For more than four decades photographer Camilo José Vergara has devoted himself to documenting history. His work—often focused on the poorest and most segregated communities in urban America—strives for objectivity and speaks directly about reality and how it changes over time. Vergara’s dedicated and meticulous approach—in which he has returned to the same locations at regular intervals over the years to document their decay (and sometimes renewal)—has often been a solitary and dogged one.

While his work has not yet received the acceptance of the gallery world, he can be considered one of the most important photographic documentarians of his age. Vergara’s photography has found support from museums and historical societies, earning him a MacArthur fellowship in 2002. This week, Vergara’s unique and enduring work will be recognized at the White House where President Obama will present him with the National Humanities Medal. He is the first photographer ever to receive the honor. Here, he writes for LightBox about his work.

Recent revelations about the astonishing scale of governmental snooping by America’s National Security Agency (the NSA) begs some rather troubling questions. Are photographers today leaving the recording of history — and thus the telling of history — to an exponentially growing number of surveillance cameras, to governmental spy programs and to social-media behemoths like Facebook, Instagram and Google? Or, perhaps even more dismaying, have photographers ceded control over the visual narrative of their time to high-end photography books that either aestheticize their subjects or rely solely on pictures culled from historical archives?

The most distinctive characteristic of my own work is the way in which I combine my photographs with both precise data and sociological analysis. My archive, while vast, is slim in comparison to the immense number of images found in online image banks, yet it has the virtue of possessing a genuine continuity over time; it includes the voices of my subjects; and it features my observations about the look and feel of the places I document, as well through the results of historical research.

As MIT Professor Anne Whiston Spirn has said of photography, it “can be a way of thinking about landscape, a means to read a landscape, to discover and display processes and interactions, and to map out the structure of ideas.” As a medium of inquiry, photography is, ultimately, “a disciplined way of seeing.”

