When I visited the Ivanpah Solar Electric Generating System, which sits in the Mojave Desert on the border between California and Nevada, I had to be careful where I looked. The engineers warned me not to look directly at the receivers arrayed on top of the centralized solar towers, which collected the desert sunlight concentrated by thousands of mirrors on the desert floor. The solar receiver was as bright as the heart of the sun, glowing with a retina-melting white. I had to force myself to look away.

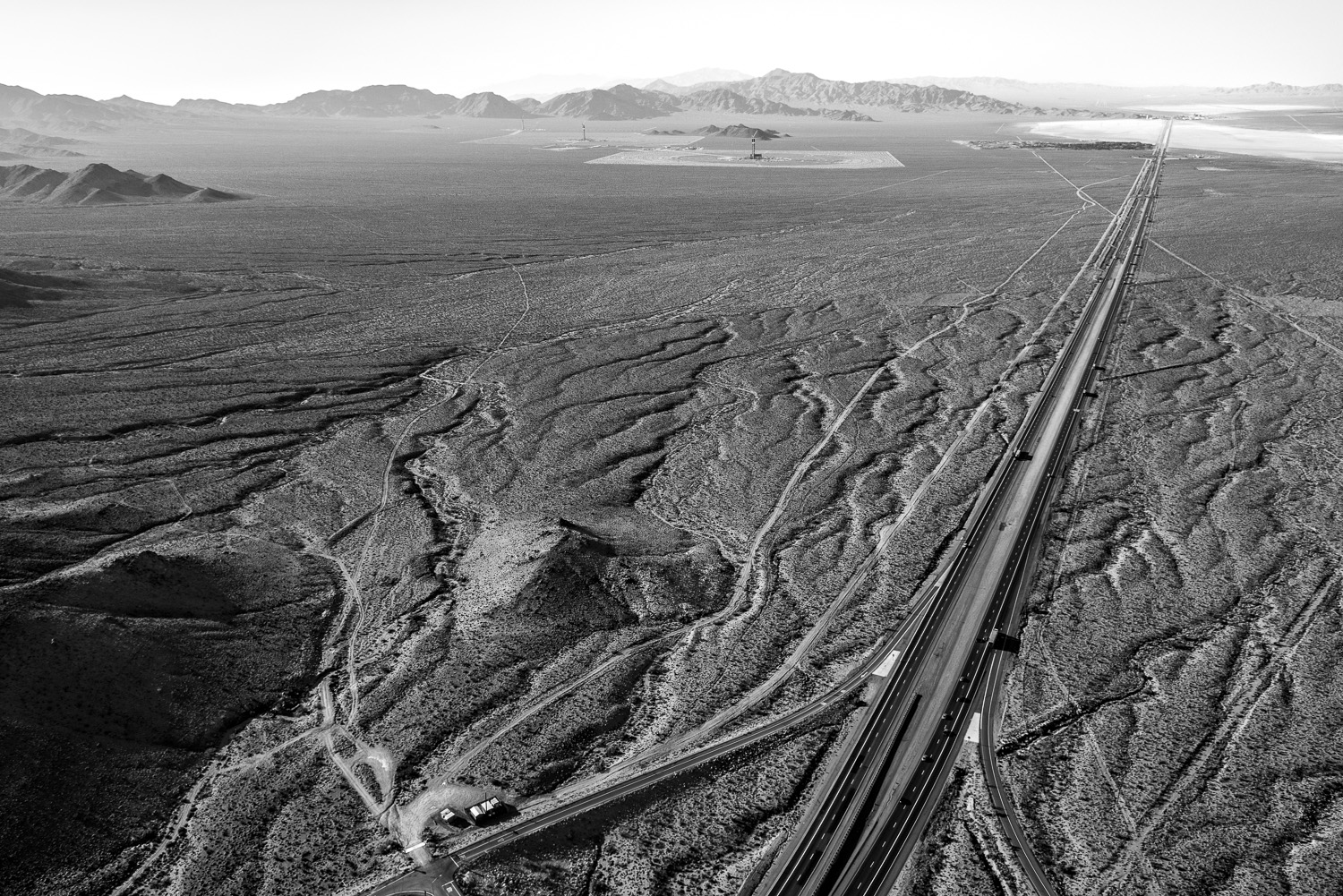

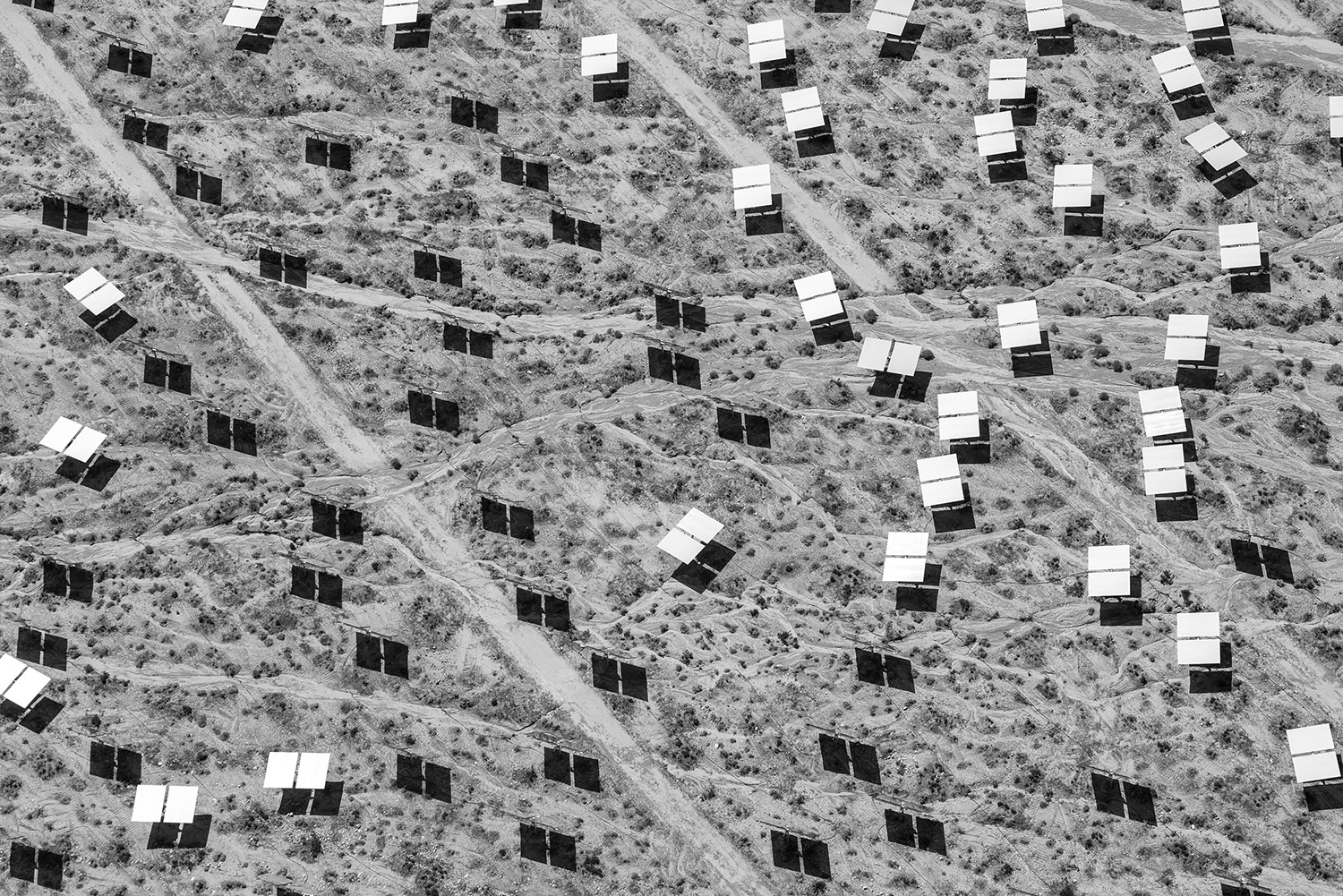

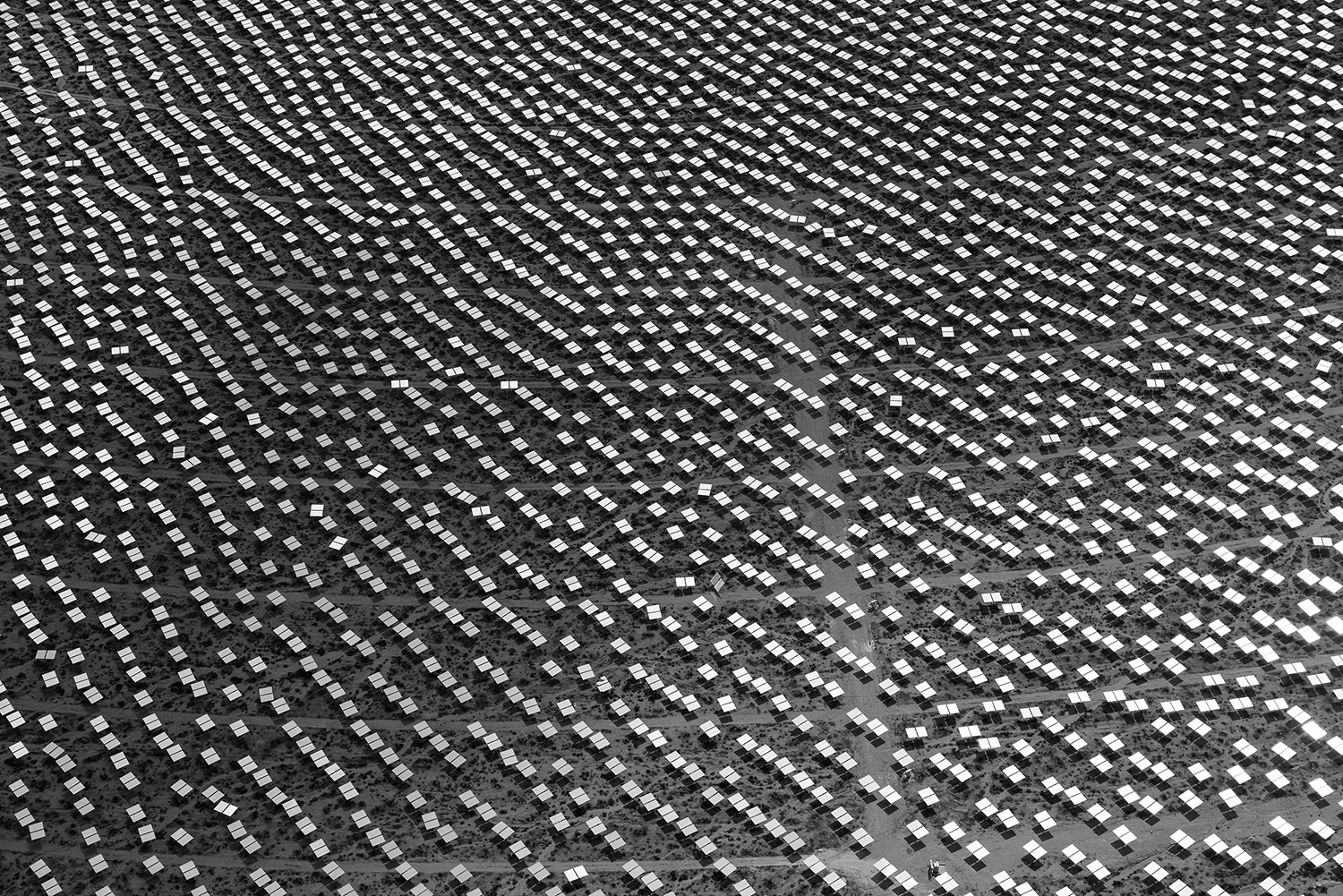

Jamey Stillings, though, has far better eyes than I do. A photographer known for his work capturing mega-scale projects like the new bridge at the Hoover Dam, Stillings has been tracking the construction of Ivanpah since 2010, when he began an aerial survey of the site. His epic black-and-white images of Ivanpah reveal how different this solar plant is from other major infrastructure projects. Unlike solar photovoltaic plants, which generate electricity directly from sunlight, Ivanpah uses hundreds of thousands of curved mirrors to reflect and concentrate the desert sunshine. Three tall solar towers, each ringed by the mirrors, collect the heat and generate steam, which drives electric turbines. When it finally opens later this year, it will be the biggest solar thermal plant in the world.

Heat becomes steam becomes electricity—in the most basic sense, Ivanpah is no different than any fossil fuel plant burning coal or natural gas to generate electricity. But there are no emissions aside from the drift of water vapor, and where a power plant is all hard edges and forbidding steel, Ivanpah seems almost soft, integrated into the desert, as Stillings’ photos show. Even if it didn’t generate enough electricity to power 140,000 homes, Ivanpah would be one hell of a piece of landscape art.

