For a man who worked professionally for barely more than ten years, Sergio Larrain, who died in 2012, had a disproportionately large impact on photography. The author of four books, he is widely considered Chile’s finest lensman, though he became something of a recluse later in life.

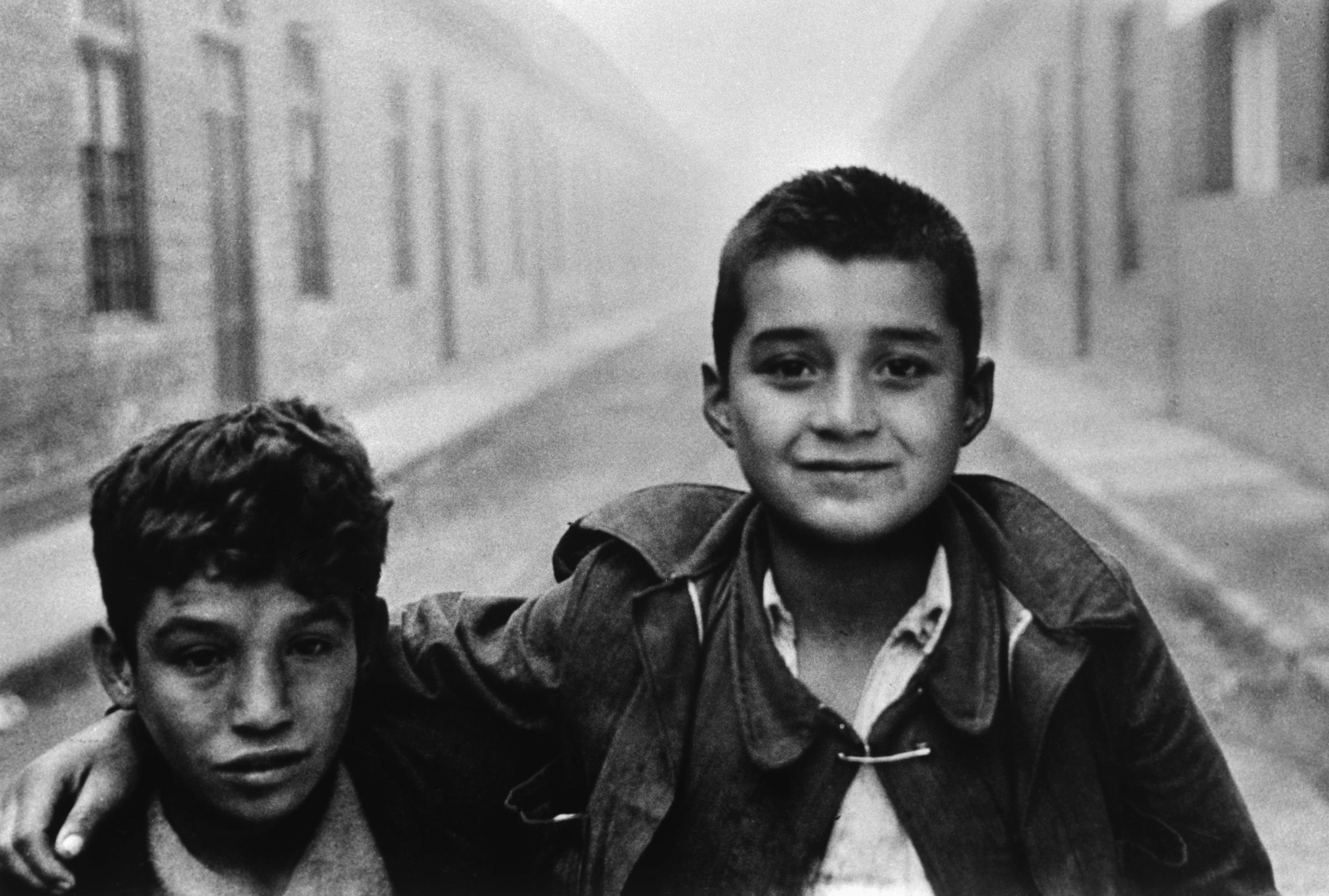

Born in Santiago into a well-to-do family, he ditched a possible career in forestry for a life behind the camera, and saved up for his first Leica by working in a cafe. The son of an architect father, his love of photography grew when he later traveled the Middle East and Europe, lens in tow. His real break came in 1958, though, when he bagged a British Council bursary that allowed him photograph cities throughout the U.K.

The images that emerged – chiefly of London – were captivating shots of the everyday, and caught the eye of Henri Cartier-Bresson. The Frenchman later invited Larrian to Paris and the Chilean soon joined Cartier-Bresson’s Magnum agency as an associate in 1959 (and became a full member in 1961).

