What do we want from our media revolution? Not just where is it bringing us—but where do we want to go? When the pixels settle, where do we think we should be in relationship to media—as producers, subjects, viewers? Since all media inevitably change us, how do we want to be changed?

There used to be a time when one could show people a photograph and the image would have the weight of evidence—the “camera never lies.” Certainly photography always lied, but as a quotation from appearances it was something viewers counted on to reveal certain truths. The photographer’s role was pivotal, but constricted: for decades the mechanics of the photographic process were generally considered a guarantee of credibility more reliable than the photographer’s own authorship.

But this is no longer the case. The excessive use of photographs to “brand” an image (whether of oneself online, of celebrities, of products, of major companies, or of governments), and to illustrate preconceptions rather than to uncover what is there (presidents are made to look presidential, and poor people are generally depicted as victimized), as well as the extraordinary malleability of the photograph due to software such as Photoshop, make photography more of a rhetorical strategy, like words, rather than an automatic proof of anything. Photographs must now persuade, often in concert with other media, rather than rely on a routine perception that they inevitably record the way things are.

The billion or so people with camera-equipped cellphones, meanwhile, make photography, like all social media, an easily distributed exchange of information and opinions with few effective filters to help determine which are the most relevant and accurate. The professional photojournalist and documentarian, now a tiny minority of those regularly photographing, often are unsure not only how to reach audiences through the media haze, but also how to get their viewers to engage with the often extraordinarily important situations they witness and chronicle.

This moment of enormous transition forces a rethinking of what photography can do, and what we want it to accomplish. For example, if a young person wanted to become a war photographer, we have hundreds of books showing how others have photographed war. But what if a young person wanted, instead, to become a photographer of peace? The genre, unfortunately, does not yet exist.

