Variously characterized as the “private land of God,” the “land of flowers” and the “diamond” of the subcontinent, the state of Kerala—perched on the southwestern tip of the Indian peninsula—is renowned for breathtaking landscapes and, in contrast to much of South Asia, an uncommonly high standard of living. Despite enjoying India’s highest life expectancy and literacy rates, however, Kerala also struggles with staggering numbers of homeless, alcoholics and suicides. The rate at which someone takes his or her own life in Kerala is three times the national average. These blots on an otherwise near-flawless reputation have puzzled researchers for years.

“The rapid economic development has left many people behind and amplified social taboos,” photographer Paolo Marchetti tells TIME. “All of these problems are really linked together—single pages of the same book.”

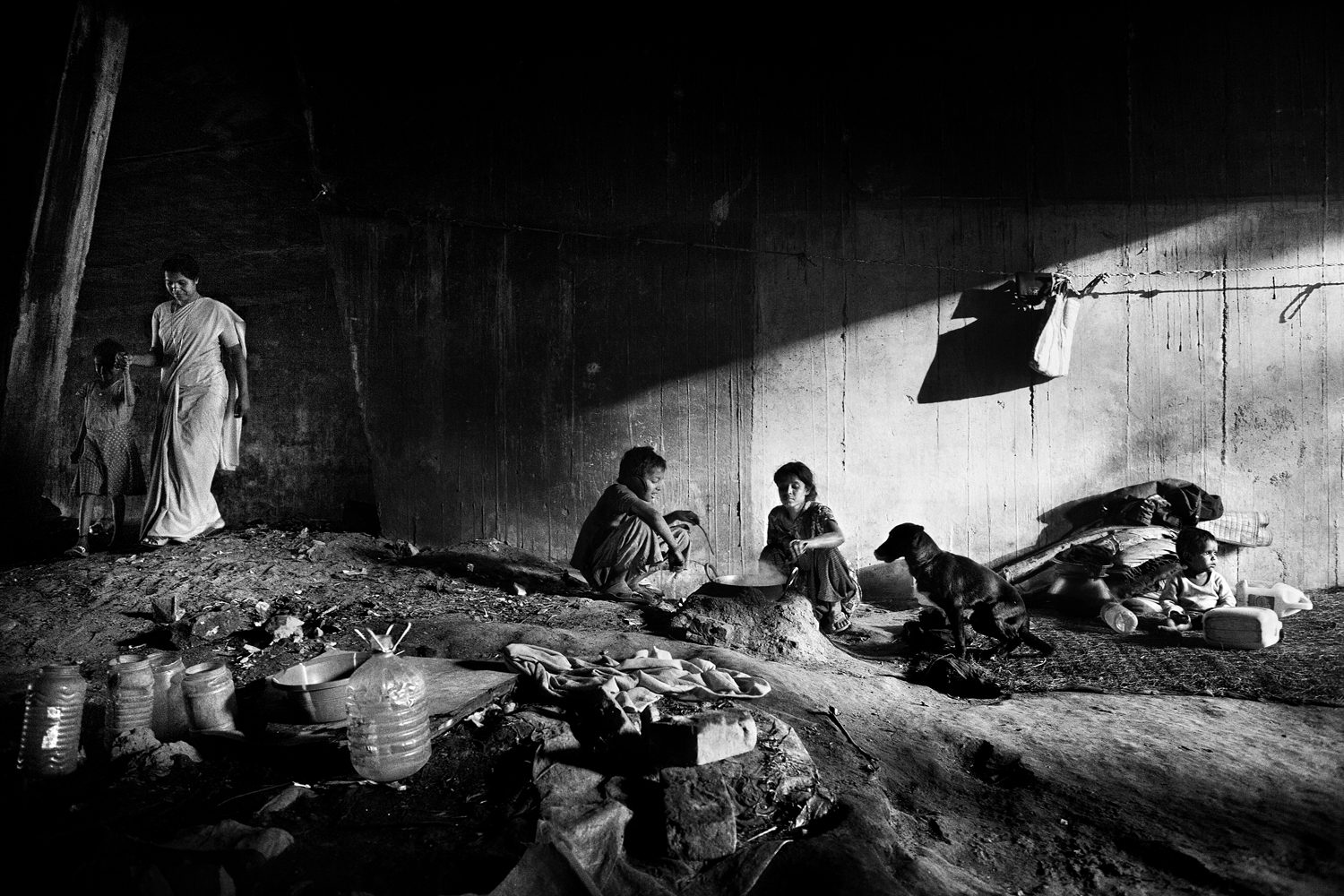

In 2009 and 2011, the Italian photojournalist traveled to India, embedding himself in NGO orphanages and mental hospitals, in slums and bars peopled by the most marginalized populations of Kerala, abandoned by family and government. He photographed children born out of wedlock, alcoholics and the (supposed) mentally ill. In the process he captured the complexities inherent in development and, especially, the clash of new opportunities and old traditions.

In Kerala, where reputation rules, “the good name of the family,” Marchetti says, “determines one’s ability to integrate into society at every level—professional and especially marital. [One’s reputation] has to be something clean, something limpid.”

Many of the problems he explored, he says, can be traced to the traditional market rules of marriage—essentially an economic transaction managed by the head of the household and one that necessitates proof of a healthy lineage.

“The abandonment of a relative is a common practice, a response to the least manifestation of a mental deficiency or dependence on alcohol,” he says, “some little problem, problems that in our society we have every day.”

“It’s not necessary to be—forgive my word—mad, to be crazy,” he adds. “Depression, for instance, this is enough to be abandoned on the streets.”

