The self is more schismatic than ever before. We have the private, the public, and most recently, the virtual self — our persona represented, in one form or another, on the surface of a screen. The tendency to update the latter continuously has become near compulsive, like a digital tick. From teen celebrities and on-duty police officers to oppressive dictators and everyone in between, few it seems can resist the common urge to snap and share a “selfie.”

The allure of self-portraiture is nothing new, of course. See, for instance, today’s LightBox feature on the mysterious mid-century 6×6 self-portraits of Vivian Maier. The barriers for entry, however, (like artistic ability, or the need for a canvas, an easel, a darkroom, a patron) have all but disappeared. The channels for exhibition or dissemination are far more open, infinitesimal and unpredictable, and greater still is the likelihood that our representations are removed from their original context and forced into another.

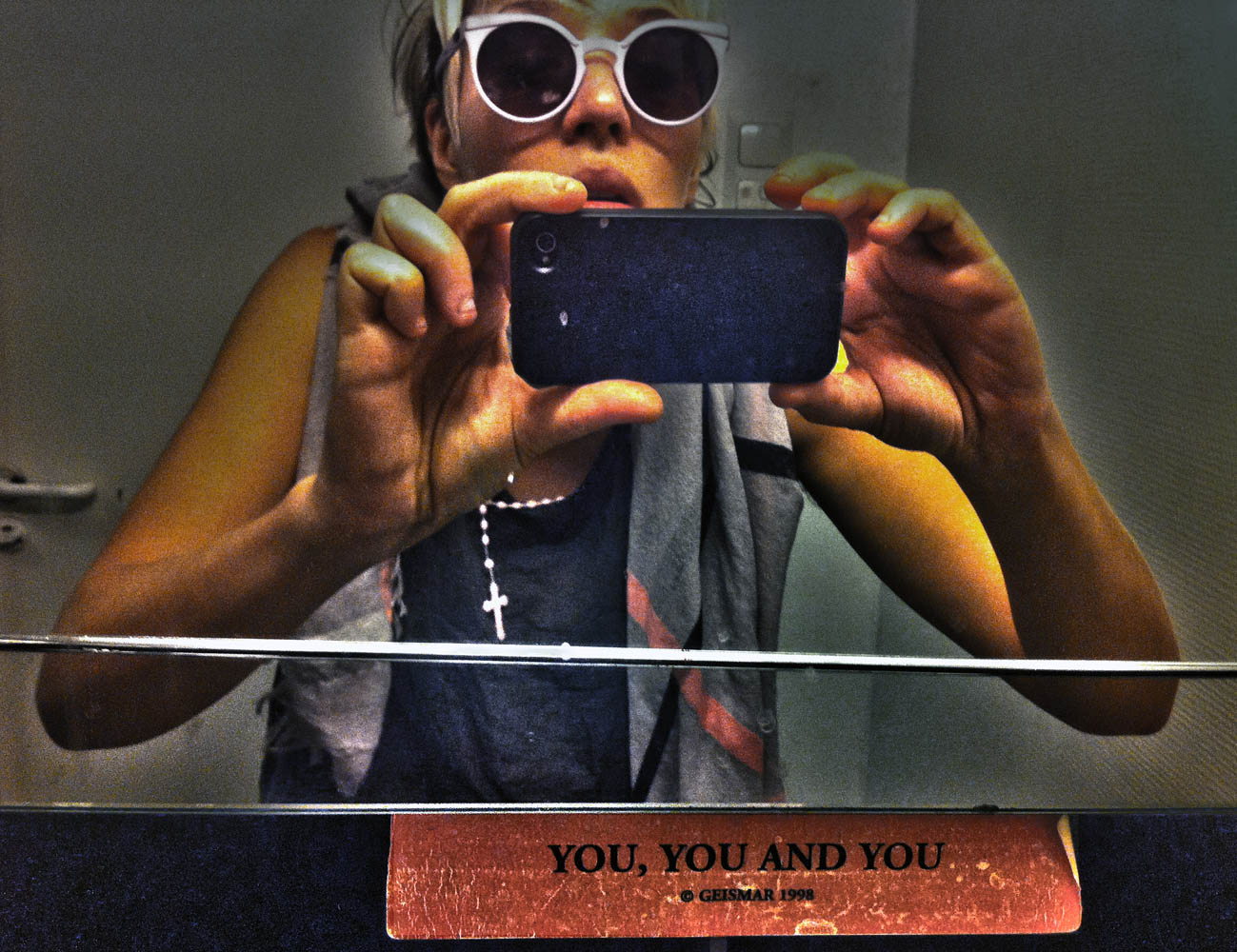

The National #Selfie Portrait Gallery, opening this week at the Moving Image Contemporary Art Fair in London, is one of the first major exhibitions to critically examine this phenomenon of digital expression within a gallery context. The installation features a rotating series of short form video selfies (think Vine or Instagram video) of 19 emerging artists of the millennial generation commissioned by curators Kyle Chayka and Marina Galperina. The duo made headlines earlier this year with their installation at the New York edition of the Moving Image fair, Shortest Video Art Ever $old!, which ushered in the sale of the world’s first ever Vine art, a 6.5-second piece of looping video content created specifically for a then-nascent social media application.

