Photographic technology was born in Europe, but the art of photography as we know it, was invented in the USA during the 1950s and 60s, sponsored by the Museum of Modern Art in New York. John Szarkowski, MoMA’s powerful Director of Photography, declared that great British photographers belonged to a “documentary tradition” that included Bill Brandt (whose press pictures of Britain in the 1930s were exhibited at MoMA in 1969). David Moore’s work from 1987-88, which was first published in Creative Camera in 1988, and now published as a book, Pictures from the Real World, conforms to the expectation that British photographers should, like Brandt, be primarily social observers.

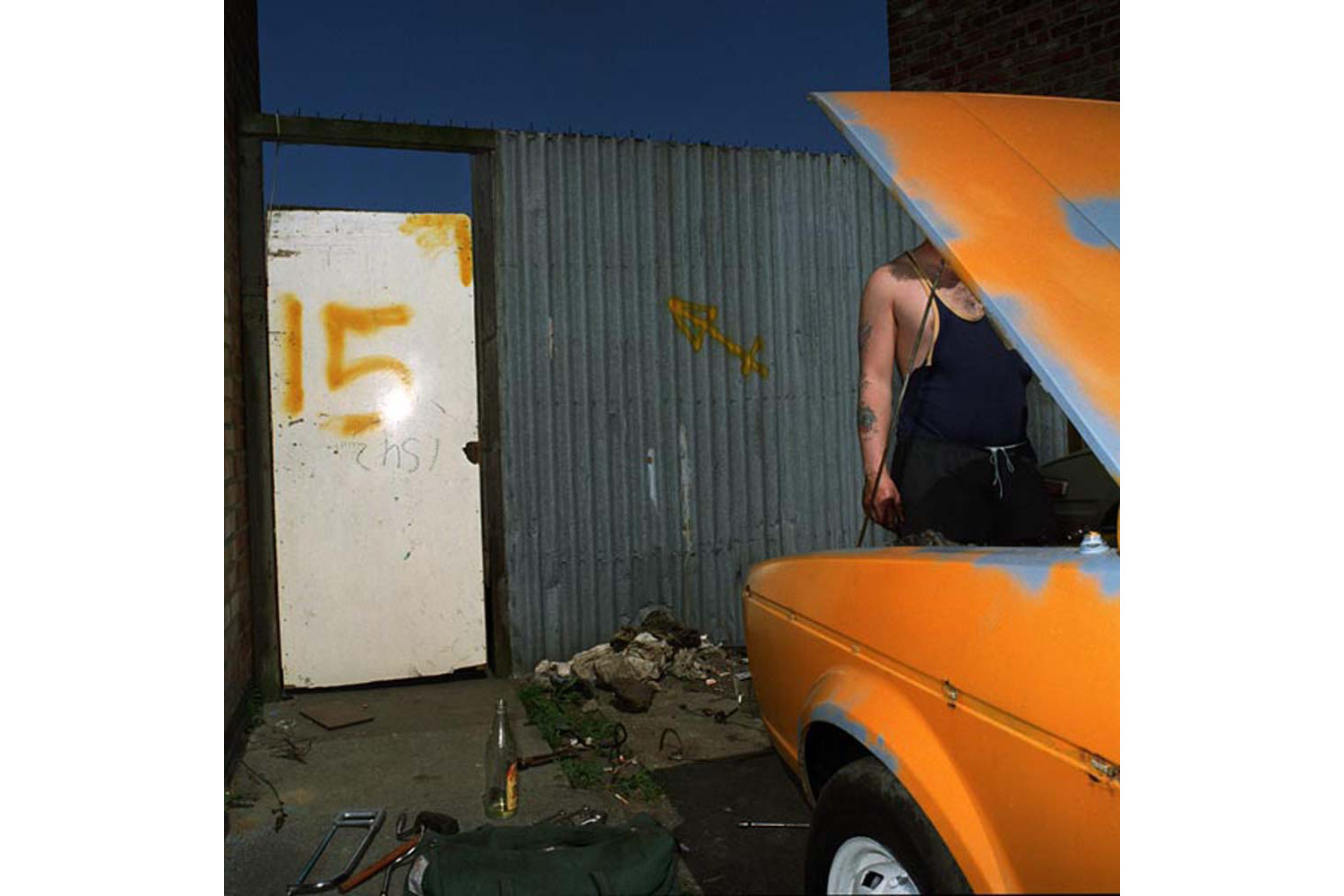

The notion of a “documentary tradition” does not stand up to scrutiny, however, because of the many disparities between Brandt’s generation and Moore’s. Unlike his forebears, Moore benefited from a cultural climate that recognized and rewarded his artistry (the state-funded Arts Council supported dedicated galleries and magazines). This made it possible for him to cultivate a personal style that did not yet conform to the demands of the mass media. Commentators of the 80s interpreted the rather shocking use of color photography, by Moore and others, as a rebellion against the old black-and-white school, but in fact color became simply an extension of a “documentary aesthetic” popularized by the American formalist, William Eggleston.

While Moore was at college (he studied with Martin Parr from 1985 to 1988 at the West Surrey College of Art) the first serious challenge arrived to those who championed documentary photography as both an art form and a tool for reform. In the US and Britain, the theories of French thinkers such as Roland Barthes, challenged claims that photographs were objects of artistic expression or transparent reproductions of “reality.” As these ideas took hold two things happened: the supposed truth of documentary photography became discredited, and it was “saved for art.”