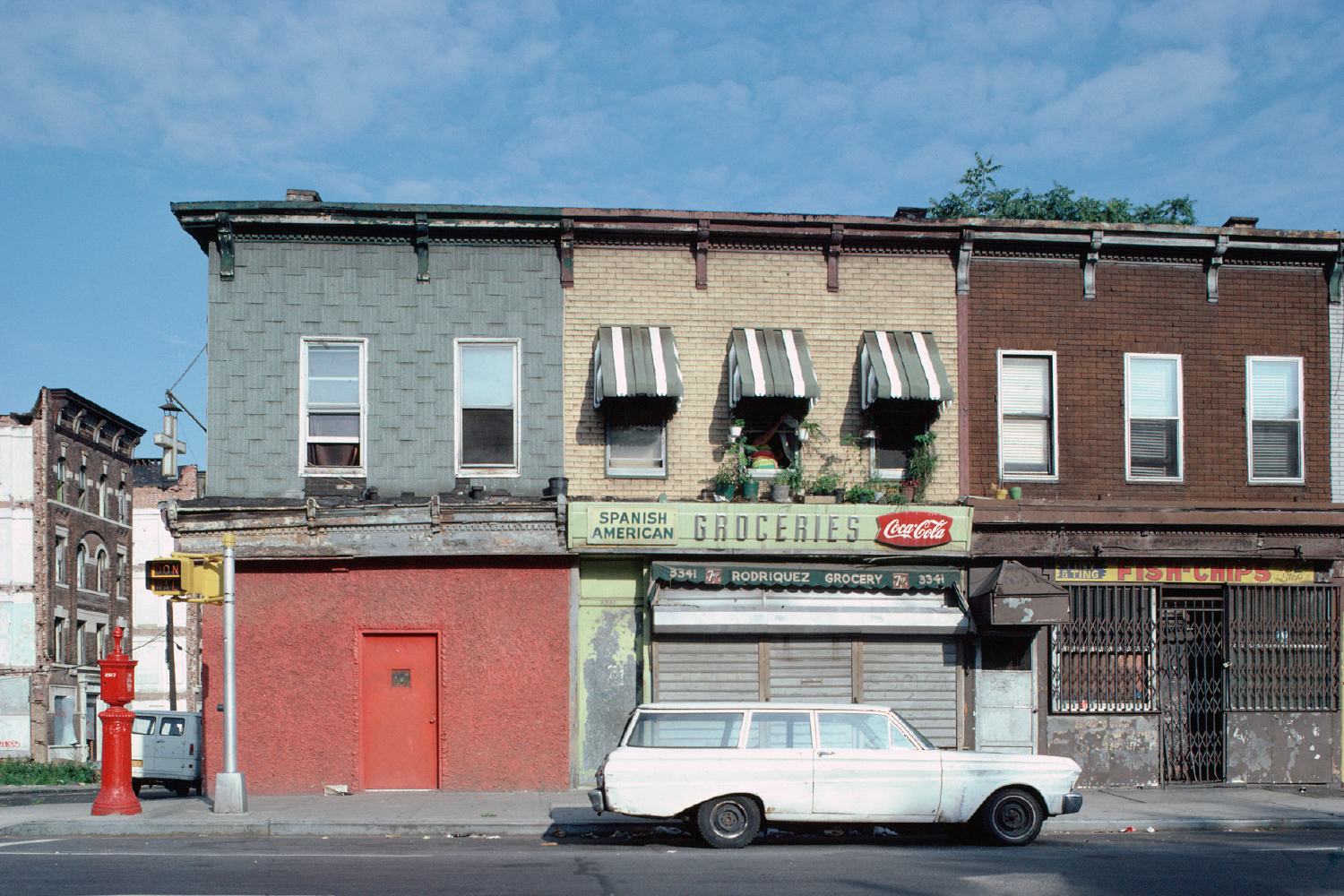

For more than four decades I have devoted myself to photographing and systematically documenting the poorest and most segregated communities in urban America. My focus is on established East Coast cities such as New York, Newark and Camden; rust belt cities of the Midwest like Detroit and Chicago; and such West Coast cities as Los Angeles and Richmond, California.