LightBox presents an interview with Chayka and Galperina about their latest curating endeavor and the art of the selfie.

Who are these people in relation to each other and how did you come to select them for the installation?

KC: We decided to include both North American and European artists since the project is in London. I focused on some artists I like who work in new media as well as the field of Internet art.

MG: I’m kind of in love with every artist I focused on. Petra Cortright is the archetypal selfie video artist, totally entrancing. Bunny Rogers’s work is rooted in dark places, places you just don’t go, but you want to because she’s there. Anthony Antonellis came to town and recently got an RFID chip implanted into his hand — it’s readable and contains digital art. I see it as a micro-gallery. A piece by Rollin Leonard, who we also selected, is exhibiting work in Antonellis’ hand right now. That’s commitment. And camaraderie.

What, if anything, elevates an ordinary selfie into the realm of art?

KC: I think it’s any selfie that challenges the idea of selfies as a medium — it has to be self-critical! That often seems to take the form of humor.

MG: Most selfies are boring and unmoving because most people are boring and unmoving. People who are good writers send well-written texts, right? I feel like the selfie is like that — a very common medium of communication or catharsis — and a visual artist, especially one that spends so much time working digitally and living online, is just better at communicating something more than themselves with it.

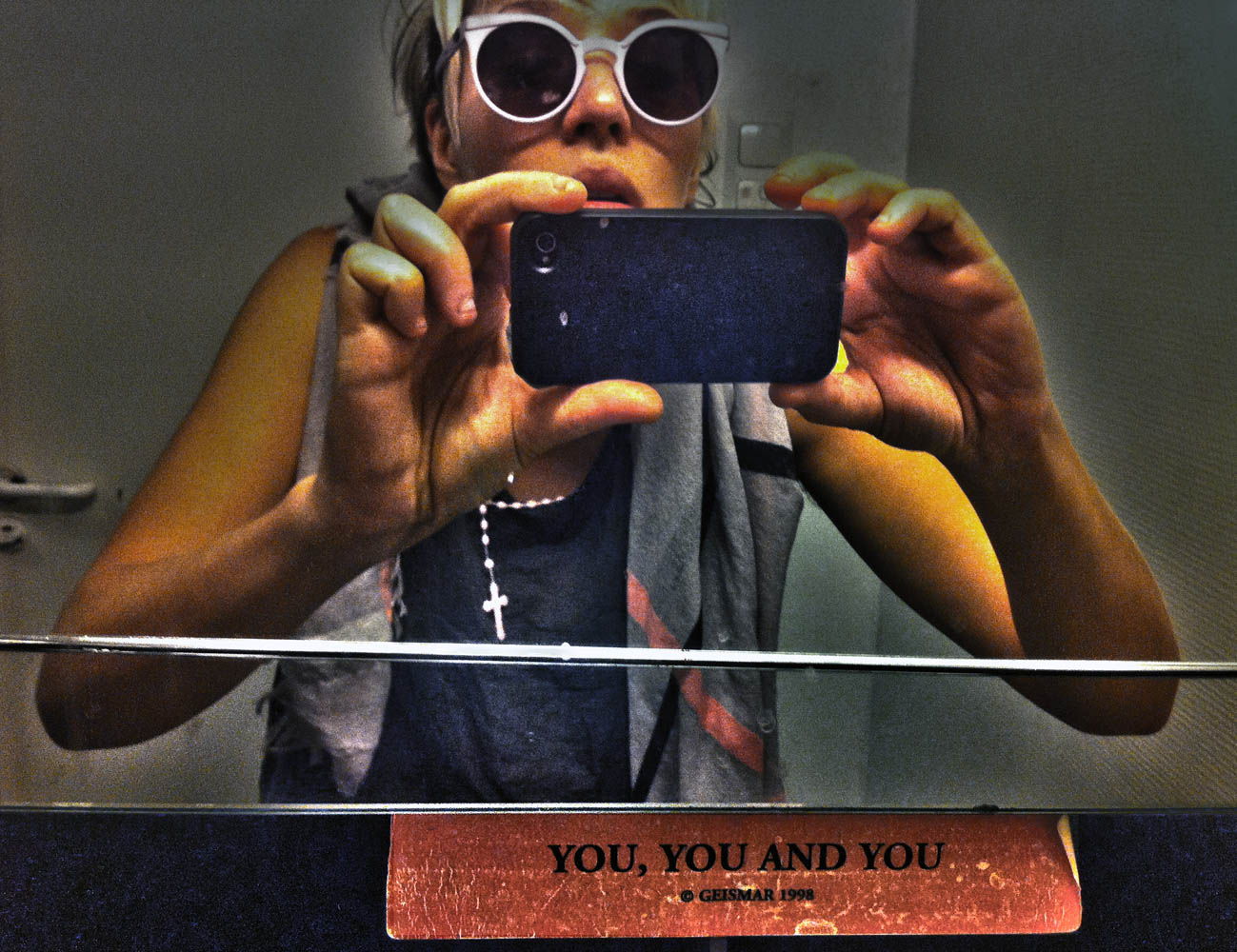

Can you talk a bit about some of the more common tropes or conventions you’ve come across in selfie-portrature?

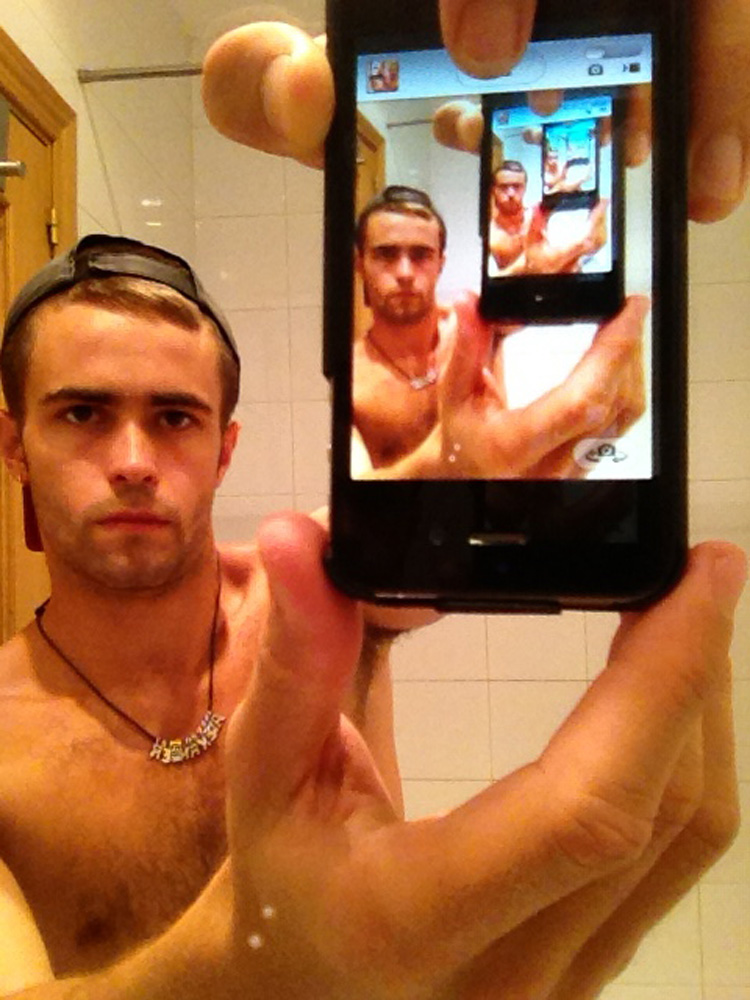

KC: There’s the extended arm in the corner of the frame, the repeated angle that shows off your best side, a particular expression…

MG: It’s a tense, closed loop. The selfie-er is revealing or performing a deliberate image of themselves. The audience knows that they are. They know that the audience knows that they are, and so on.

