The honeybee is the most geometrically minded of insects. The honeycomb that bees build with wax is always laid out in quasi-horizontal, non-angled hexagonal cells, to be filled with bee larvae and stores of honey and pollen. It’s a perfect shape, repeated over and over again each time a honeybee colony builds out its hive. This is deep geometry.

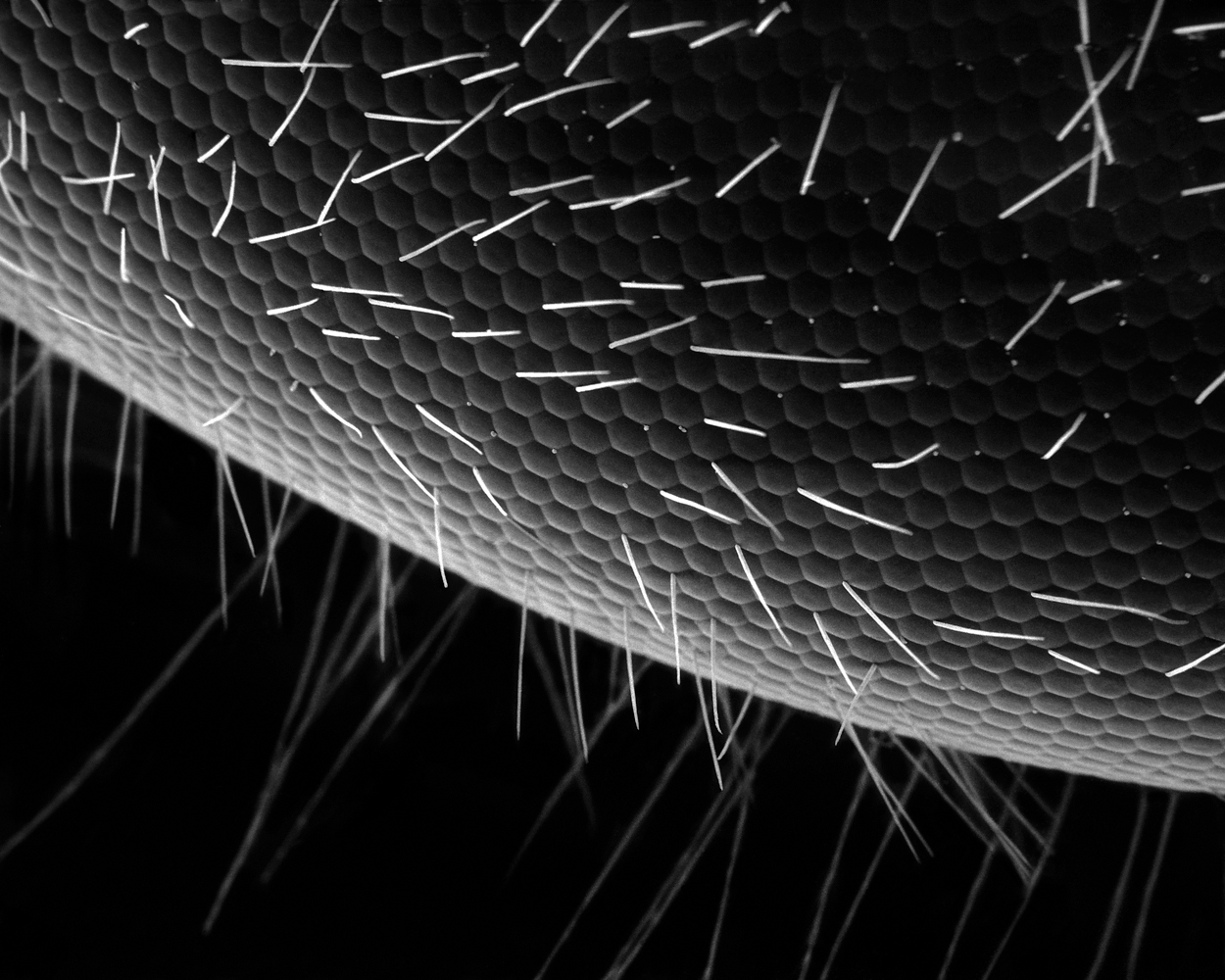

The first time photographer Rose-Lynn Fisher looked at a bee’s eye magnified through a scanning electron microscope, she saw that same repeated hexagonal pattern. She was struck by the symmetry. “There was an echoing of the hexagon in the structure of the bee’s eye, just like the pattern of the honeycomb in form and structure,” she says. “Is it a coincidence? A clue?”