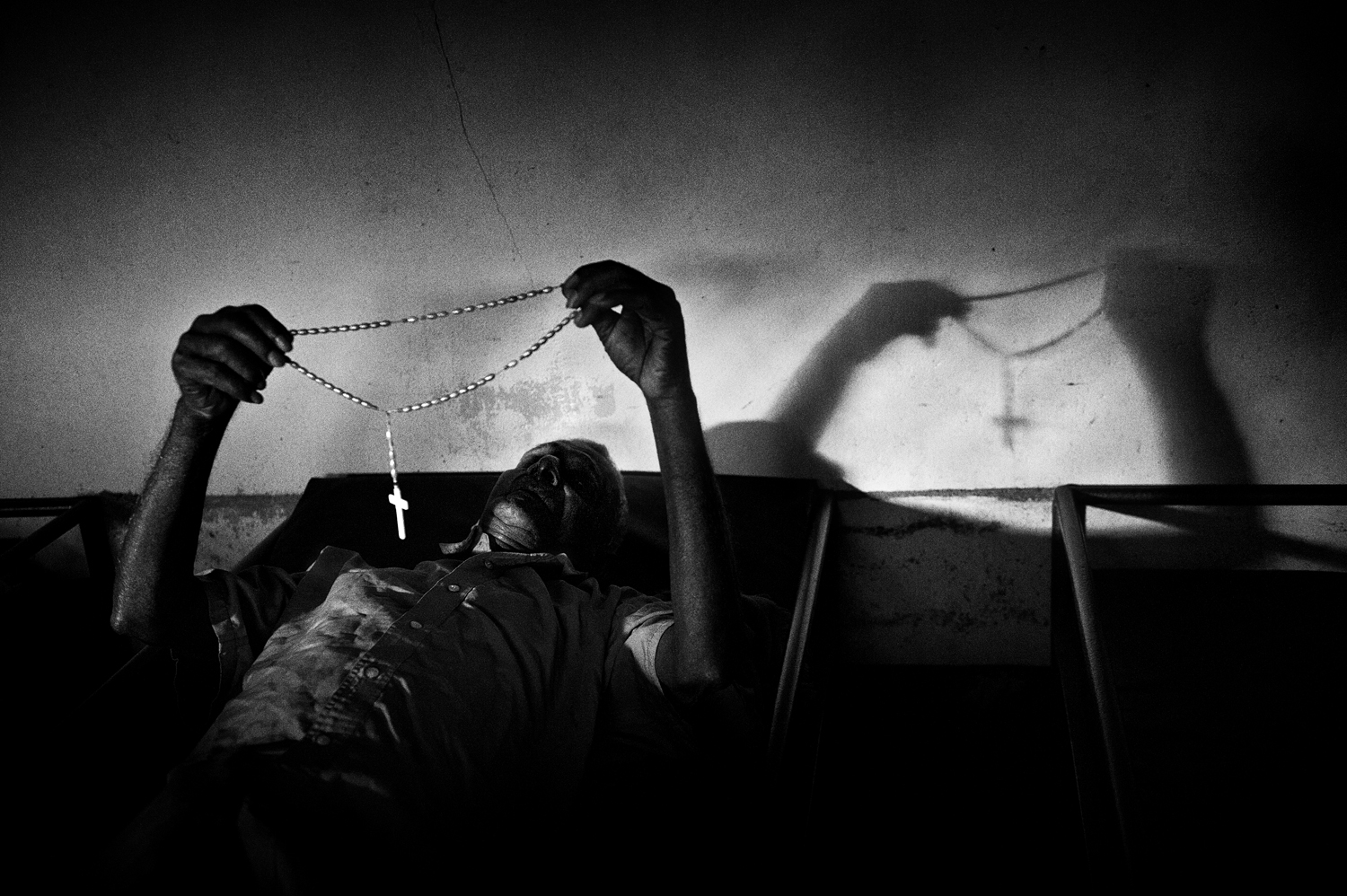

Marchetti, who had previously documented incarcerated youth in Nicaragua, describes the facilities where the abandoned are held captive, hidden from view, “exactly like a prison.” These places are improvised, overcrowded, unsanitary and inadequate. Far from any kind of serious rehabilitation, the majority volunteer-run NGOs offer little more than some food—when they have it—and a place to sleep.

“Most of the money,” he adds, “comes from the church, so there is a condition that you have to respect if you want help.” This means following Catholic teachings and praying several times daily, starting at dawn, even though over half of Kerala’s native population practices Hinduism, and a quarter are Muslim.

To document the scope of the problems, Marchetti adopted a fly-on-the-wall approach, staying silent and as invisible as possible, attempting to forget his own cultural background and immerse himself in the environment. He’d spend hours each day in a facility observing, and when possible, spending the night, if only “to breathe the sensation.”

“If you want to take a good picture, it’s not only a technical gesture, it’s something about you,” he says. “You need to listen, you need to understand, to spend time and spend yourself, your emotions.”

The most vivid thing that he remembers from his experience was a personal connection he made in a mental hospital. “I was taking pictures of someone who seemed perfectly normal—normal like me.” And though he knew little of the local language and could not speak with his subjects, Marchetti notes that “it is incredible how I could easily communicate with my eyes. Respect is a universal language and you can convey it without words.”

That respect not only gained him access, it also elevated his imagery. His intent, he says, was not to make art of other people’s misery, but to come away with an honest and useful report that can generate questions, especially about reforms on the government level.

There’s a delicate balance in that sort of mission, however, and a visually stunning image that grabs your attention, he says, “is the best that I can give back to these people, even if you have to wait for that picture for three minutes, three hours, three days, three months… It is really hard sometimes, but it’s the minimum price that you can pay.”

Paolo Marchetti is a photographer based in Rome and Rio de Janeiro. In 2012, Marchetti received a Getty Grant for Editorial Photography.

Eugene Reznik is a Brooklyn-based photographer and writer. Follow him on Twitter @eugene_reznik.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com