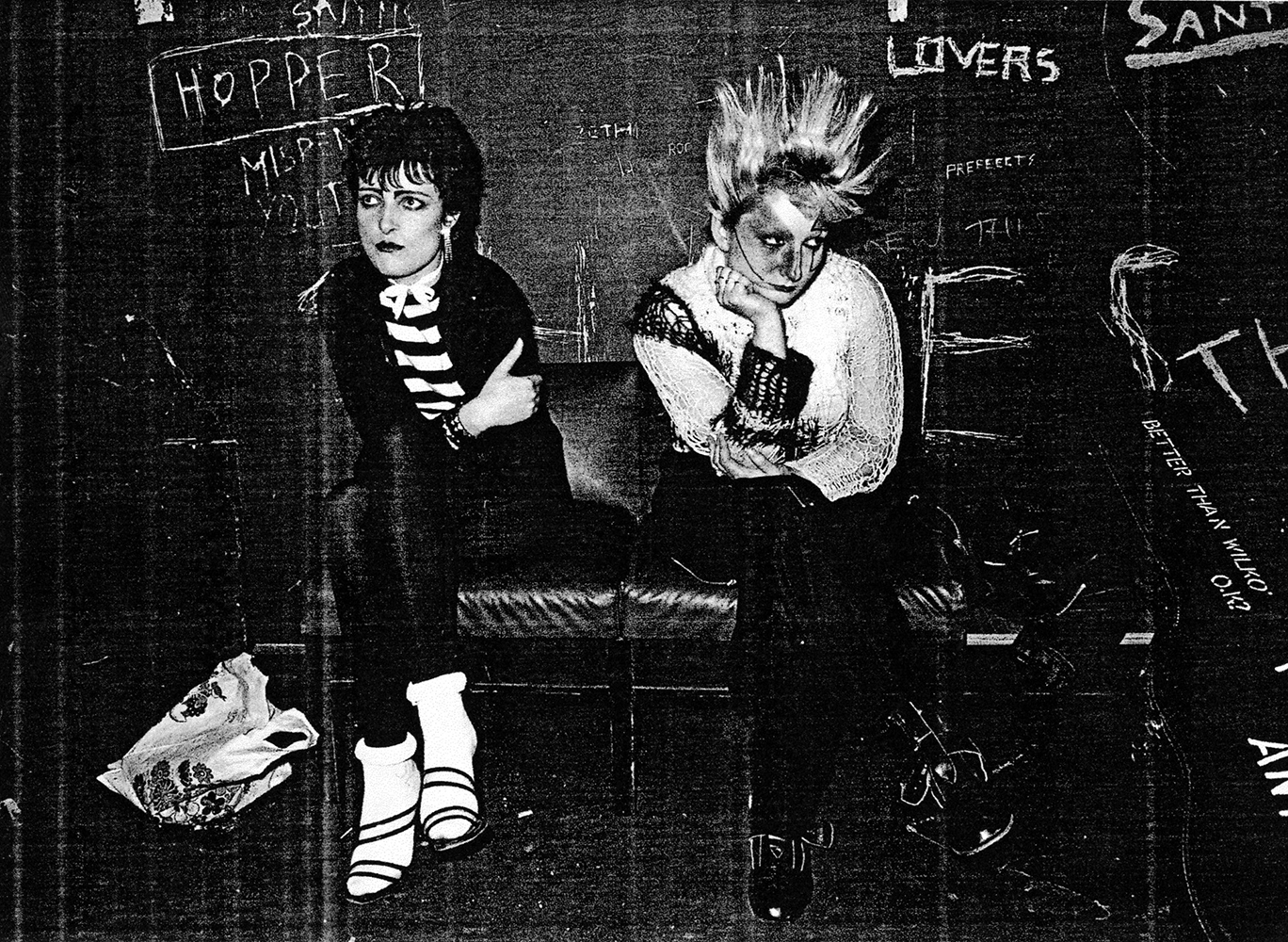

