For decades, the act of setting fire to photographic negatives — frequently an entire archive’s worth of negatives — has been one of the signature ways that artists have signaled an incandescent end to one part of their careers. The aesthetic and intellectual sparks behind this irretrievable gesture, meanwhile, are as varied as the sensibilities and the work produced by artists through the years.

Japanese photographer Takuma Nakahira, for instance, whose first U.S. solo exhibition was recently on view at Yossi Milo Gallery in New York, burned his entire early archive in 1973. A pioneer, with Daido Moriyama, of the “are, bure, boke,” or “rough, blurred, out of focus” style, Nakahira had grown increasingly concerned that his work might descend into cliché. Weary that he was going too far in “assert[ing] control over the world in the ‘poetic’ treatment of reality” — as Franz Prichard, a Postdoctoral Fellow of Japanese Studies at Harvard, phrased it in an email to TIME — Nakahira piled up his negatives and destroyed the source for all his imagery.

Drawn to what Prichard deems the “transformative charge of fire,” Nakahira was determined to break from convention, destroying ties to the authority of his own past in an effort to reinvent himself completely as an artist.

Commonly viewed as an optimal medium for preserving images, film is in fact one of the most fragile. The first commercially available film was largely based on nitrate — in effect, a low-order explosive. Extremely combustible, nitrate film exposed to enough heat will literally burst into flames. By the early 1950s, however, nitrate was replaced by acetate-based, or “safety film,” which melts and bubbles more often than it burns. Safety film will, under the right conditions, catch fire and disintegrate; but it’s not quite the same as the incendiary effects of the classic nitrate fireworks.

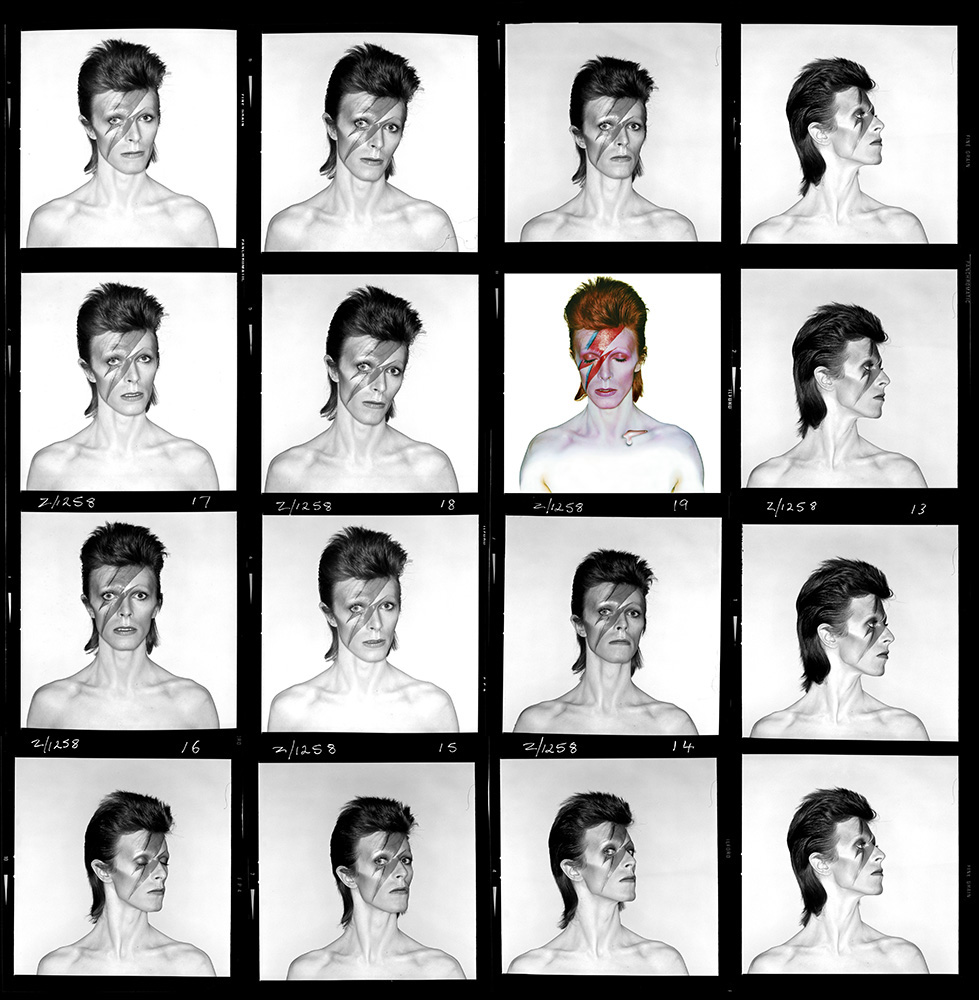

Brian Duffy, an English photographer best known for his portraits of ’60s and ’70s cultural figures (Bowie, William Burroughs, Michael Caine, etc.), decided in 1979 that he would never make another picture — and he never did. Increasingly disenchanted with the commercial turn of his career, “I went into a burning mode,” he once told the BBC.