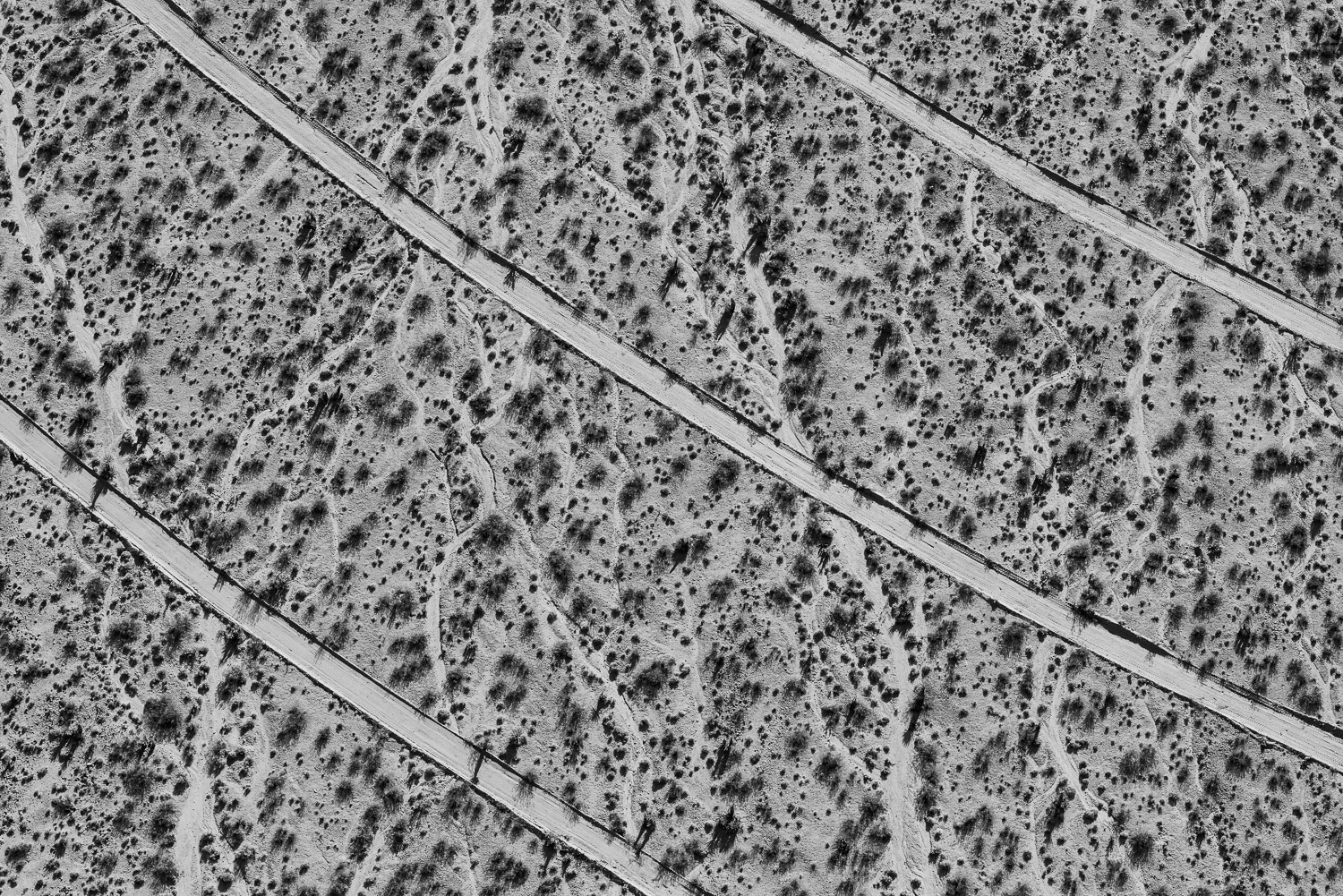

But Ivanpah’s construction was not without controversy. The desert may seem lifeless from afar, but the Mojave is home to countless species, including a threatened desert tortoise that nearly scuttled the entire project. (In the end, the tortoises were painstakingly—and expensively—moved away from the footprint of the plant.) As Stillings writes, Ivanpah “raises challenging questions about land and resource use.” Environmentalism is supposed to have a preference for the small and the simple—and Ivanpah is neither, sprawling across 4,000 acres of public land that had once been largely undisturbed. Stillings’ pictures show the story—what was once nature has been forever changed.

Yet if the alternative energy movement is to ever make a true mark, Ivanpah may provide exactly what it needs: scale. As Stillings’ images illustrate, Ivanpah is nothing if not big, a dream of a different way of powering society that is suddenly, radically here. We may look back upon the Ivanpah Solar Electric Generating System as the beginning of a new era, one where industrial projects that rival the Hoover Dam for scale are integrated with the Earth, not a blight on it. And Jamey Stillings will be there to document it.

Jamey Stillings is a photographer based in Santa Fe.

Bryan Walsh is a senior editor for TIME International & an environmental writer. Follow him on Twitter @bryanrwalsh.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com