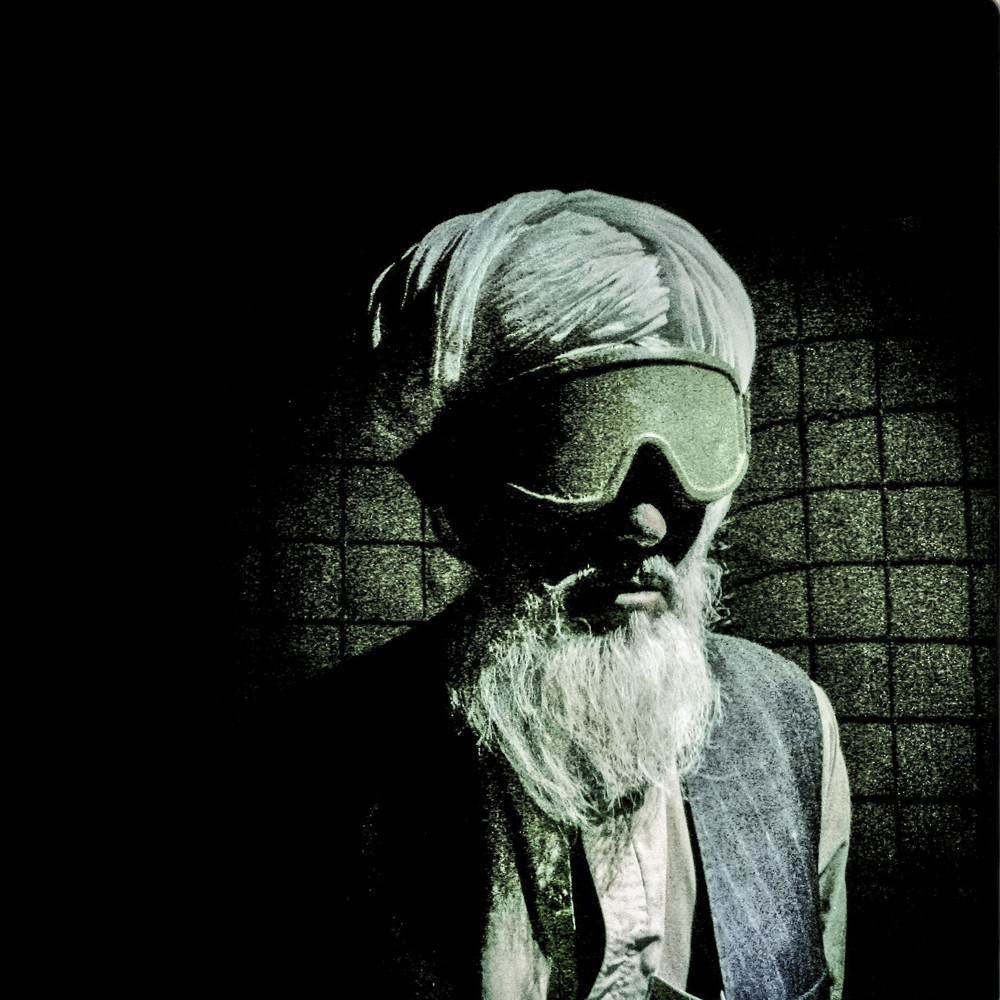

Perhaps, then, we might want to begin focusing less on the spectacle of war and more on those impacted by the consequences of war—as Monica Haller has done, along with many others. The all-type cover of her book, Riley and His Story, disputes any conventional reading: “This is not a book. This is an invitation, a container for unstable images, a model for further action…. Riley was a friend in college and later served as a nurse at Abu Ghraib prison. This is a container for Riley’s digital pictures and fleeting traumatic memories. Images he could not fully secure or expel and entrusted to me…. This is not a book. It is an object of deployment.”

The collaboration is intended to help Riley Sharbonno resurrect buried memories and deal with some of what he went through in a war that destabilized his life. There are pictures that he does not remember taking of events that he does not remember witnessing. Photographs, once rediscovered, sometimes assuage his guilt, providing a reason for what has happened. Some of the grand half-truths about war are diluted. But there is anger, too: “I want you to see what this war did to Riley.”

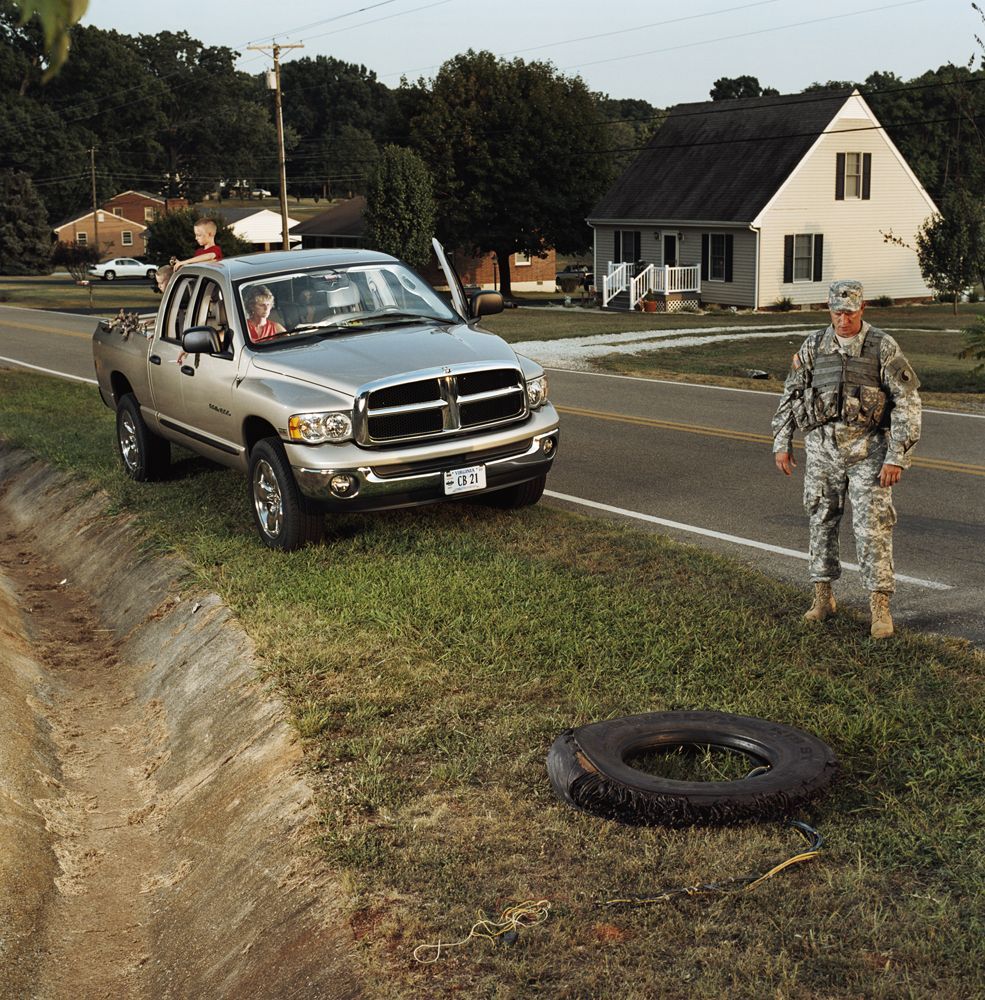

Similarly, Jennifer Karady revisits the enduring trauma of violent conflict in her collaborations with soldiers, working for about a month with each one to re-stage calamitous situations in civilian life that they had experienced in war. Finding a discarded tire on the side of the road in Virginia evokes memories of a possible IED, for instance, or looking out of a window in upstate New York while protected by sandbags recalls a vulnerability to attack—each of these pictures is made with family members participating. Karady views the procedure as potentially therapeutic for those involved, while helping to make the legacy of war somewhat more comprehensible to family and friends stateside. And unlike the imagery from so many war photographers, her pictures are not at all glamorous.