“I felt everything I had to do and say in photography had been done,” he said. Pointing to the accomplishments of portrait artists like Irving Penn and Richard Avedon, he said “they f—ed photography for [the rest of] us. … They got there.”

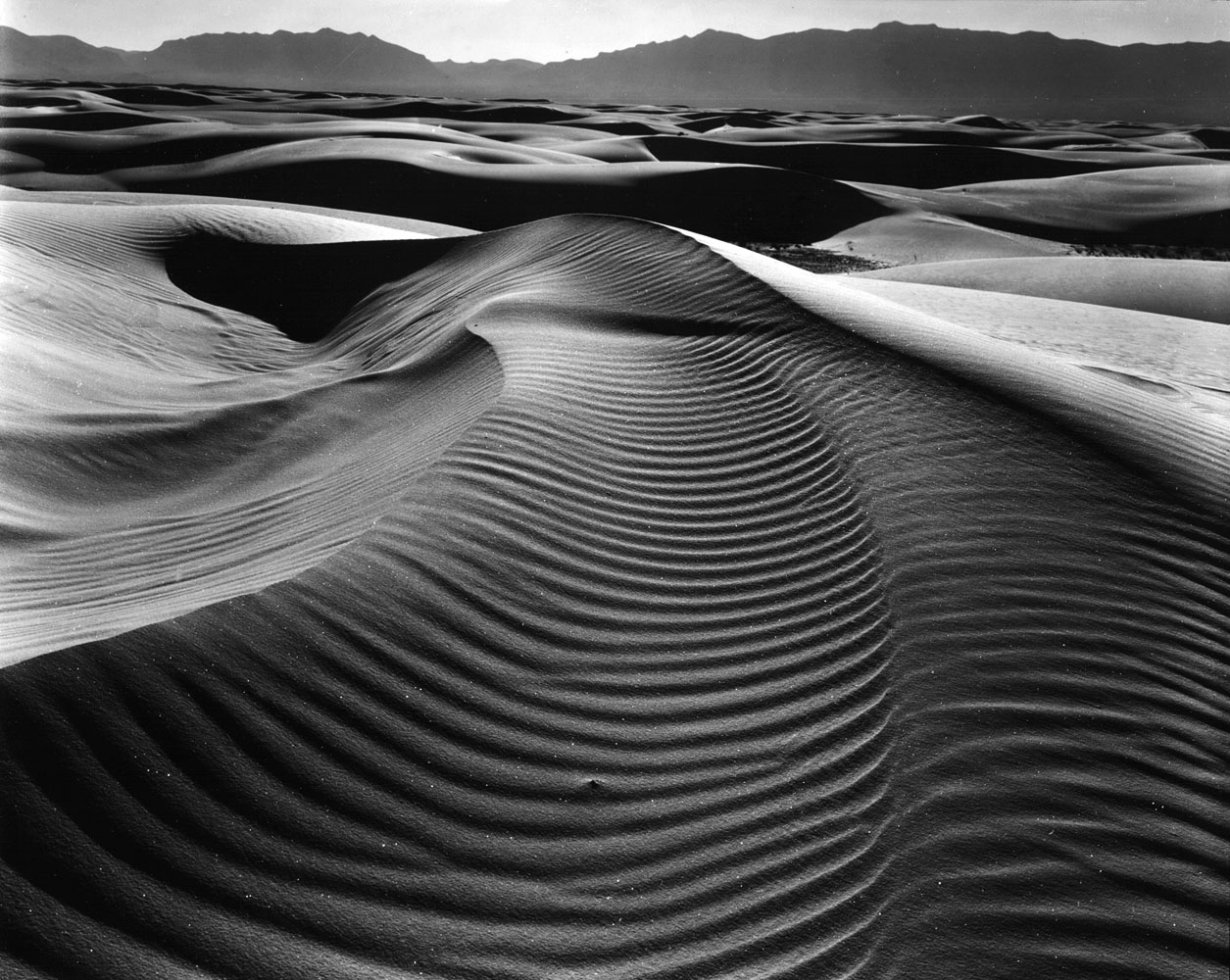

Not all photographers, however, have burned their negatives due to their tortured connection to the past. Some, like Brett Weston, are instead passionate about exerting absolute control over their legacy — in other words, over what gets left behind.

