Photography and commercial oil drilling began and developed at roughly the same time in history. The internal combustion engine existed before both, but it wasn’t until commercial drilling and the production of petroleum had advanced enough to enable their wide spread use in various applications – notably the automobile.

As a child in the early-1970s, I thought gasoline stations were quite mysterious places. To my four year-old mind, the location of each one determined by a naturally occurring pool of oil directly beneath that station. I imagined men discovering the oil, building a gas station, and then sinking long tubes downwards. It was the gas pumps that brought it to the surface – a direct link, flowing without interruption from the earth into my father’s car.

I recently spoke with the writer David Campany about his newest book Gasoline, which explores the notion of how petrol and gasoline stations have been portrayed in photographs from the news.

Jeff Ladd: So, first off David, what is your fascination with Gasoline stations?

David Campany: I’m not sure if it’s gas stations themselves that interest me or pictures of them. Maybe this is because even when you’re using one it can seem like an image.

JL: I think for photographers, since there is a rich history of pictures centered around gasoline stations because of the great images made by Walker Evans, or Robert Adams or Ed Ruscha that people like me are drawn to them (and perhaps even photographing them) although I don’t even own a car. Where have you been collecting the images? From fleamarkets or the Internet?

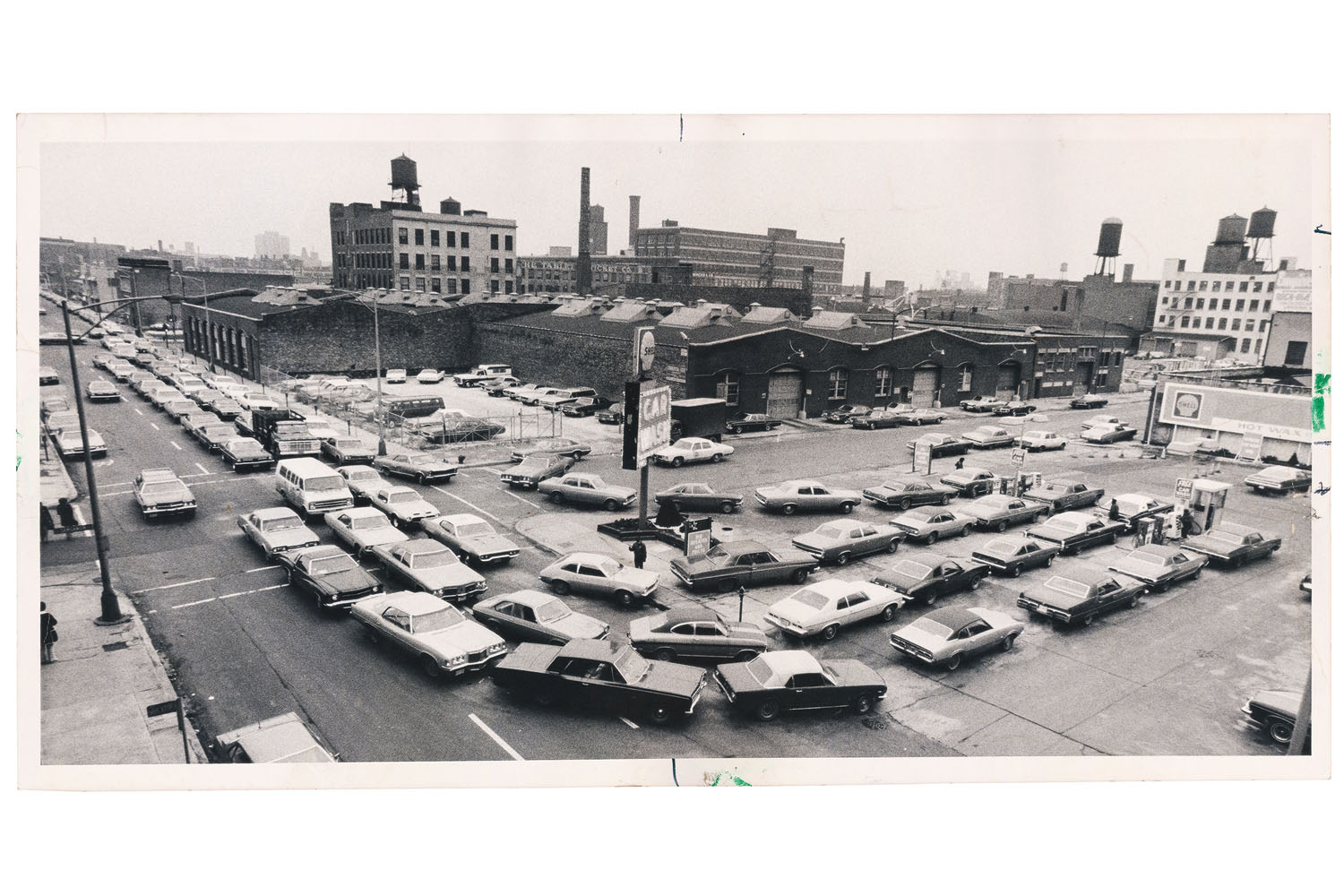

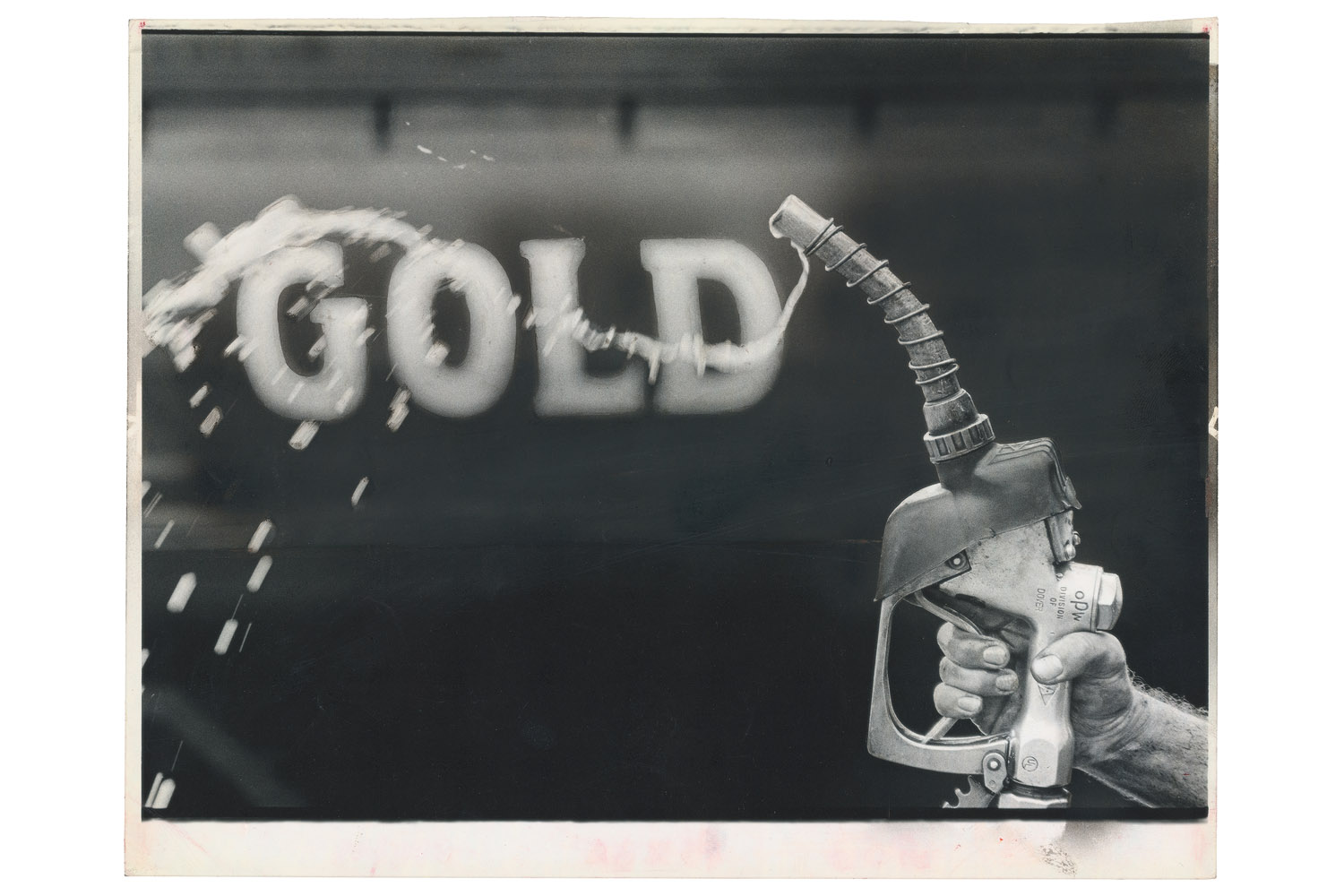

DC: Mainly through the internet. A number of big newspapers have been selling off their archives of physical prints. Most are digitizing their archives so the physical print isn’t necessary to keep. Most that I find are 8 by 10 glossies.

JL: Since many of the images are from the 50s through the 70s, do you see a different language of photography in newspapers being used than what you might find today?

DC: It was very different. The look and feel of old press photography has almost nothing to do with present day press imagery. Not just the aesthetic of black and white prints, but the whole understanding of what a photograph could do was very different. Newspapers had great power, great authority, and I think this affected how press photographers thought of what they were doing, even the most humble ones.

