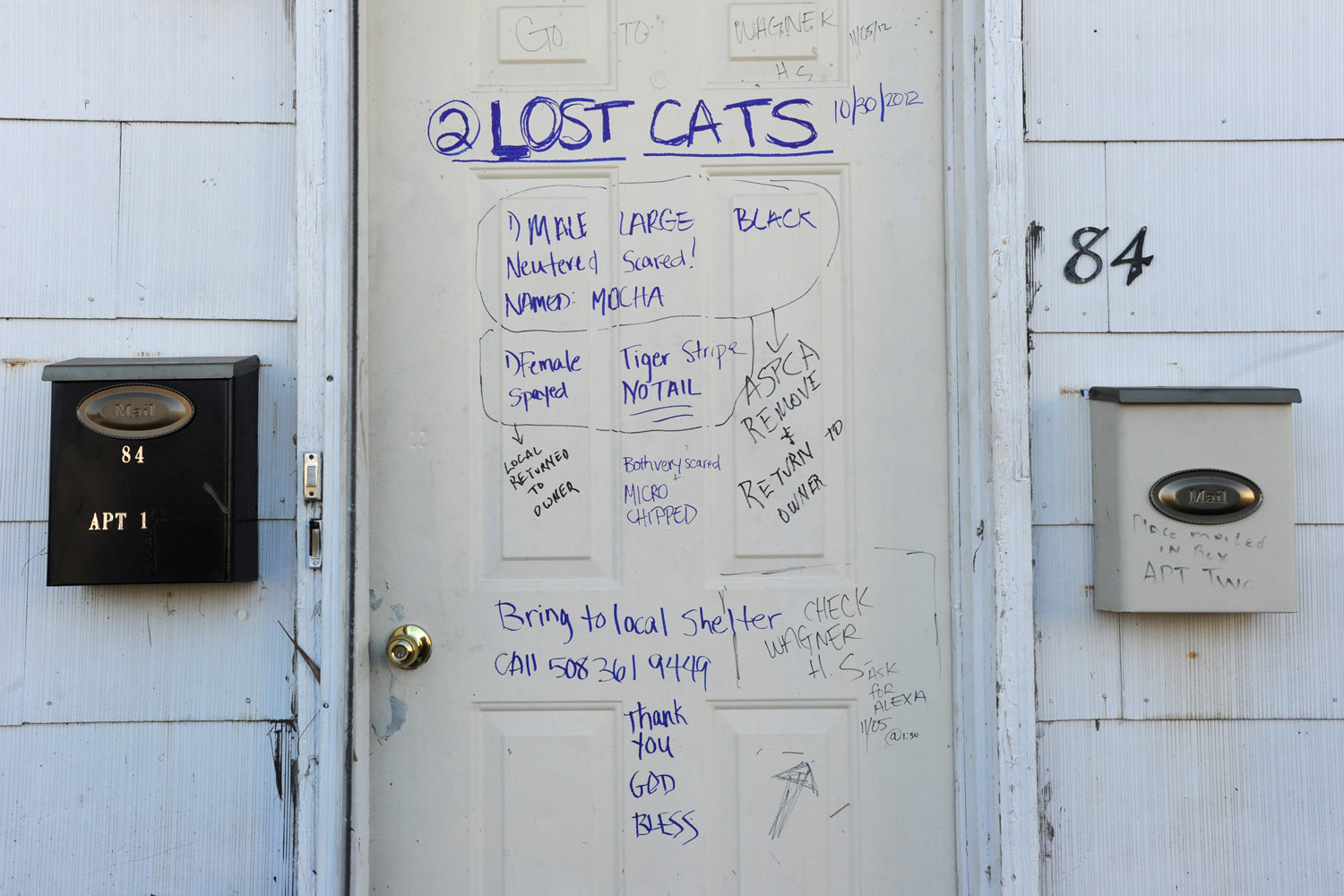

Now that so many millions of people have cellphones with cameras and new photographic technologies are emerging that will allow individuals to constantly record their lives, there is a growing potential for communities to portray themselves, including during periods of disaster. Instagram, for example, allows professionals and amateurs alike to immediately upload images; during Hurricane Sandy last year, ten photos tagged to the storm were uploaded every second; 800,000 pictures were uploaded in all. In contrast, the monumental, multi-year Farm Security Administration program created during the New Deal that focused on American rural poverty with photographers such as Walker Evans, Dorothea Lange, Russell Lee, Gordon Parks, Arthur Rothstein and Ben Shahn, produced roughly 250,000 images total.

Whereas cellphone photography by citizens first became a mainstay of news reporting during the bombing of the London Underground in 2005, Instagram emerged as a prominent real-time platform of visual information during last year’s superstorm; Time, for example, had five professional photographers on assignment using their iPhones, and Ben Lowy’s Instagram image made the magazine’s cover. Unlike previous large-scale documentations, Instagram images can be produced and seen in real time, allowing viewers far from the scene to watch as the calamity unfolds. Streams of images from individual photographers and organizations are provided to masses of “followers,” while also allowing interested viewers to skim through groups of photographs according to particular themes.

Other major publications also published cellphone pictures by the public (this is now the norm), and one year later a book of Instagram photos, #SANDY: Seen Through The iPhones of Acclaimed Photographers, is being planned to raise money for charities, while exhibits such as Rising Waters: Photographs of Sandy (recently on view at New York’s Governors Island) and at the Museum of the City of New York are showing photographs from a variety of sources. This mix of work by professionals and amateurs was previously used, with great success, in Here is New York: A Democracy of Photographs, the exhibition that opened immediately after the September 11 attacks in a vacant storefront; inkjet prints were hung on clotheslines, and only after making a $25 charitable contribution for one would the identity of its author—fireman, neighbor, student, professional—be revealed.