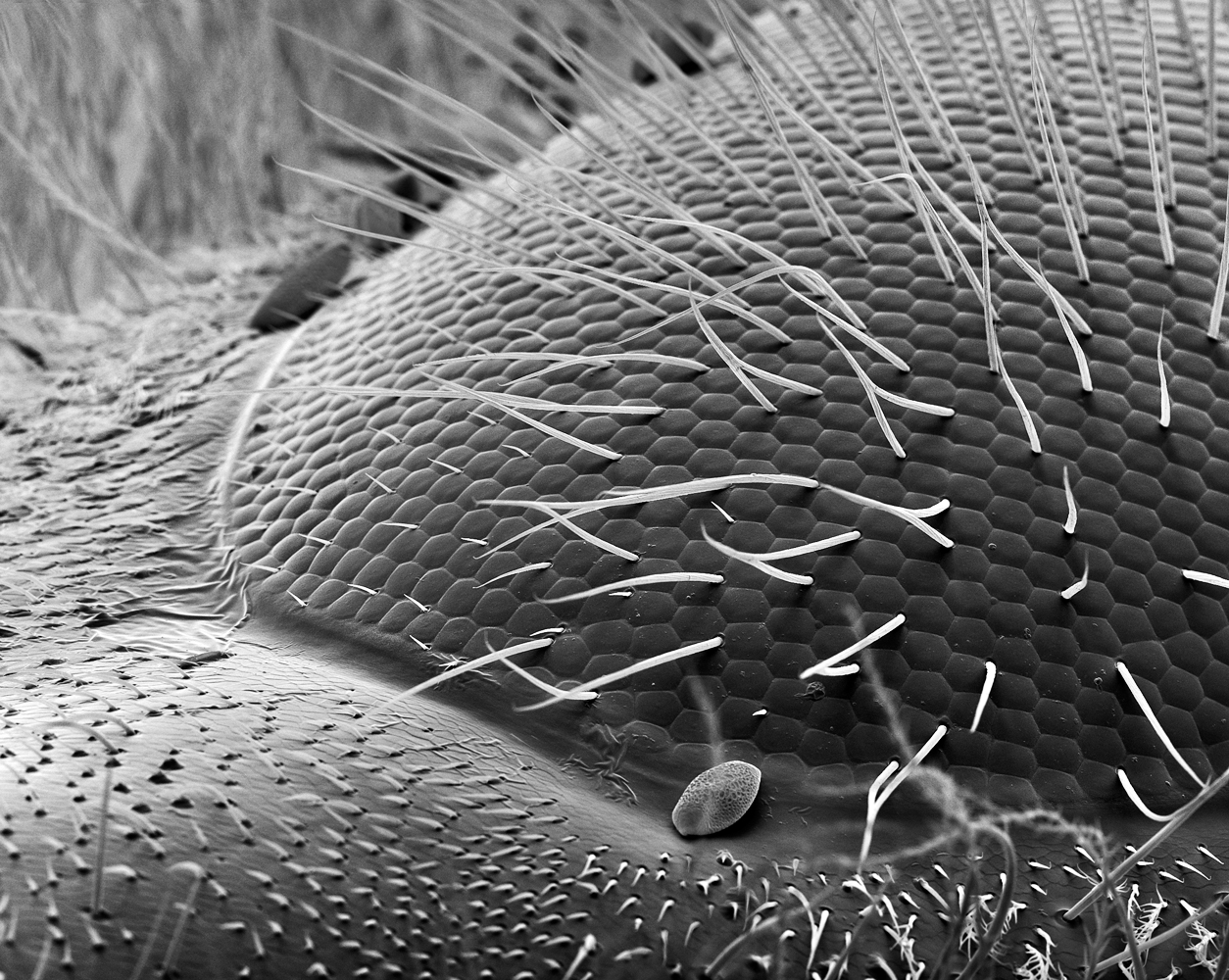

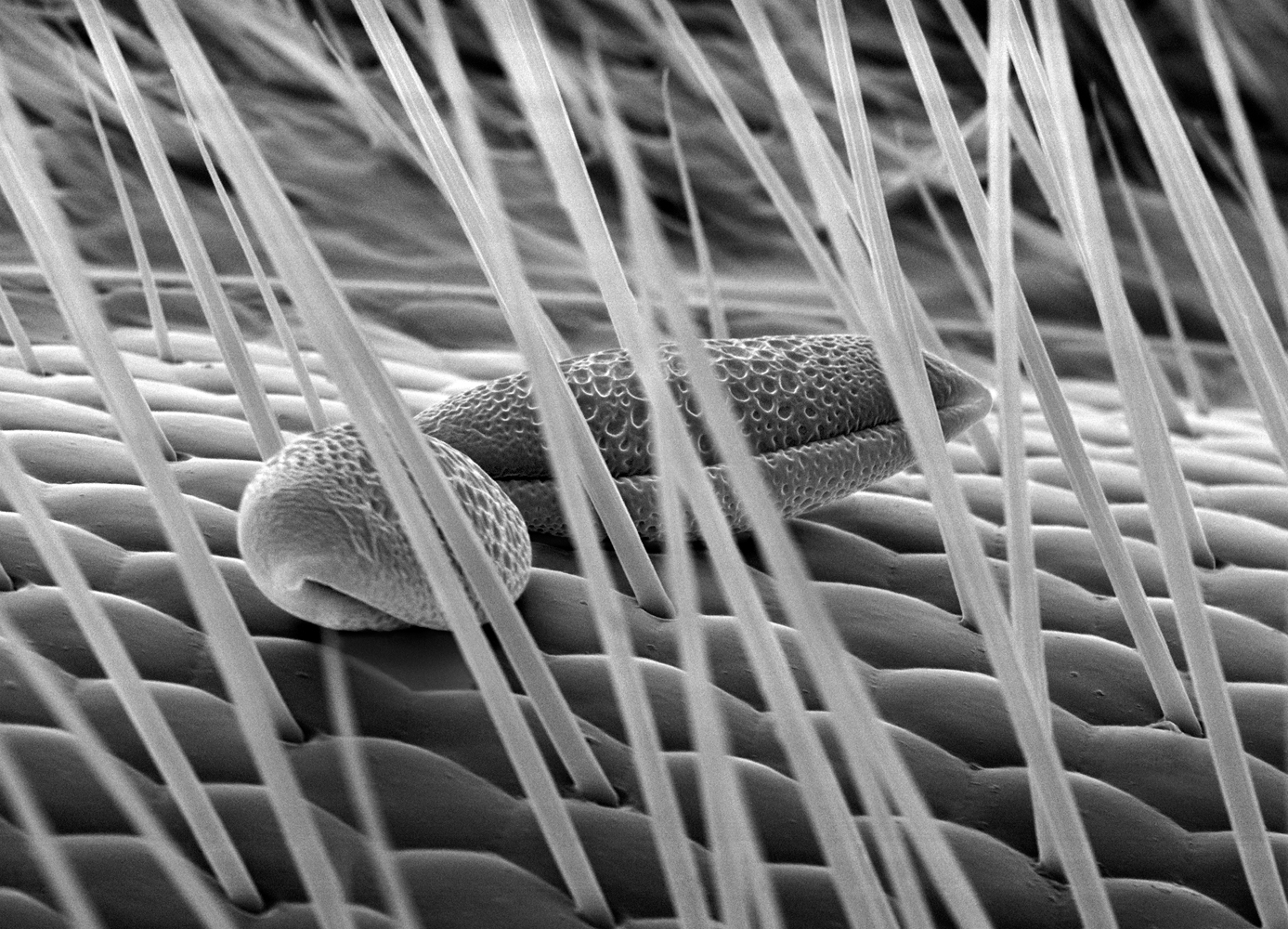

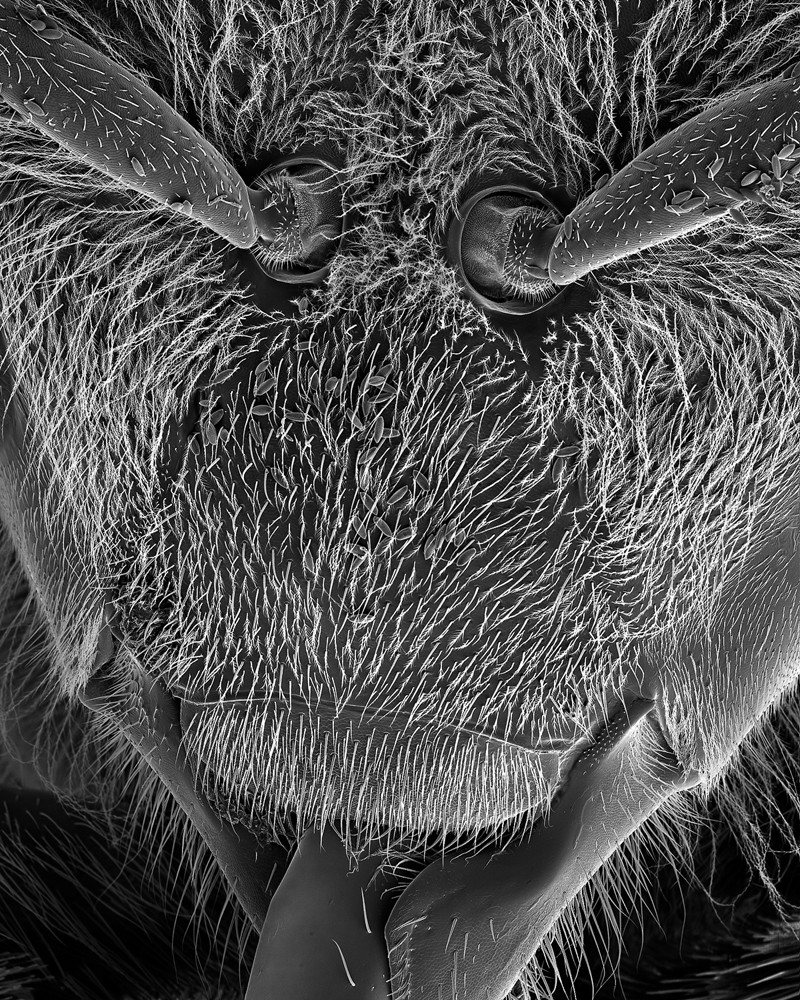

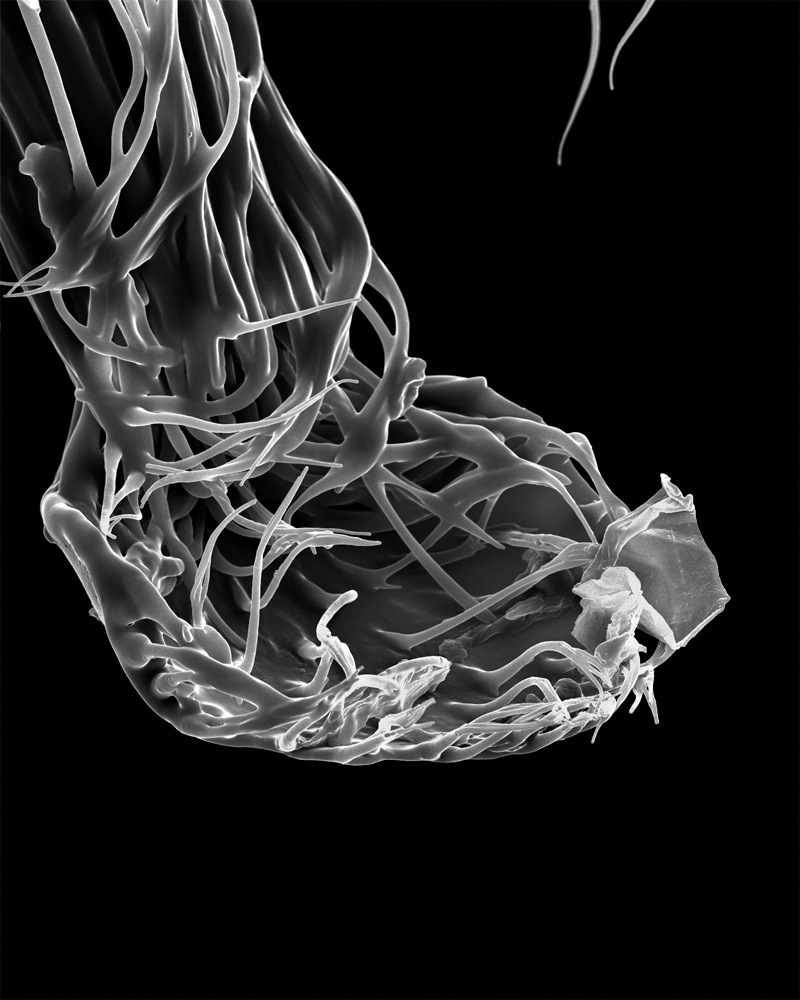

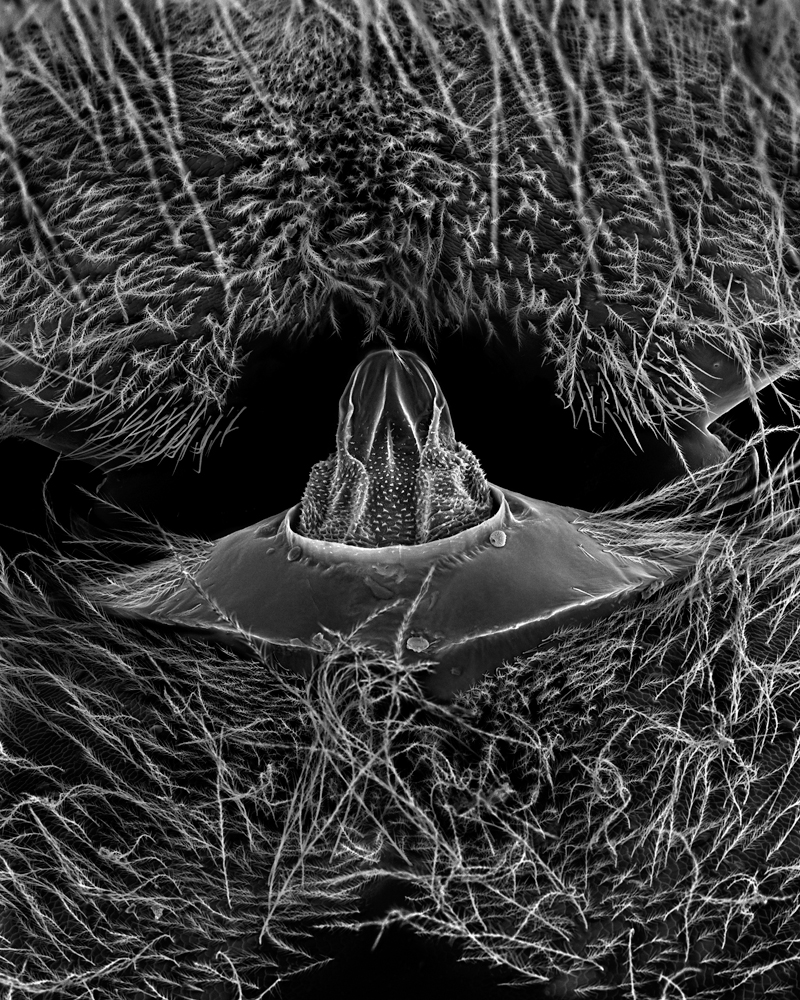

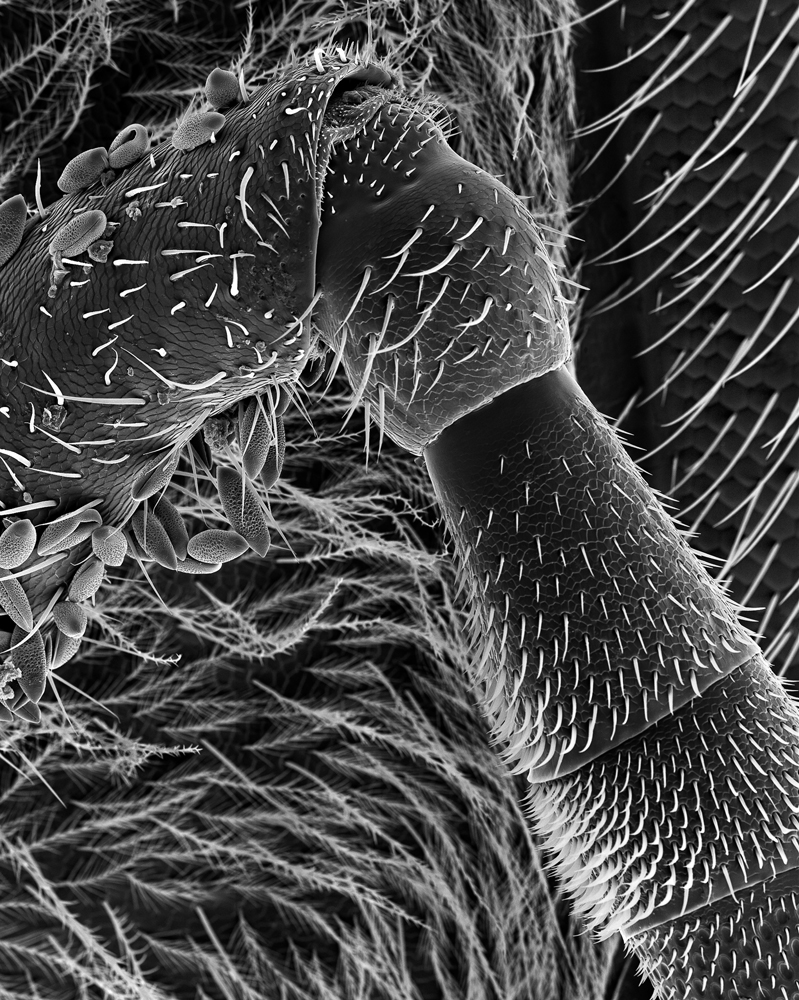

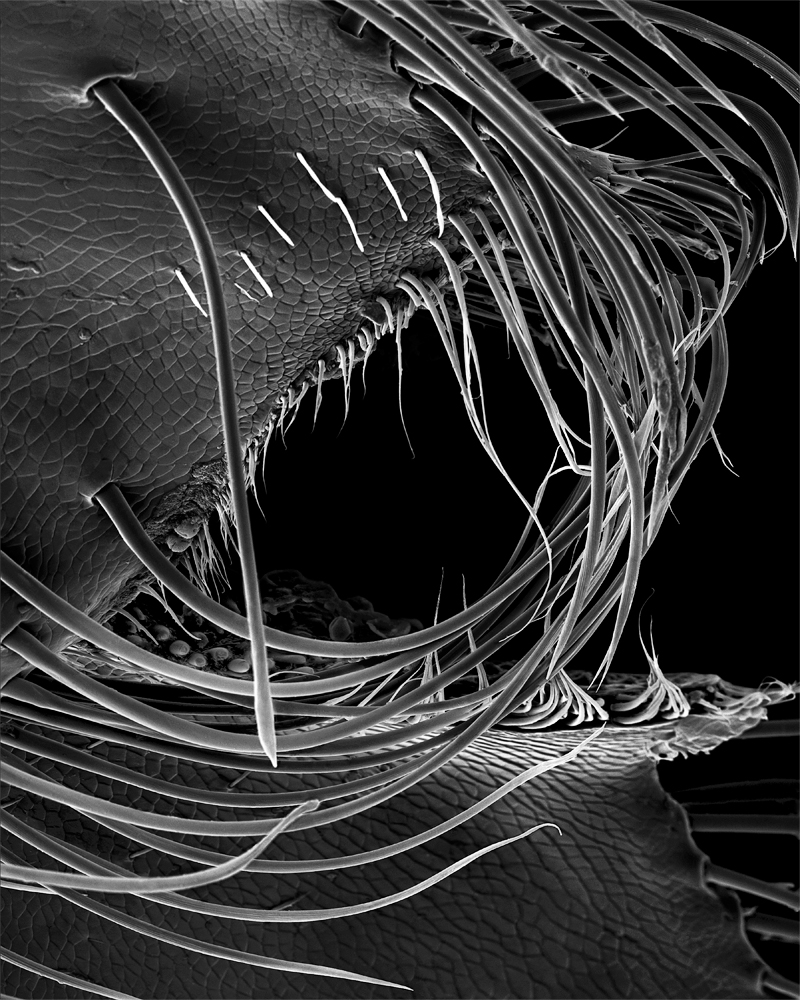

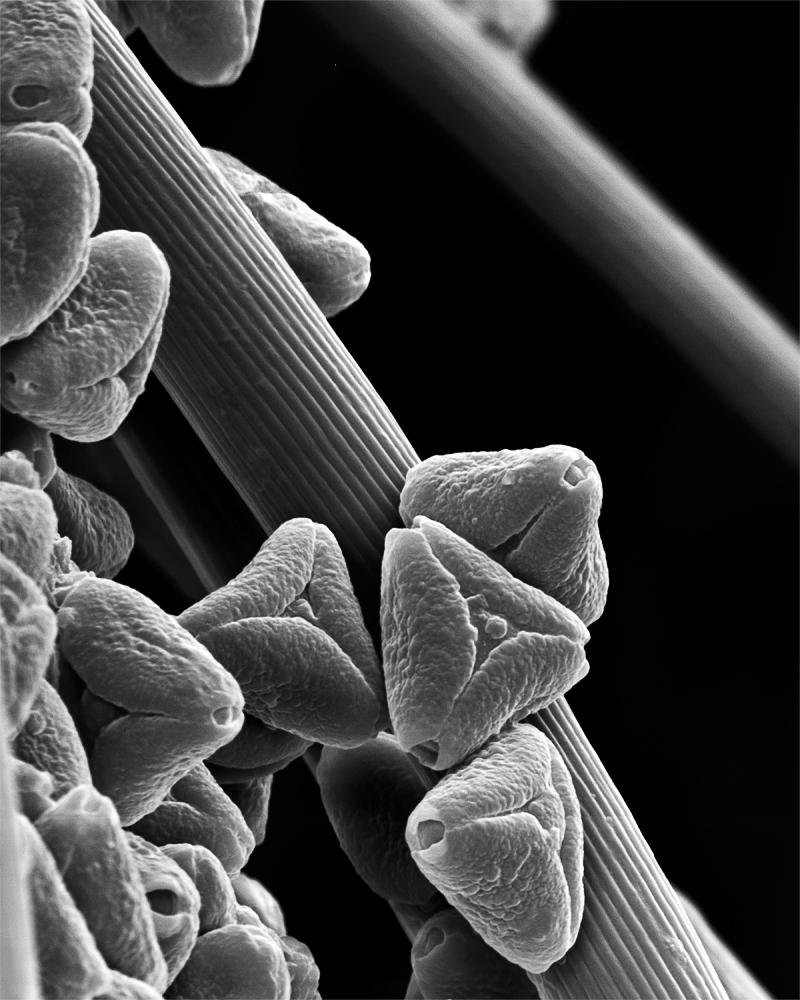

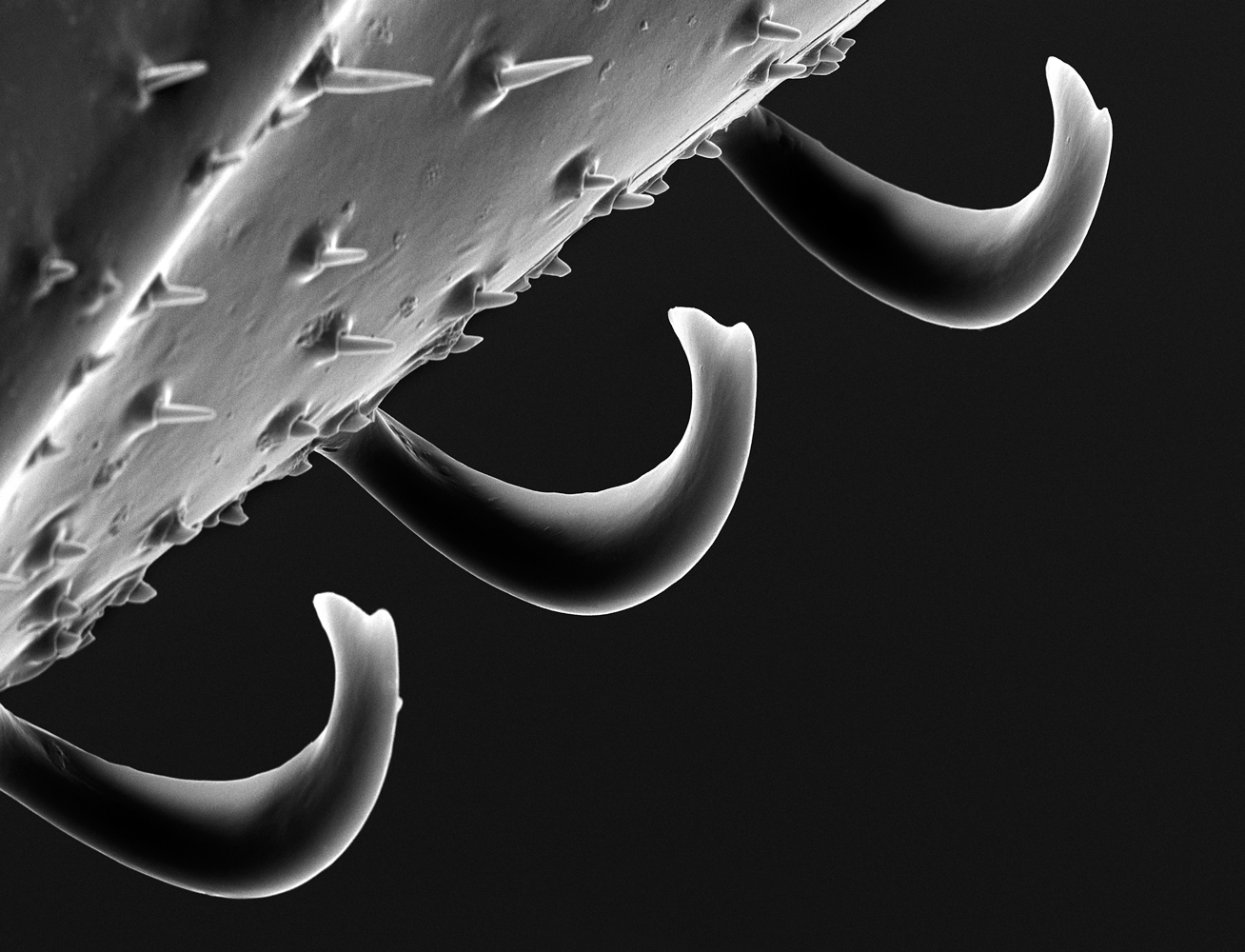

