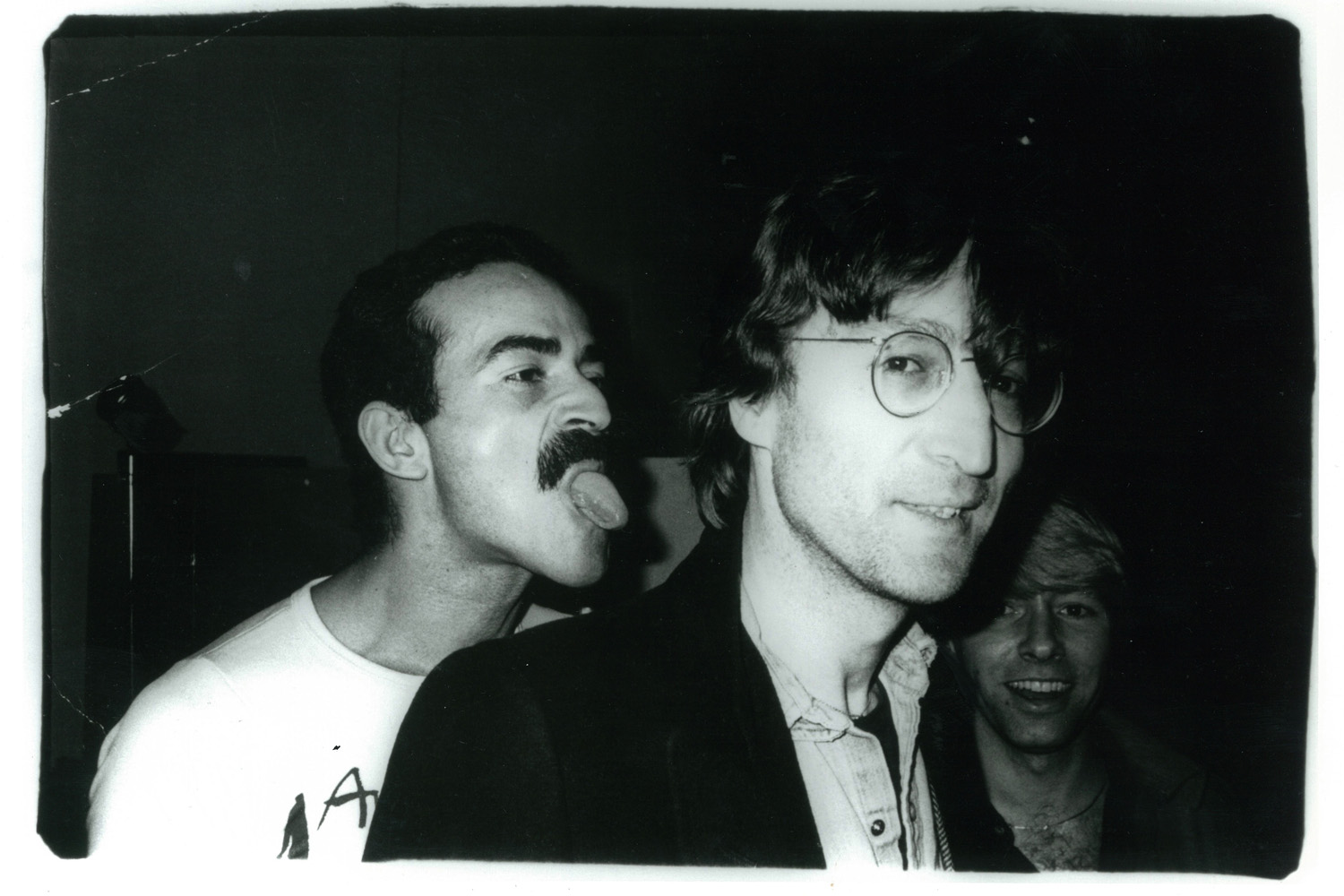

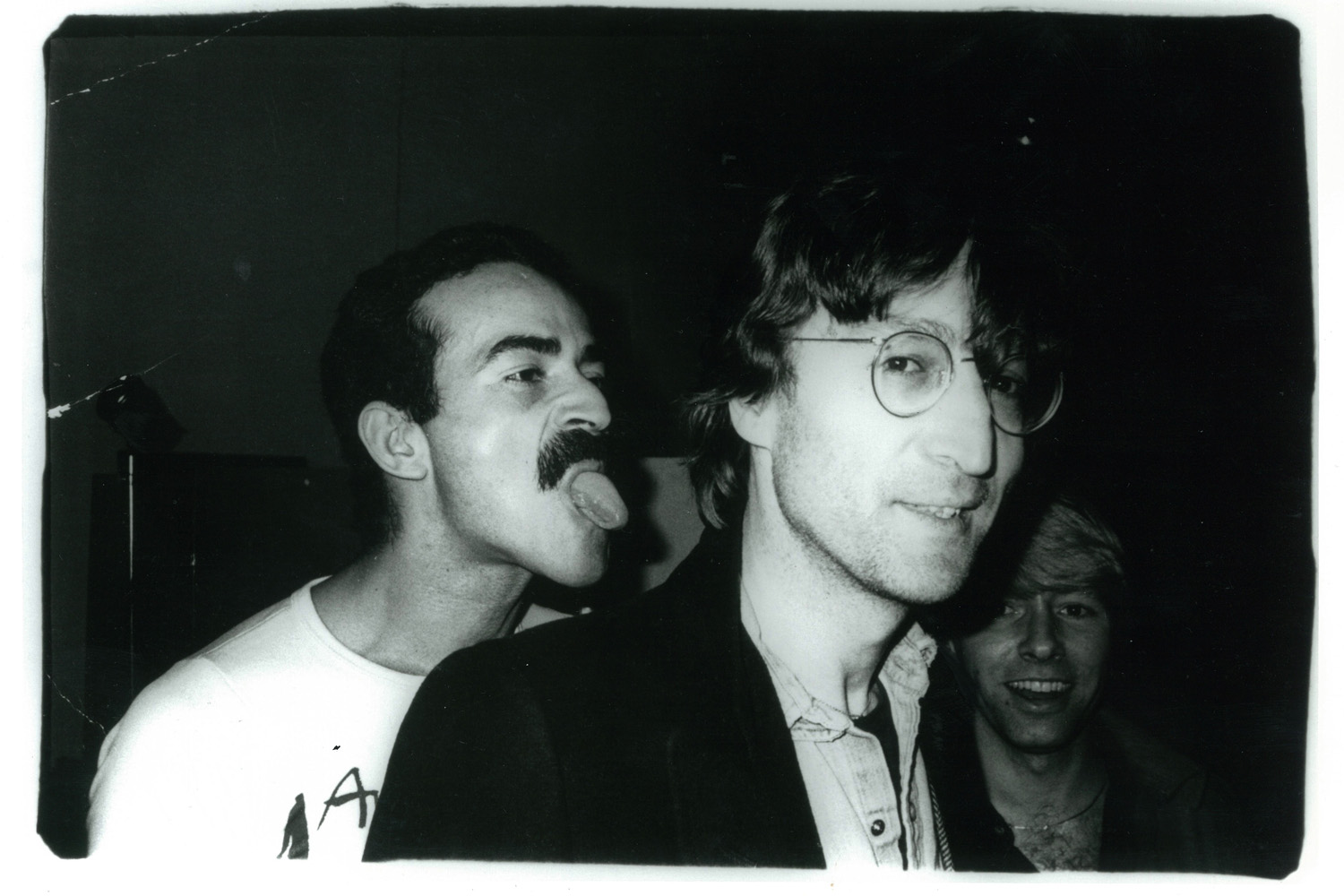

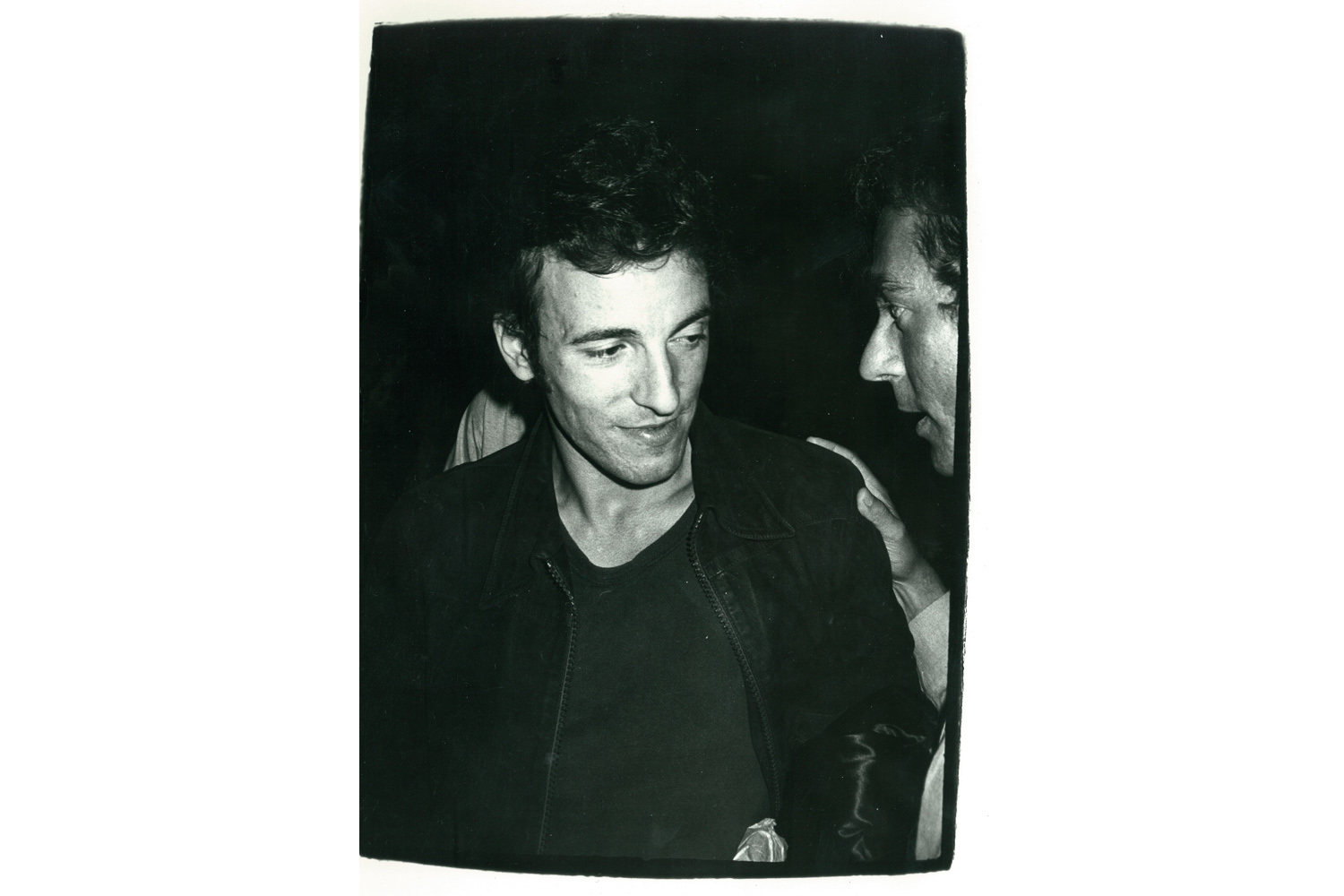

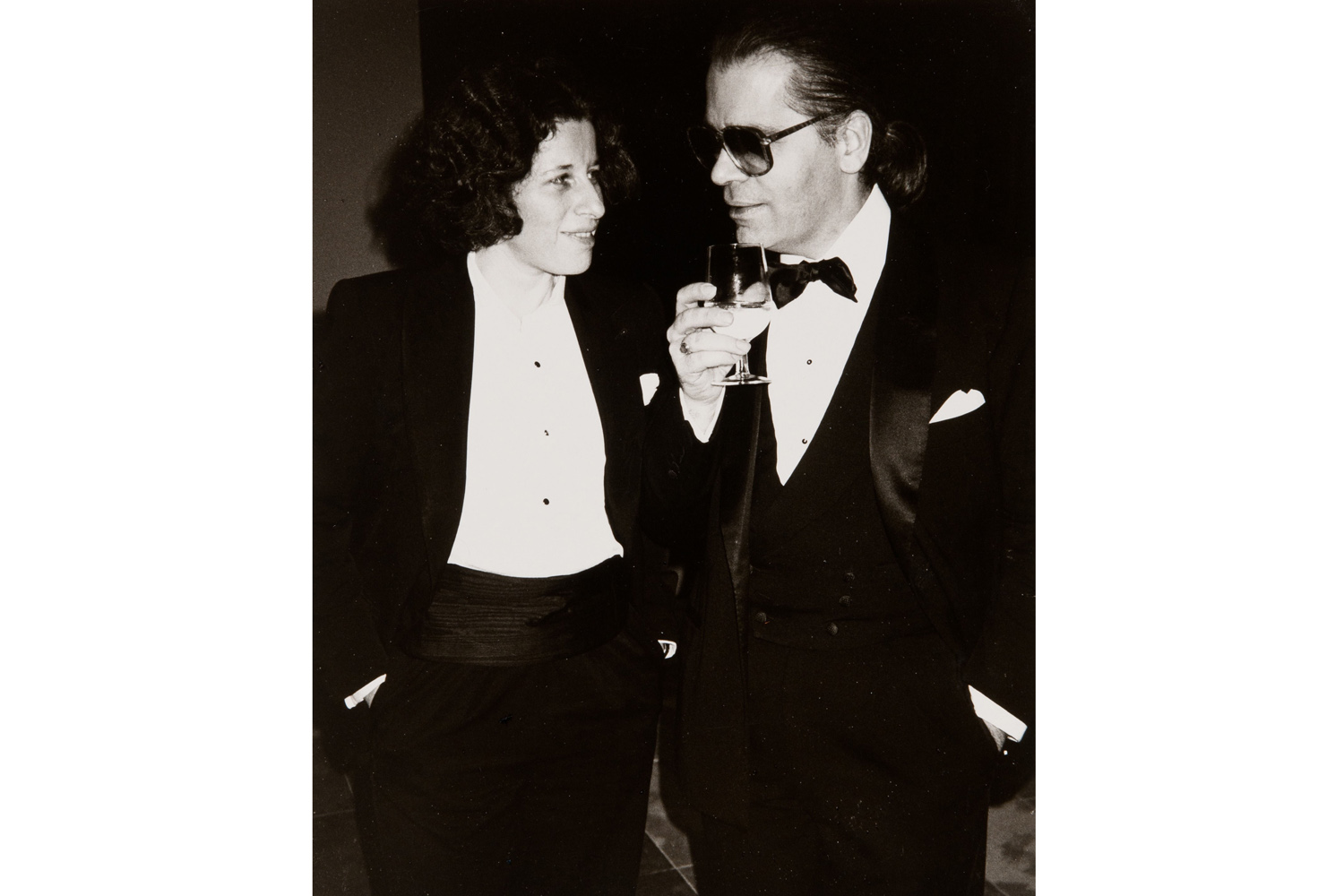

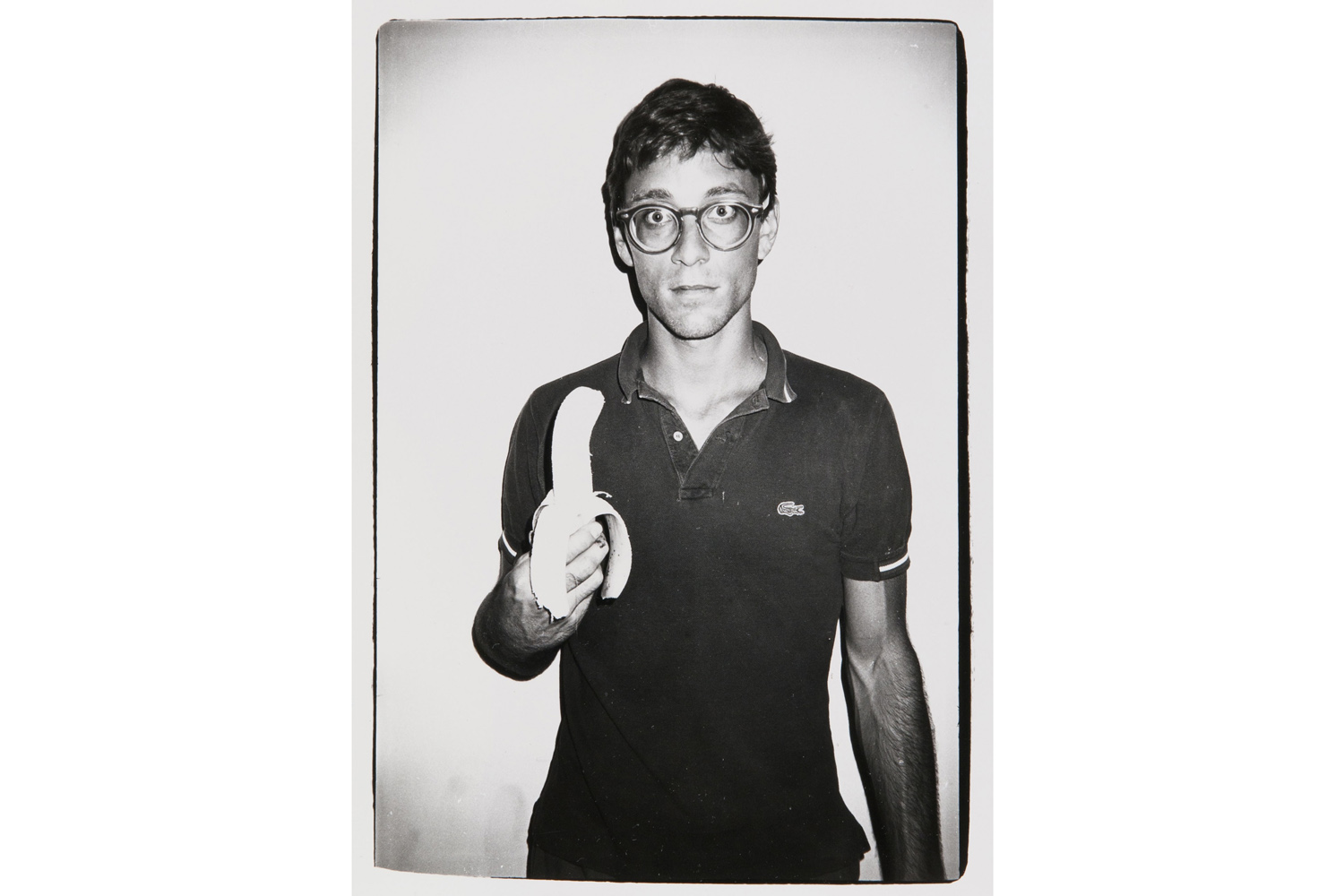

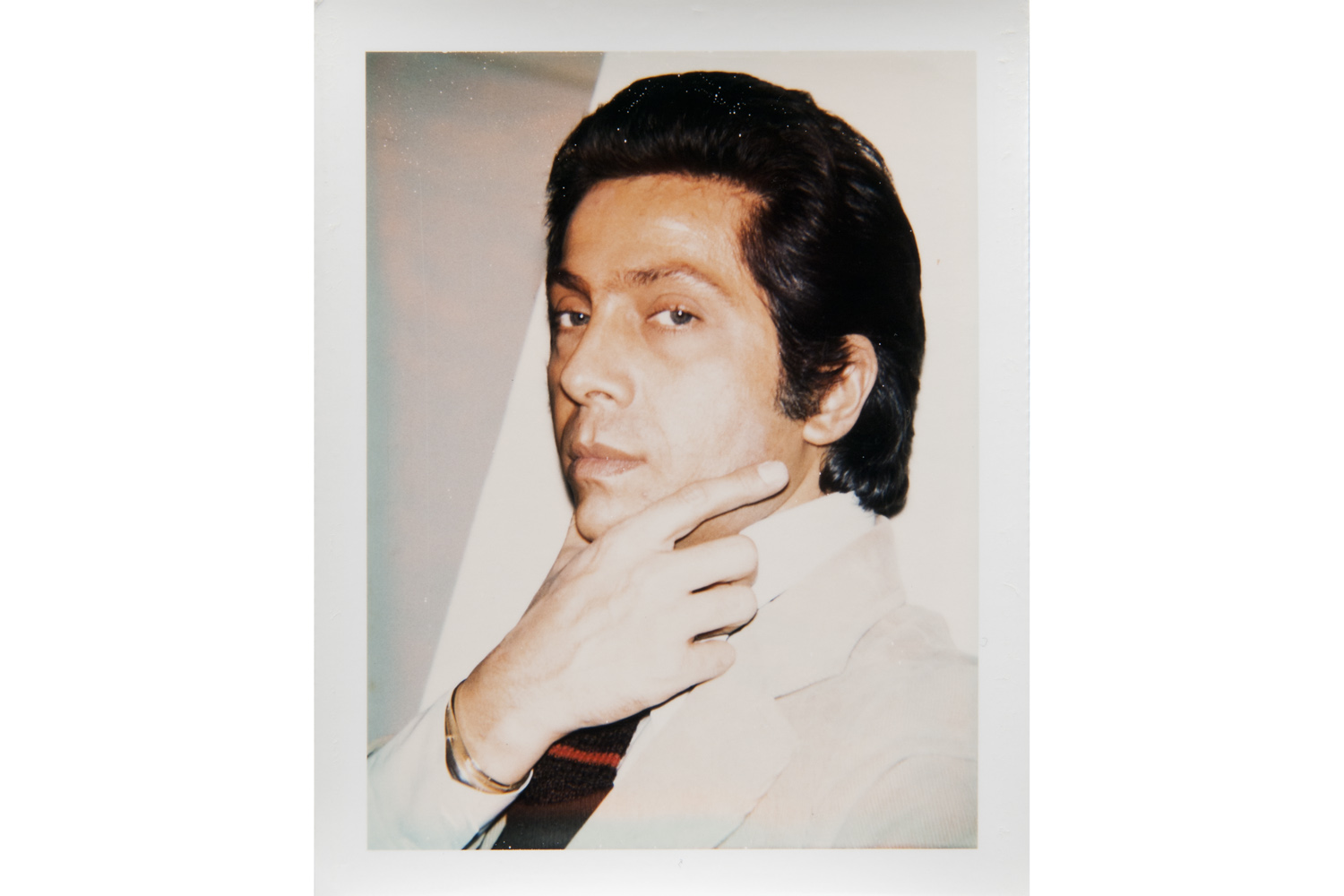

As with the production of much of his art, there was a decidedly systematic process behind the production of Andy Warhol’s photography. Beginning in the 1960s, Warhol carried a camera with him at all times, documenting every aspect of his life – from the most public to the most private, the fabulous to the mundane. When he had shot several rolls, he would hand them off to his secretary and Factory “superstar” Brigid Berlin (daughter of former Hearst Foundation president and CEO, Richard E. Berlin). Brigid would take the film to a New York photo lab to be developed and, from the contact sheets, Warhol would select the pictures he wanted as prints. From that point on, only one print of an image would be made.

These singular works represented a clear deviation from his customary, serial modus operandi of endless repetition and large editions of silkscreen prints.

But what became of those rare, individual photographic prints? Shortly before his death, Warhol mounted the one and only photography show during his lifetime in January of 1987 at Robert Miller Gallery. The rest of his photographic work – more than 50,000 still images – has remained largely unseen.

