Philip-Lorca diCorcia’s dark and defining series, Hustlers, was shot against a backdrop of devastation and despair during the AIDS pandemic in the late 1980s and early 90s. The work served as a defiant response to (largely) right-wing bigotry targeting the First Amendment rights of homosexuals — specifically, those working in the arts.

In 1989 an exhibition by photographer Andres Serrano (which famously included a photo of a crucifix submerged in the artist’s own urine) stirred controversy and led to attacks on the funding policies of the National Endowment for the Arts. That same year, under mounting pressure from Republican senators Jesse Helms and Al D’Amato, who objected to the explicit homosexuality of Robert Mapplethorpe’s work, the Corcoran Gallery cancelled a planned NEA-funded exhibition of the artist’s work.

Artists who received fellowships from the NEA in 1989, including diCorcia, did so with the proviso that the work they made would not be “obscene.”

DiCorcia, who until this point had conceived of his photos as singular images—intimate, self-contained scenarios of family members and friends in often-mundane situations—embarked on what would become his first cohesive series. With a wholly new premise, he began working with both determination and with a subtle but unwavering strain of subterfuge.

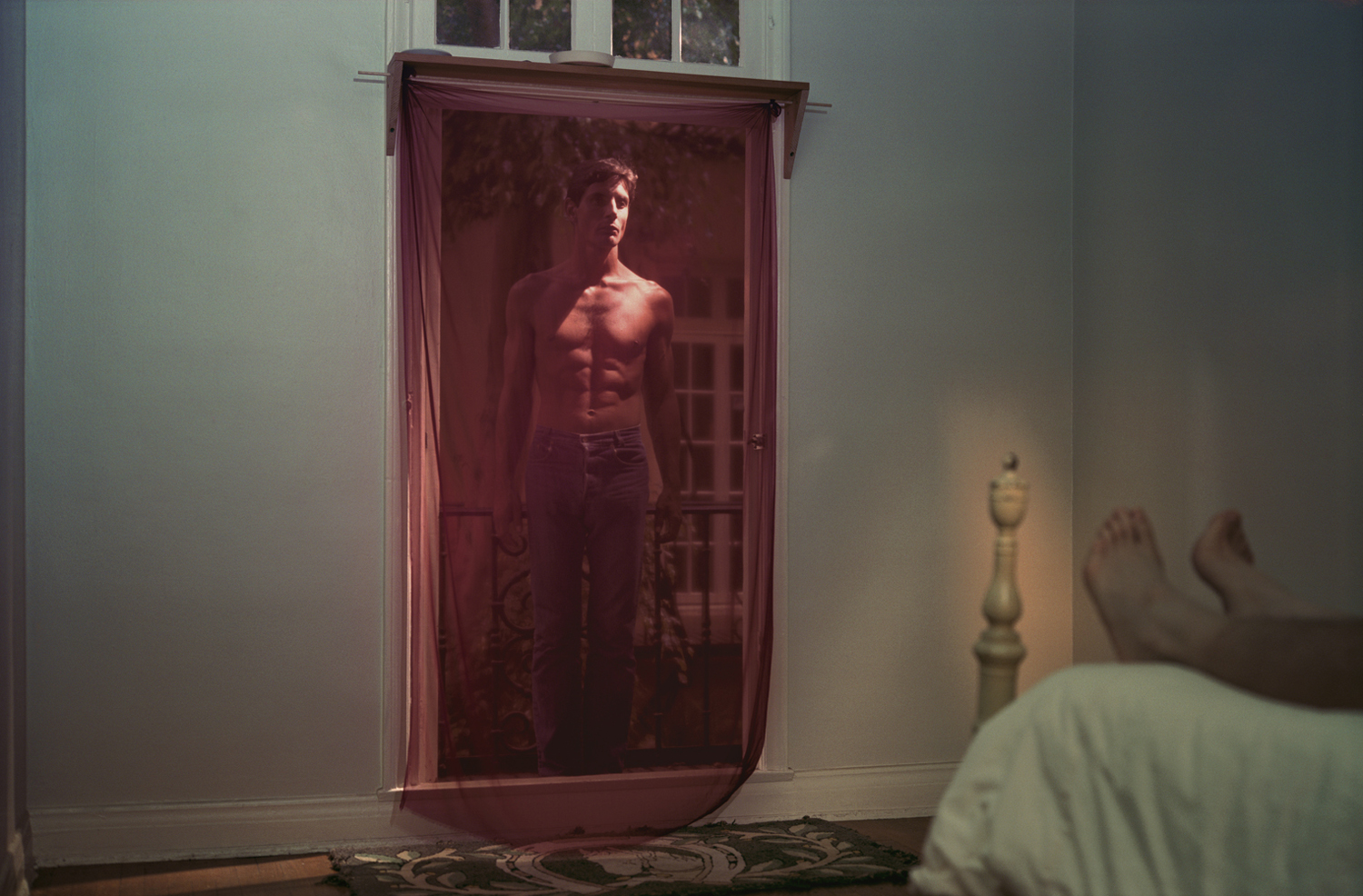

DiCorcia made five trips to Los Angeles, where, with an assistant, he would set up his 6×7 Linhof view camera and lights and run through each potential shot with meticulous detail, before cruising the streets of Santa Monica propositioning hustlers, drug addicts and drifters. He then brought his subjects to his pre-prepared locations to make their portraits and paid them (with NEA funds) the equivalent fee they would have charged for sex.

DiCorcia photographed at dusk, in cheap motel rooms, on street corners, in parking lots and against the neon-lit strip where the hustlers plied their trade. The photographs are titled with the subject’s name, age, place of birth — and the customary price for his services. Masterfully depicting the bleak underside of Hollywood, they also capture the town’s unfulfilled dreams and its fake intimacy.

Crafted as real world dioramas, diCorcia’s images bring to mind film stills, albeit with purposefully open-ended narratives. The photographs are aesthetically seductive, but what sets them apart from mere portraiture is their potent sense of paradox. While diCorcia’s preparation and theatrical direction are more closely aligned to elaborate Hollywood film production than still photography, other