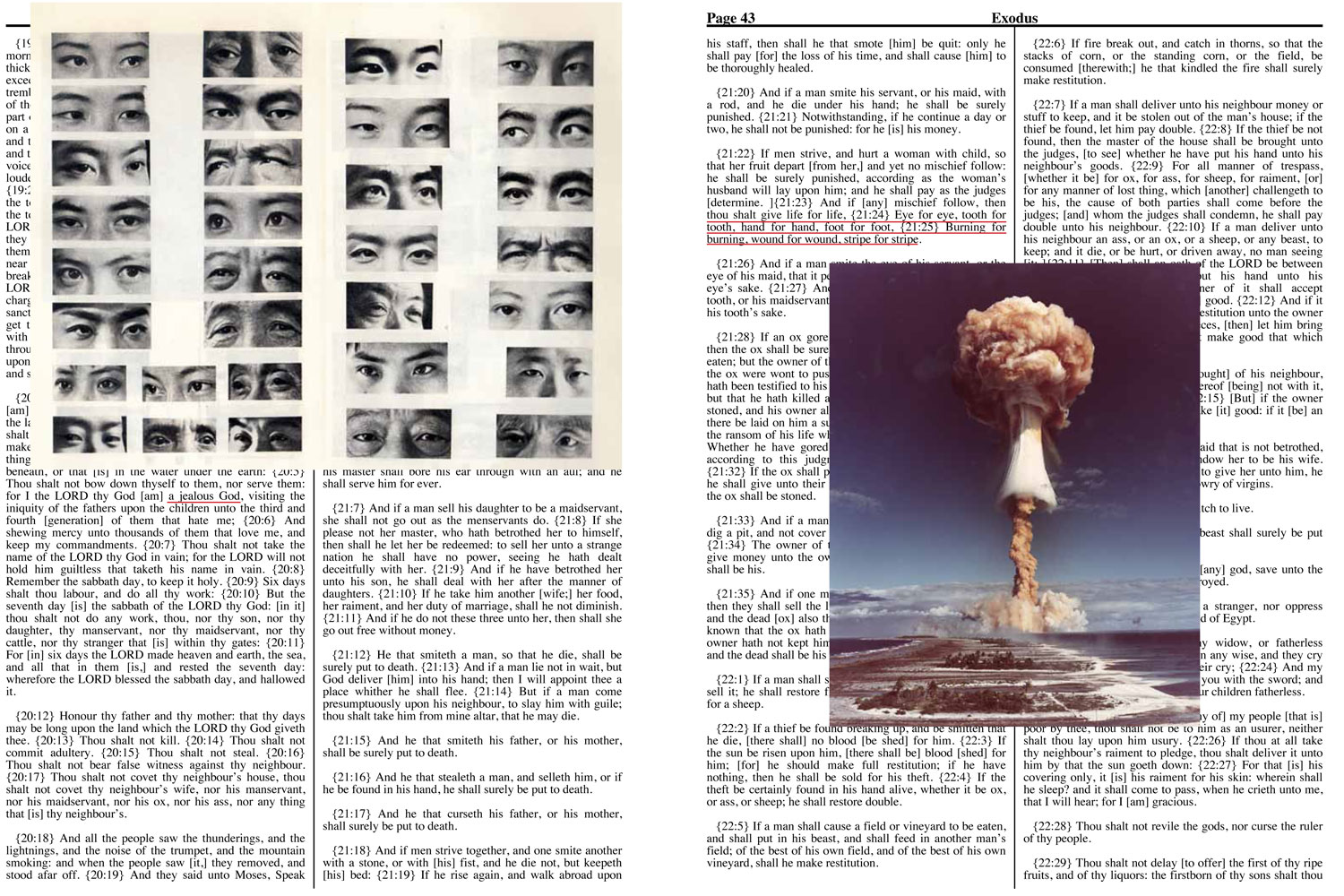

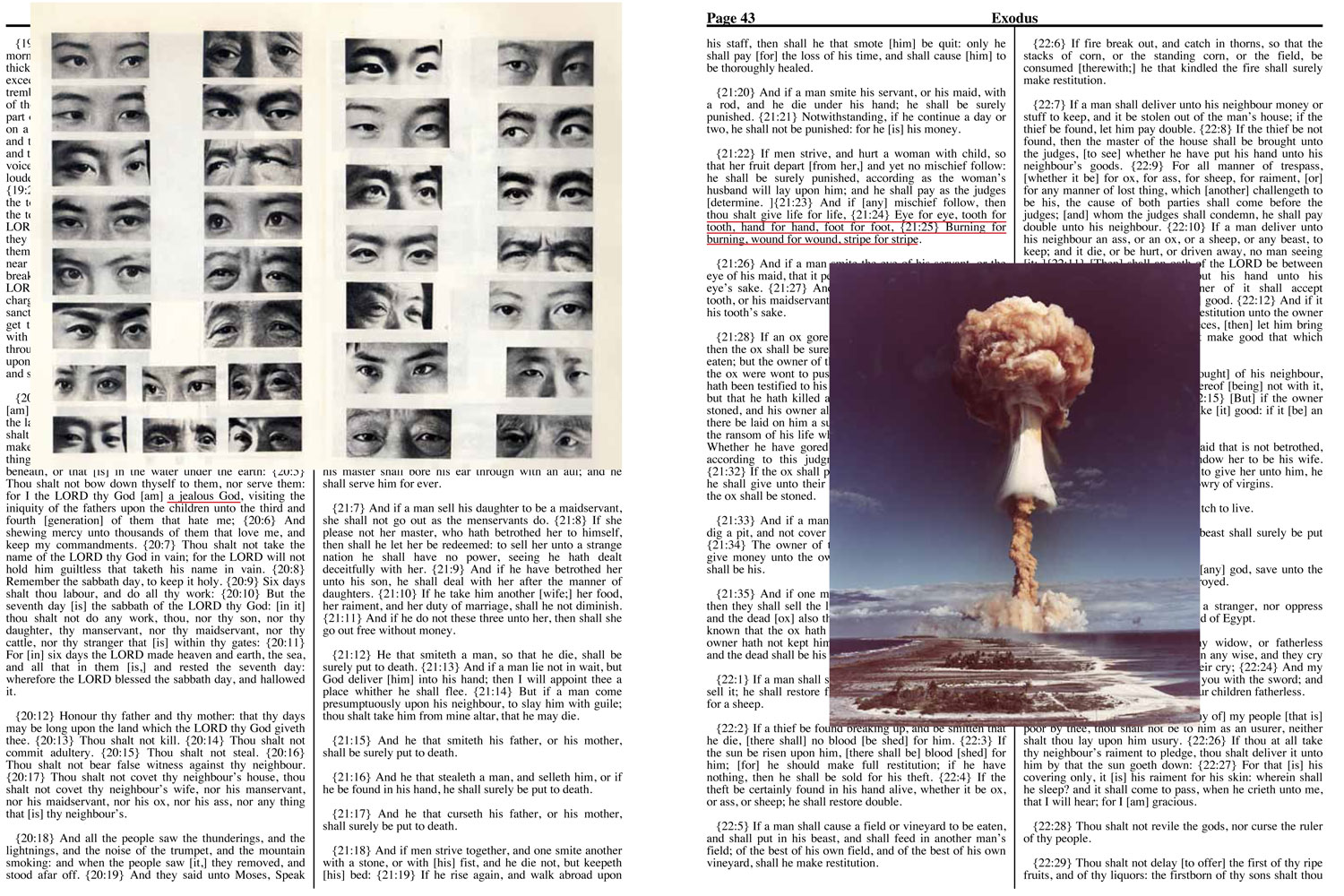

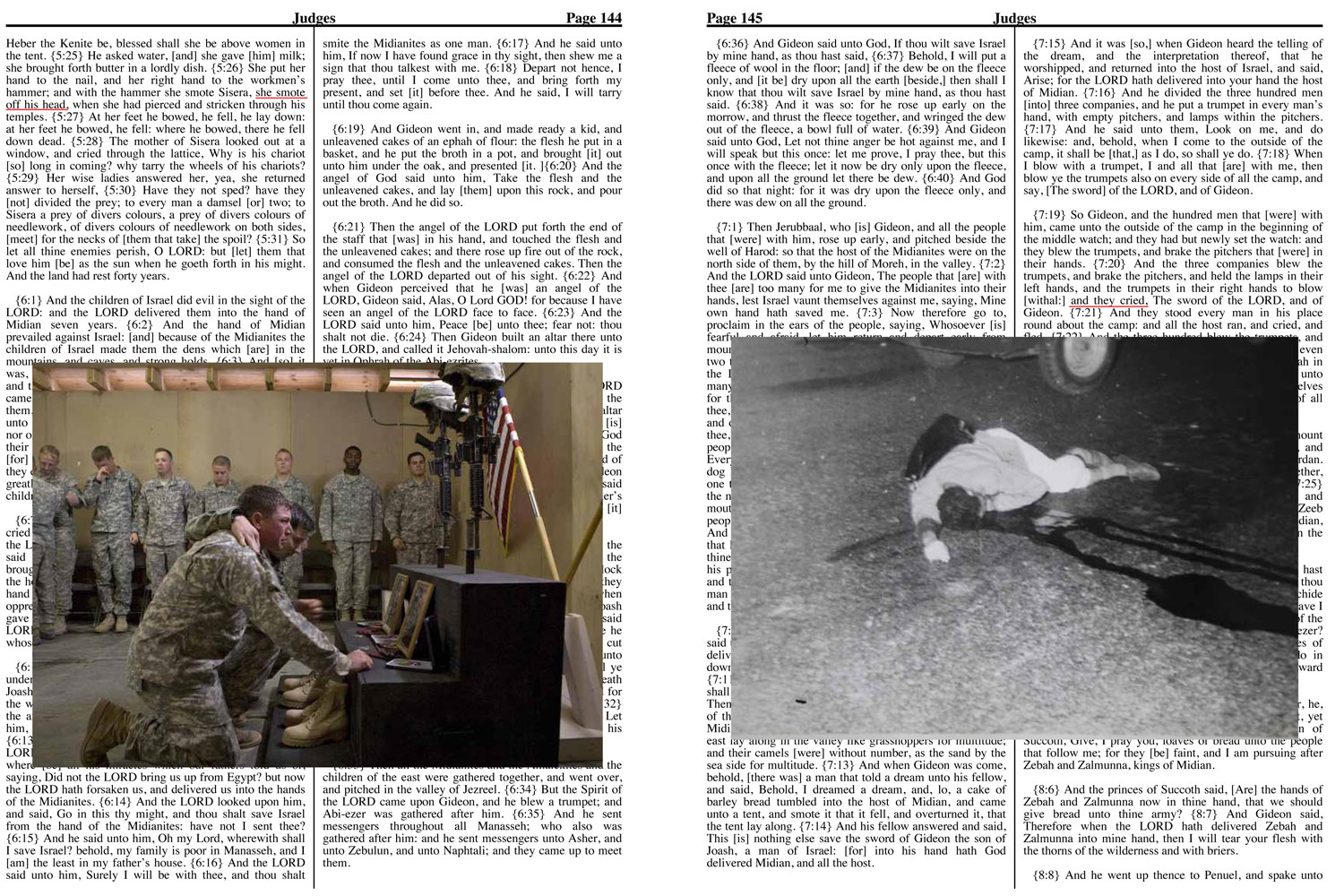

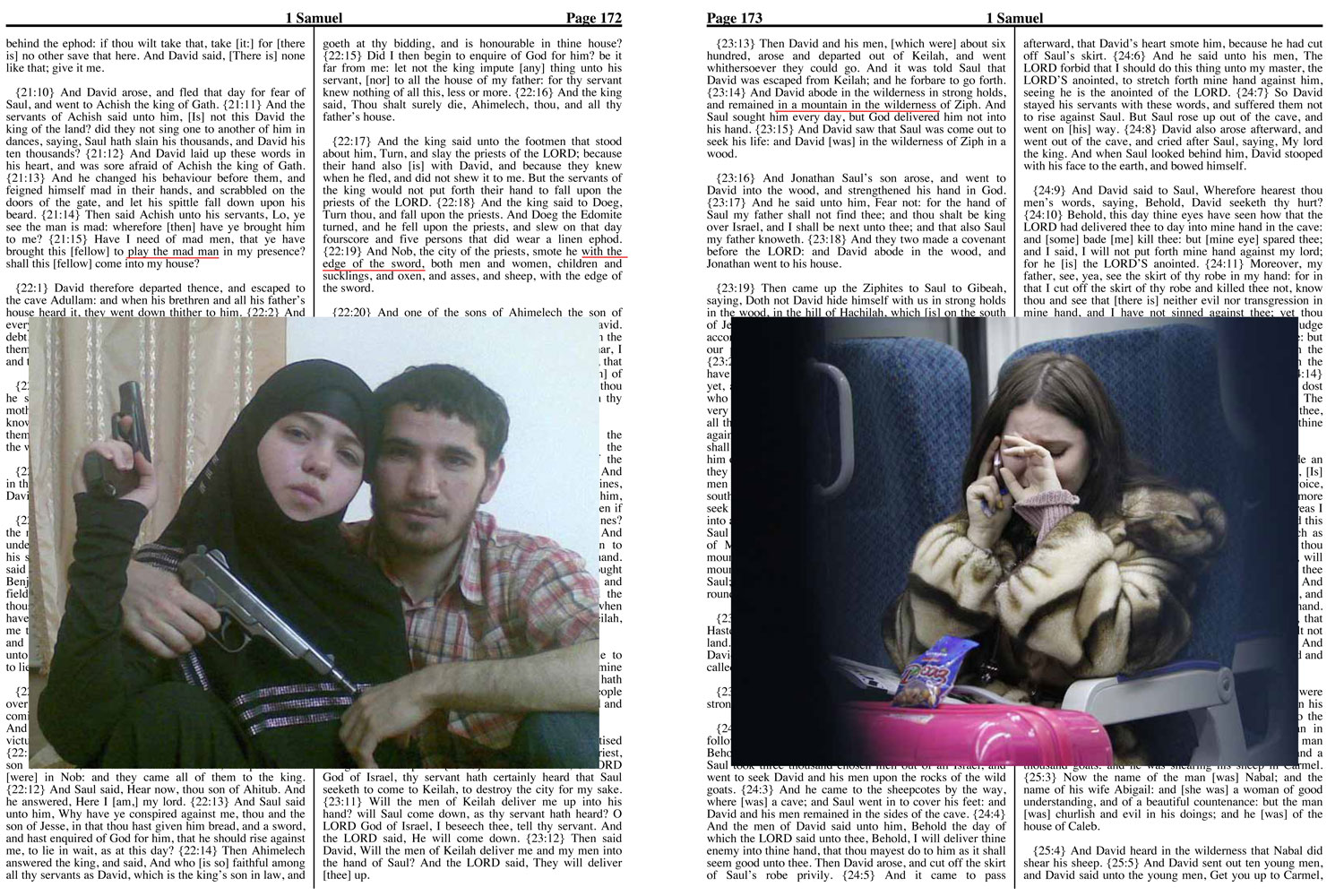

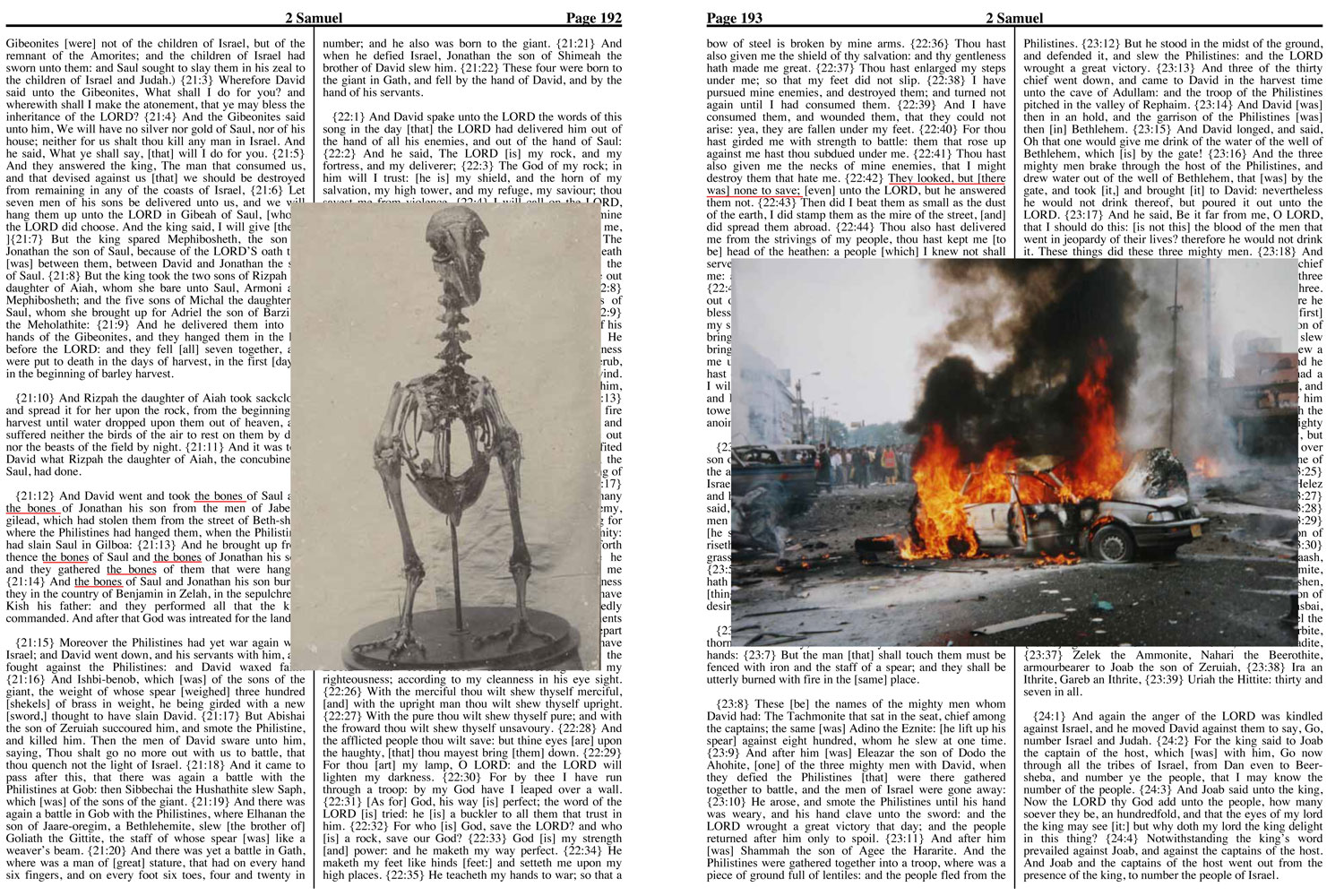

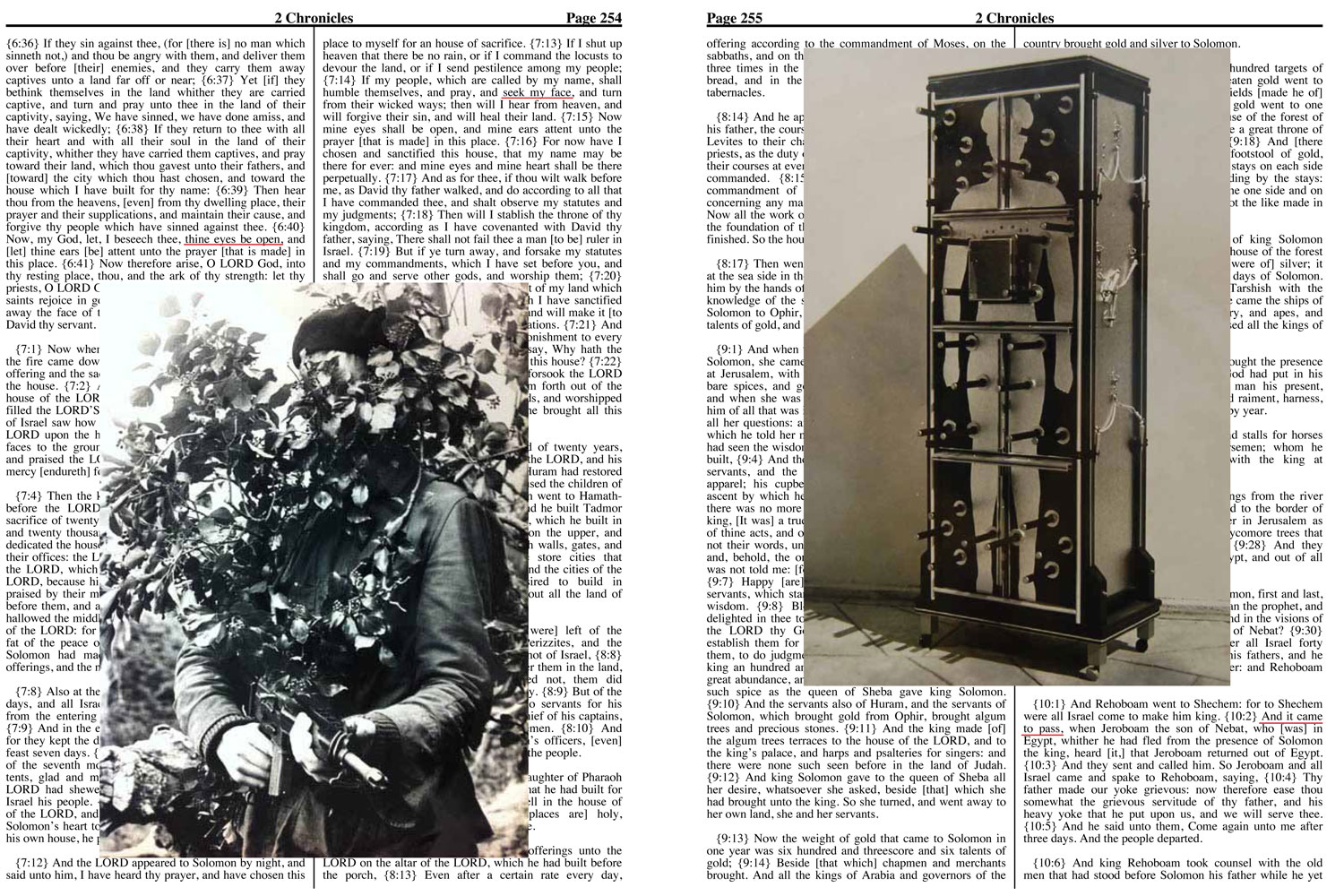

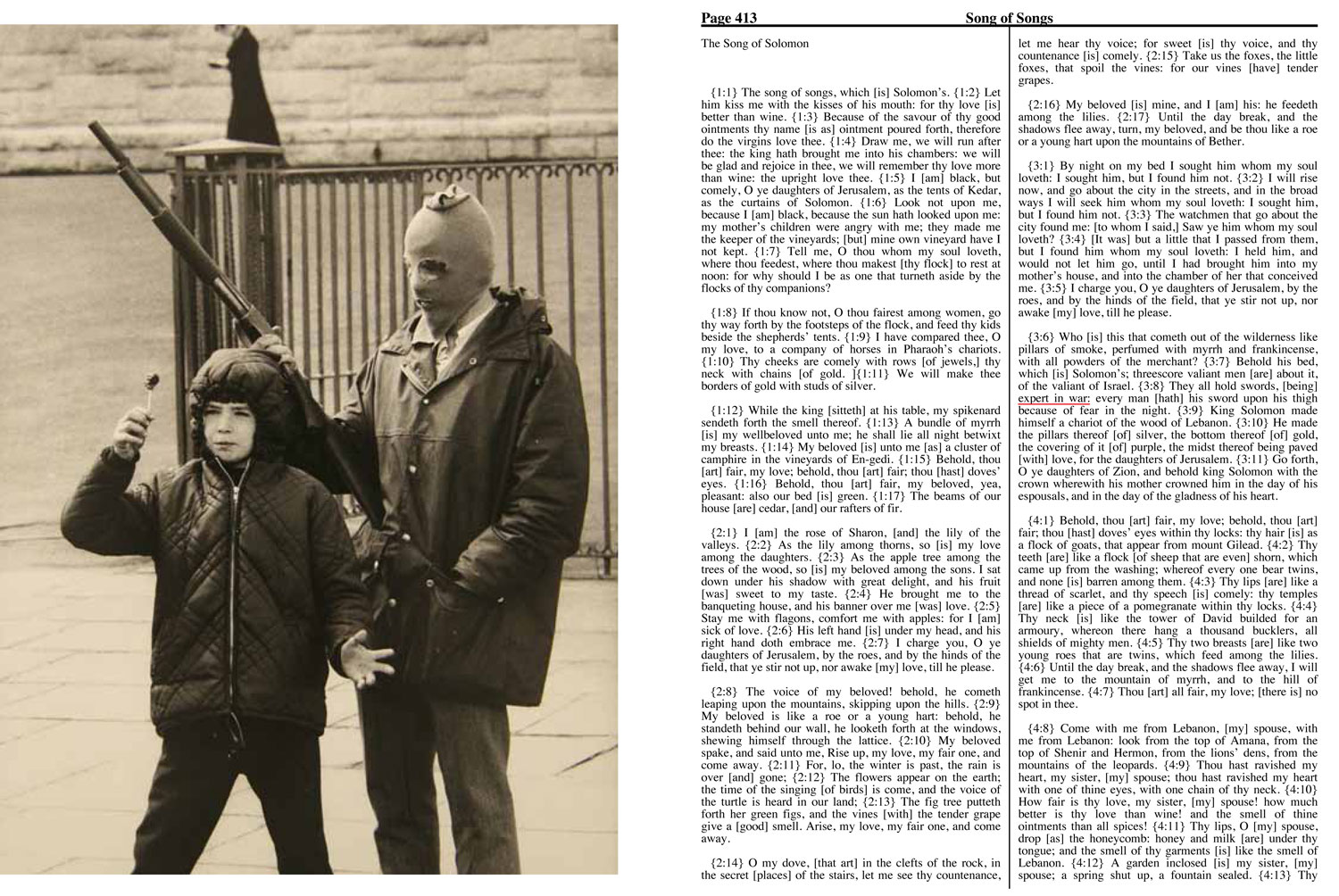

The artistic collaboration between Adam Broomberg and Oliver Chanarin has spanned over two decades since their beginnings working as photographers for Tibor Kalman’s Colors magazine in the early 1990s. Using a wide variety of means, their practice, which has often concerned itself with how history and current events are perceived through images, reevaluates and challenges the classic ideas of photography as a tool for documenting the social condition. Broomberg and Chanarin have authored ten books including Trust (2000), Ghetto (2003), Chicago (2006) and People in Trouble Laughing Pushed to the Ground (2011). Their latest book project Holy Bible is being released this month by MACK.

Jeffrey Ladd: Can you talk a bit about this current book project Holy Bible? Had it evolved from your recent work War Primer 2 which is a modern reinterpretation of Bertolt Brecht’s Kriegsfibel (War Primer) from 1955?