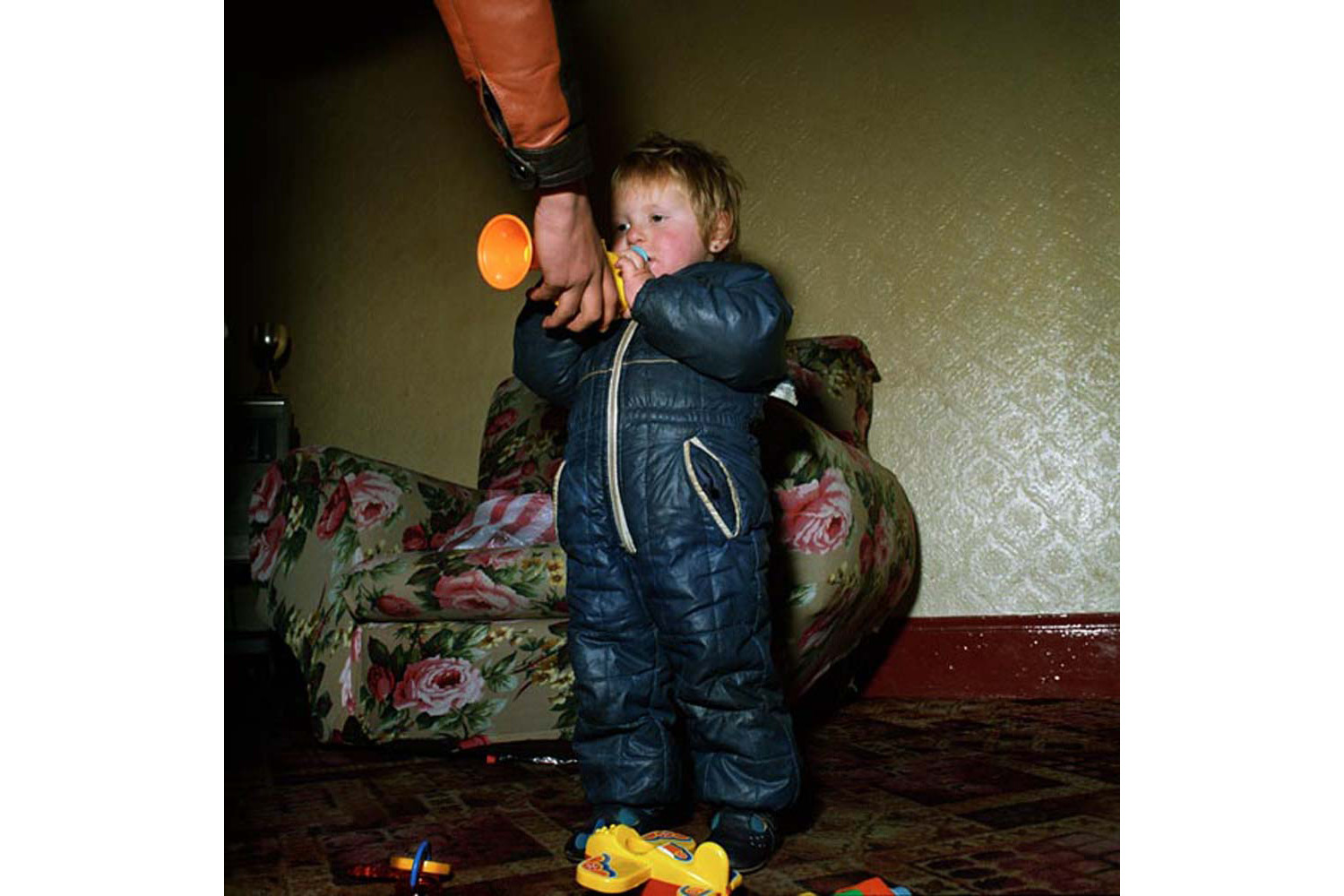

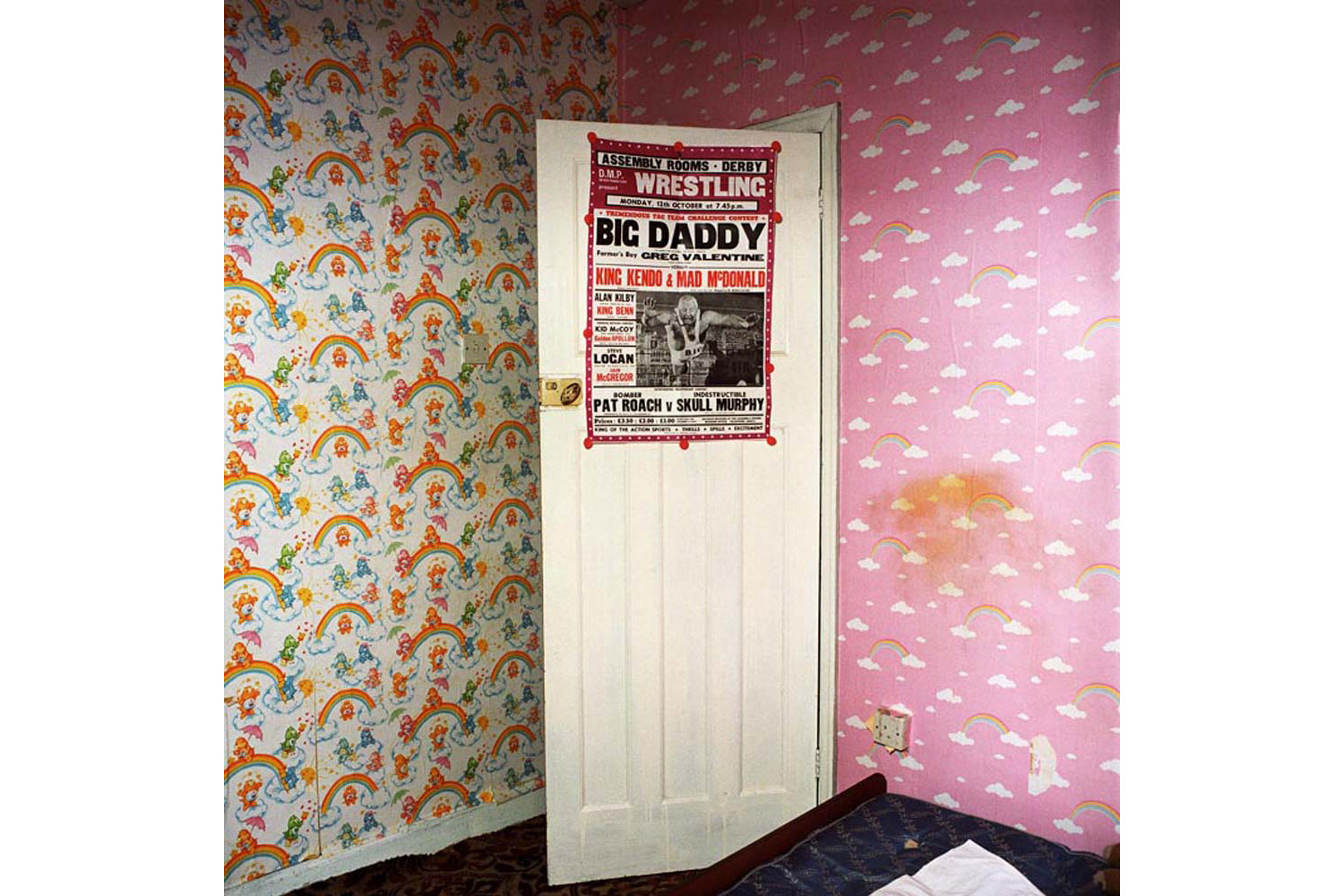

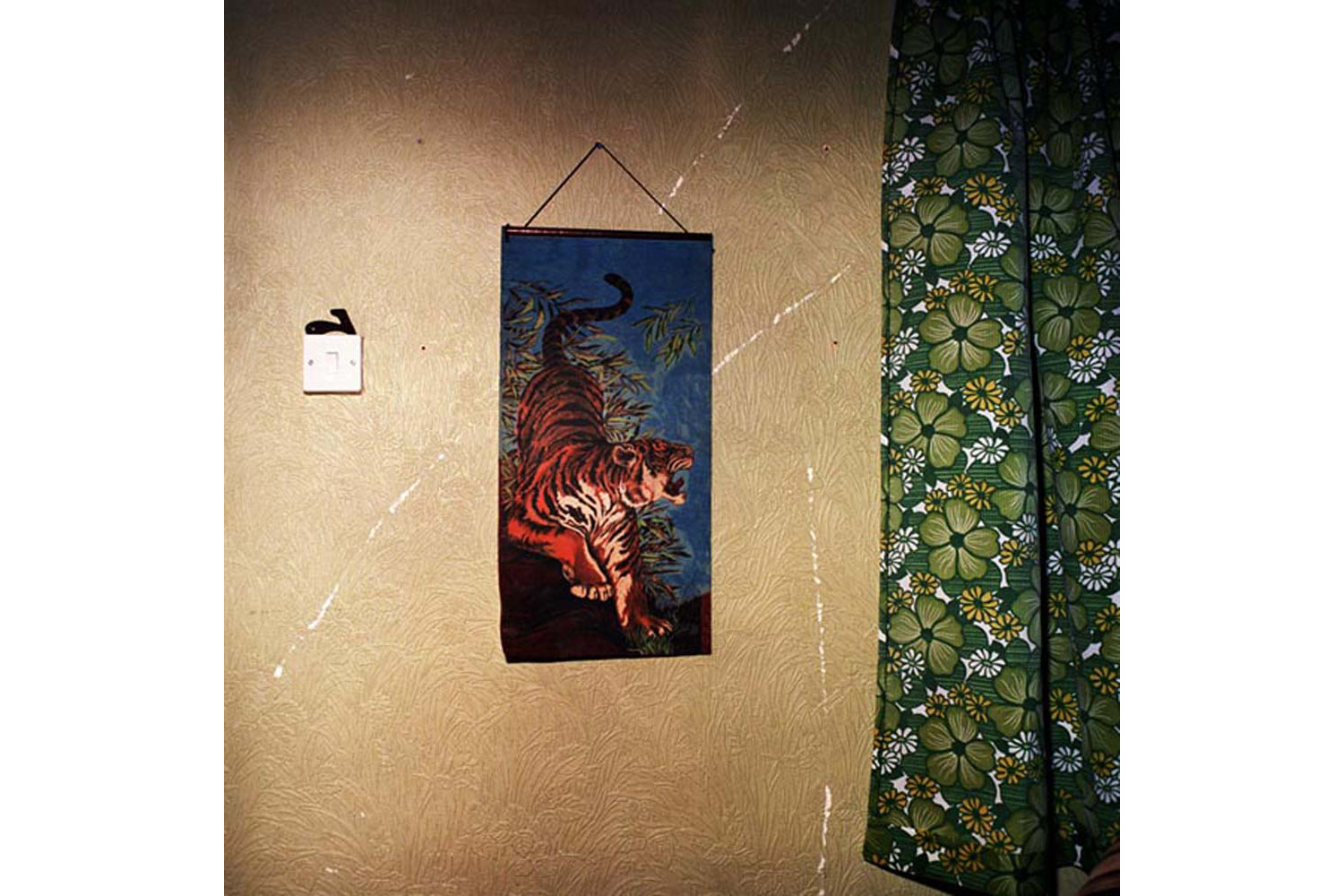

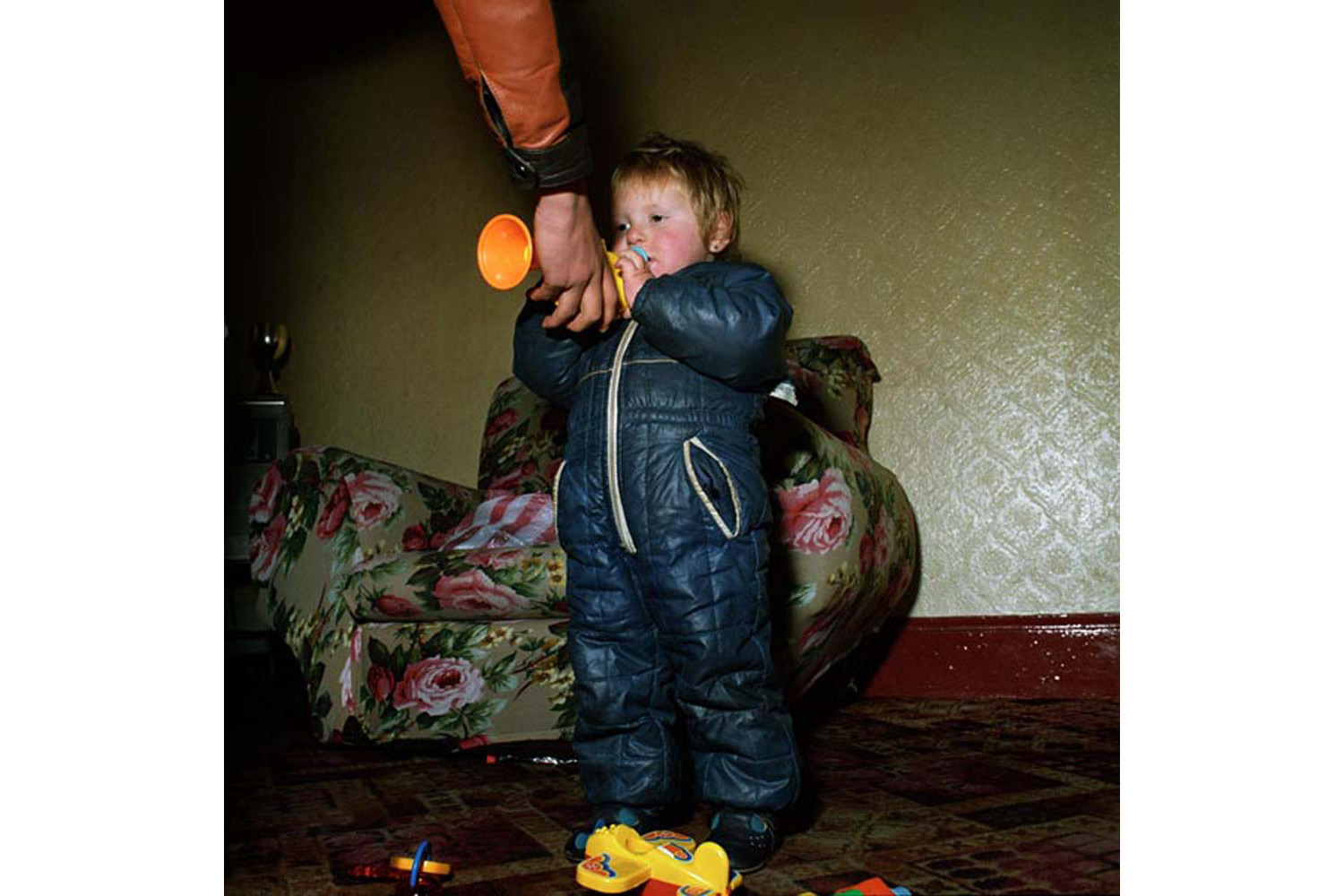

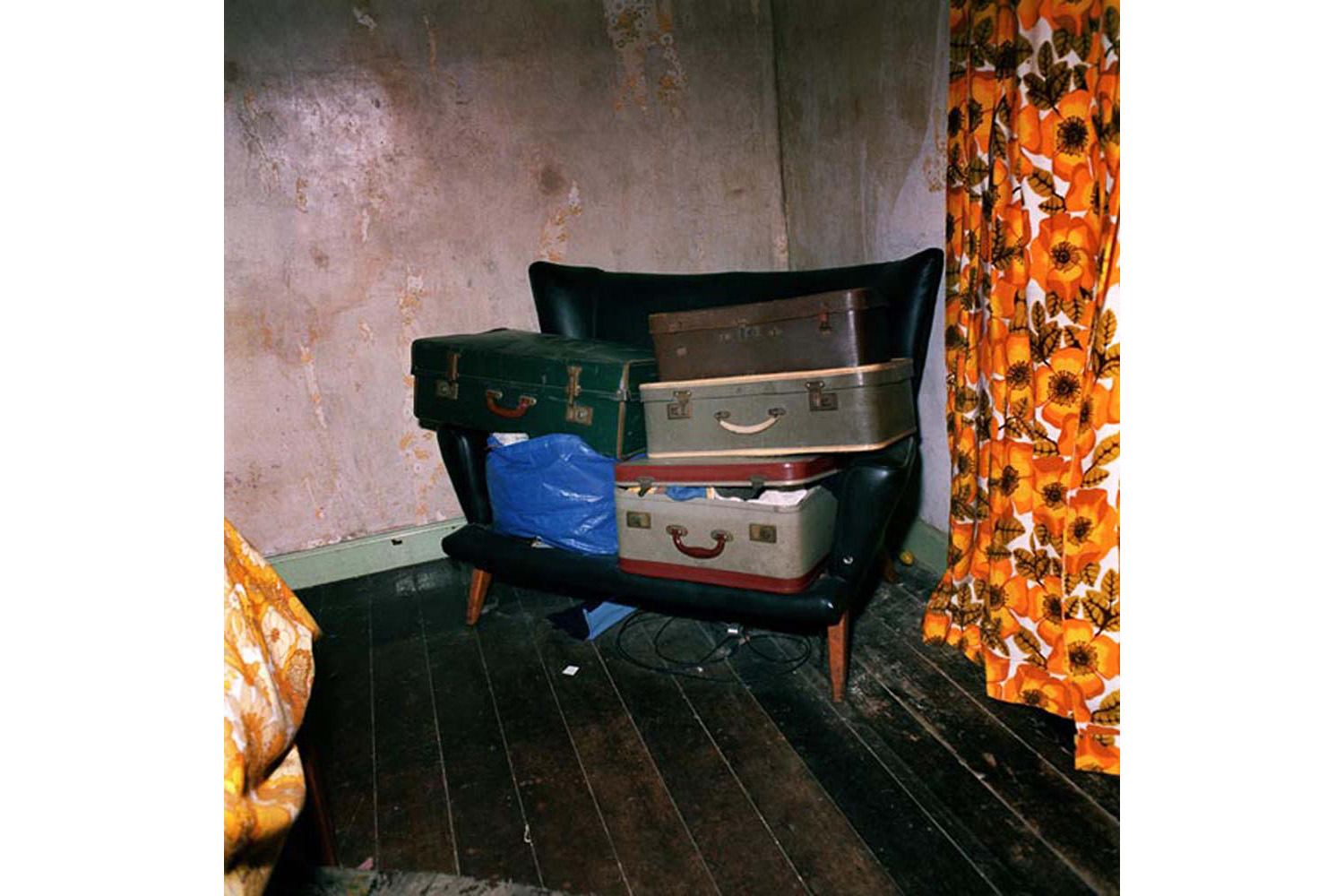

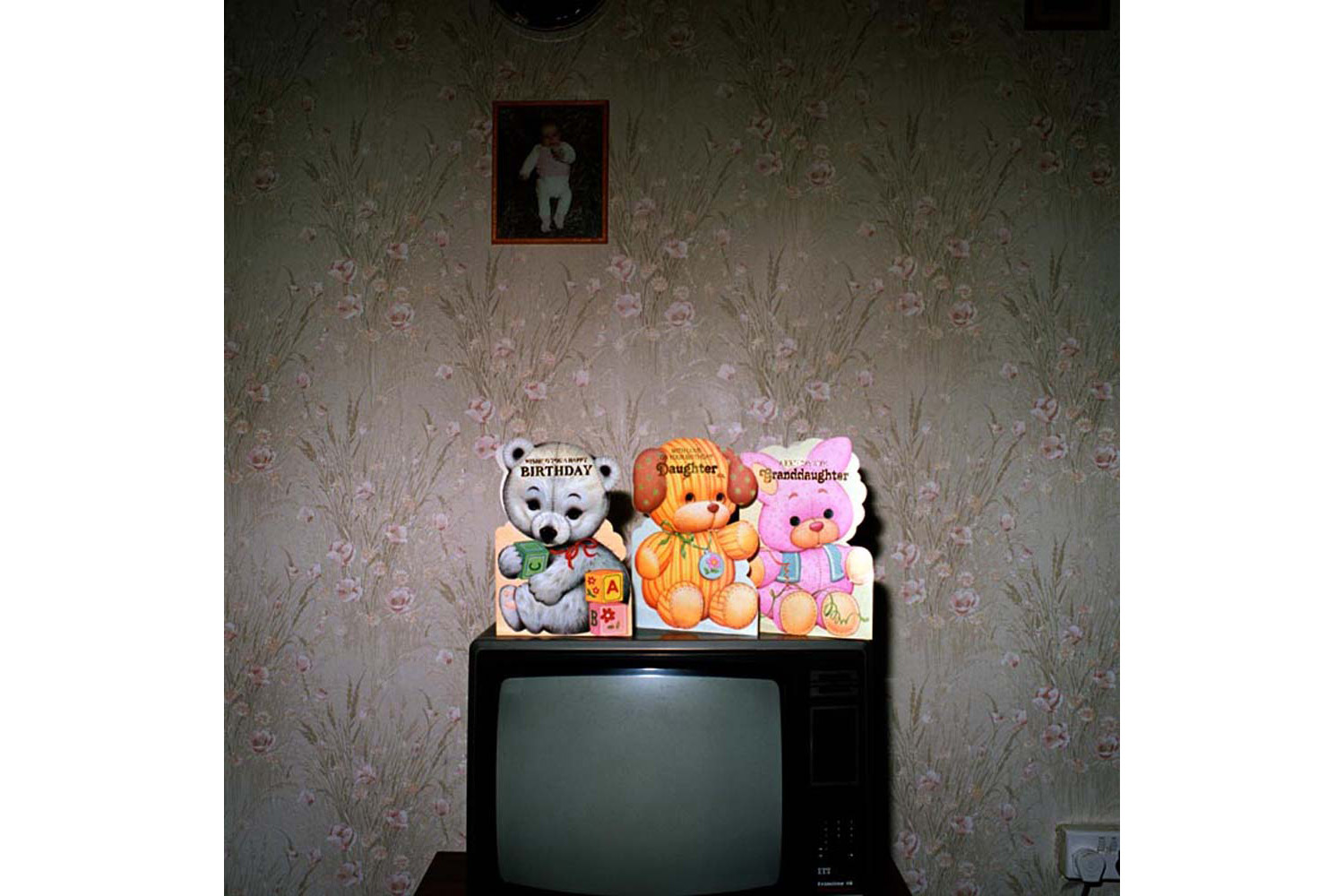

There have been many claims for British documentary photography of the 1980s, including the claim that it was a social critique of the Thatcher years in Britain. This has