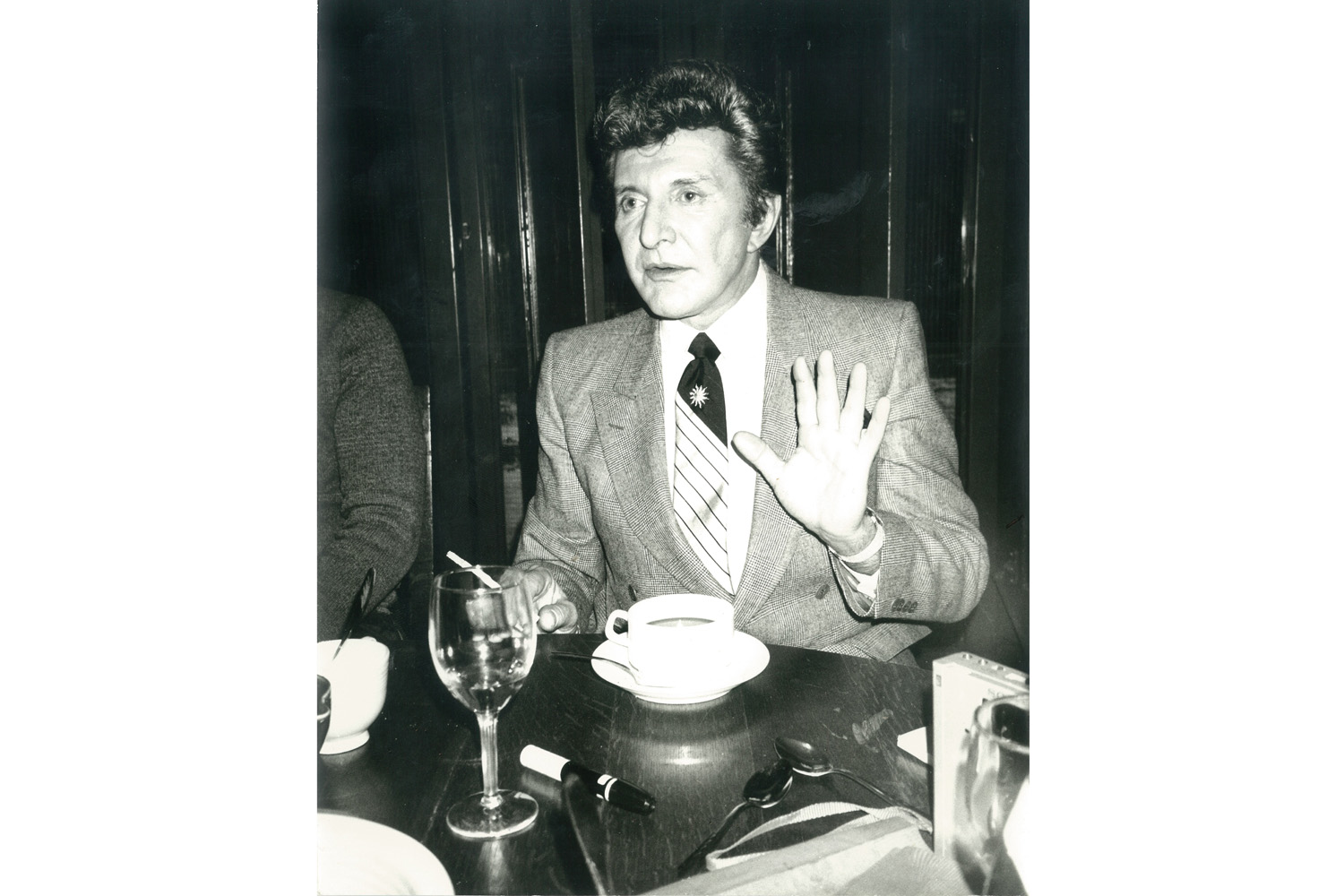

Fast-forward to 2010, when Jim Hedges, former president and chief investment officer of LJH Global Investments, announces that after 18 years, he is leaving the world of finance for the world of art. Hedges was one of the few private collectors to take an interest in Warhol’s photography and he began buying batches of it from the Warhol Foundation in the early 2000s. He currently owns one of the largest private collections of Warhol’s work. A large selection of Hedges’ collection will be shown at the New York Design Center in New York City this week in the exhibition titled, I’ll Be Your Mirror.

Hedges, a tall, gregarious, Tennessean grew up with a fascination for Warhol’s downtown Factory and poured over the pages of Interview magazine as a teenager. As an adult, he first acquired a set of Warhol’s Polaroids from the Warhol Foundation, and his obsession – and acquisitions – grew from there. The more he collected, the more he found out about Warhol and his life. People Warhol had photographed began contacting Hedges after finding out he had many of Warhol’s pictures, offering Hedges insights into the stories behind the photographs.

At one point, Bianca Jagger sent him a Facebook message saying that she’d heard he had some photographs of her. They’re now Facebook friends.