Adam Broomberg & Oliver Chanarin: When we were researching Brecht’s work in Berlin we stumbled across his personal copy of the Holy Bible. It caught our attention because it has a photograph of a racing car glued to the cover. It’s a remarkable thing, and in retrospect, seeing and handling this object definitely planted the seed for this book. Just like the War Primer, our illustrated bible is broadly about photography and it’s preoccupation with catastrophe. Brecht was deeply concern about the use of photographs in newspapers. He was so suspicious of press images that he referred to them as hieroglyphics in need of deciphering or decoding. We share this concern. Images of conflict that are distributed in the mainstream media are even less able to affect any real political action now then they ever were.

An essay by Adi Ophir called Divine Violence is reproduced in an epilogue to Holy Bible. How did you come to this particular essay?

If you read the Old Testament from cover to cover, you notice very quickly that God reveals himself through acts of catastrophe, through violence. Awful things keep happening: a flood that just about wipes out most of his creation, the destruction of Sodom and Gomorra – we constantly witness death on an epic scale and the victims hardly ever know what they have done to deserve such retribution. Adi reflects on this theme of catastrophe in a really interesting way that connects with our modern lives. He concludes:

“States that tend to imitate God benefit from disasters… even when they cannot claim to be their authors, because any such disaster may serve as a pretext for declaring a state of emergency, thus reclaiming and reproducing the state’s total authority. And when earthly powers imagine that they can take His place in the divine economy of violence, faith may provide resistance but no shelter. It is not God’s response to human sins but sheer human hubris that might bring the world to its end.”

This extract from his book, Two Essays on God and Disaster, became a philosophical and political map for the whole project. We felt lucky that he permitted us to publish it, as it’s previously only appeared in Hebrew. We’re going to badly paraphrase his argument, but Ophir suggests that the Old Testament is essentially a parable for the growth of modern governance (God eventually chooses his people, issues them with a set of commandments and punishes them when those are broken). At the same time, he points out that when his laws are broken, he meters out the most radical, unimaginably violent punishments. So this reading of the Bible