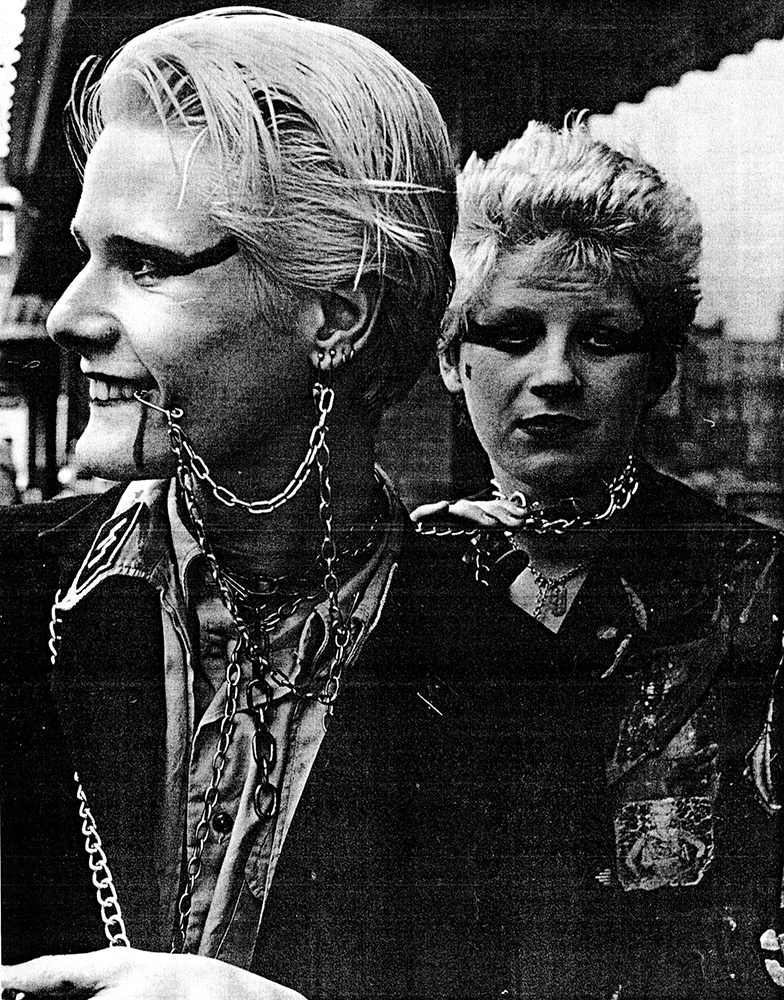

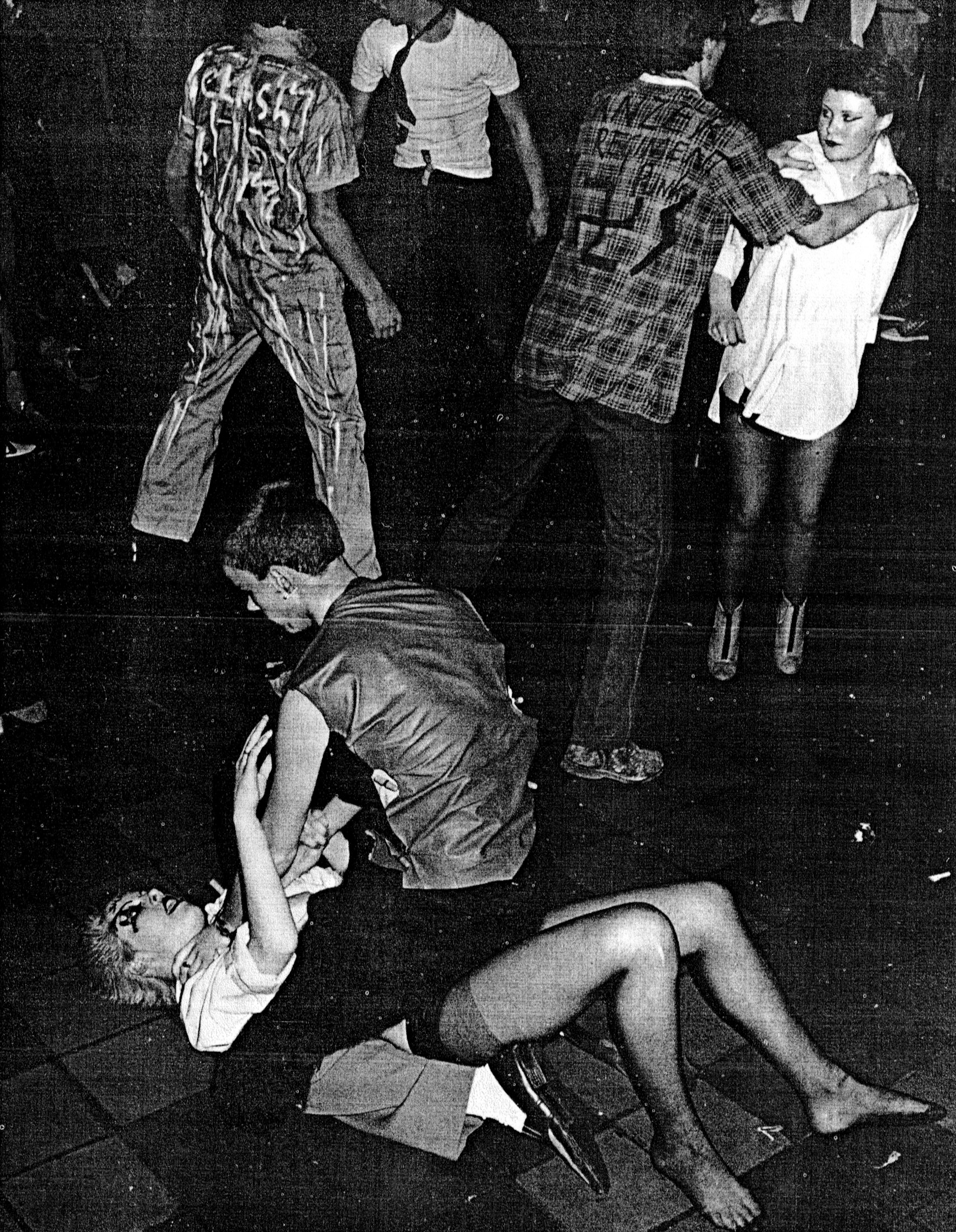