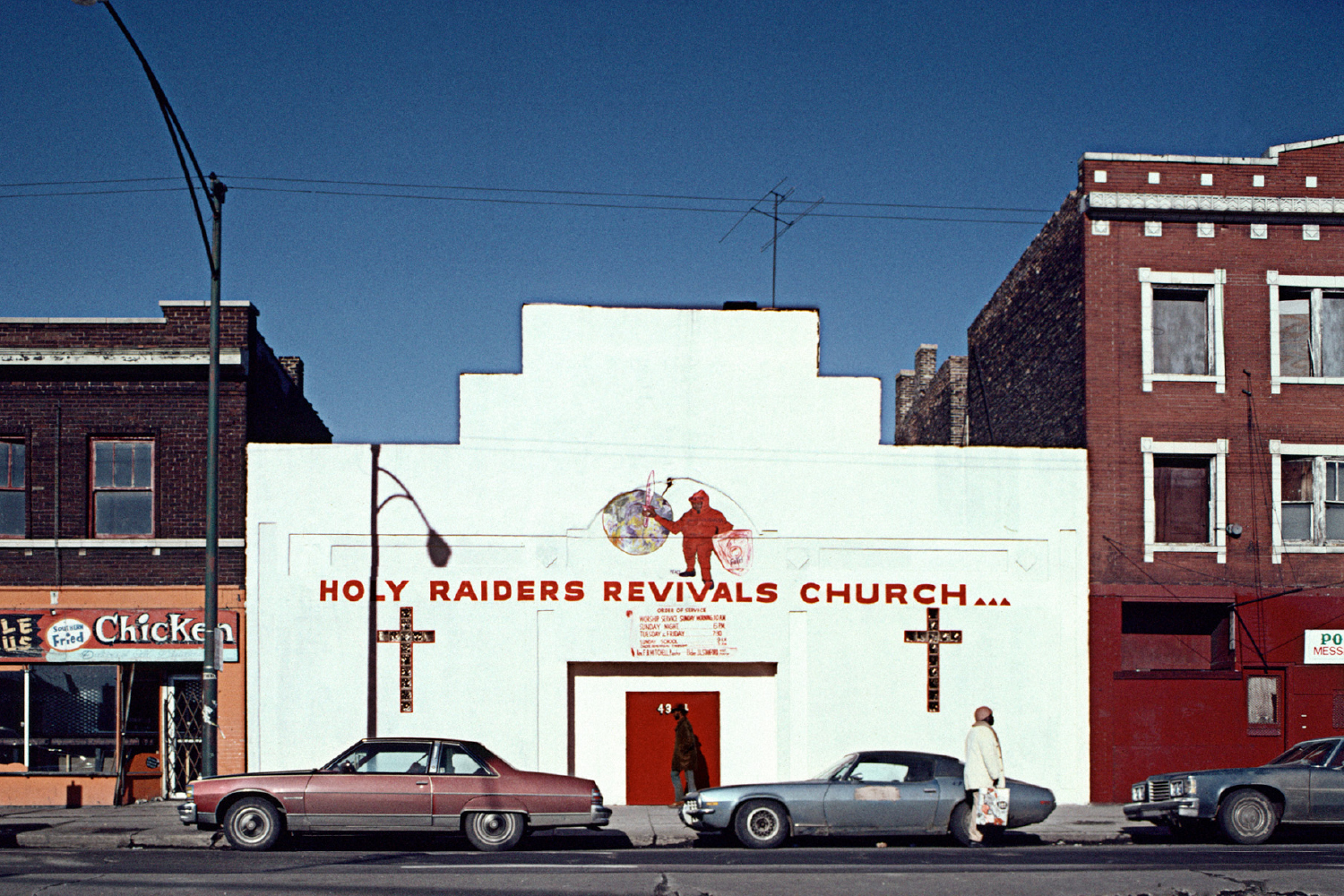

I began my documentation in the tradition of such masters as Helen Levitt, Walker Evans and Henri Cartier-Bresson, for all of whom the human figure was integral to their work. But increasingly, I became drawn to the urban fabric of America’s poor inner cities — to the buildings that composed it and the life and culture embedded in its structures and streets.