suggests a contract we are all silently and forcibly bound into with the modern state and our naïve acceptance of the harsh punishments the state meters out; prison, the death sentence, a war on drugs, on terror… The camera has always been drawn to these themes, to sites of human suffering. Since it’s inception it has been used to record and also participate in catastrophic events. Catastrophe and crisis are the daily bread of news.

Is it possible any longer in your opinion to provide images directly with a camera from war or natural catastrophes that are not in some way undermined by this?

We both believe that events still need to be witnessed and documented. But what happens when those images of suffering are turned into currency, into entertainment/ Recently we were asked to give a presentation of our book, War Primer 2, which contains some of the infamous Abu Ghraib torture images. We had a moment of concern regarding the copyright of these images and did some research into the reproduction rights. It shocked us to discover that most of these well-known torture images are syndicated by the Associated Press. When we approached AP before we gave a public lecture showing the material, they requested that we pay £100 per image per presentation. How is it possible that those images have become currency? We must owe them hundreds of thousands of dollars by now.

Photographs are essentially mute in telling the “who, what, why, when, where of journalism without a caption and where simple gestures are read, properly or not, as a kind of photographic “shorthand” – what responsibilities do you feel a contemporary journalist with a camera has in bringing images to the public?

Is there still such a thing as a contemporary journalist with a camera? Anybody with a telephone could pass for one. And the world, particularly war zones, are littered with cameras. Soldiers, insurgents, civilians, even weapons — all have cameras attached to them. The so-called professional journalist must contend with all these other forms of witness. We have engaged with so-called war zones and skirted around the parameters of violence. But we’re cowards and have always kept back from any real prolonged danger. The Tim Hetherington’s and Chris Hondros’s of this world are a different breed. Our role, is to instead think about how images produced in the theater of human suffering are consumed; the individual response to such images. We only went to conflict zones to explore these ideas, never to responsibly document any specific war.