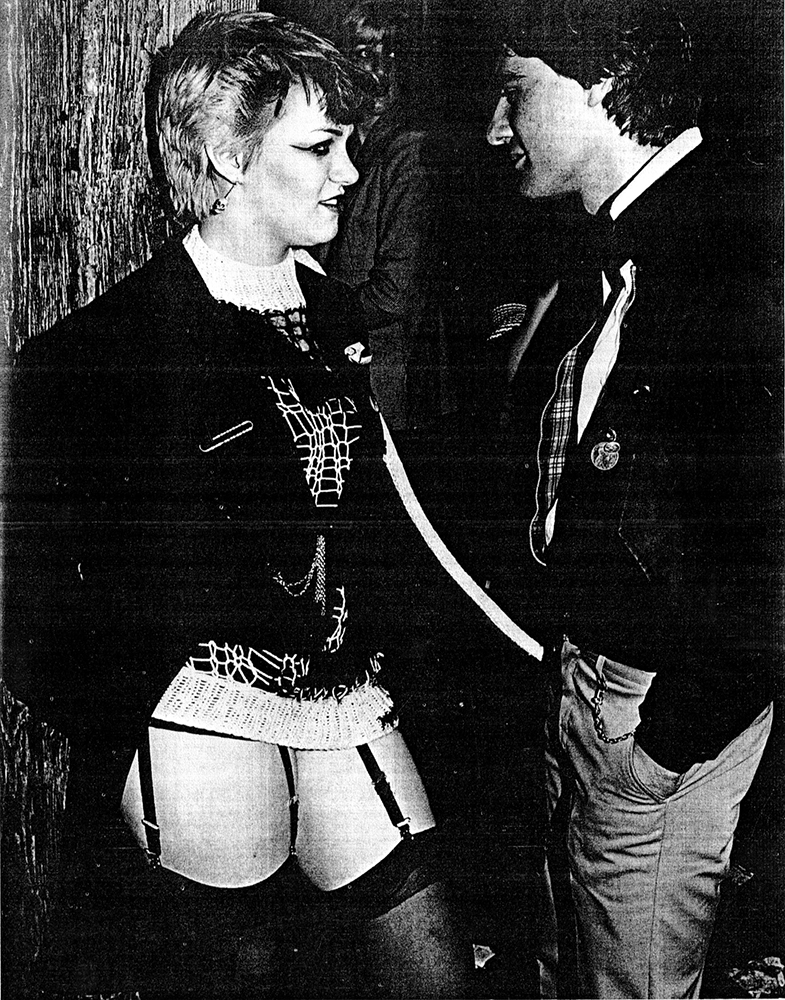

