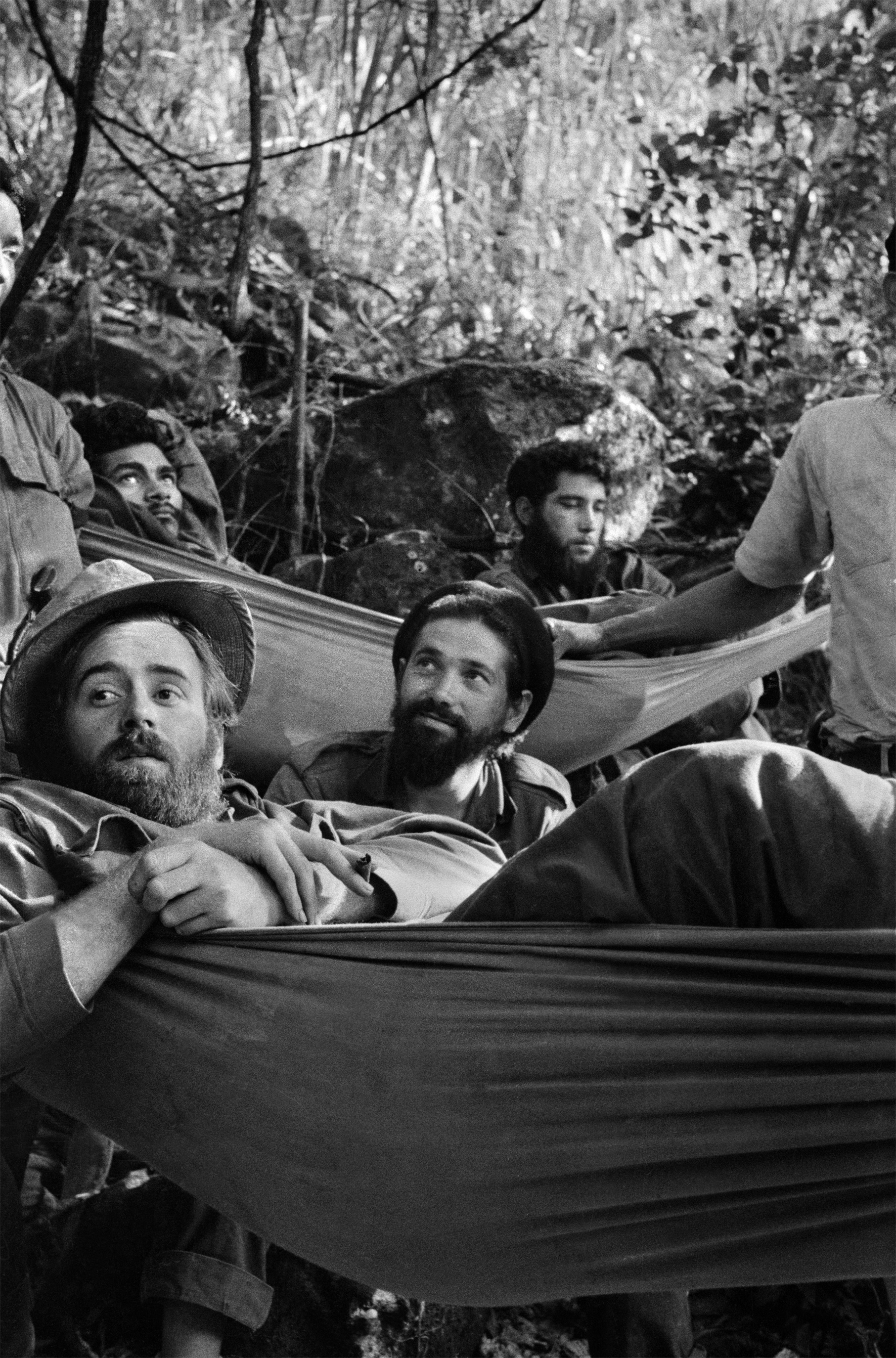

The image on the April 19, 1958 cover of Paris Match is surely among its most significant, and is certainly among its most storied. Editors at the magazine, which at the time was headed up by Hervé Mille, had decided to run with an unsettling photo: Pictured was a bearded, bespectacled gunman in combat fatigues; holding his arm high, he is shown aiming a pistol out of shot while a dense cluster of trees frames his figure. The setting, readers quickly learned, was the Sierra Maestra mountains of Cuba. And the man? “Fidel Castro,” a subhead further explained, “the Robin Hood of the Sierra.”