Besides providing channels to bypass conventional media outlets, Instagram also allows photographers to easily and instantly transform the look of their imagery with a choice of numerous digital filters, many of which reference earlier photographic processes. In seconds the photographer can crop his or her image into a square (required for Instagram), dramatically change the color balance, add a frame, or leave the image as it was. As Instagram’s co-founders put it on their site, “Snap a photo with your mobile phone, then choose a filter to transform the image into a memory to keep around forever.” But memory is not the only goal: “Mobile photos always come out looking mediocre. Our awesome looking filters transform your photos into professional-looking snapshots.”

An advantage of Instagram is that it forces the photographer to be close to the action; at this point, there are no powerful zoom lenses available. And even with the considerable filtering, there seems to be less of the targeted retouching and compositing that’s possible with more elaborate software such as Photoshop. There also can be something personal and diaristic about the small, snapshot-like Instagram image, lacking the visual sophistication of larger photographic formats. And as each Instagram image arrives individually on viewers’ mobile phones, it provides a respite, of sorts, from the visual chaos of the Web.

(Although the individual nature of the images does not allow comparisons between photos. One of the most interesting would have been to compare the now-famous New York magazine cover image from the sky by Iwan Baan, showing the city’s downtown in darkness because of the electrical outage, with another photographer’s image from a different perspective that shows a Goldman Sachs building still illuminated in the financial district’s obscurity by its own generator. These two would have created an interesting tandem commenting on community and preparedness, or the lack of each.)

There are many critics, some of them quite vocal, who detest the nostalgic look of much of the imagery on Instagram, arguing that the service’s filters render it so stylized that the content is obscured. Certainly the ability of an Instagram image to evoke an undeserved nostalgia can be off-putting, especially when dealing with painful contemporary events. Rendering the present as the distant or semi-distant past via an imitation of an old snapshot may diminish what the people in the pictures, and others like them, are at that moment feeling. Rather than evoking “instant” and “telegram” (the two words from which the name Instagram was synthesized), many filtered Instagram images can be reminiscent of a 1960s or ‘70s postcard meandering its way to a destination, a tryst with a fabricated past.

Instagram, bought last year by Facebook for one billion dollars, will soon face competition, including from Google Glass as well as other technologies that allow one to “lifelog,” making a nearly continuous record of everyday experiences. And the soon-to-be-released Narrative is a small, buttonless camera that can be attached to a shirt that will automatically take a photograph every thirty seconds, all day long, and group the vast number of images that are produced according to their metadata, while selecting what it considers the more significant ones. (Several photographic organizations, including the American Society of Media Photographers, are also currently campaigning against Instagram’s terms of use, arguing that they allow Instagram to use and license a photographer’s imagery in perpetuity, while holding the photographer responsible for attorney and other fees in case of any litigation concerning the image.)

But not all disasters are the same. Whereas Hurricane Sandy was a catastrophe that those in the Northeastern United States suffered through together, sharing each other’s vulnerability, other circumstances may be more problematic. What might have been the result if those trapped inside the World Trade Towers on September 11 had possessed cellphone cameras? Would it have been enlightening for others on the outside if they were able to distribute images of their terrible predicament, or would large amounts of such first-person imagery have provoked an ugly voyeurism amounting to re-victimization? Would these images have further increased the trauma for a horrified, largely powerless public to even more intolerable levels, and with it the calls for vengeance?

These questions can also be asked of the events now taking place in Syria, amply documented in videos and photographs, many by civilians. How does one look at such atrocities, including attacks with chemical weapons on civilians, and carry on with one’s daily activities? How can societies watch but not in some way respond? In the years to come, when people will be wearing Google Glass, able to share videos of atrocities as they are viewed, the perspective of the online spectator should become even more difficult—there may be a longing for the relative selectiveness of Instagram.

A new, exponentially larger family album is being created. For it to be accessible, not simply an overload of imagery that causes an even greater distancing from events, more coherent ways to filter it will be necessary. Hopefully we can also find numerous practical applications for this abundance of imagery, such as enabling scientists to better study the impact of storms, helping officials to prepare for future catastrophes, and confronting the larger community, including the International Criminal Court, with unconscionable behavior on the part of specific governments.

But the most important question for this “family album” will be to what extent we can enlarge our notion of family. If viewed as happening to the “other,” then much of this imagery—whether joyous or painful—will be ignored by those not directly affected. If, on the other hand, we see ourselves as mutually dependent, both happy for each other’s successes and attentive to each other’s welfare, then even the harshest imagery created by communities of their own distress can serve a purpose.

Fred Ritchin is a professor at NYU and co-director of the Photography & Human Rights program at the Tisch School of the Arts. His newest book, Bending the Frame: Photojournalism, Documentary, and the Citizen, was published by Aperture in 2013.

Rising Waters: Photographs of Sandy is on view at the Museum of the City of New York from Oct. 29, 2013 – March 2, 2014, presented in conjunction with the International Center of Photography.

#SANDY: Seen Through The iPhones of Acclaimed Photographers is available through Daylight from November 2013.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- How Far Trump Would Go

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- Saving Seconds Is Better Than Hours

- Why Your Breakfast Should Start with a Vegetable

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- Welcome to the Golden Age of Ryan Gosling

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com