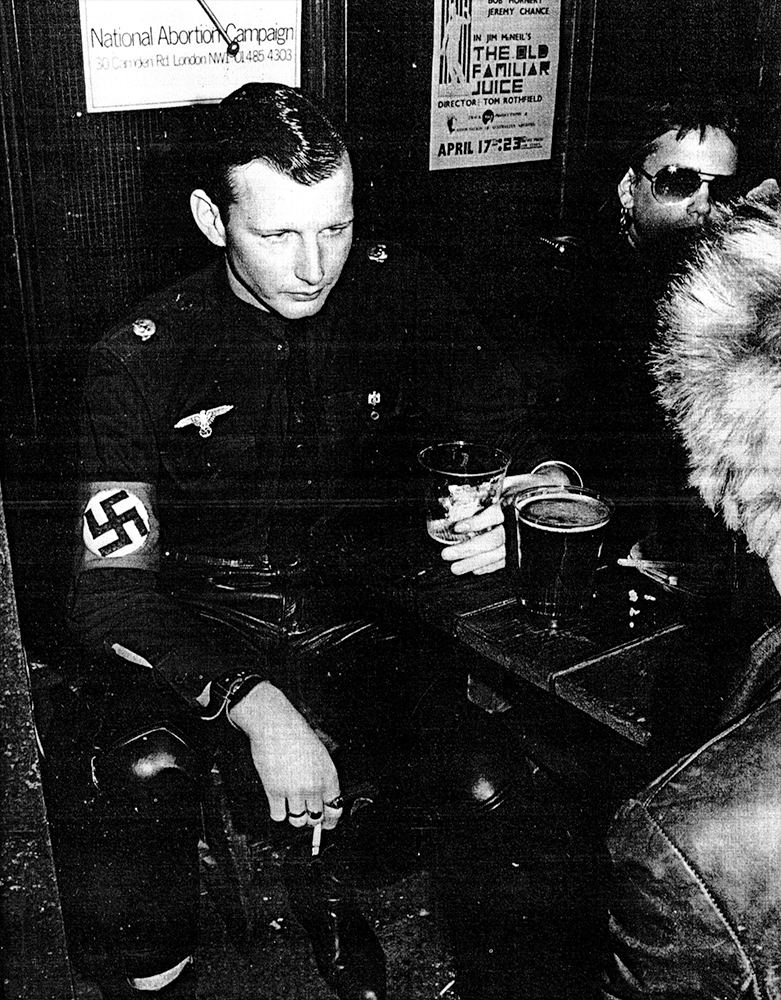

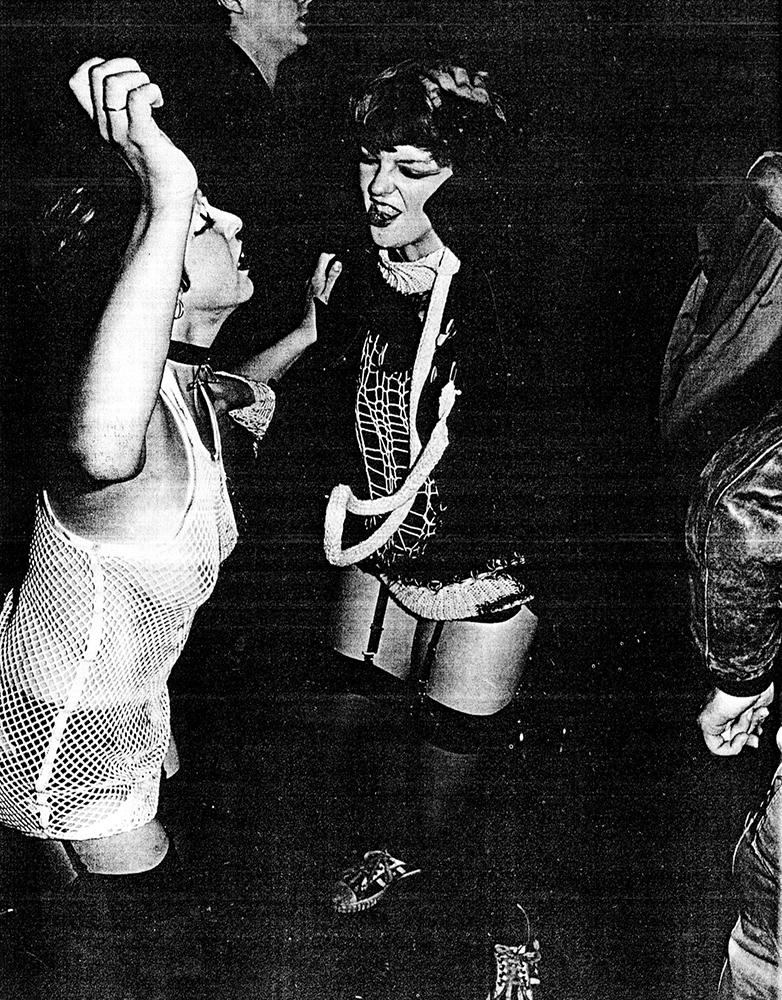