While it might seem a jarring description today, particularly for a figure who would become so infamous; Castro, and the rebellion he and Che Guevara had by then headed up for six years, were virtually unknown to many in Europe. Indeed, to some readers, the explanation might have made sense: this figure seemed like some sort of French maquisard, a guerilla fighter maybe hoping to take from longtime Cuban dictator Fulgencio Batista, and give to the common people. The magazine cover – which formed part of a larger photoessay – was to be the first ever in-depth look at the Cuban revolution, and having Castro on the cover turned out to be a quite a scoop for Match.

But of course scoops don’t come easy. The essay – shot in 1957 and 1958 – was the work of a Madrid-born photographer who had taken many risks to get the images out. His name was Enrique Meneses, and he was as passionate about journalism as he was eager to find stories. At that time, he was something of an unknown internationally, but he was nimble with a lens, and had a knack for being in the right place at the right time.

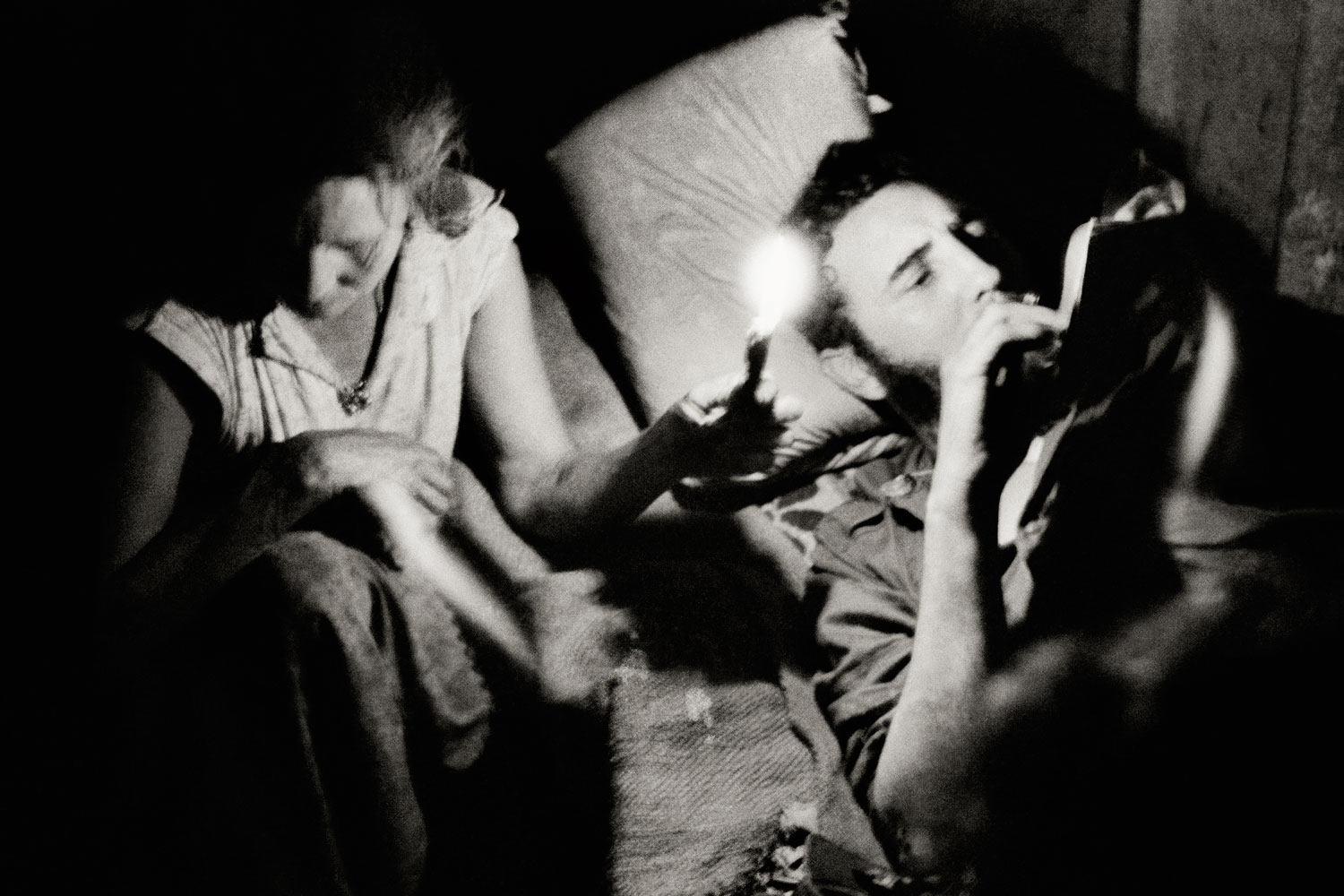

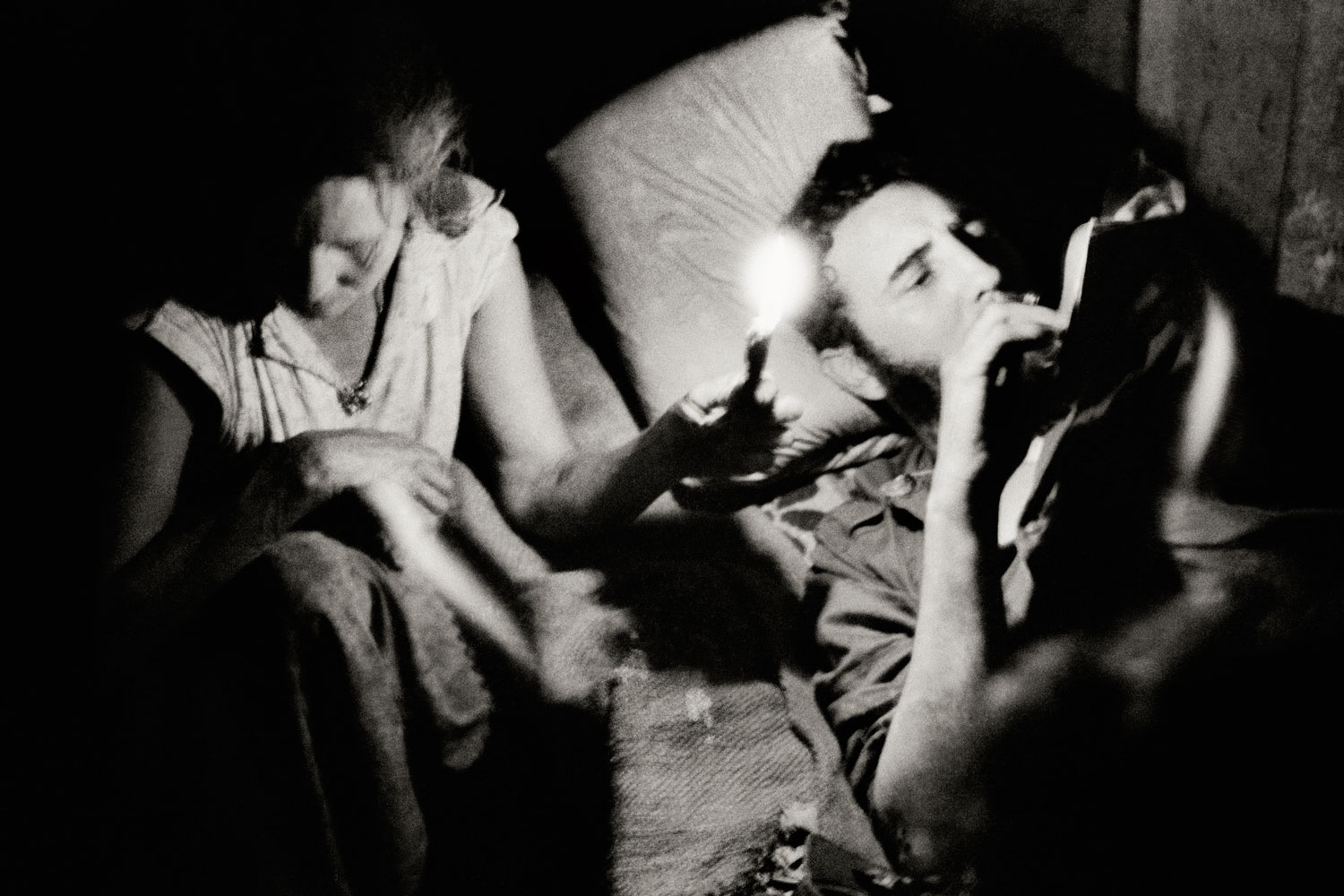

Menses had been sent to a Cuba languishing under the heavy rule of Batista. On landing in regime spy riddled Havana, the Spaniard spent weeks trying to get in touch with the revolutionaries, who were based in the foothills of the Sierra Maestra mountains. Through chance encounters, he eventually found someone to take him to the rebel-occupied area. But gaining access was only the beginning. After spending a month shooting, he had to find a way to get the images back to his editors. His contacts put him in touch with a sympathetic young woman, who smuggled his film out of Cuba to Miami in a petticoat, from where they were sent to Europe. And there was more: When the essay was finally published, the Cuban police arrested and beat Meneses. But it didn’t deter him. The essay marked just one high point in a career filled with well-regarded work, which only came to an end with his death in 2013.