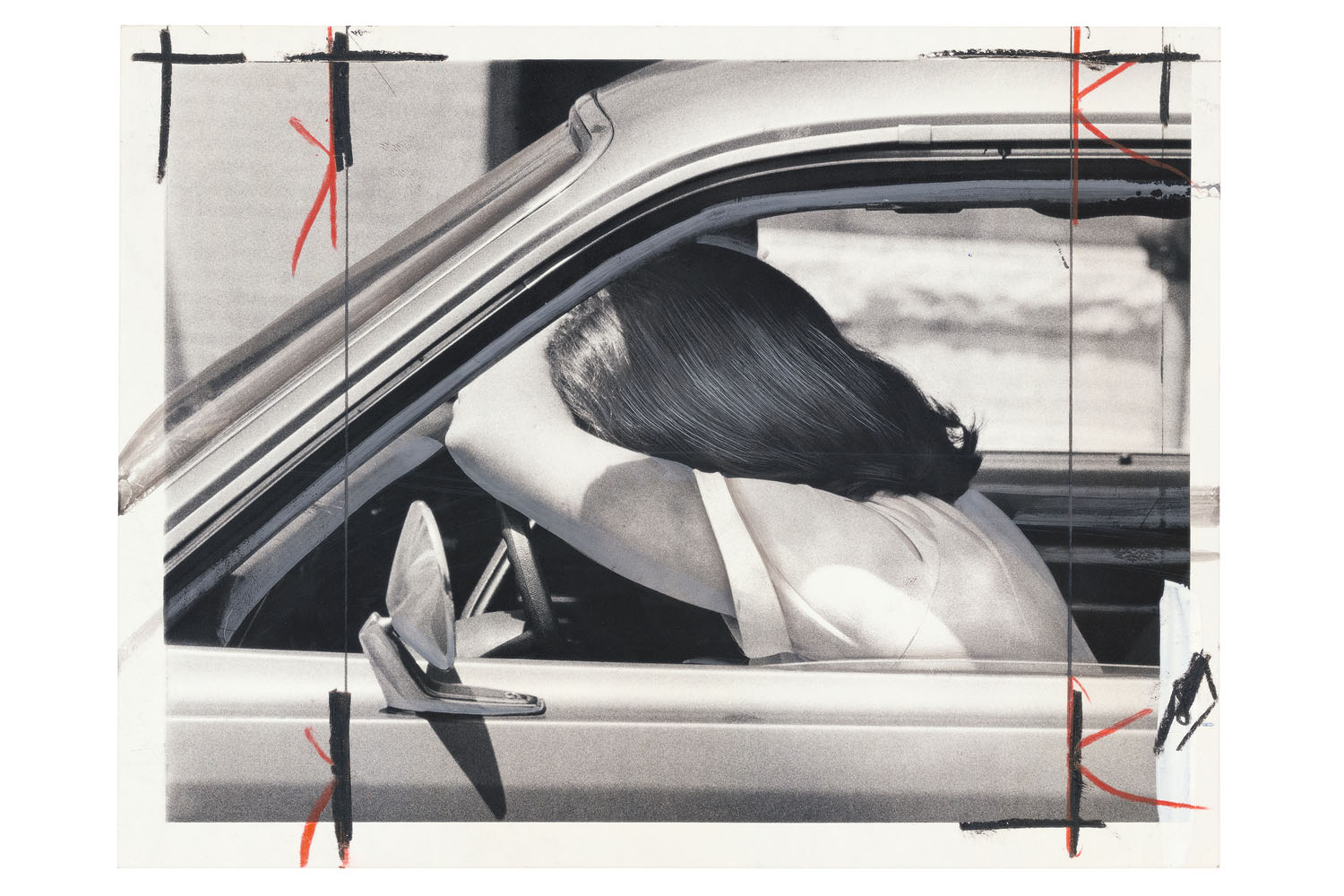

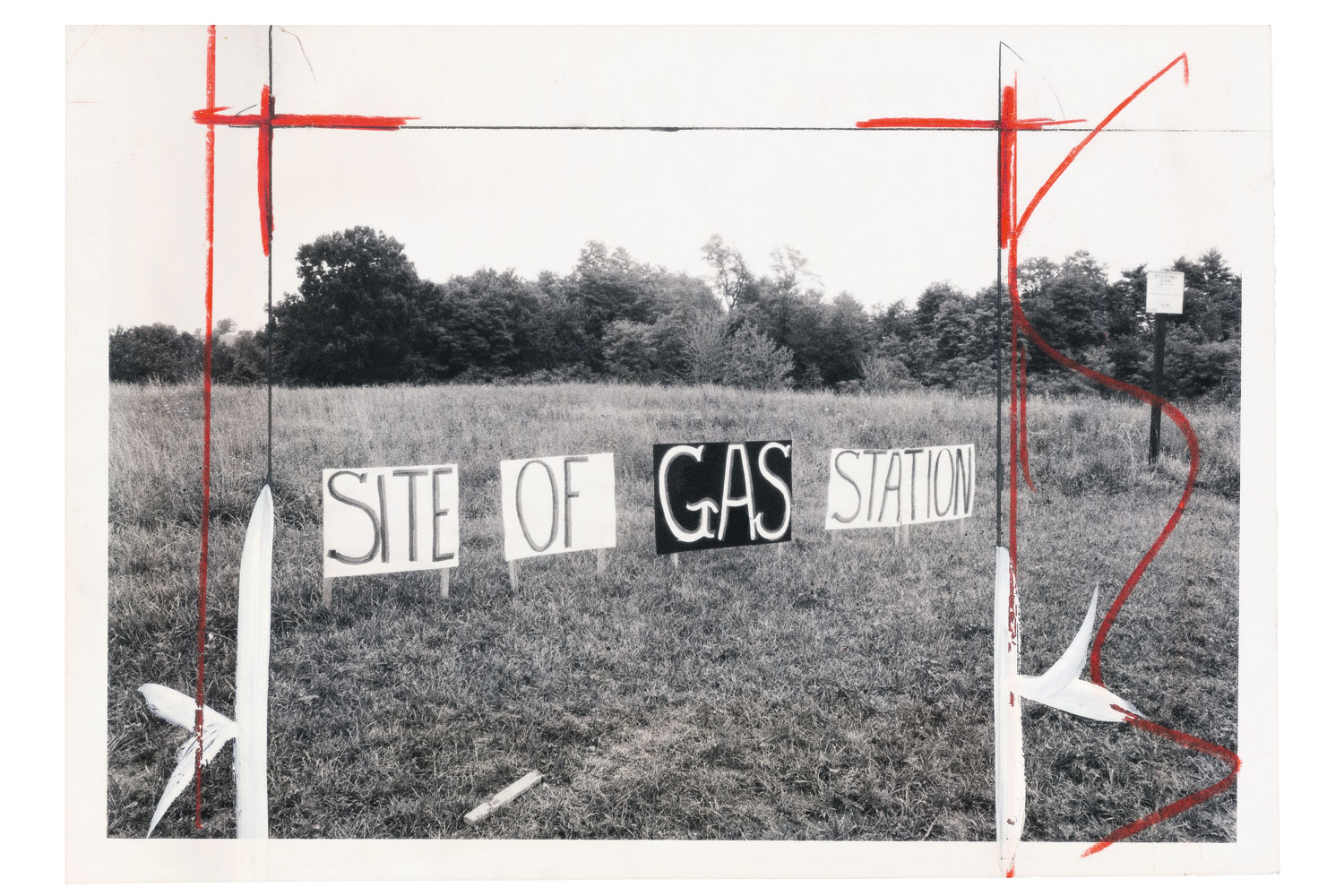

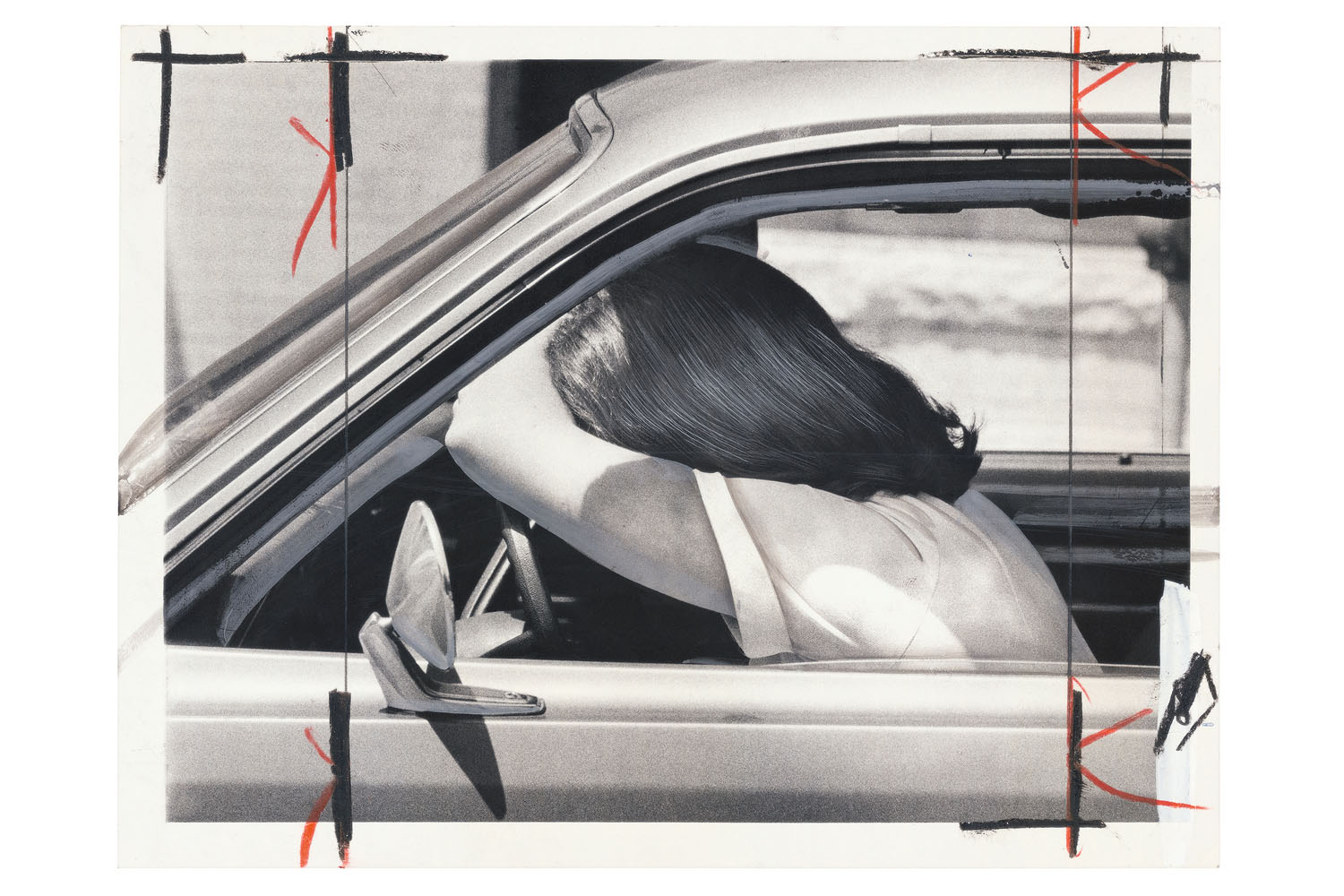

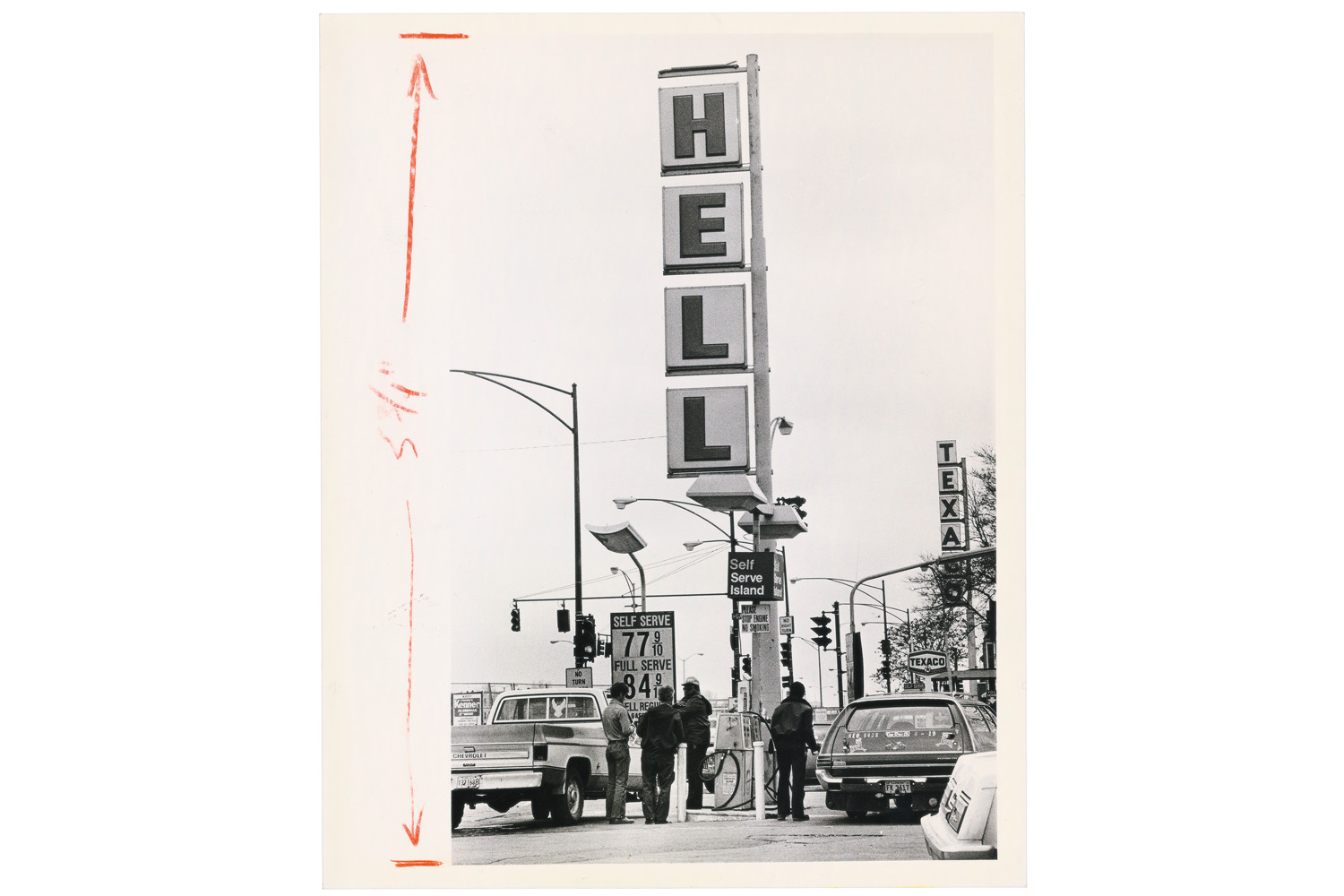