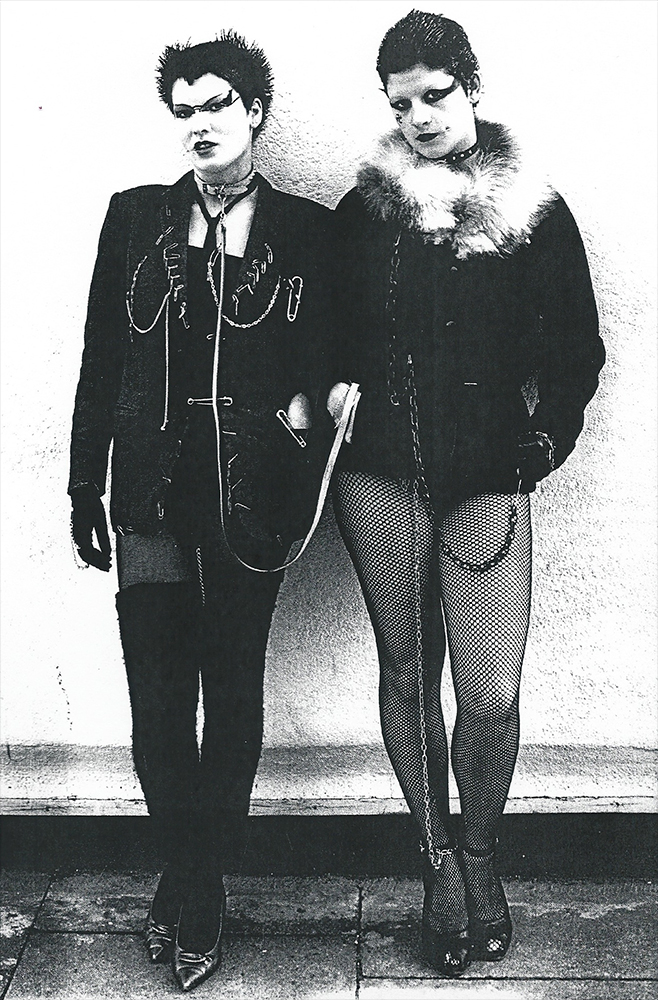

