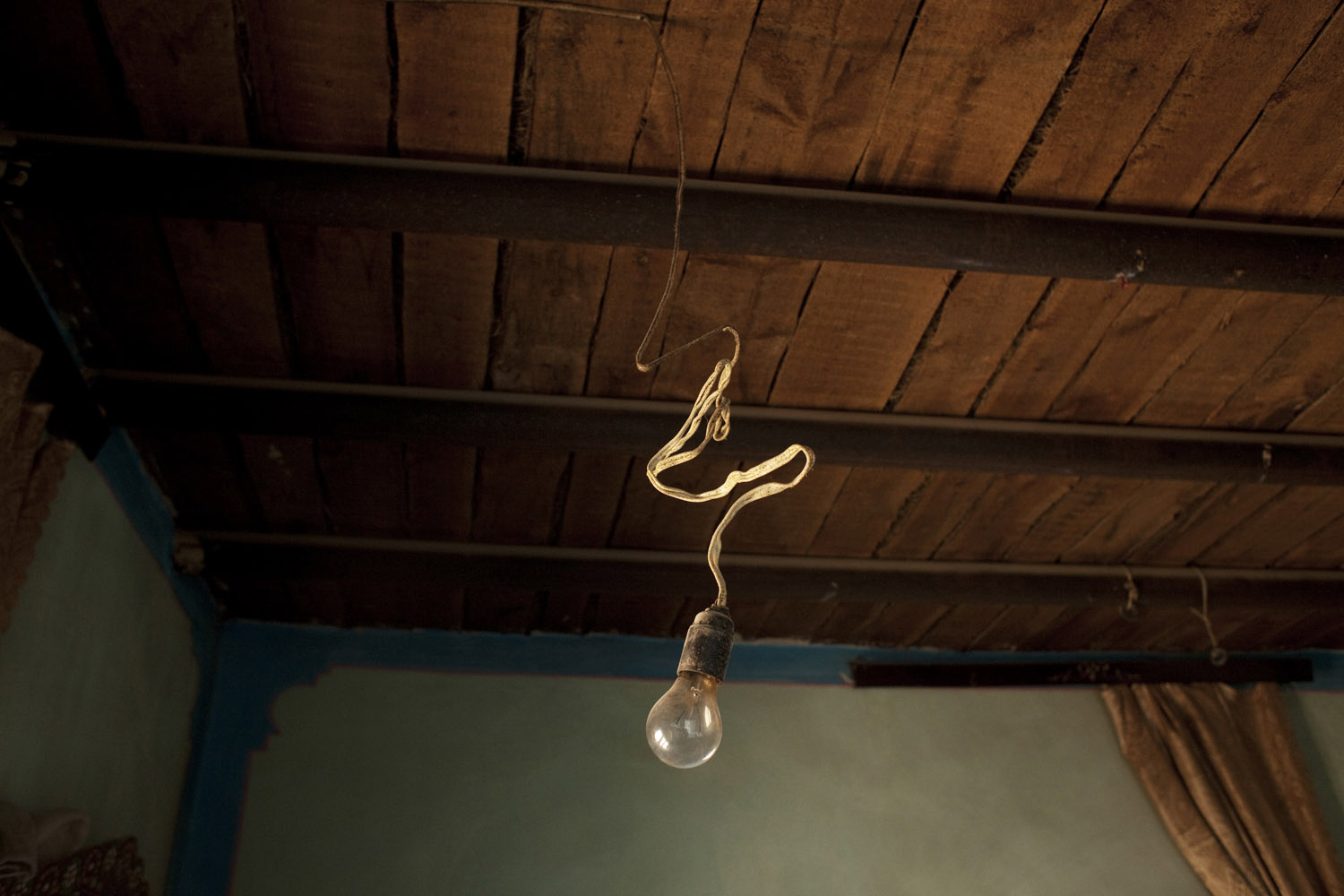

The land between the Amu Darya and Syr Darya, the rivers the ancient Greeks knew as the Oxus and Jaxartes, serves for many of us as the ultimate flyover territory as we jet from Europe to Asia and beyond. Carolyn Drake, an American photographer who has worked for TIME, the New Yorker and National Geographic, spent five years and 15 trips roaming this expanse of Central Asia, documenting a hardy people who survived on the fringes of empires Russian and Chinese. From her travels to places with Tolkien-esque names—Osh, Termez, Kokand—comes a photography book called Two Rivers. It is a surreal and improbably luminous work, leavened by the kind of humor that flourishes in the harshest of places.

The land between the two rivers once supported fishing ports and fertile farms. But the ecological aggression of the Soviets, not to mention the toll of global warming, has robbed the region of liquid and life. Boats are now marooned on earth, livestock parched. Always there is dust. Raised in coastal cities and most comfortable when the horizon ends in a confluence of sea and sky, I find the aridness unsettling. Yet Carolyn captures the counterpoints to the landlocked breadth: a dirty puddle, a rush of irrigation water, a murky pool embellished with Olympic iconography.

If the Inuits, perhaps apocryphally, have dozens of words for snow, surely the peoples of Central Asia living in present-day Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan must know how to distinguish between so many shades of brown: the salt flats of what once was the Aral Sea; the rusting machinery of the Soviet planned economy; the matted wool of a dirty sheep; all those deserts with all that sand; the stalks of cotton plants that suck up scarce water; the nuts and flatbread Central Asians offer up with their boisterous hospitality.