How did you come to decide to use the Archive of Modern Conflict for gathering images as opposed to using many sources? Was there a method you applied to sifting through AMC since it contains vast amounts of material? How did you approach such a task?

The Archive of Modern Conflict is a weird place — a lot of that comes through in our book. Officially it’s an archive that spans the history of the medium and concentrates on images of conflict. Looking through the thousands of images at the AMC, the narrative that unfolds is not at all a straightforward account of war. It’s an extremely personal and very idiosyncratic one; an unofficial version of the history of war.

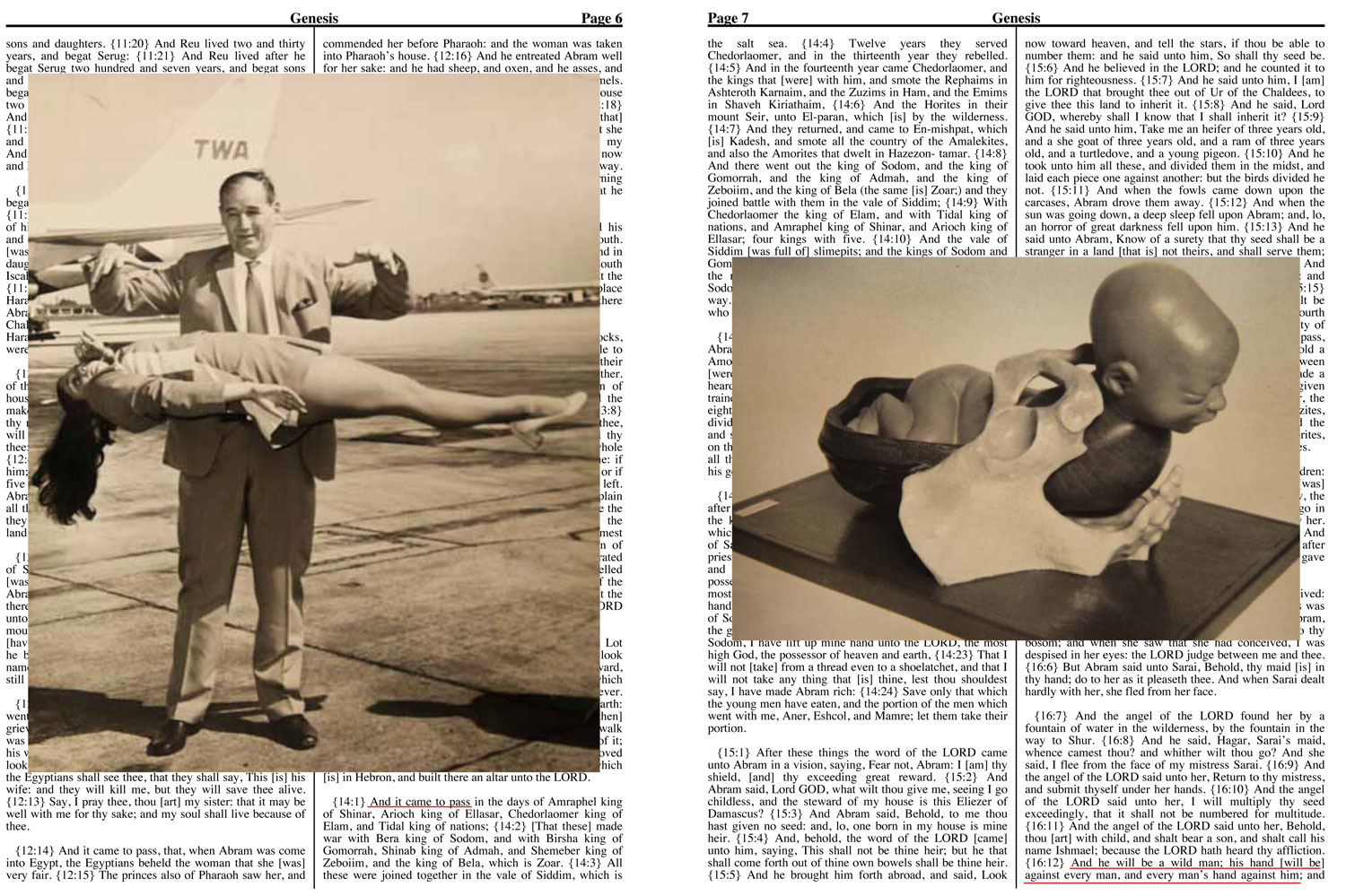

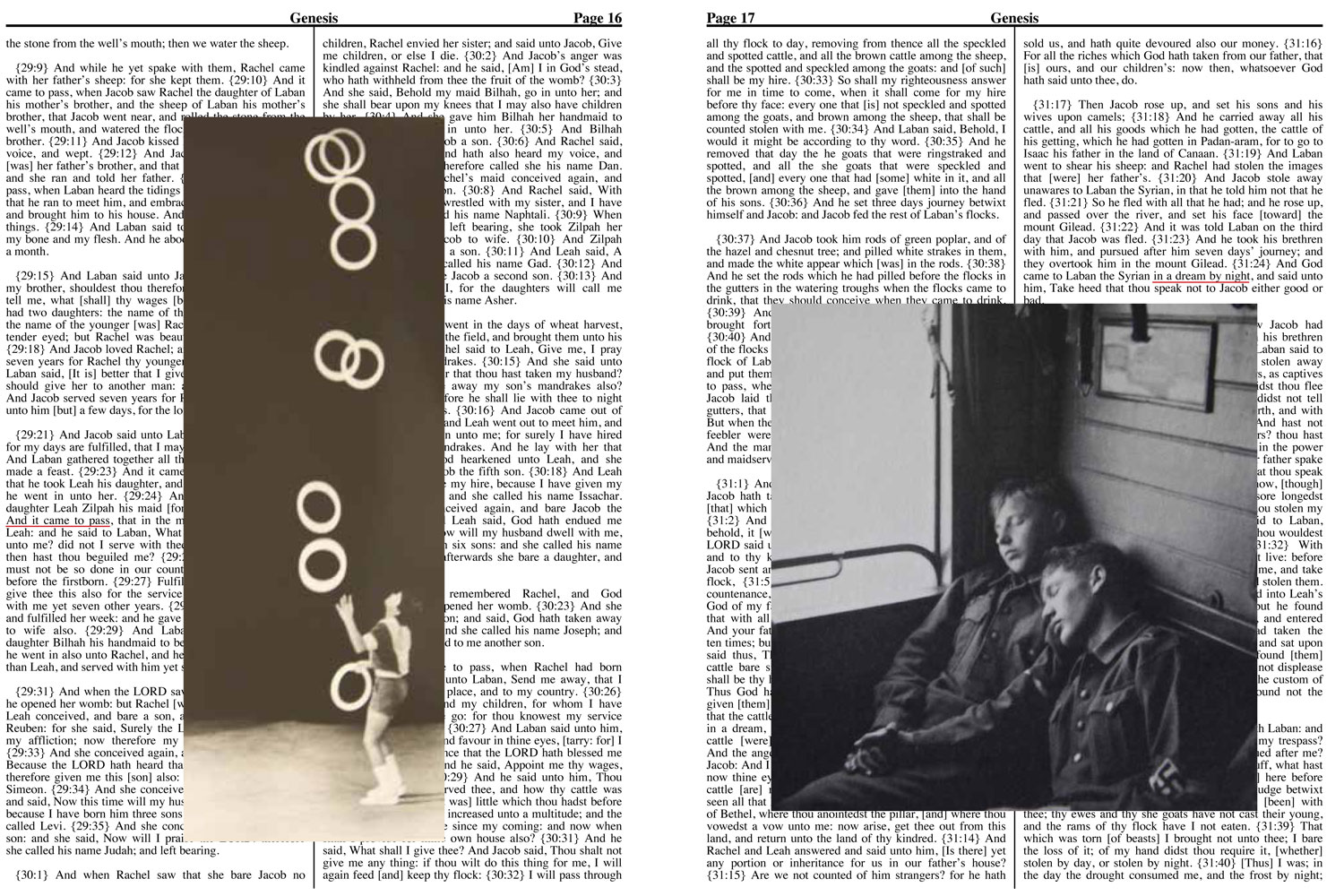

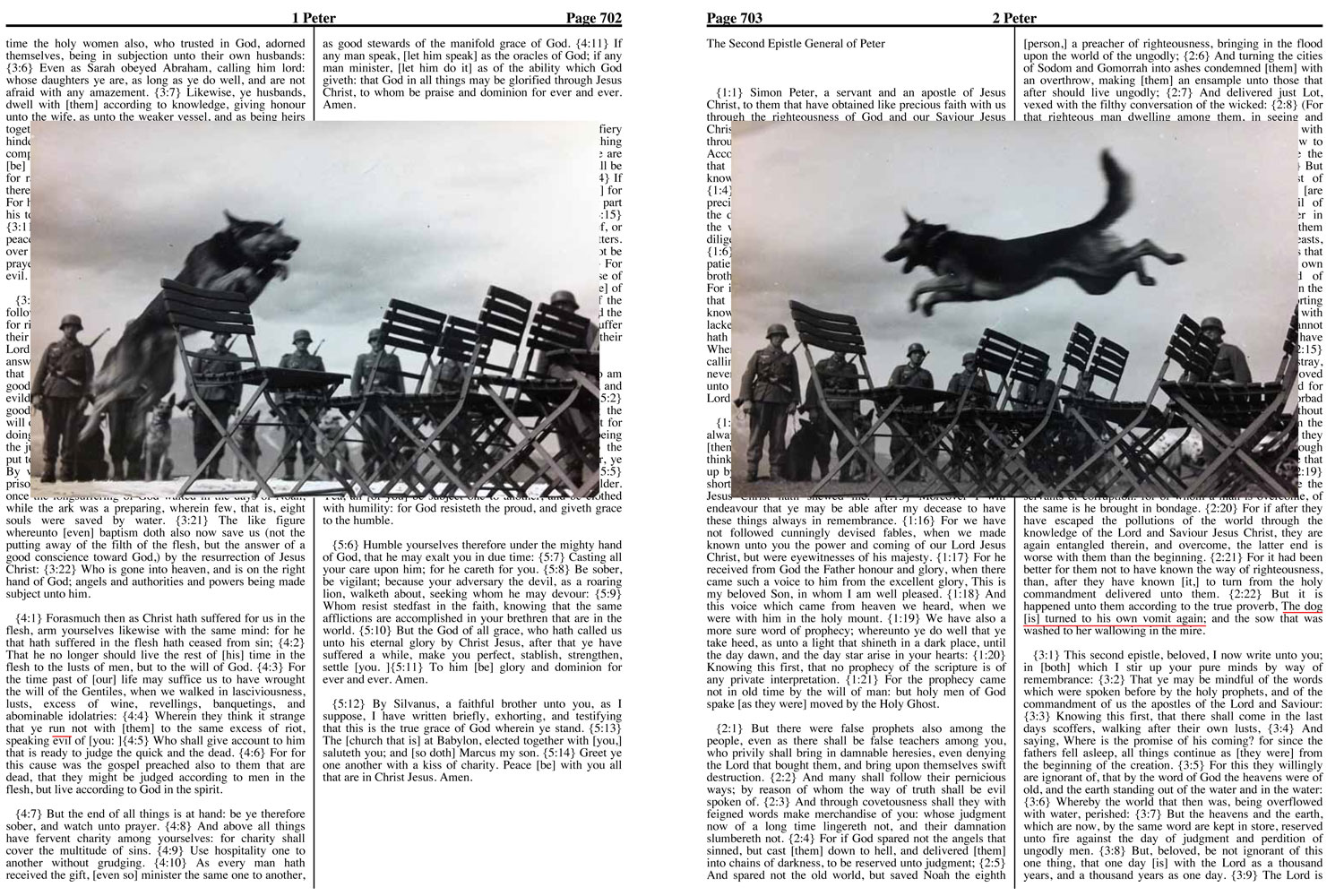

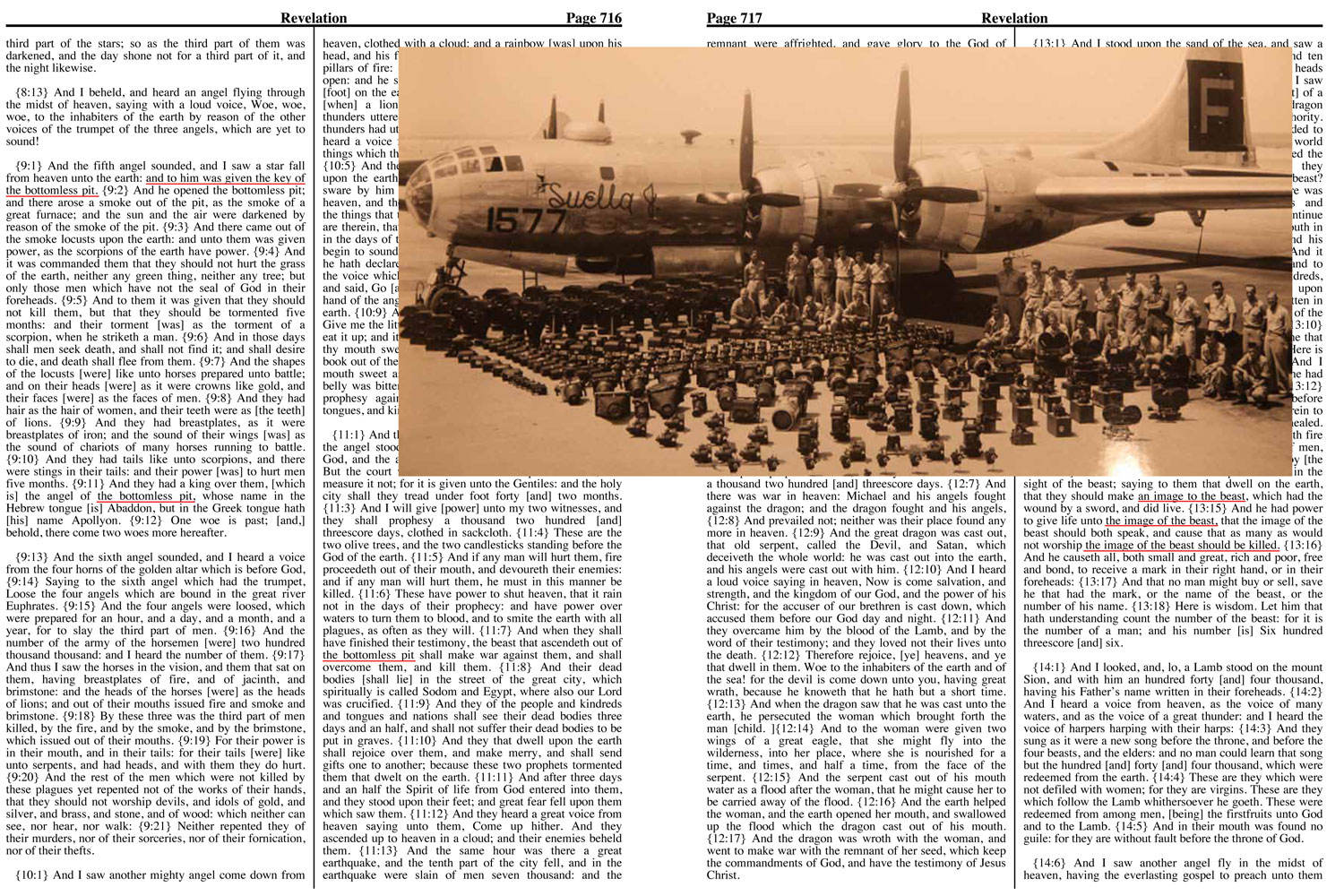

One shelf contains hundreds of personal albums of Nazi soldiers. We see moments of intimacy between men — we see them kissing their wives goodbye, hugging their children and then fooling around with their friends. These images run counter to the narrative we can morally cope with. We’re not used to seeing Nazi’s displaying human traits; showing tenderness, emotion, desire. Our days at the archive sifting through all this material was difficult. So many dead people. It’s depressing. But somehow we discovered a lot of humor, too. In particular, a large collection of photographs of magic tricks became a running motif through the book. We always pair these delightful images with the phrase, “And it came to pass,” which appears again and again like a form of punctuation throughout the text.