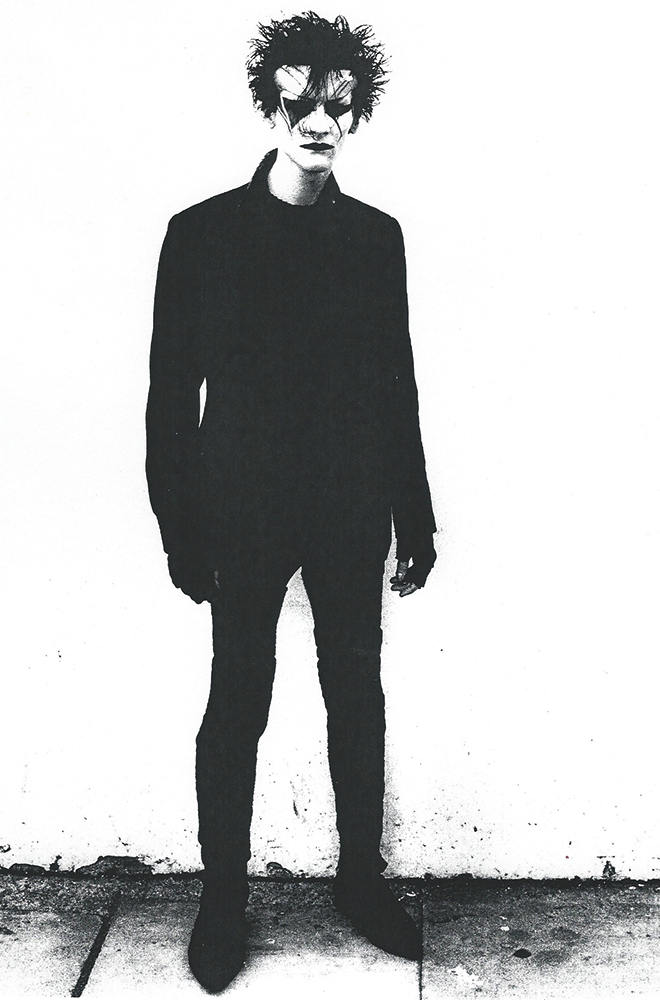

