When Ilona Szwarc and her husband moved from Poland to New York in 2008, she had never met her mother-in-law, Anna, who had made the same move decades earlier. Other daughters-in-law might have endured awkward meals or family vacations until the relationship got comfortable, but Ilona Szwarc is a photographer and she took a different approach. Although it’s only been a few years between that beginning and this Mother’s Day, Szwarc and her mother-in-law now enjoy a warm relationship. And photography helped get them there.

“We have a unique relationship where we connect through the camera and through the act of photographing,” says Szwarc. “This is a way for us to spend time together. It brings us close.”

Perhaps even closer than other daughters-in-law are to their husband’s mothers.

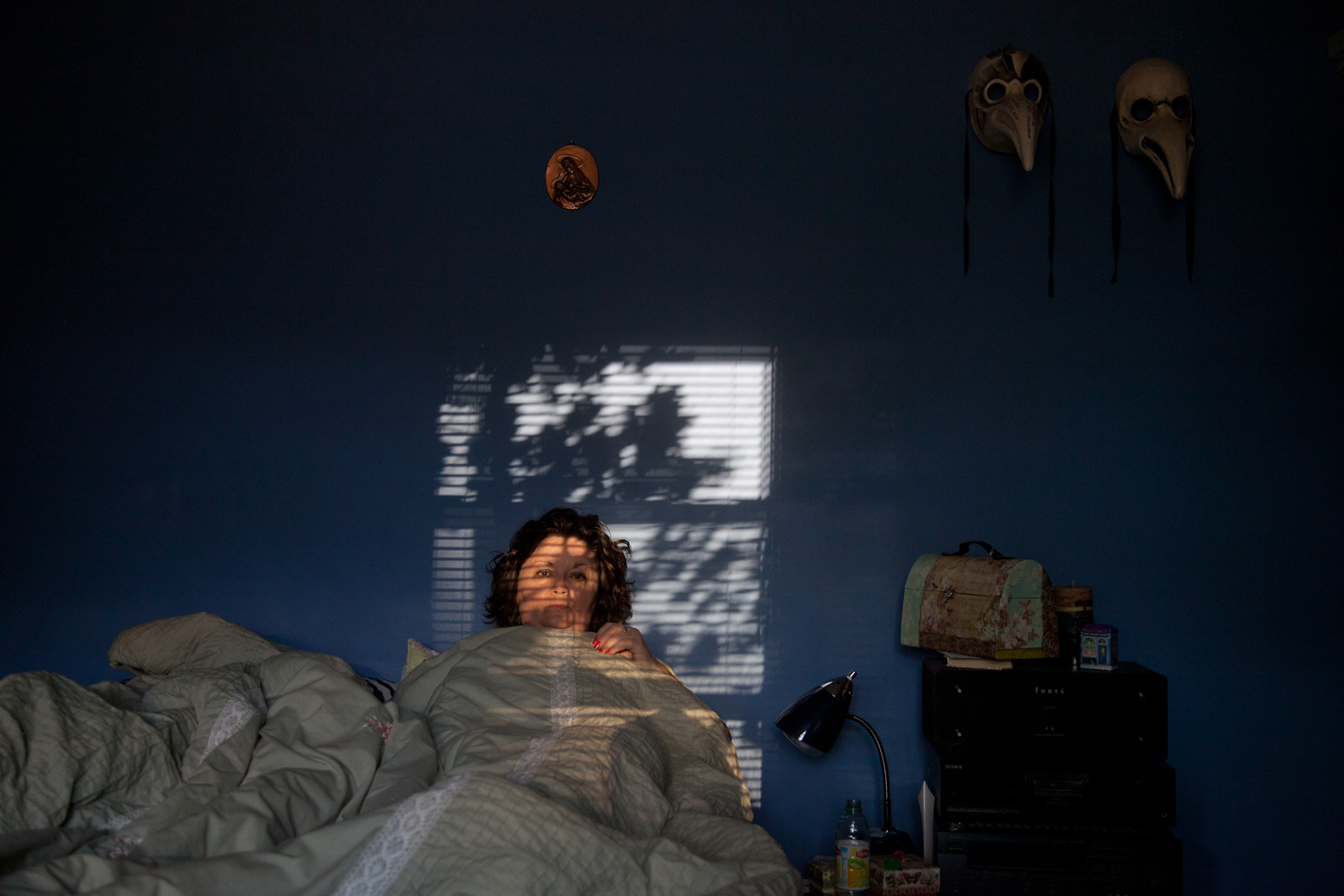

Szwarc’s pictures of Anna—whom she calls by her first name—capture a broad range of emotions. Despite their family connection, the photographer does not always present a rosy picture of Anna’s life; neither does Anna hide from the camera. Szwarc says Anna loves to be photographed and is courageously open. The pictures chronicle moments of joy, as well as instances of loneliness. That juxtaposition of fun and melancholy was manifest in the very first picture in the series: right after Szwarc suggested that they do a project together, Anna picked up a Venetian-style mask and held it in front of her face.

“I think this very much reflects her personality,” says Szwarc. “She likes to laugh, though not all of the pictures show that; she’s a free spirit; she loves costume parties. But for me, as a photographer it brings another layer of significance, thinking about identity.”

Thinking about the idea of masks—which show up several times throughout the series—was one of the ways in which the photographer grew closer to her subject. As immigrants, both Anna and Ilona have had to deal with the decision of whether, and to what degree, they want to blend in or distinguish themselves, to grapple with what it means to be a Polish woman in America. (Or a woman, period: like much of Szwarc’s other work, the Anna photographs also touch on a fascination with other sorts of masks, like beauty and appearance.) Immigration inevitably means that people become physically distant from one another. Although Anna left Poland partly to make a better future for her family, she was not able to arrange for her son—Szwarc’s husband—to join her until he was 19. (He traveled back and forth between the U.S. and Poland several times between then and 2008.) Her husband, who appears in one of the photographs, does not live in the U.S.; she has not yet fully found her place in the community of her new homeland. The process of the family coming back together is still a work in progress, and Anna’s life is often, as Szwarc’s photographs show, a solitary one.

The immigrant’s story especially stands out in the one photograph in the series that Szwarc did not take, a snapshot of Anna in front of the Statue of Liberty, taken by Szwarc’s husband Bartek Rainski shortly after his mother arrived in the United States. The composition is noteworthy—Anna’s figure and the statue’s seem to echo one another—as is its meaning for Szwarc.

“It represents Anna’s journey to fulfill her dreams and hopes for a brighter future in this country,” Szwarc says.

When it comes to Szwarc’s photographs, Anna is more concerned with the journey than with the destination. She wants to be photographed and to spend time with her daughter-in-law, but Szwarc gets the impression that when Anna sees the pictures of her own life, they seem so ordinary as to be uninteresting. Szwarc feels differently: though her period of intense work on the Anna series has finished, she says it’s an open-ended project and will continue to evolve. Just as their relationship has.

“It’s gone from not knowing someone at all,” she says, “to knowing this person very intimately, in a sense, and witnessing this person’s ups and downs, witnessing her life.”

Ilona Szwarc is a photographer based in New York City. Her work often examines gender, identity and beauty in context of American society.

Lily Rothman is a writer-producer for TIME.com.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- TIME’s Top 10 Photos of 2024

- Why Gen Z Is Drinking Less

- The Best Movies About Cooking

- Why Is Anxiety Worse at Night?

- A Head-to-Toe Guide to Treating Dry Skin

- Why Street Cats Are Taking Over Urban Neighborhoods

- Column: Jimmy Carter’s Global Legacy Was Moral Clarity

Write to Lily Rothman at lily.rothman@time.com