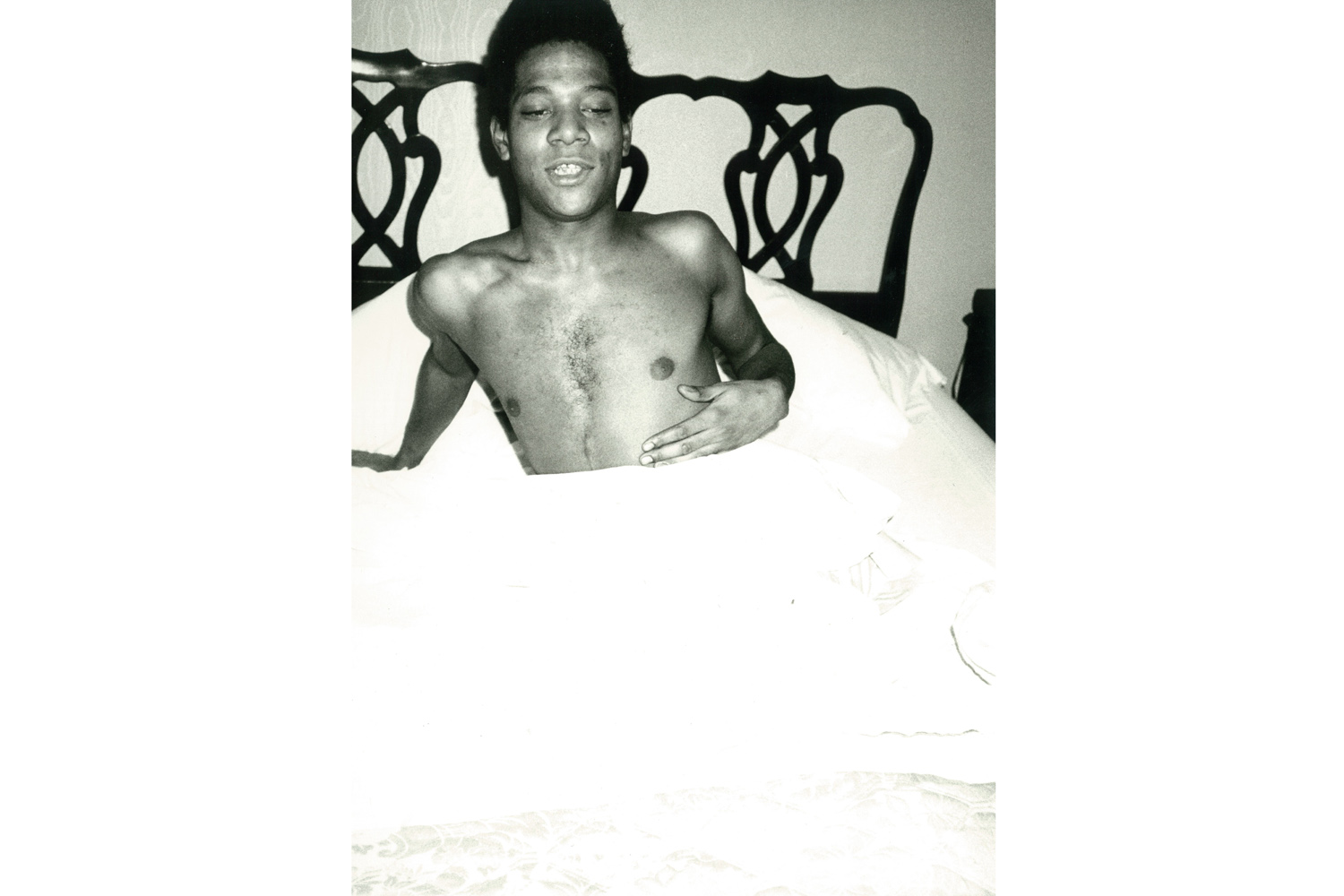

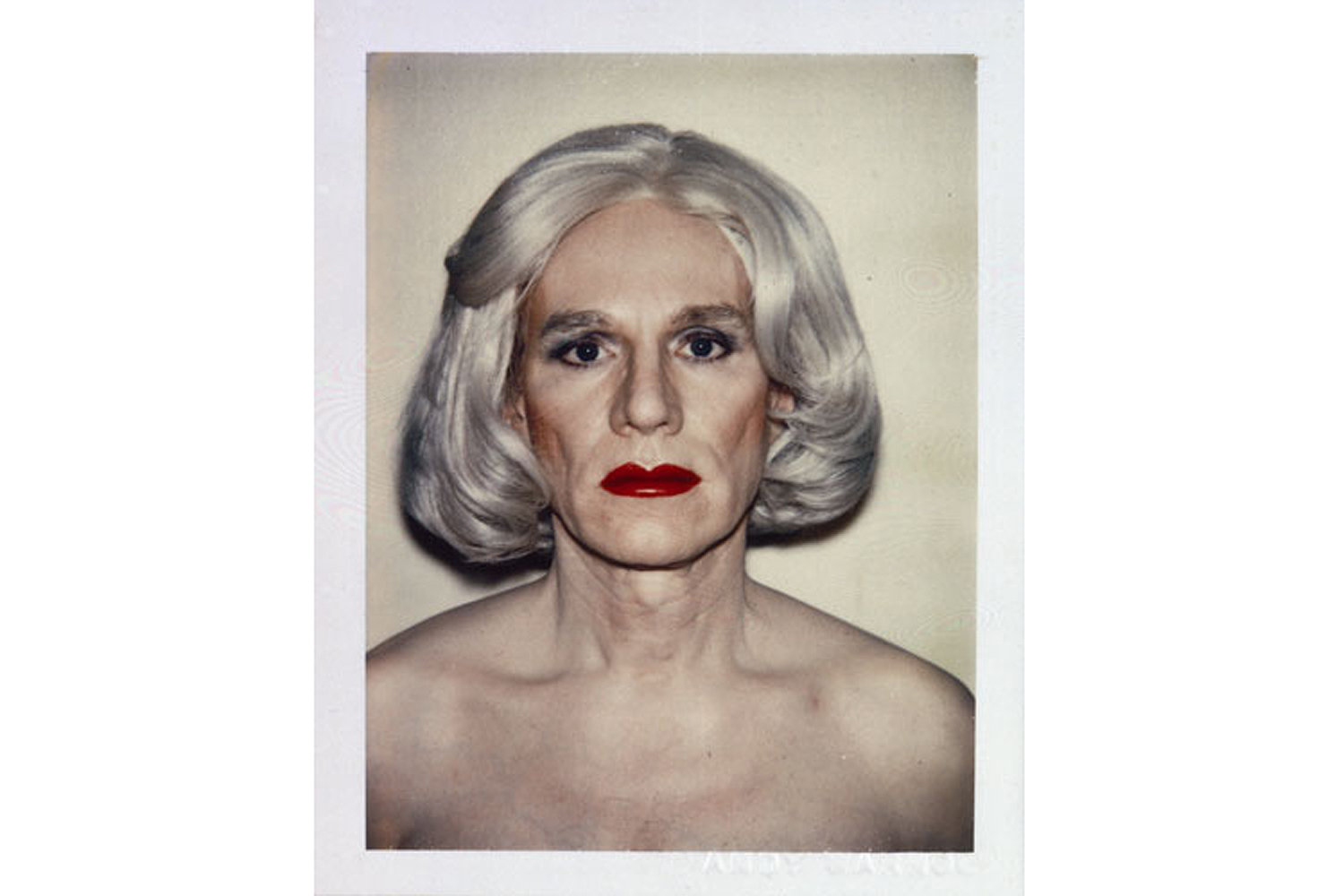

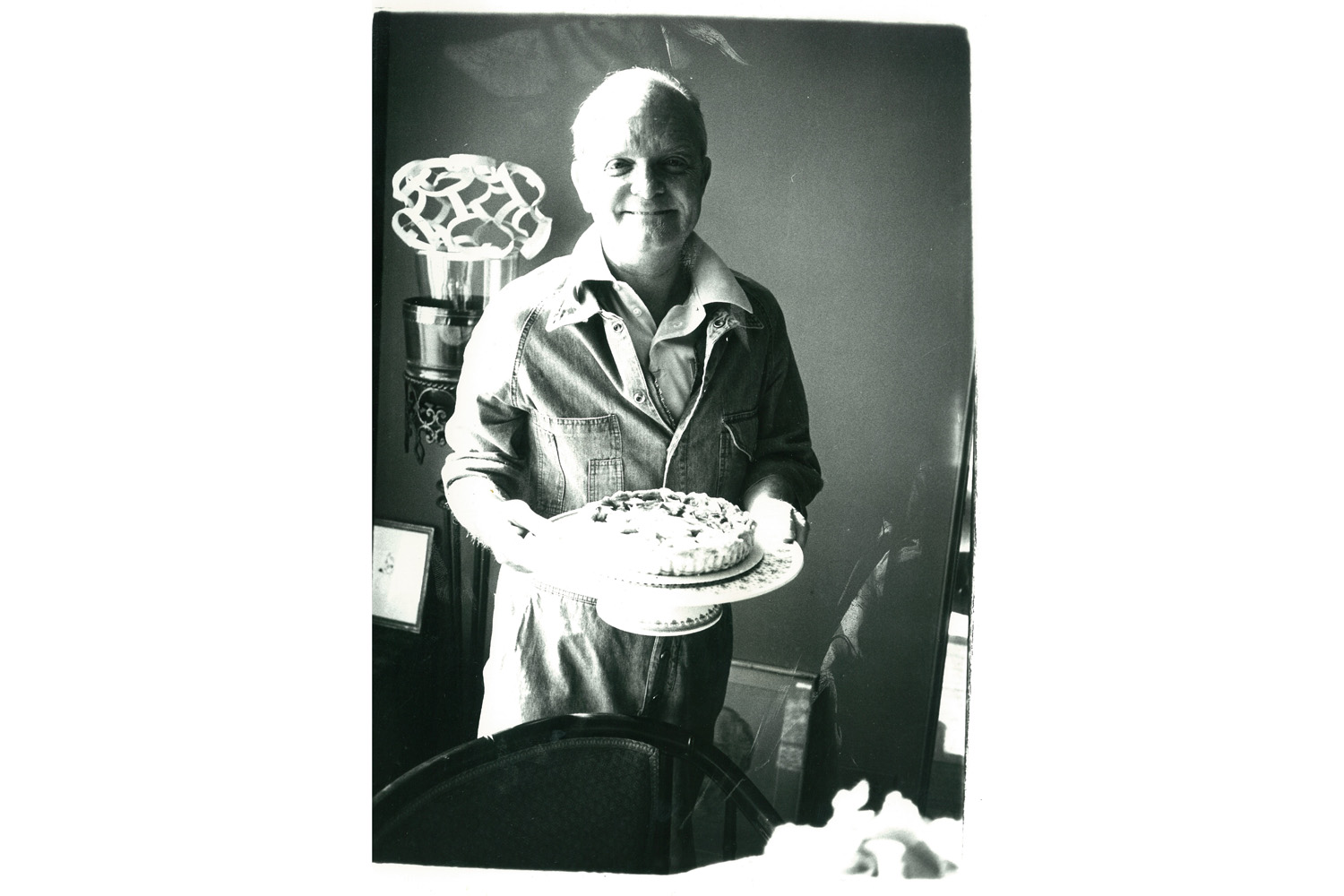

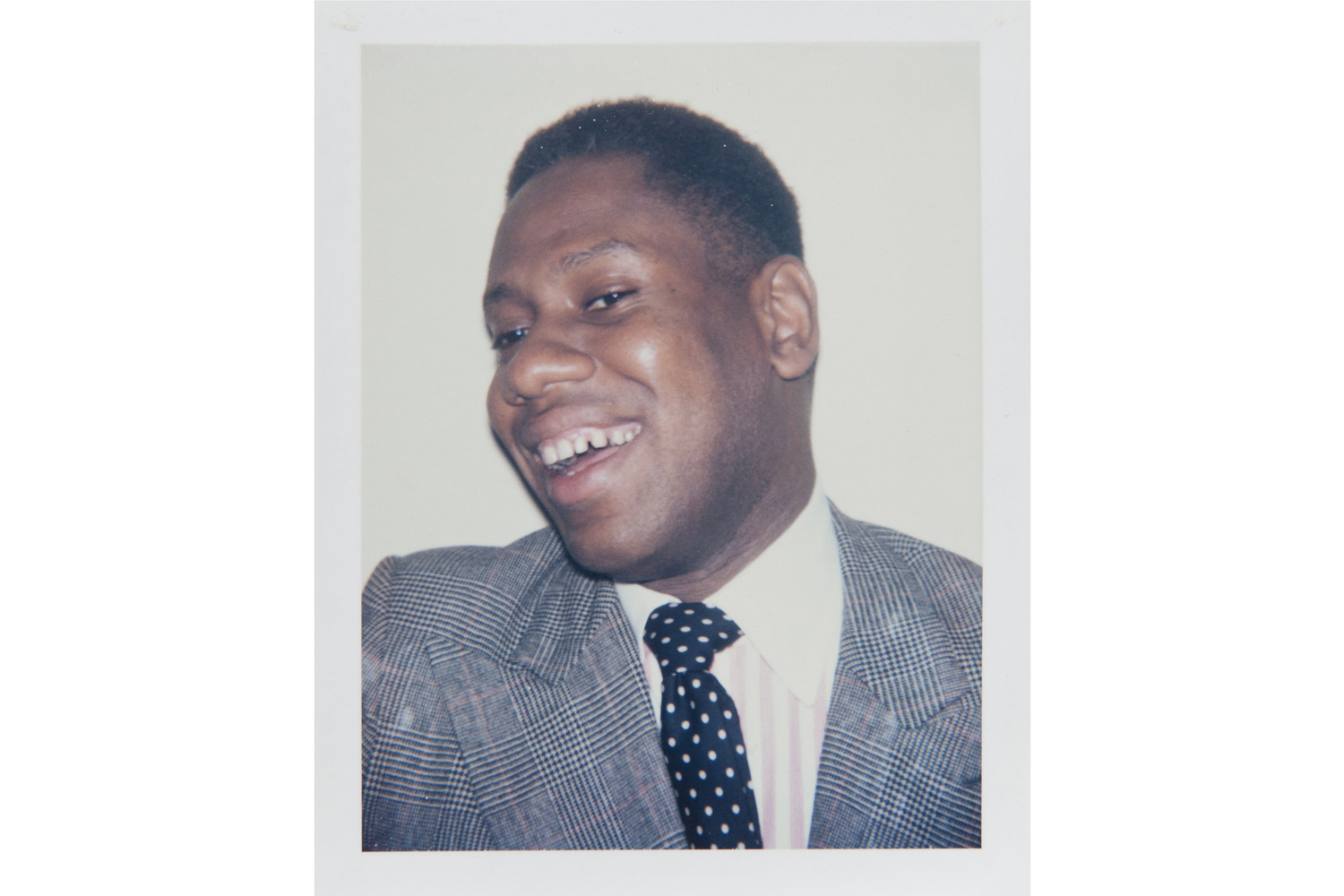

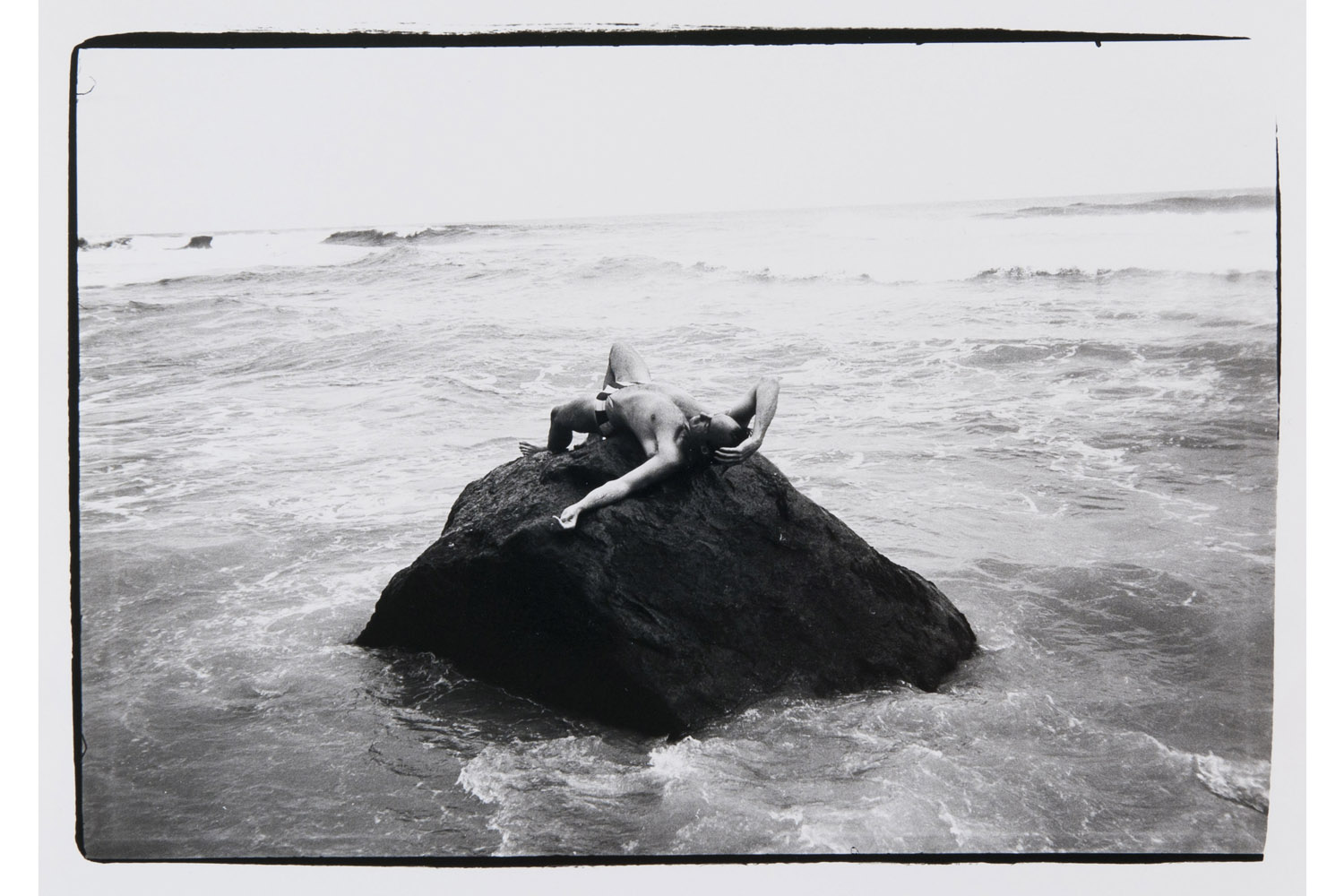

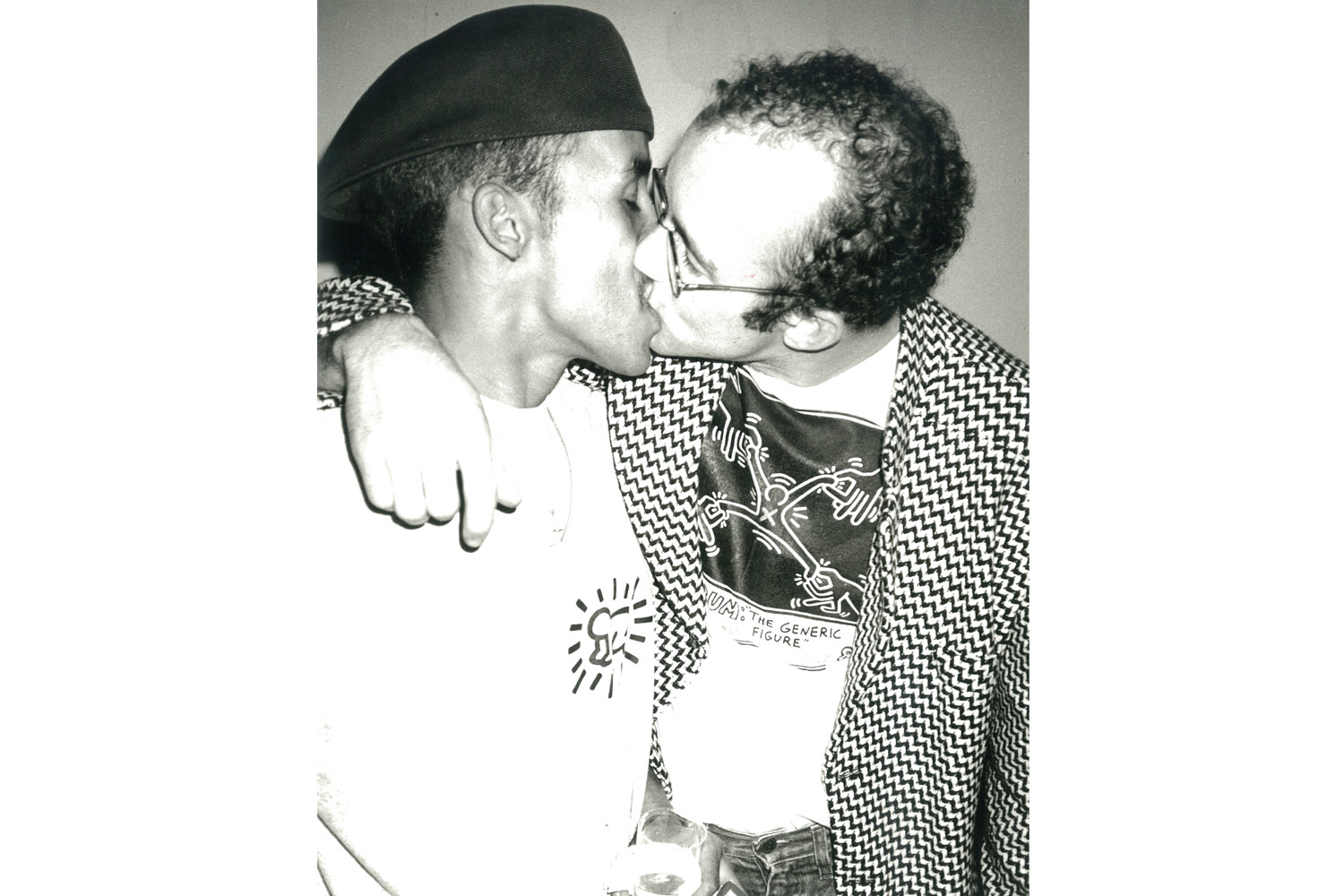

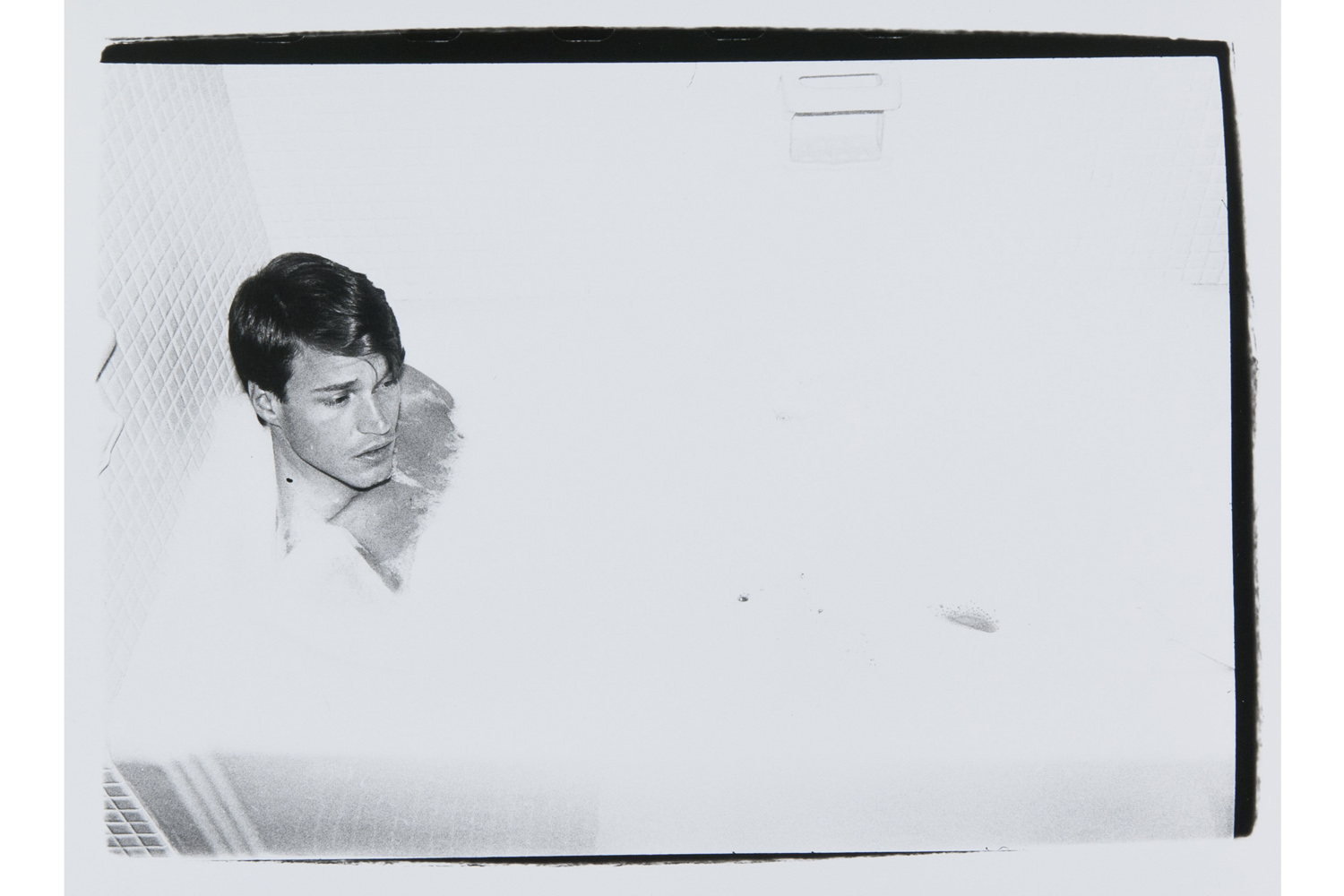

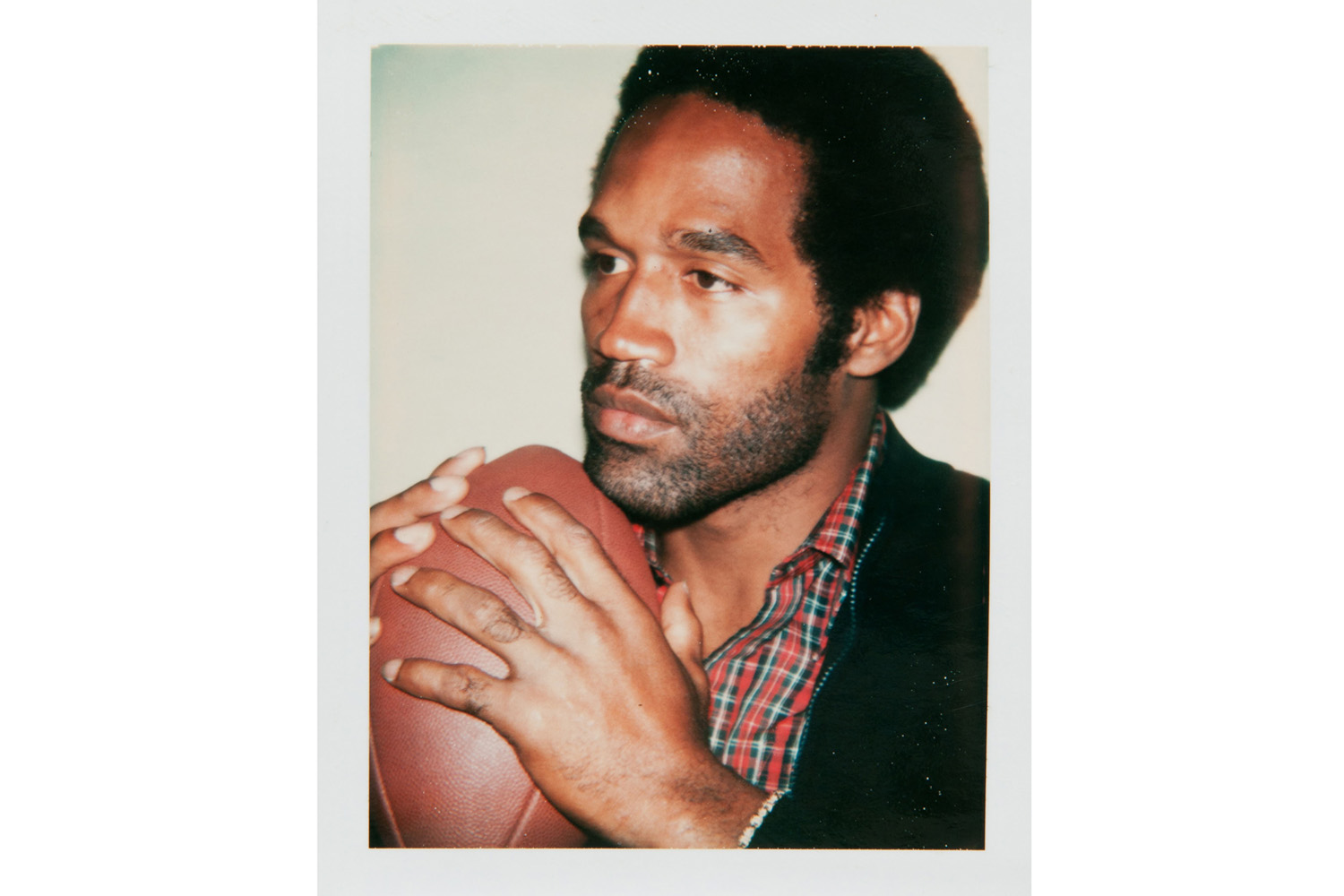

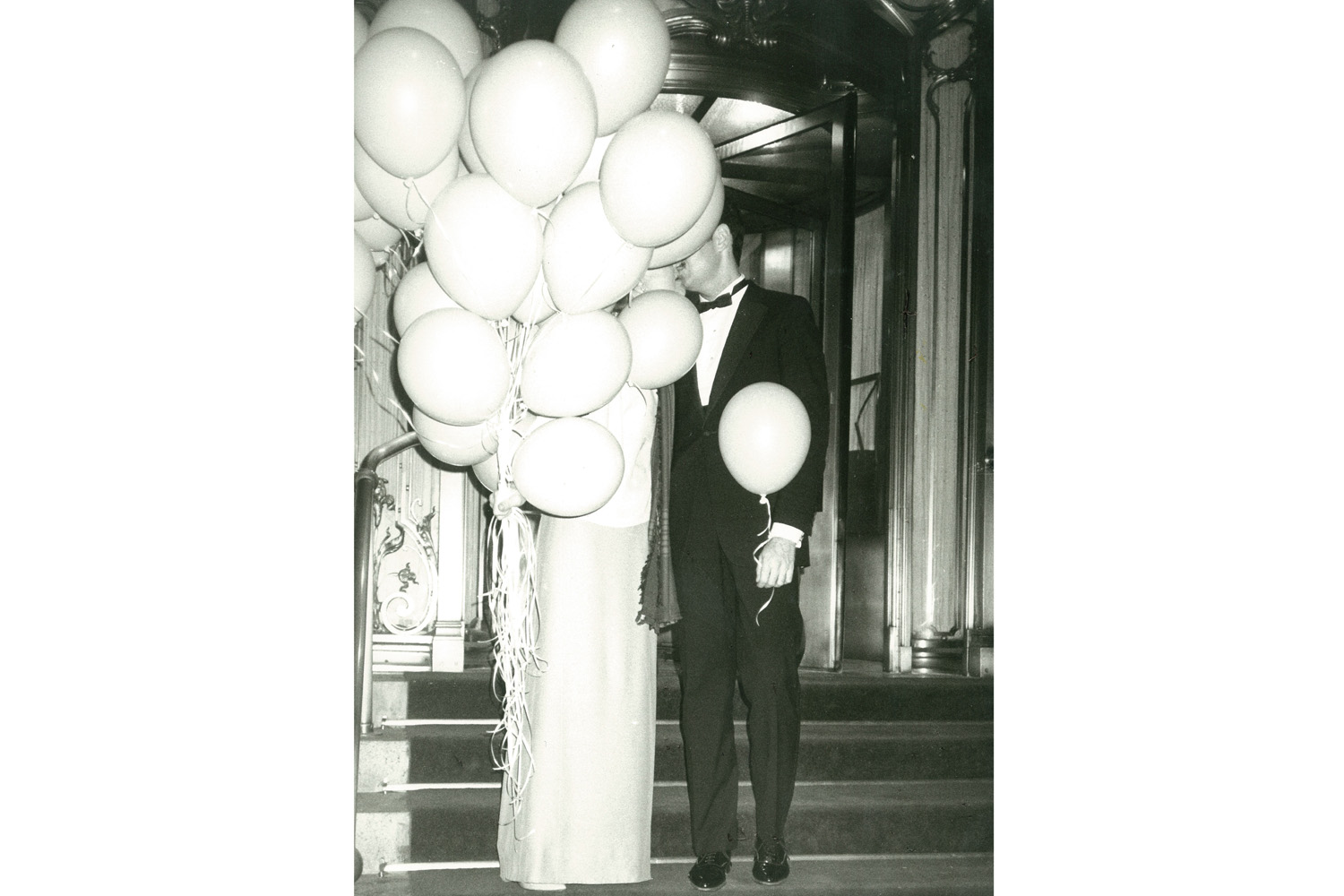

The work in the NYDC show comes not only from Hedges’ collection, but from the collection of Pat Hackett, Warhol’s diarist and