Words as image (I am thinking of work on the Egyptian surrealists), or texts integrated into the images, have played a part in your practice. In this work had the underlined fragments found on the bible pages come first and then the images paired?

Our only intervention is to underline phrases on each page to add an image. Pick up any old Bible and you might see similar notations. There is a long history of this. But we wanted to avoid a purely illustrative relationship between words and images, so at times the connection is quite oblique. Anybody reading through will be able to make their own connections.

The scope of your practice has extended beyond making images in fairly traditional ways (working as creative directors at Colors magazine) to including appropriated images from archives and exploring different narrative styles. How has this shaped (and evidently challenged) your notions of photography?

We’ve always been more interested in the ecosystem in which photography functions rather then in the species itself; more intrigued by the economic, political, cultural and moral currency an image has then in the medium. We’re fascinated by how images are made but also how they are disseminated, and how that effects the way they are eventually read. Photographs are the most capricious objects — way less faithful then words. They can’t be trusted. So we need to be on guard just looking at them, never mind making them. We still take photographs, however. It’s just that we don’t radically discriminate between images we take and those that we find. We’re equally mistrusting of both.

As collaborators, you have worked both in books and exhibitions in a certain degree of success where many of your projects work well in both forms. You have also started your own small imprint Chopped Liver Press. I was wondering if you have a preference for the intimacy of books over the public exhibitions?

The definition of ‘book’ is undergoing a radical transformation. Far from becoming obsolete, the book — particularly the photo book — is experiencing a new lease of life. They speak to us. They turn their own pages. They update themselves. They have been de-materialized. Chopped Liver Press emerged as a response to this. We make handmade books in our studio. Very limited runs. When they are gone, that’s it. For War Primer 2, however, we produced two versions, a handmade edition of just 100 copies that was instantly sold out, and an e-book version that was freely available and continues to be downloaded. The code that powers these digital books is limited. But there’s great potential for intimacy.

I understand you are both artists and your role is bringing thoughtful art and ideas to the table and where it leads after is not really your business. But, is there any frustration in the thought that these ideas or philosophies get trapped by the “art world” in which they are presented and the world of philosophy (another comparatively small arena)?

We are more interested in the world than the art world, which is exactly why we are so honored to have this conversation with you.

Holy Bible is being published by MACK in June 2013.

Jeffrey Ladd is a photographer, writer, editor and founder of Errata Editions.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com