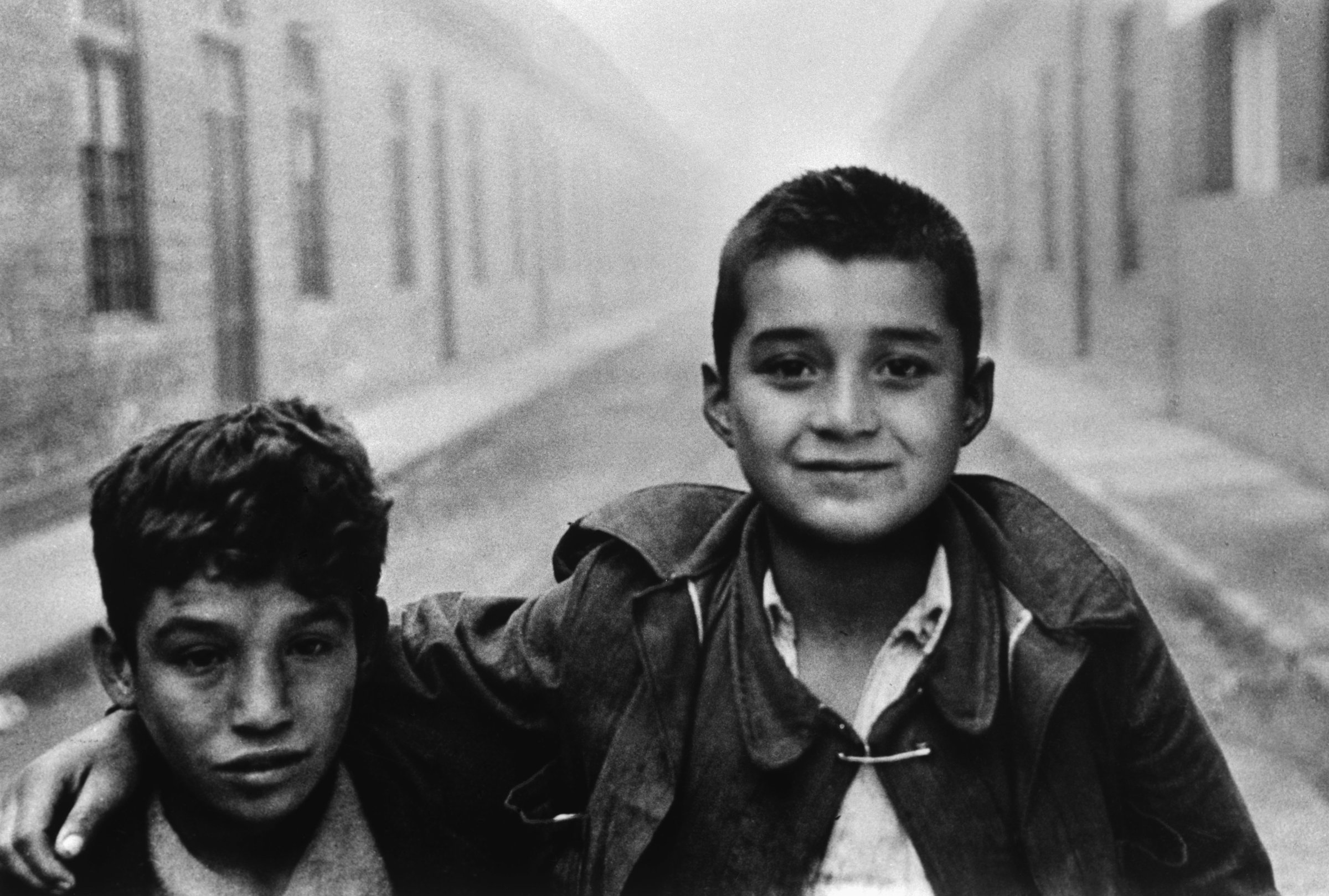

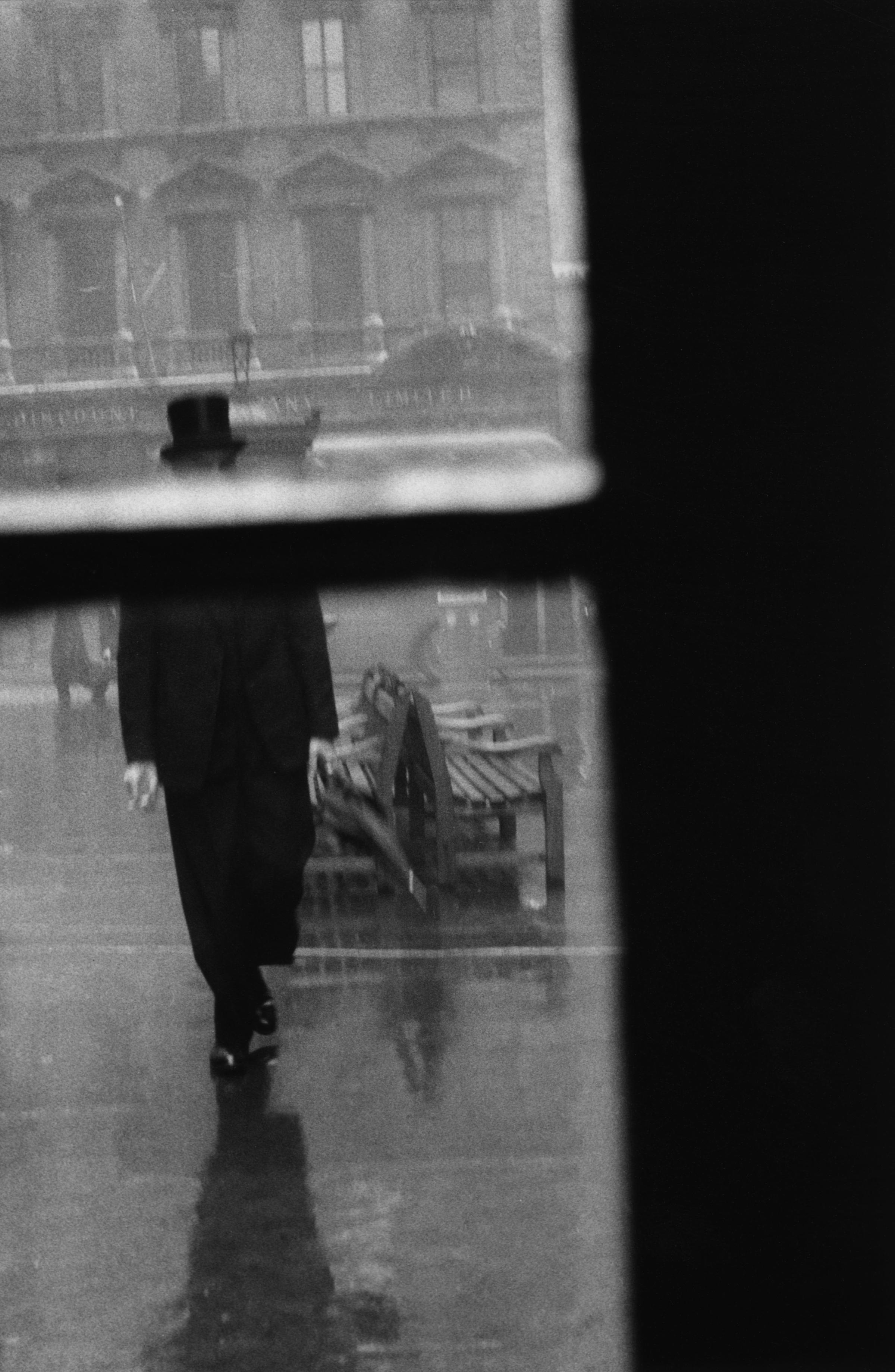

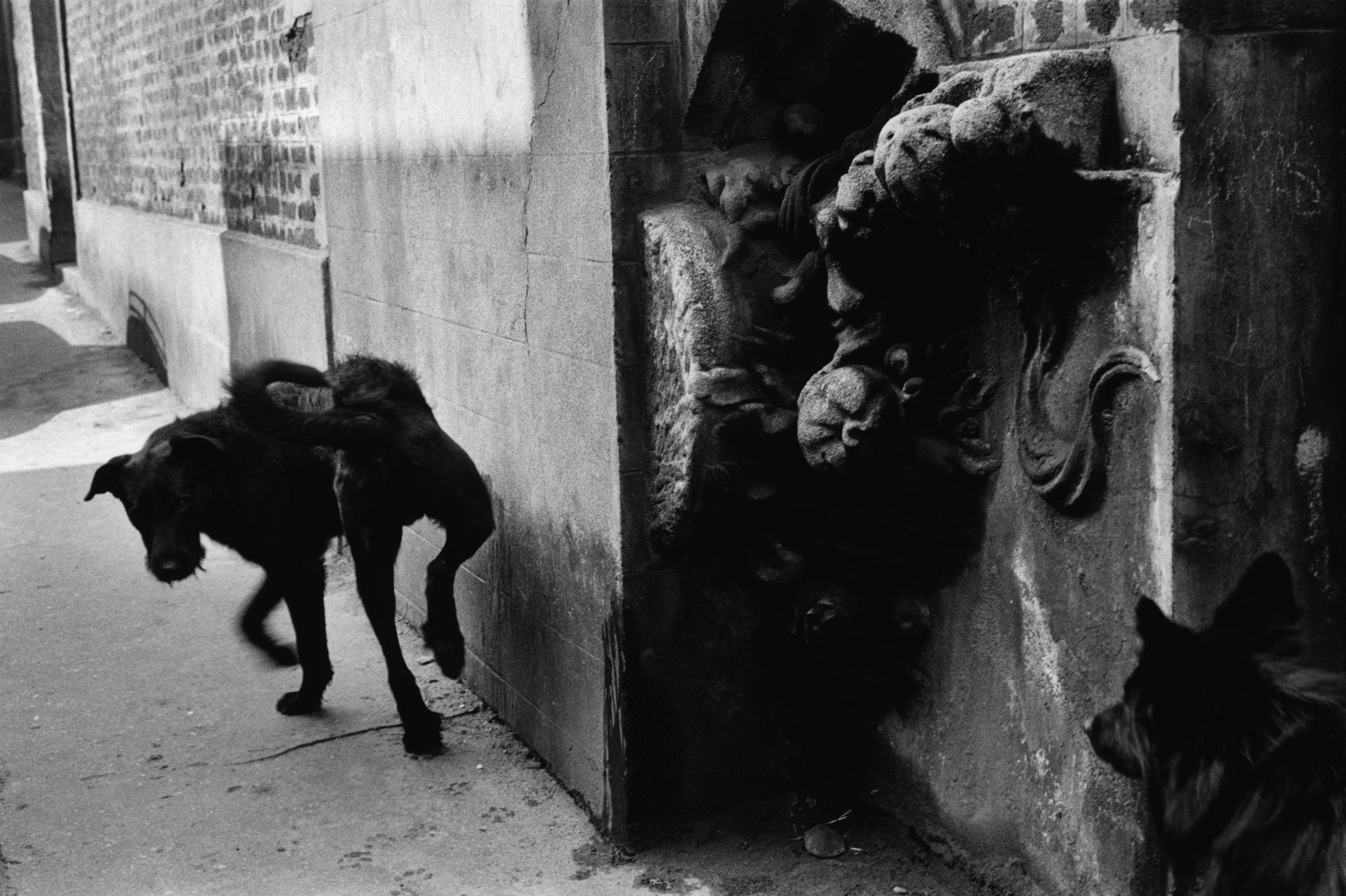

His was a career filled with disparate subject matters, tied together with his famous compassion for those he photographed. Larrain’s style is immediately recognizable: he made use of vertical frames, was a fan of low angle shots and was wholly unafraid of experimentation. Much of his work was concerned with street children, and his some of his earliest pictures – those from a 1957 series in Chile, for example – are certainly his most powerful. Though he was no stranger to architectural photography, having shot fellow countryman and diplomat Pablo Neruda’s house.

Indeed, his portraiture is as humanistic as it is environmental. One of his most captivating images, taken as part of the later Valparaiso series in the port city of Valparaiso, Chile, perfectly combines both. The piece shows two young girls going down a