Weston, on his 80th birthday and two years before his death in 1993, surrounded by friends and family, tossed every one of his negatives into a brightly burning fireplace in his home in California. He had been promising to destroy all his film for more than two decades in a bid to pass on ultimate control over the editioning of his work to his estate.

“Nobody can print [my work] the way I do,” he told the Associated Press. “The prints are posterity, not the negatives. … I don’t want students and teachers to print my work.”

Similarly, though with a bit more pageantry, Edward Steichen “wanted to leave behind only the negatives that he found of aesthetic value or of historical importance,” writes his wife Joanna Steichen in her introduction to Steichen in Color. In the 1960s, Steichen began what she describes as a “frantic process” of destruction.

“He tried burning them and burying them in the swamp. Finally, by the time I arrived … they were being tied up in bundles, taken out to the middle of the pond and dumped; the water washed away the emulsion.”

Steichen and Weston took to burning their archives in the twilight of their lives; ocasionally, artists begin this process in their prime.

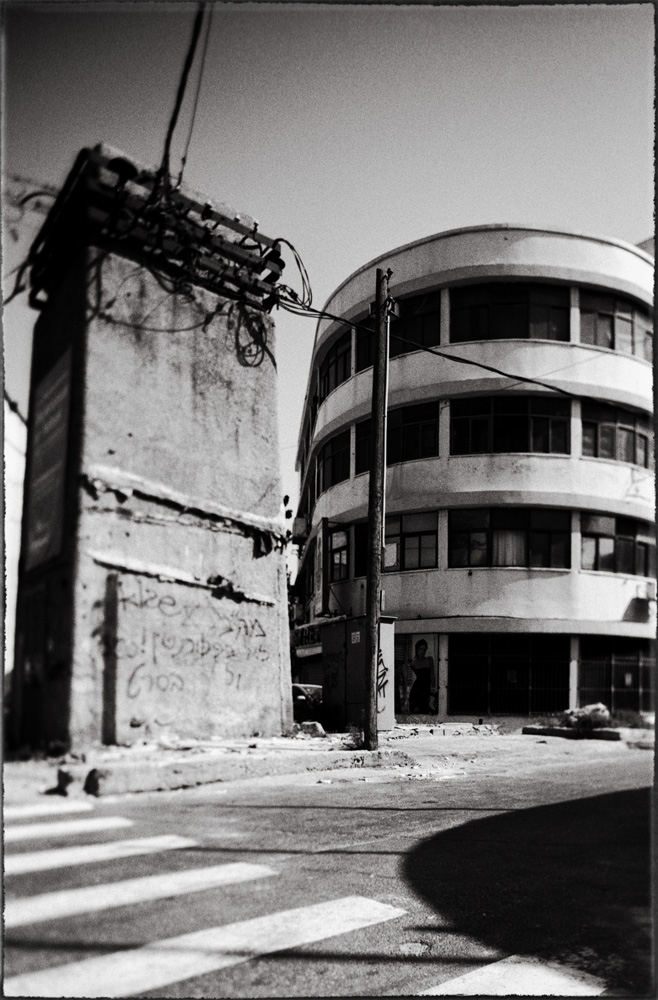

In 2009, Jean-Baptiste Avril was commissioned by a gallery in Israel to work on a project on the architecture of Tel Aviv. He shot about 17 rolls of film; the gallery hosted a successful exhibition of 12 large-format gelatin prints and produced an accompanying catalog. Avril was subsequently approached by cultural institutions and editorial outlets throughout Israel and Europe, all requesting to exhibit or republish the work — but offering no compensation, other than the publicity.

“So my work has to be for free!” he wrote in an online forum. “All right! As it has no value I don’t see the need for it to physically exist much longer.”

He tossed roll after roll of film into his fireplace, documenting and publicizing the event. But, as Paul Melcher, a senior editor at Le Journal de la Photographie, points out, Avril “conceded he scanned them all in advance, making the gesture rather hollow.”