JL: Some of the crop marks, which you have allowed to remain in your reproductions, really reduce the images down to their lowest common denominator. In most of these examples, I certainly think the image is better uncropped.

DC: Yes, very often you see the photographer has a great sense of composition but the cropping that happens is often ruthless, zoning in on the most relevant piece of information in the shot.

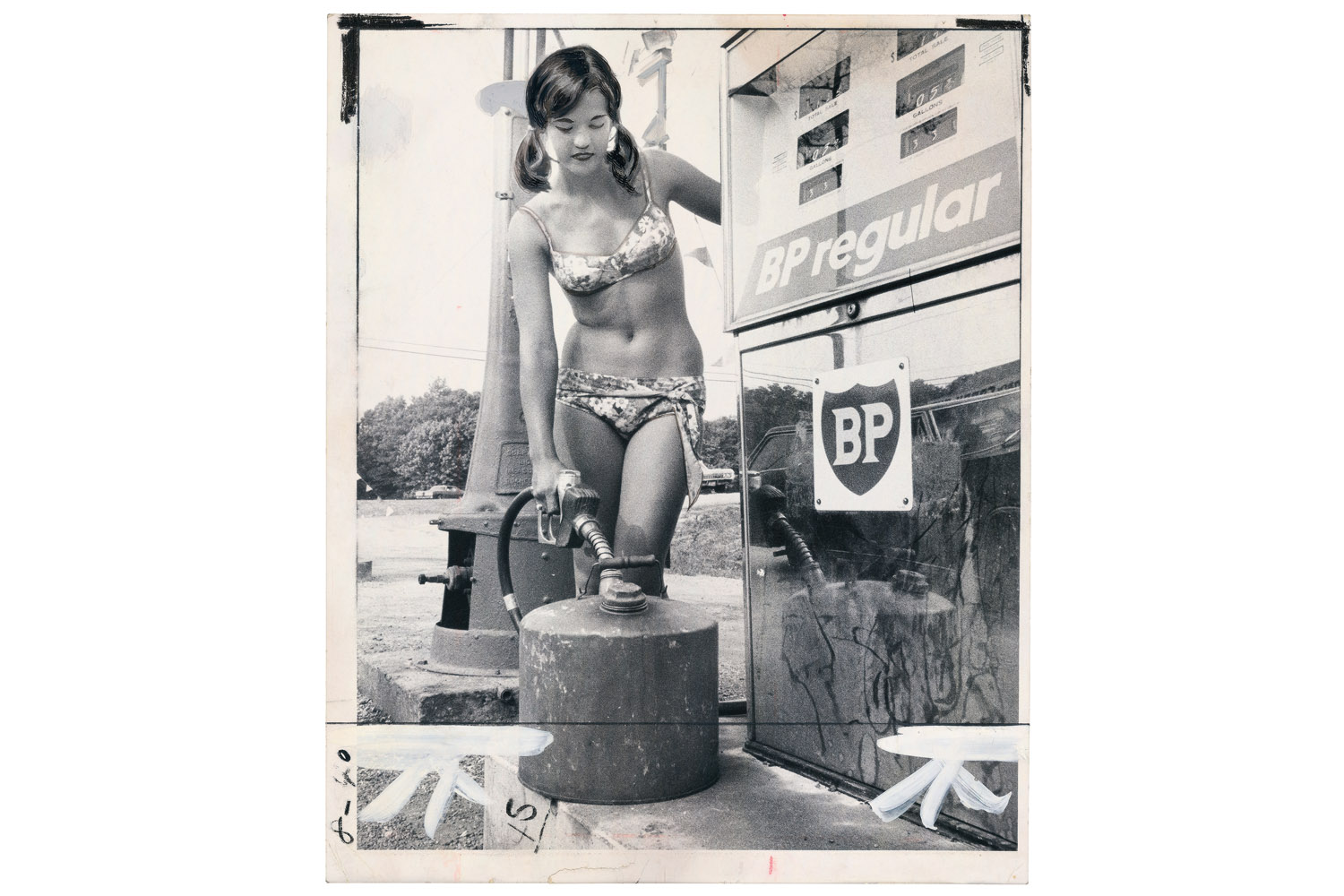

JL: And they are often heavily retouched with white-out and pen. That is something that might be questioned ethically in journalism today.