staircase, their delicate frames contrasting with the solid, modernist-seeming gray concrete surrounding them. It is a picture as much about its subjects as it is about the context in which see them; and with their backs turned to us, is as much about what we see as what we don’t.

“He is very different, very intense,” says Agnès Sire, director of the Henri Cartier-Bresson Foundation, and curator of an upcoming retrospective of Larrain’s work at Les Rencontres d’Arles, “for me, he is [often] interested in what you don’t see.”

Larrain stopped taking pictures professionally in the 1970s and retreated to the Chilean countryside for a life of calm meditation (though he continued to take some pieces in the 1980s, they were photographs of objects, usually in his house, which he would send to friends in the mail). It is said that he withdrew because he, ever the humanitarian, became disillusioned with the often harsh world he was photographing, and felt powerless to help.

“He stopped his career. It was not bringing him what he [thought] it would bring to him,” explains Sire. “[He felt] the fact he photographed those kids will not change the fact that there will always be kids abandoned. Photography will not help save the planet.”

Sire adds that Larrain even rejected the idea of retrospectives for most of his later life, because they might force him out of his self-imposed retreat, and that his career was meteoric for a reason: he was a man who would only, and could only, follow his instincts. “He was unique,” she says, “he was really a free man.”

A retrospective of Sergio Larrain’s work forms part of Les Rencontres d’Arles 2013, which runs from July 1 through Sept. 22, 2013.

Richard Conway is a member of TIME.com’s photo staff. He’s previously written for LightBox on Erwin Olaf, Gary Winogrand, Ezra Stoller and Pete Hujar.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com