The sight helped inspire Fisher to begin a multi-year project centered on highly composed photographs of bee parts magnified through the scanning electron. The results reveal the intricate complexity that makes up something as seemingly simple as bee. Magnified 800 times, the invisible hairs that sprout from a bee’s eyes looks like a forest, with fat cells of pollen trapped between the branches. Magnified 150 times, the segments of the finely jointed antenna all pop visibly: the pollen-covered scape, the knob-shaped pedicel and the flagellum. Each of the 6,900 hexagonal lenses is visible in the eye, magnified 200 times, as if the visual organ were a futuristic chessboard. Magnified 600 times, the bee’s proboscis—the spoon like tip of the tongue that flicks out to absorb nectar, water and honey, seems otherworldly.

As Verlyn Klinkenborg writes in his introduction to Fisher’s book, Bee, “there’s nothing general about a honeybee”—and her photographs bear that out. Every part of the bee’s body is seemingly designed to further its specific purpose: to make its way into the world, to capture pollen and carry it back to the hive, even to die in its defense with a stinger that, when employed, rips out the bee’s own innards. “As though revealing a secret, the scanning electron microscope presents a realm of structure, design and pattern at a level of intricacy we are oblivious to in our daily experience,” writes Klinkenborg. Fisher’s photographs make visible that microscopic symmetry.

But while the honeybee may be perfectly suited to its purpose, the world around the insect is changing—and not for the better. Bees are bombarded with pesticides, beset by deadly mites in their hives, sickened with new diseases and starved of nutrition as the fields they pollinate are replaced with rows of monocultured corn and soybeans. The bees are dying, and our actions—conscious and unconscious—are at fault. “We’re so out of balance,” says Fisher. “They’re the canaries in the coal mine.” More than that, there’s a connection between the bees and us, a connection that goes beyond the simple fact that the pollination work of the honeybee puts food on our tables. We’re part of the same world, from the “microscopic to the cosmic” as Fisher puts it—and we need to keep that world together.

Subscribe here to read Bryan Walsh’s full TIME cover story on A World Without Bees. Already a subscriber? Read it here.

Rose-Lynn Fisher is a fine-art photographer. Her book, BEE, is available through Princeton Architectural Press.

Bryan Walsh is a senior editor for TIME International & environmental writer. Follow him on Twitter @bryanrwalsh.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com