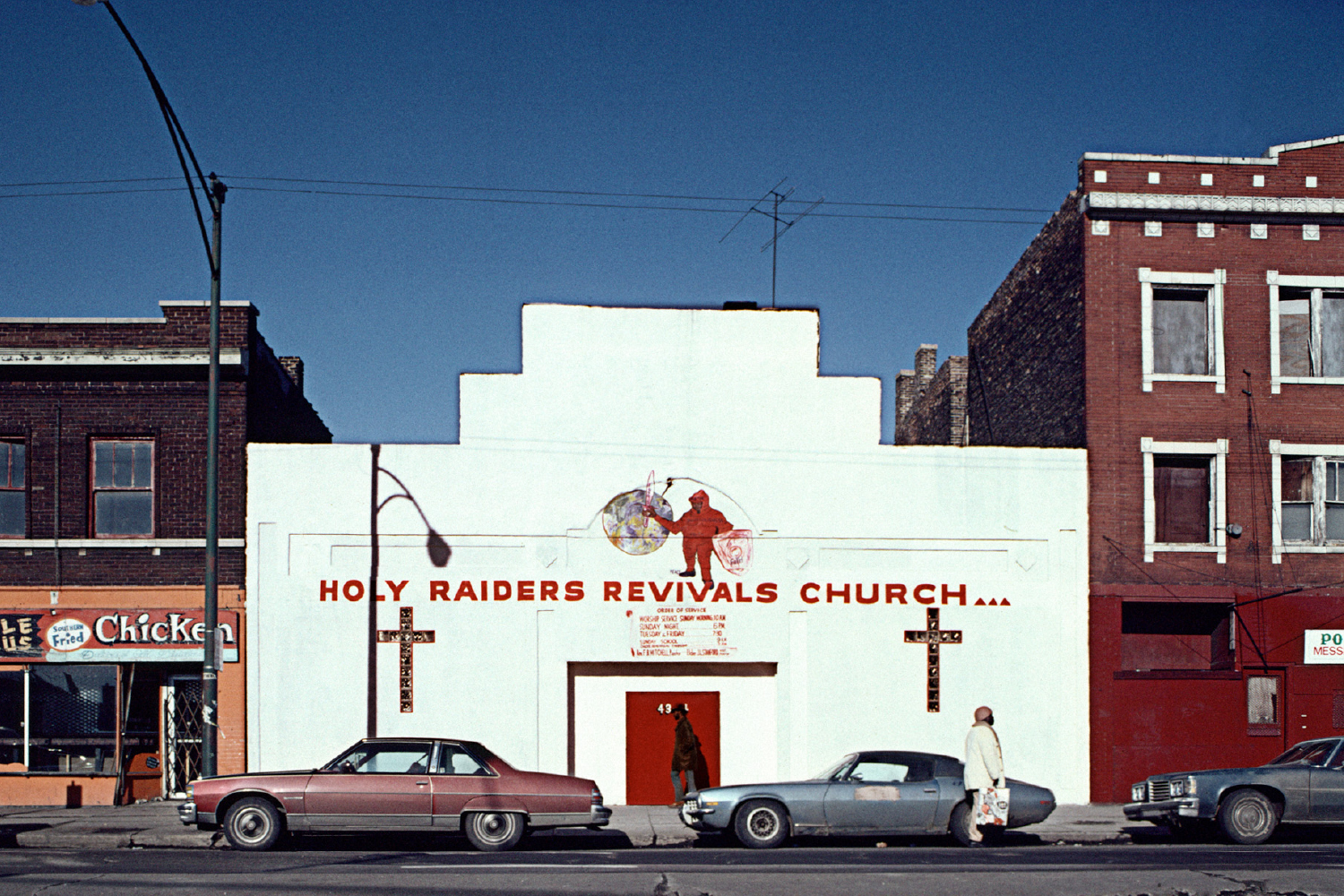

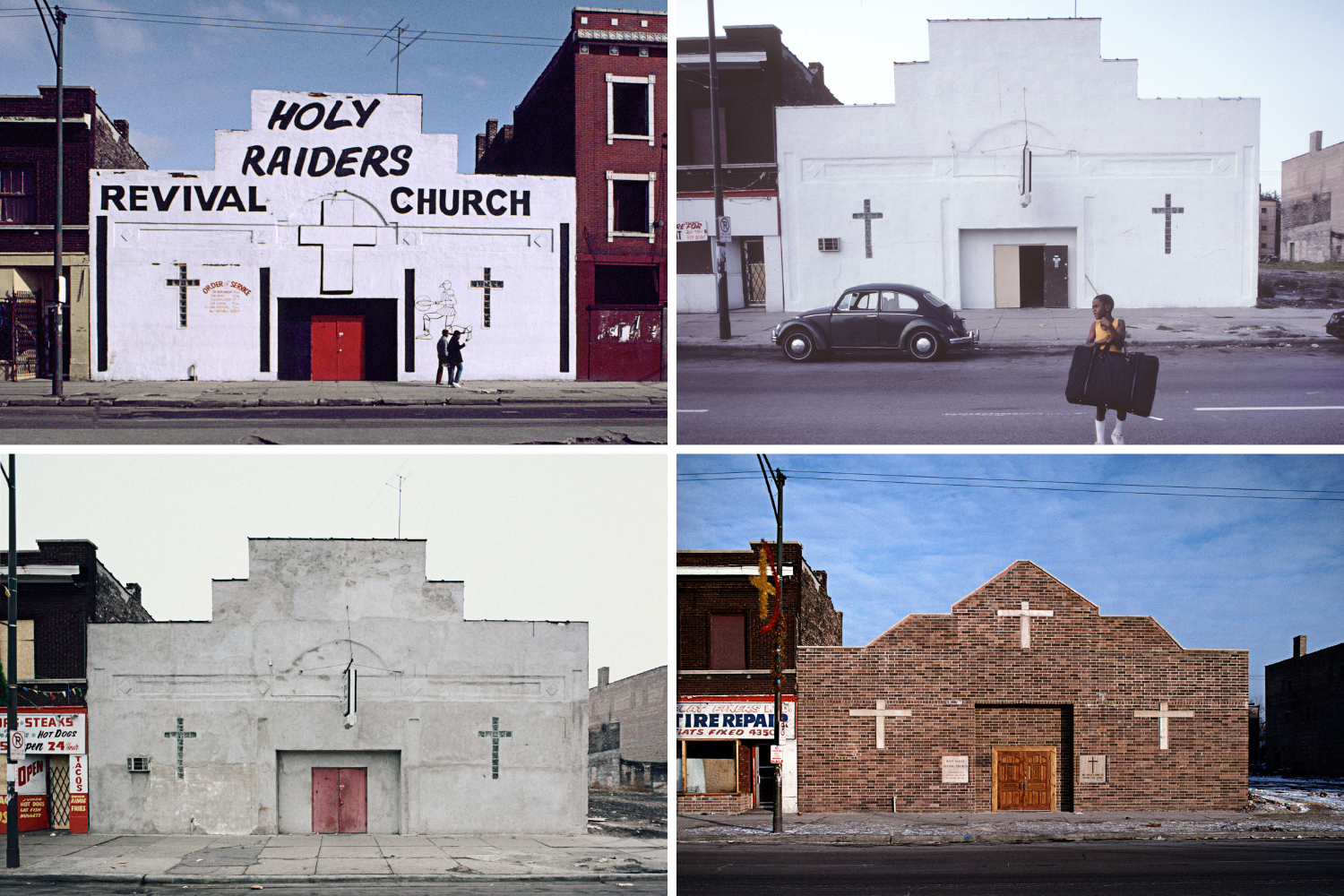

Not wanting to limit the scope of my documentation to places and scenes that captured my interest merely because they resonated with my personality, I have struggled to make as complete and objective a portrait of America’s inner cities as I could. Thus, I developed a method to document entire neighborhoods and then to return year after year to re-photograph the same places over time and from different heights, blanketing entire communities with images. Along the way I became a historically conscious documentarian, an archivist of decline, a photographer of walls, buildings and city blocks.

Bricks, signs, trees and sidewalks have spoken to me the most truthfully and eloquently about urban reality. For me, a people’s past, including their accomplishments, aspirations and failures, are reflected less in the faces, postures and clothing of those who live in these neighborhoods than in the material, built environment in which they move and that they modify over time. Photographs taken from different levels and angles, with perspective-corrected lenses, form a dense web of images, a visual record of these neighborhoods over years and even decades. I write down observations, interview residents and scholars, and make comparisons with similar photographs I have taken in other cities.

Studying my growing archive, I discover fragments of stories and urban themes in need of definition and further exploration. Some areas decline as longtime businesses give way to empty storefronts, graffiti and garbage, while others gentrify, with corporate chain stores replacing local mom-and-pop enterprises. I capture the ever-vital street life of neighborhoods, from stoop gatherings and parades to murals memorializing drug dealers, rappers and great leaders who are especially admired in such neighborhoods. I also look for the new shapes of old businesses, of emerging new ones and of new uses for old places. Wishing to keep the documentation open, I include places such as empty lots, which as segments of a temporal sequence are often especially revealing.