DC: Many of the photos are retouched by hand, literally painting selectively over the image. This was an art in itself, clarifying areas of the image so that it transferred successfully to the crude halftone print quality of the newspaper. Those skills have all but vanished now, eclipsed by Photoshop.

JL: I found that very interesting. The cover image of your book has a picture of a woman resting her head on a steering wheel. It took me a minute to see that her hair is heavily retouched and details added to what I see is probably just an underexposed negative. Then I saw that the edging of the car window has been accented.

DC: That photograph was the one I found first, and the whole book was an attempt to make sense of that image of a woman waiting in line for gas in Baltimore in 1979. When I first saw it I thought is might be a reproduction of a painting, perhaps by one of those 1970s photo-realists who loved to paint shiny cars. I wanted to build a narrative around the predicament of that woman, but also the predicament of that image, that overpainted press photo thrown onto the rubbish heap of history.

JL: The book is divided into roughly two parts; the first showing the photographs but then the second section of the book shows the backs of each print. This is relevant because they sometimes provide the ‘journalism’ – the who, what, where, why and when of the facts. Why did you feel it was necessary to show the backs too?

DC: The back is like a portable archive for each print, showing the photographer’s name, the newspaper, dates of uses, sometimes clippings from the image’s use in the paper. I like the backs as much as the fronts.