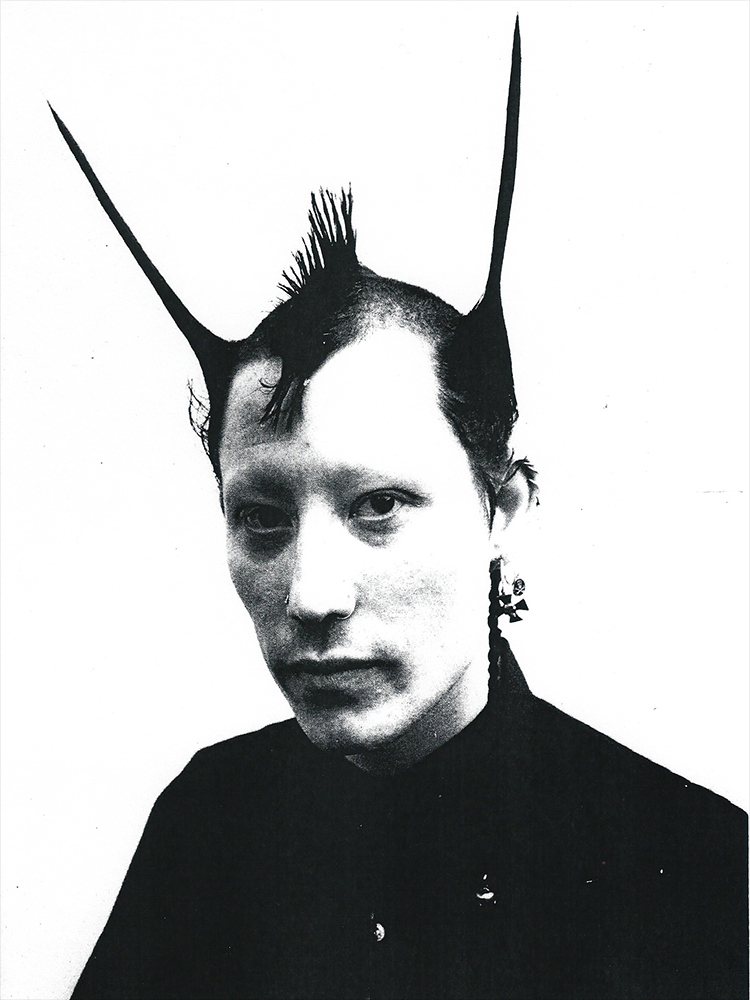

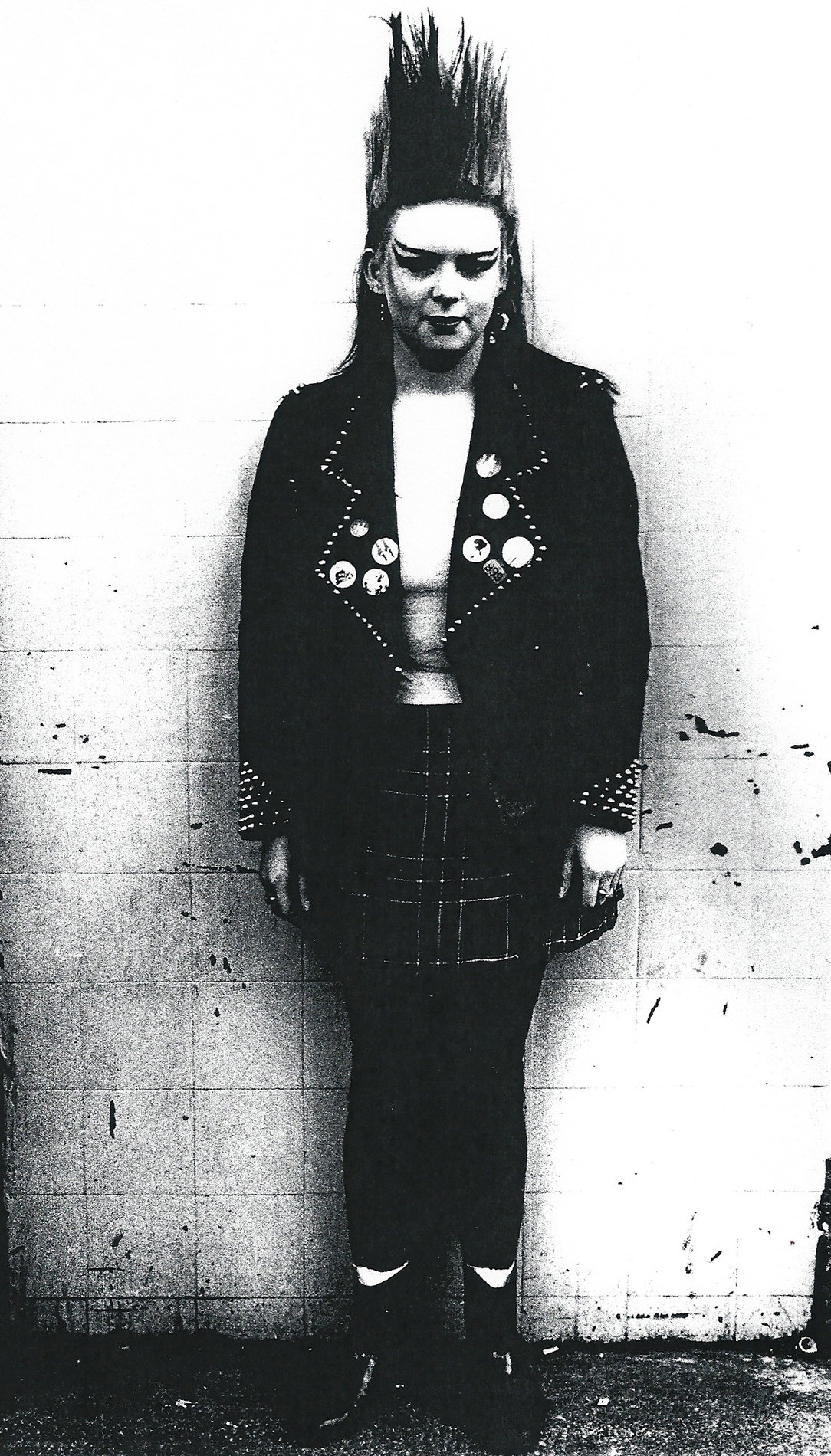