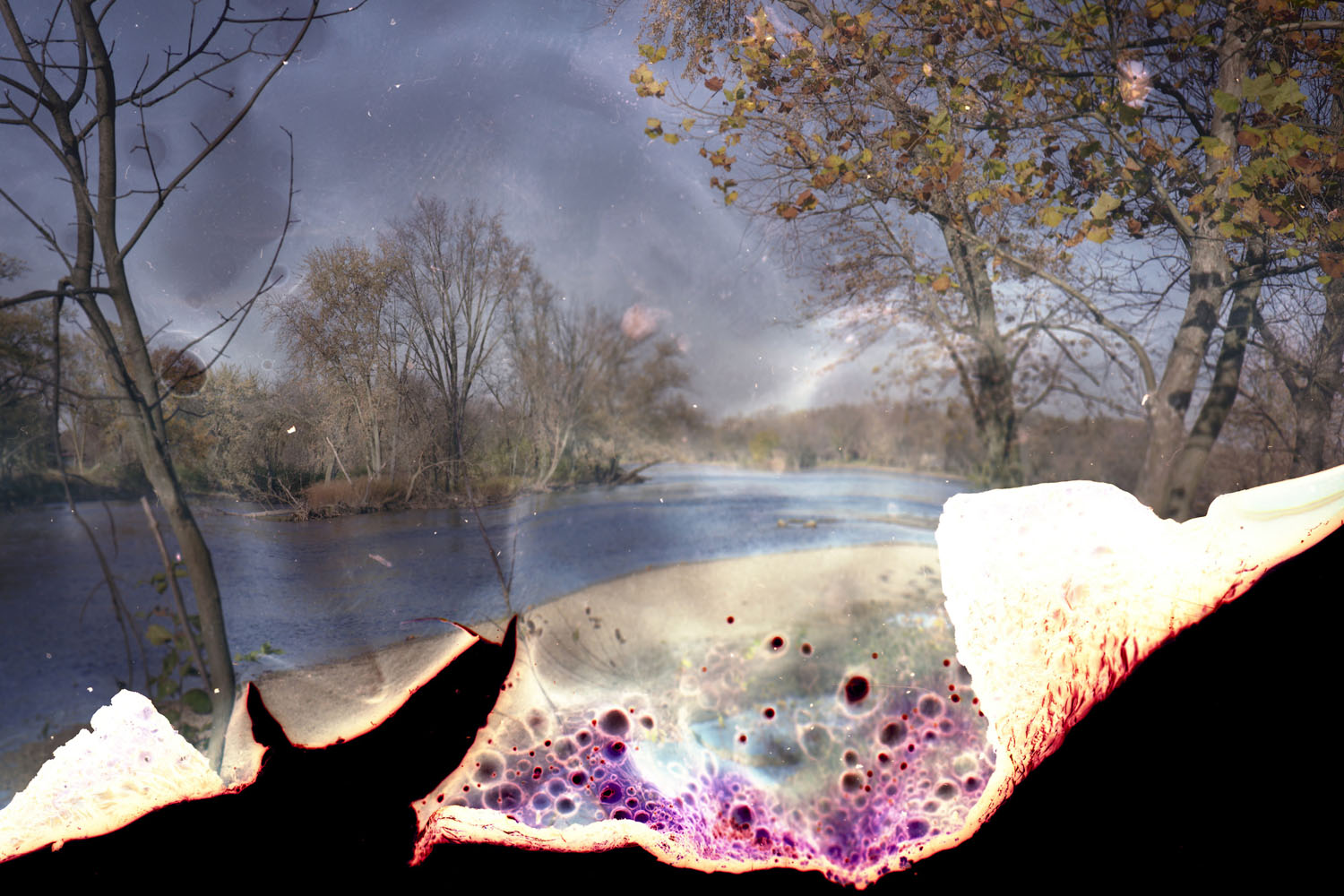

In the digital age, as the act of burning negatives has perhaps lost something of its significance, artists — like John Baldessari years ago with his “Cremation Project” — have made performance art itself of the act. Contemporary photographers like Eric Dallimore and Brent Losing, meanwhile, have adopted it as a visual aesthetic, incorporating elements of chance into their work, producing one-of-a-kind, continuously deteriorating sculptural objects. These photographers burn and melt negatives incompletely to make distorted images while capturing the fleeting visuals of the act itself.

Peter Hoffman, a Chicago-based photographer, also brought this method to his Fox River Derivatives series on oil spills. He shot pictures along the Fox River near Chicago, soaked them in petroleum fuel and set them alight. Partially burned, the resulting images interweave form, process and content, all at once.

All of which raises the question: How will photographers working solely in the digital realm — in which, as we all know, nothing is ever truly lost — assert control over their own legacies? How after all, do you burn ones and zeroes?

Eugene Reznik is a Brooklyn-based photographer and writer. Follow him on Twitter @eugene_reznik.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com