aspects of his process — and the authenticity of his subjects — relate directly to the traditions of documentary photography. In melding these seemingly contradictory ideals, diCorcia is able make photographs that MoMA’s former Chief Curator Peter Galassi describes as “operating in the space between postmodern fiction and documentary fact.” In so doing, he challenges the accepted role and involvement of the photographer in the (perhaps quixotic) pursuit of absolute truth.

In 1993, the prints were exhibited in diCorcia’s first museum show, Strangers, at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. The series was hugely influential, not only informing the method and approach to art photography — especially among the photography students at Yale, where diCorcia himself received his masters — but also altering the aesthetics of fashion advertising and editorial portraiture. (Ironically, diCorcia had previously worked for major magazines including Fortune, Esquire and Conde Nast Traveler.)

Over the subsequent two decades, diCorcia has worked as an art photographer and for editorial, fashion and advertising clients. This month SteidlDangin is releasing a new edition of Hustlers, showcasing a comprehensive edit of the photographs, as well as supporting notebooks and Polaroids, while an extensive exhibition fills five rooms of gallery space at David Zwirner in New York through early November.

Despite the thread of melancholy that winds through the Hustlers series, the underlying power of diCorcia’s seminal work stems from the anger — against bigotry, provincialism, self-righteousness — that he channeled while creating these pictures.

In a moving coda, diCorcia shares a personal story in the new edition of Hustlers that puts this work in a somber new light:

“During that period, 1990-1992, the government officially condemned homosexuality,” he writes, “while AIDS made death commonplace. My brother, Max Pestalozzi diCorcia, died of AIDS on October 18, 1988. How much is too much? My brother was very free. I loved him for it. Freedom has its price, and we never know at the onset what the toll will be. He died unnecessarily. I dedicate this book to him.”

Philip-Lorca diCorcia is an American photographer. He lives and works in New York and currently teaches at Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut. Hustlers is available from SteidlDangin from October 2013. The work is on view at David Zwirner Gallery in New York from Sept. 12, 2013 – Nov. 2, 2013.

Phil Bicker is a senior photo editor at TIME.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com