frequent writing accomplice, and from Sam Bolton, Warhol’s constant companion in the latter part of his life. The show can be divided into three themes: Warhol’s social life in black-and-white 35 mm; his Polaroid portraits; and a rare, intimate set of photographs from his personal life. Hedges has thoughtfully collected the photographs into smaller, more concise groupings that reflect his deep knowledge of Warhol’s proclivities. However, among the glitz and glamor of his Polaroids and the documentation of the stars populating his societal galaxy, there are also quieter, striking photographs of his friends and lovers, offering an unexpected and welcome glimpse behind the cold, composed (and protective) Warholian veneer that the artist constructed around himself through the years. Though photography was an intrinsic part of Warhol’s work, it also seems that it was an equally integral part of his life. And though he has been in the spotlight for decades, so much of his shadow has yet to come to light.

Andy Warhol’s unseen photographs are on view in I’ll Be Your Mirror at 1stdibs’ 10th floor gallery in the New York Design Center, Sept. 10 – Oct. 7, 2013.

Mia Tramz is an Associate Photo Editor at TIME.com. Follow her on Twitter @miatramz.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Inside Elon Musk’s War on Washington

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Cecily Strong on Goober the Clown

- Column: The Rise of America’s Broligarchy

Write to Mia Tramz at mia.tramz@time.com