yet to be demonstrated. Arguably, the most radical aspect of these pictures, is Moore’s refusal of the role of “neutral observer” — something he shares with others of his generation. To eyes accustomed to digitally enhanced photography, many of these pictures will seem familiar. This is because they were cleverly manipulated, both formally (using flash mixed with ambient light to invoke a heightened reality), and conceived, not as “records of life” but opinions. Did Moore just happen to pass by and “snap” the conjunction of the baby and the television image, or did he find the image on a video? Looking back, we can see that this “documentary-style” photography (a term coined by the great American photographer Walker Evans) marked an important stage in the unravelling of the sacred bond between photographer/witness and “reality” that forms the basis of the authority of photography in the press and in society. The relatively recent invention of Photoshop has taken the process much farther.

This is a welcome and important book that is part of a current reappraisal of the British photography of the 1970s and 80s.

Pictures From The Real World (2013) by David Moore is published by Here Press and Dewi Lewis Publishing.

David Moore is a London based photographer who has exhibited and published internationally. He has been working as a photographer and educator since graduating from West Surrey College of Art and Design, Farnham, in 1988.

David Brittain is a curator, critic, documentary maker, lecturer and was editor of the respected international magazine, Creative Camera, (1991-2001). In 2000, his anthology of writings, Creative Camera: Thirty Years of Writing, was published by Manchester University Press.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How Donald Trump Won

- The Best Inventions of 2024

- Why Sleep Is the Key to Living Longer

- Robert Zemeckis Just Wants to Move You

- How to Break 8 Toxic Communication Habits

- Nicola Coughlan Bet on Herself—And Won

- Why Vinegar Is So Good for You

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Contact us at letters@time.com