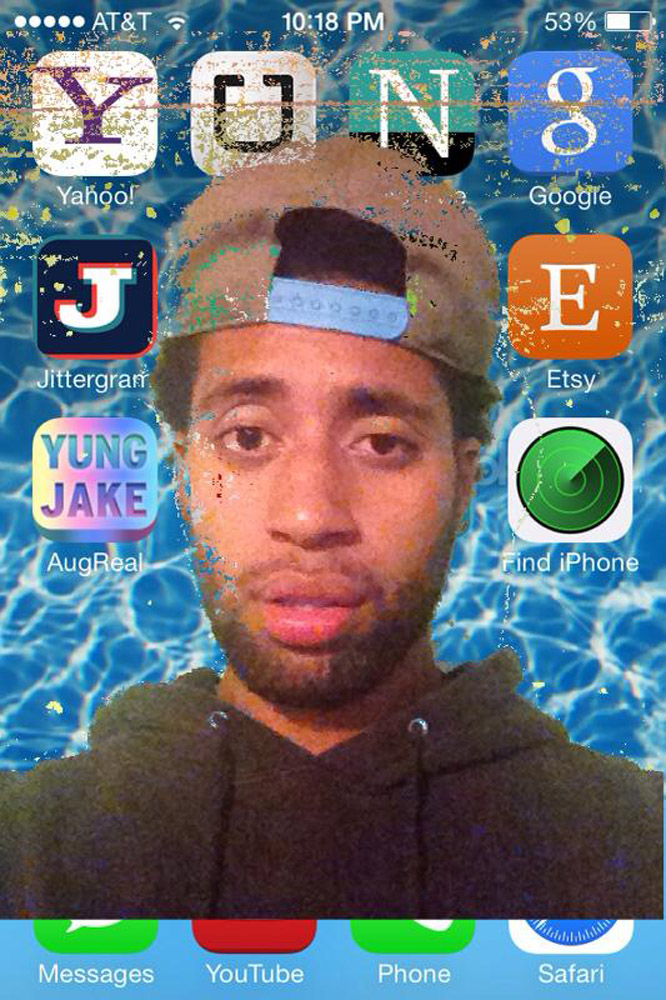

What kind of tradition does the selfie come out of? Is there a difference between a selfie and what we’ve come to know as a self-portrait?

KC: I think the selfie departs from self portraiture in that the format is improvised and fast, where most self-portraiture of the past takes the form of laborious paintings. I think smartphone selfies come out of the same impulse as Rembrandt’s though — to make yourself look awesome.

MG: Yes, and it’s increasingly self-aware. The constant pressure for digital self-branding took the age-old self-portraiture tradition and put it into hyper-drive. The technology democratized it. It’s less about narcissism — narcissism is so lonely! — and it’s more about being your own digital avatar.

Why have you chosen to focus this installation on short form videos instead of just stills?

KC: Artists aren’t often given the opportunity to work in video in an approachable way; we want to encourage more artists to work in this format. We also want to push the boundary of digital collecting by selling short video work.

MG: I think it reflects the current social trends more. And there’s more at stake. Intimacy on the internet is contentious — people are worshiped and bullied, loved and attacked — all based on a series of short, tight performances. It’s unnerving. I love it.

Tell us about your previous installation, Shortest Video Art Ever $old! How might have that lead you into this current project?

KC: For the last project, we commissioned a series of Vines because the format was new and exciting. Plus, we posed the project as a way to sell digital artwork in an affordable format. For London, we’re still pushing the short video as an artistic medium, but limiting ourselves to one particular subject to produce a comprehensive investigation of the idea of the selfie.

MG: Recently, there has been so much knee-jerk talk about “millennials” and “their internets” and “their selfies” by angry people projecting misconceptions of the youth — as well as tons of reasonable scientific and social research on how this constant live-casting of our daily existence is affecting us. So, we knew what we wanted to plop down in a middle of a serious, incredible fair, since we were lucky to be invited back. This is in no way the first selfie art show. There have been many. But, this is high-profile enough to attract the angry people — come at us, bros! — and to see how our favorite artists would operate within these formal constraints, under the weight of these associations.

Can you talk a bit about the community who collects this emerging artform? How does that work?

KC: We come up with original contracts for each project. During SVAES, the collector was given the ability to be the first person to put the art online. We’re hoping that more collectors catch on — digital art is a burgeoning field, but it lacks a developed support infrastructure.

MG: We both own work from the artists in this show and a few of them have been in the first digital art auction at Phillips very recently. There are major moves and big-figure being made this year, but we’re also very much in favor of a micro-community of collectors and artists buying art — not like some luxury piece of furniture, but pieces of the artist, stakes in their new media and digital practice. It’s a community that supports, collaborates with and grows itself. We want people to buy art that they can share with the world instead of hoarding behind a curtain of a private salon.

Kyle Chayka and Marina Galperina are curators and writers based in Brooklyn. The National #Selfie Portrait Gallery is on view at the Moving Image Contemporary Art Fair in London Oct. 17 – Oct. 20, 2013. Contribute to the discussion by taking your own Instagram or Vine selfies and tagging them #NationalSelfiePortraitGallery.

Eugene Reznik is a Brooklyn-based photographer and writer. Follow him on Twitter @eugene_reznik.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com