After 2000 my documentation entered a new phase. I began to do online searches of words, themes and addresses. With a simple Google search for a particular location, I was able to find newspaper and magazine articles, religious pamphlets, student papers and announcements for conferences and political meetings, all of which enriched the content of my research and prompted me to ask fresh questions and take new photographs. I discovered information about people who lived in the locations I photographed, read about events such as crimes, fires and stores and institutions coming to or abandoning neighborhoods, and learned about historical events that had taken place nearby. After the appearance of Google Maps (2005) and Google Street View (2007), these too became important research tools, allowing me to revisit the locations of my photographs and to go beyond the frames of the images to explore the streets around them. Whenever in doubt about the location of an image, I search for the correct address with Google Satellite or Street View.

I see photography as a medium that spurs continuous inquiry and thus leads to greater understanding of the spirit of a place. I think of my images as bricks that, when placed in context with each other, reveal shapes and meanings within these often neglected urban communities. Through photography, I have become a builder of virtual cities.

My hope is that my long-term records will become part of our collective urban memory.

Camilo José Vergara is a 2002 MacArthur fellow whose books include American Ruins and How the Other Half Worships. LightBox has previously featured his work on MLK Murals, the World Trade Center and Everyday Life in the Hood: New York 1970 – 1973. You can see more of his photos on his web site and can contact him at camilojosev@gmail.com.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com