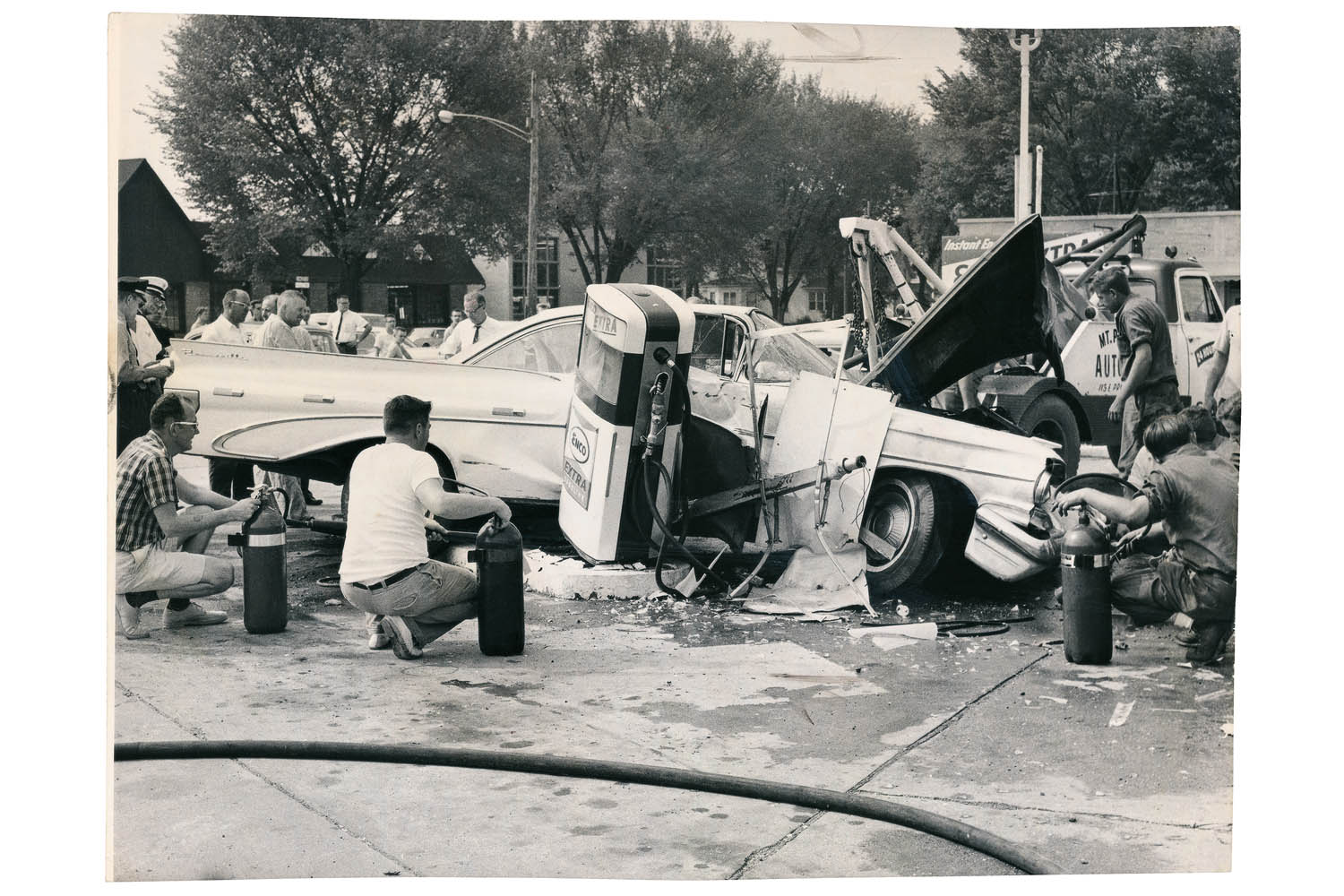

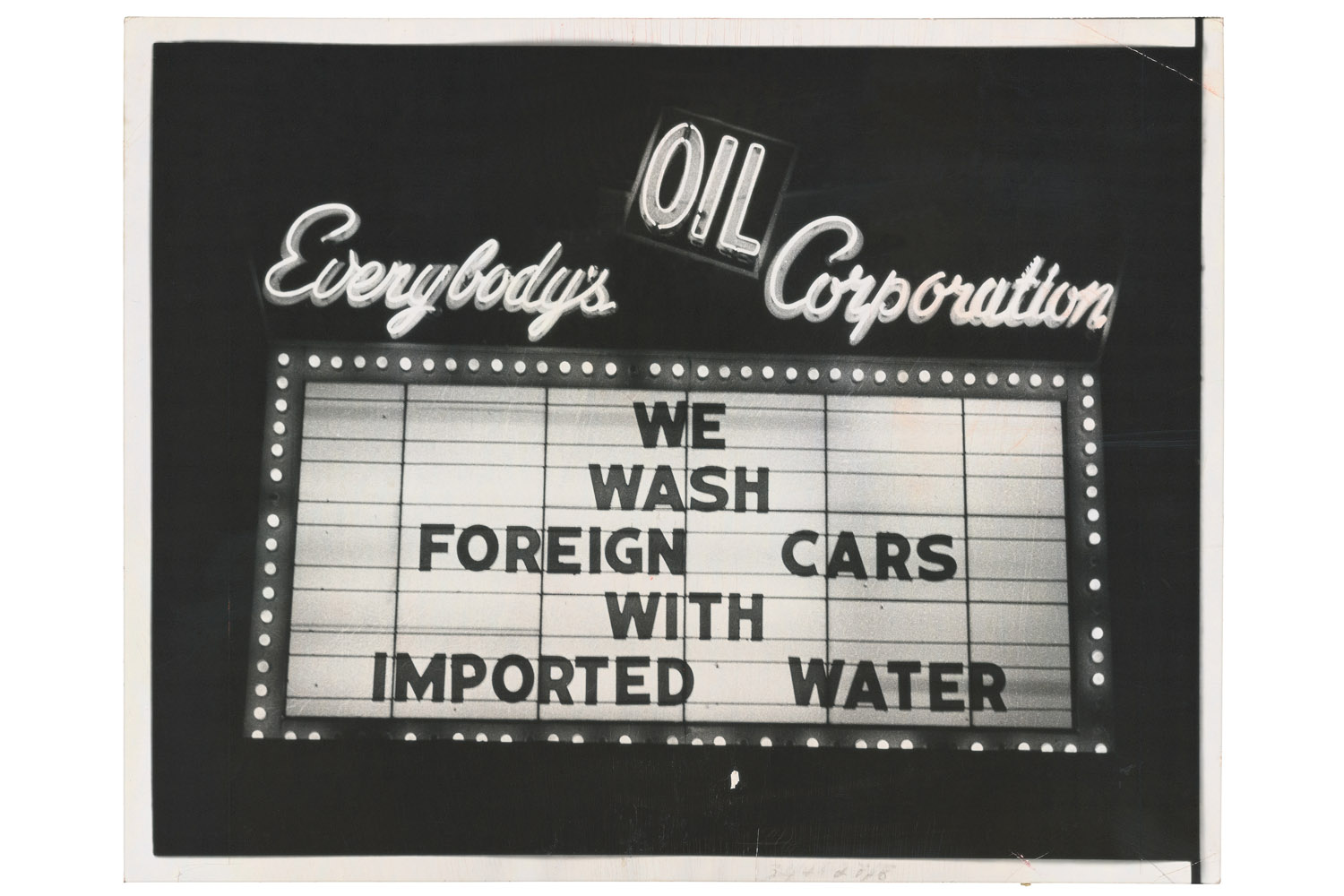

JL: Gasoline stations are a part of everyday life and the politics of oil are very much in the news but the individual stations themselves often aren’t often newsworthy. Your choice of images often shows some disaster relating to a station.

DC: Gas stations are quite banal but when they make news it’s because there’s been a crime, an accident, a price rise or a geopolitical crisis. I think this makes the gas station quite a revealing measure of a society.

David Campany is a London-based writer, curator and artist. Gasoline is available in print from MACK or in a digital edition from MAPP.

Jeffrey Ladd is a photographer, writer, editor and founder of Errata Editions.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- How Far Trump Would Go

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- Saving Seconds Is Better Than Hours

- Why Your Breakfast Should Start with a Vegetable

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- Welcome to the Golden Age of Ryan Gosling

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com