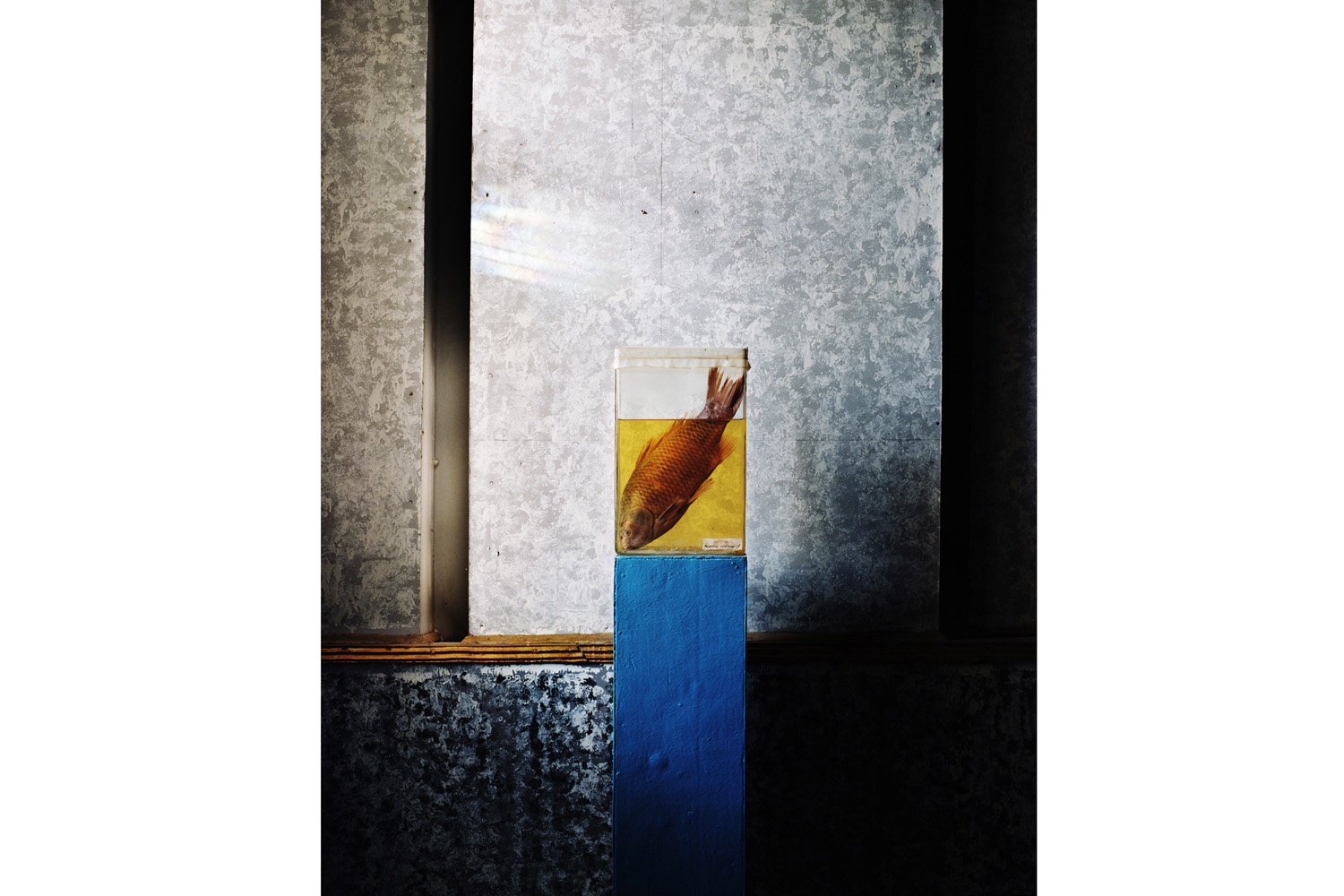

Yet even in this sere landscape, Carolyn displays an appetite for color that’s bold, maybe even defiant. There is the exuberant overlay of patterns that Central Asian women assemble as they dress each morning. We are treated to turquoise doorframes, the plumage of a freshly killed duck on white tiling and the burnt umber of an aged Moskvitch car from which a sad-eyed man stares out. Gaudy packages are used to smuggle heroin. Near the source of the two rivers, Carolyn gives us the frozen white of the Tianshan Mountains—I wonder what word the Inuits have for this particular manner of snow? And there is, of course, the visual assault of the monuments to ego built by post-Soviet dictators, whose love of gilt, marble and ever-flowing fountains underlines the paucity of the surrounding land.

One afternoon in mid-2011, when Carolyn and I were working together on a story in far western Kazakhstan, we wandered behind an oil refinery on the outskirts of Atyrau. A network of run-off canals extended into the desert, the water startlingly limpid despite the unseen chemicals. Ethnic Russians,with limp, sandy hair and sunbaked torsos, lounged among the cattails, drinking vodka and fishing for the kind of small, hardy creatures that seem to thrive amid pollution. The placid scene I replay in my mind recalls the best qualities of Carolyn’s photographs: strange, even toxic oases in which people find pleasure because what else is there to do but celebrate what little the land has given them?

Carolyn Drake began photographing Two Rivers in 2007, traveling frequently from her base in Istanbul. The work was funded in part by a Guggenheim Fellowship and was a finalist for the Santa Fe Prize. With text by Elif Batuman, the book was self-published in June 2013.

Hannah Beech is TIME’s China bureau chief and East Asia correspondent.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com