Some are also using their photographs to make sure that the violence is not forgotten by the broader society. In her project “Reframing History,” Susan Meiselas returned to Nicaragua in 2004 with nineteen murals created from her own photographs made during that country’s Sandinista Revolution twenty-five years earlier. She placed the murals at the sites where the imagery was originally made, collaborating with local communities in visualizing their own collective memories and also helping to better acquaint Nicaraguan youth with their own past. (Imagine then if it were possible to place photographs from Robert Frank’s landmark book, The Americans, made in the 1950s, on billboards around this country where the photos were made—given the critical nature of many of his photographs, it would be an extraordinary way to gauge societal change, or the lack of it.)

And some are trying to share the vagaries of war as they occur in a sort of real-time family album. Basetrack, created by Teru Kuwayama and Balazs Gardi, was an experimental social-media project that consisted of a small team of embedded photographers primarily using iPhones, which focused upon about a thousand Marines in the 1st Battalion, Eighth Marines, during their deployment to southern Afghanistan in 2010–11. They curated a news feed alongside their own efforts, employed Google Maps as an interface, wrote posts in addition to photographing, all with a view “to connect[ing] a broader public to the longest war in U.S. history,” intent on involving their audience, many of them family members, in the discussion. Trying to establish transparency, they created an editing tool for the military to censor photographs and texts that might put soldiers in danger, and asked the military to supply reasons for the censorship, which were then made visible when a viewer placed the cursor over the blacked-out section.

It was a relatively effective system, until in 2011, when the Facebook discussion became too difficult for the military to handle and the photographers were “uninvited” a month before the troops’ deployment ended. Apparently a good deal of the content that military officials found problematic was about relatively minor matters, such as parents complaining that their sons and daughters had to wear brown and not white socks on patrol. Now only the Facebook page is still active, with curated news and continuing audience discussions. One mother’s response to the project: “It has truly saved me from a devastating depression and uncontrollable anxiety after my son deployed. Having this common ground with other moms helped me so much and gives me encouragement each day.”

And then there are others who, rather than wait for the apocalypse, are attempting to see what can be done to help prevent it. In James Balog’s long-term photography project, “Extreme Ice Survey,” cameras are positioned in remote arctic and alpine areas, automatically photographing the melting of the ice to help more precisely calculate the impact of global warming, and to create a visual record of a planet in crisis. According to the EIS website: “currently, 28 cameras are deployed at 13 glaciers in Greenland, Iceland, the Nepalese Himalaya, Alaska and the Rocky Mountains of the U.S. These cameras record changes in the glaciers every half hour, year-round during daylight, yielding approximately 8,000 frames per camera per year.”

Or, if we want to make sure that the opinions of the subjects photographed are better understood, why not at times show them their image on the back of the digital camera, and ask what they think of the ways in which they are depicted, and record their voices? An even more collaborative exchange of perceptions is that between Swedish photographer Kent Klich and Beth R., a former prostitute and drug addict living in Copenhagen whom he began photographing in the 1980s. In the 2007 book Picture Imperfect, his photographs, along with case histories and images from Beth’s family album as a child, are paired with an enclosed DVD of Beth’s daily life for which she herself was the primary filmmaker.

Finally, when making pictures, maybe they can serve another, more practical function. For French artist JR’s 2008–2009 project, “28 Millimeters, Women Are Heroes,” photographs were not only used to document the faces of women living in modest dwellings in various countries, but in Kenya he began to make the oversize prints water-resistant so that when used as roof coverings the pictures themselves would help to protect the women’s fragile houses in the rainy season

Countless innovators, often working far from the spotlight, are today creating visual media that can be useful in a variety of ways. Rather than simply attempting to replicate previous photographic icons and strategies, these newer efforts are essential to revitalizing a medium that has lost much of its power to engage society on larger issues.

And then what is needed are people who can figure out effective and timely ways to curate the enormous numbers of images online from all sources—amateur and professional alike—so this imagery too can play a larger role. As badly as we need a reinvention of photography, we also will require an assertive metaphotography that contextualizes, authenticates, and makes sense of the riches within this highly visible but largely unexplored online archive.

Fred Ritchin is a professor at NYU and co-director of the Photography & Human Rights program at the Tisch School of the Arts. His newest book, Bending the Frame: Photojournalism, Documentary, and the Citizen, was published by Aperture in 2013.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com