Born to a Spanish family who had relocated to Paris, his father, Enrique Meneses Sr., was publisher of Cosmopolis magazine. Meneses the younger had journalism in his veins from the start, and having come of age in Franco-ruled Spain, was eager to escape its grip.

“He was restless, curious and cosmopolitan,” says Gumersindo LaFuente, a Madrid-based journalist and contributor to Enrique Menses: A Reporter’s Life (La Fábrica 2013). “This led him out of Spain, which was closed in on itself.”

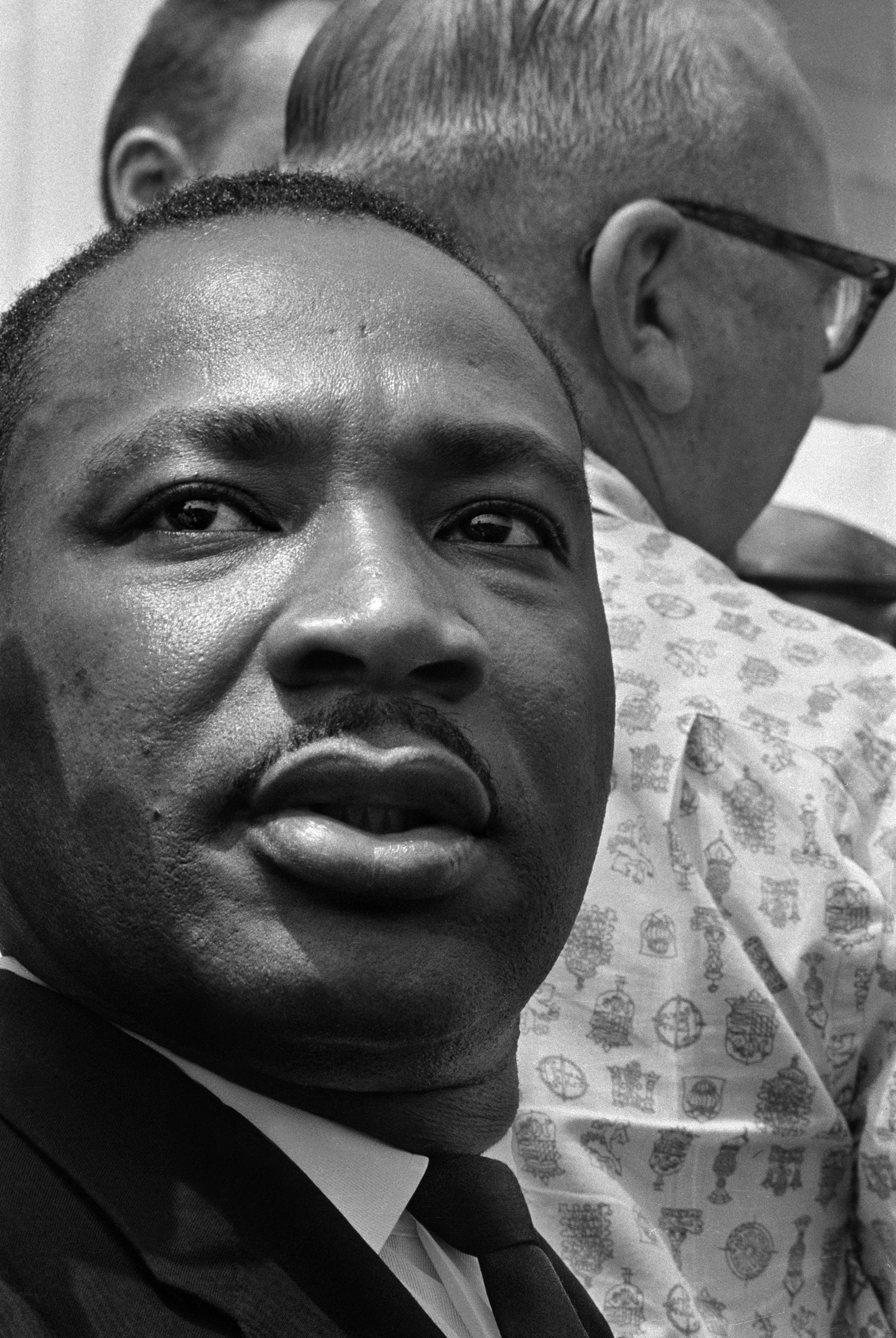

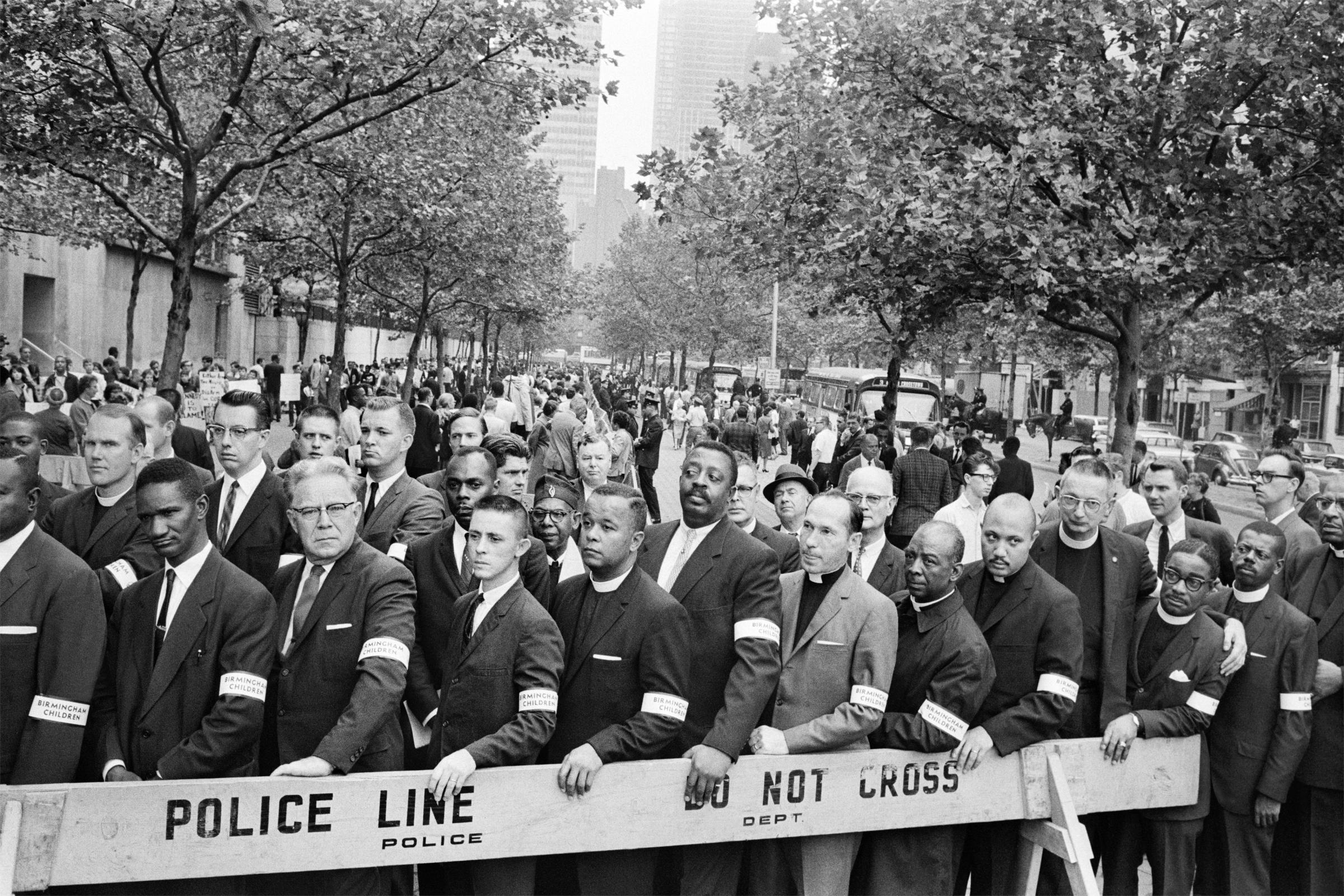

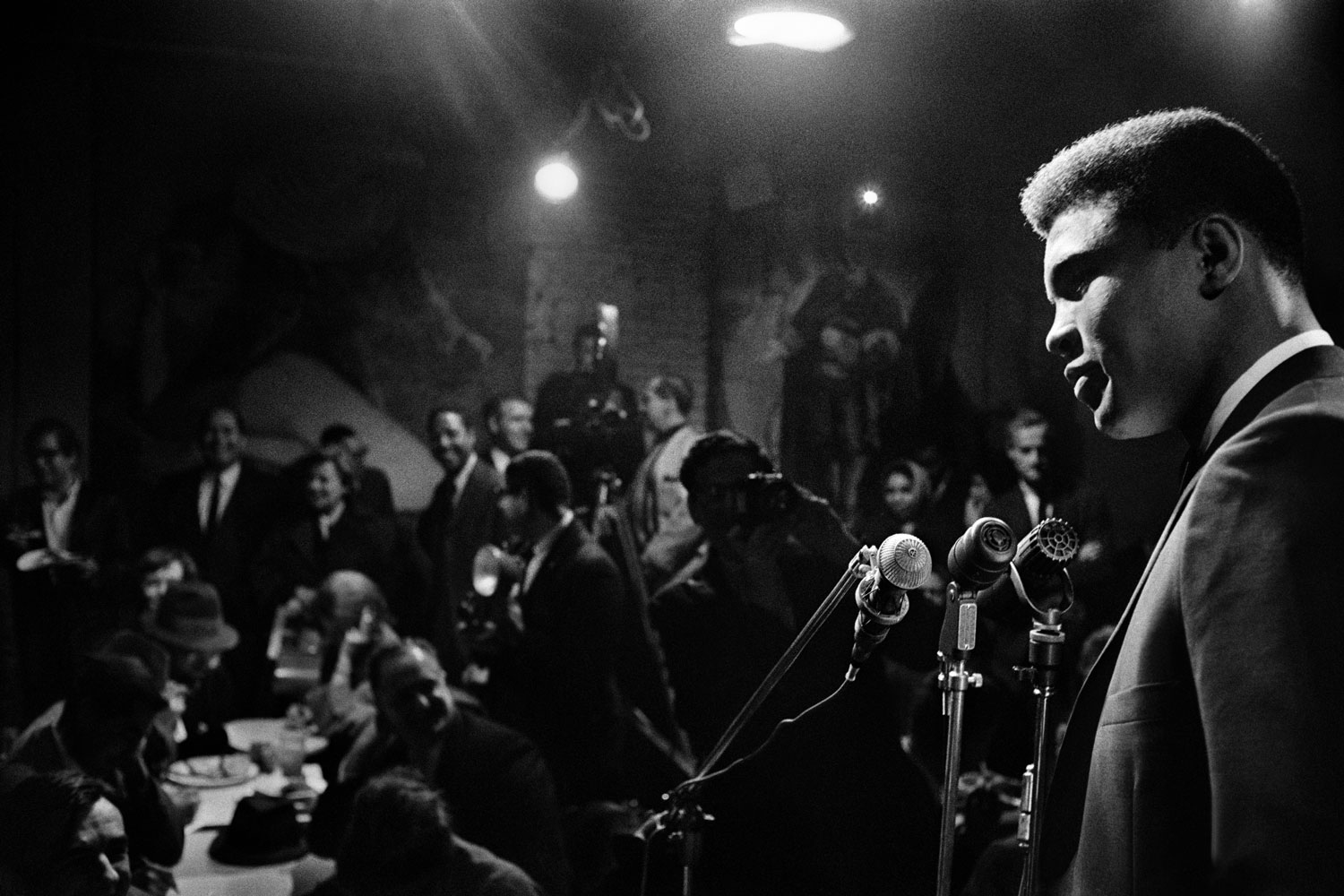

And if his country was looking inward, he looked outward. Throughout his career, he covered everything from the March on Washington – where he produced memorable images of Martin Luther King – to the Seuz Crisis, and from conflicts in Zimbabwe (then Rhodesia) to Angola. He pictured politicians, socialites, artists, protestors and royals, and his work featured regularly in LIFE, and the New York Times.

Meneses’ style was a sort of non-style: he rarely used a flash or telephoto lens, and tended to keep his framing simple. An empiricist to to the last, he was a true self-trained documentarian, his camera a conveyor of what he found, not what he wanted to see. His vocation was life itself.

“Journalism is about going, hearing, seeing, coming back and telling someone,” Meneses said in a 2012 interview with Babylon Magazine, “The University of Journalism is the streets.”

Enrique Meneses: A Reporter’s Life was published Sept. 30, 2013 by La Fábrica.

Richard Conway is Reporter/Producer for TIME LightBox. Follow him on twitter @RichardJConway. He has previously written for LightBox on Erwin Olaf, Gary Winogrand, Ezra Stoller and Peter Hujar.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com