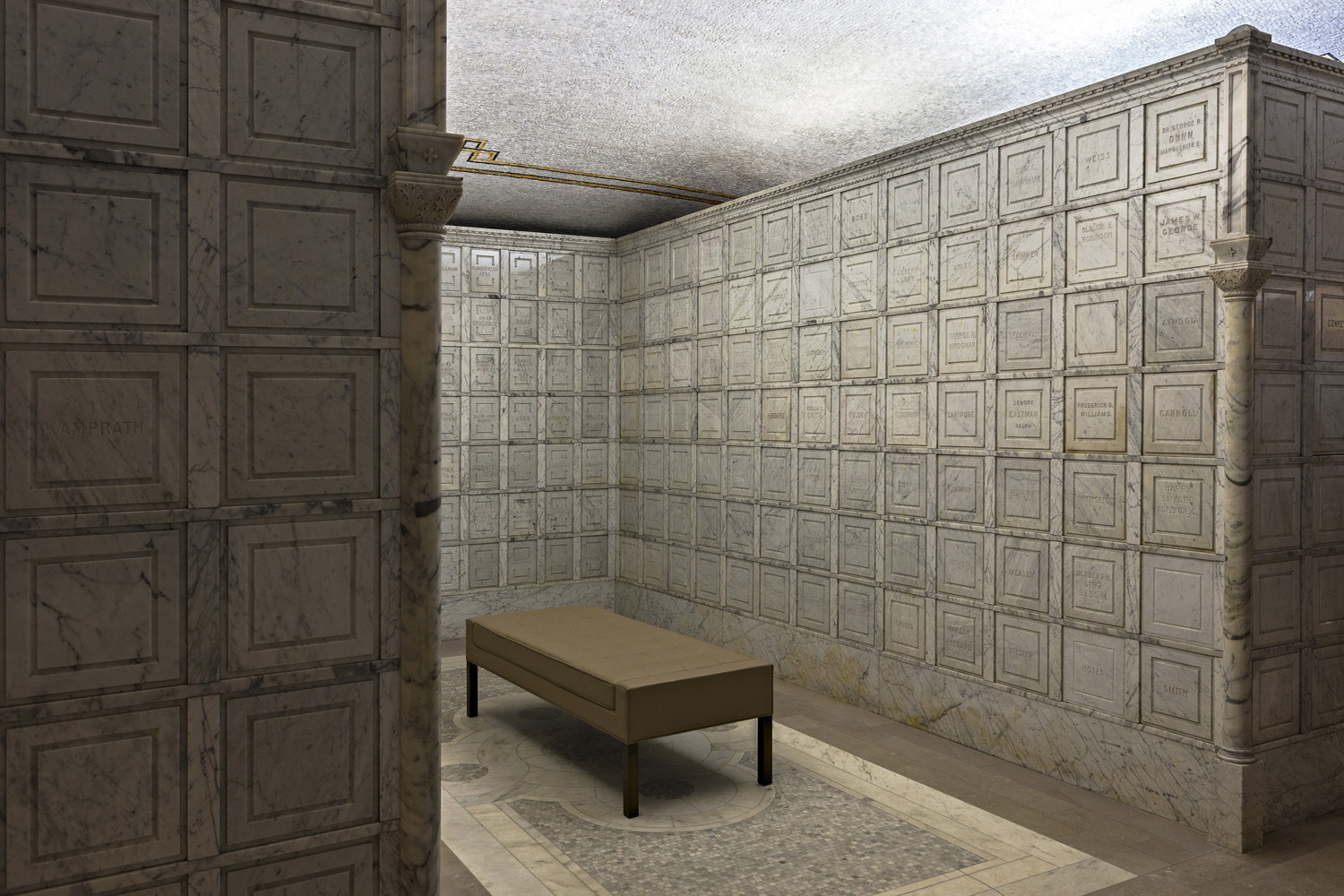

Swedish photographer Lars Tunbjörk has documented frenzied consumerism, the soul-deadening effects of office life and the strange theatrics of U.S. politics, always displaying a sense of humor and a grasp of the absurd that would not be out of place in a George Saunders short story. For our feature on the increasing popularity of cremation around the country, TIME sent Tunbjörk deep into the American heartland to chronicle the goings-on at three separate crematories.

For decades, burial has been by far the most common form of disposition in the United States. Most Americans never gave it a second thought: their grandparents were buried; their great-grandparents were buried—it just made sense that they’d get buried, too, in the family plot, beside their closest relatives.

(Click here to read TIME’s special report on cremation and find out why our changing attitude toward this final rite of passage says everything about the way we live now.)

But today we’re a far different society than we were just a few decades ago. Within the next few years it’s projected that, for the first time, more Americans will get cremated than buried.

Much of the recent rise of cremation’s popularity can be credited to the Great Recession. Cremations can cost as little as a quarter as much as traditional burials. But it’s not just the price tag that makes cremation a popular alternative.

For one, we’re a much more mobile society today. We don’t buy family plots the way we used to because more of us get an education, start a family, get a job and retire far from our birthplaces. When it comes time to find a final resting place, transporting an urn is much easier than dealing with a casket.

Historically, the U.S. has been a majority Christian nation, and Christianity favors burial for a number of reasons. But Americans are becoming increasingly secular and many of us now identify as atheist, agnostic or, even if we consider ourselves religious, aren’t affiliated with a particular faith. That separation from a religion with ties to traditional burial has led to more Americans exploring other options of disposition.

Cremation has also appealed to those looking for a more eco-friendly solution than burial, which involves placing a body filled with embalming fluids on a plot of land that will need to be maintained in perpetuity. And while flame-based cremation is a more environmentally sensitive solution than traditional burial, a new breed of eco-friendly cremations is just starting to become popular. “Green cremations,” which use a mixture of water and potassium hydroxide, are available in a handful of states and are outpacing flame-based cremations in the areas where they’re offered.

The practice of cremation will in all likelihood only grow as we become more mobile, secular and eco-conscious as a society. In fact, in the not too distant future, burial might well be seen as a peculiar option in light of the eminently reasonable, less expensive and environmentally sound method now so widely available—and increasingly embraced.

Click here to read TIME’s special report on cremation and find out why our changing attitude toward this final rite of passage says everything about the way we live now.

Lars Tunbjörk is a photographer based in Stockholm. He previously photographed the 2012 Iowa Caucuses for TIME.

Josh Sanburn is a writer/reporter for TIME in New York. Follow him on Twitter @joshsanburn.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com