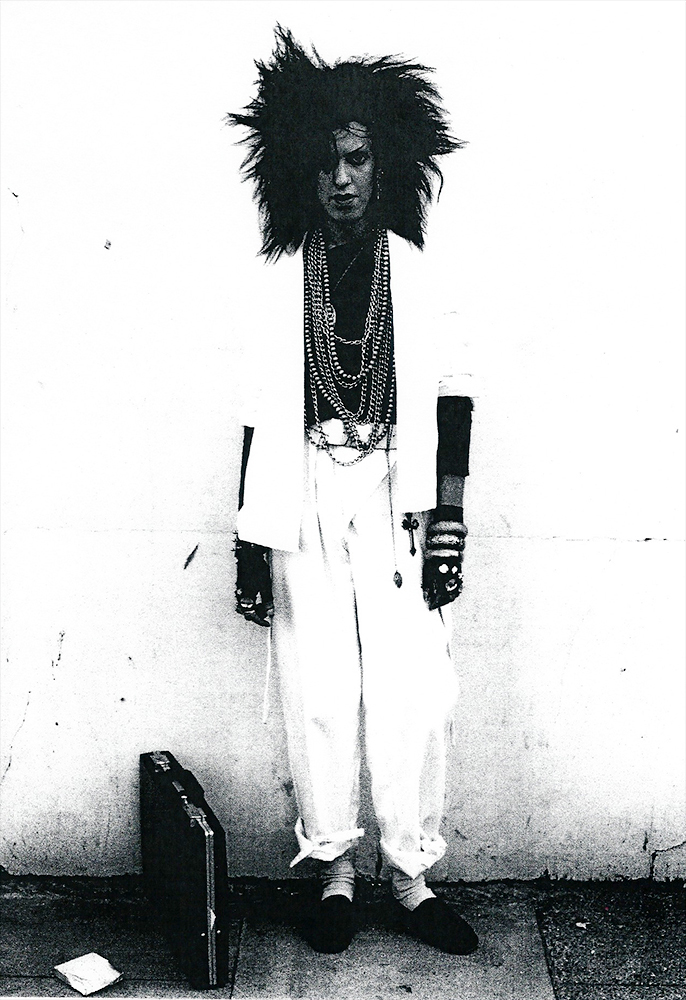

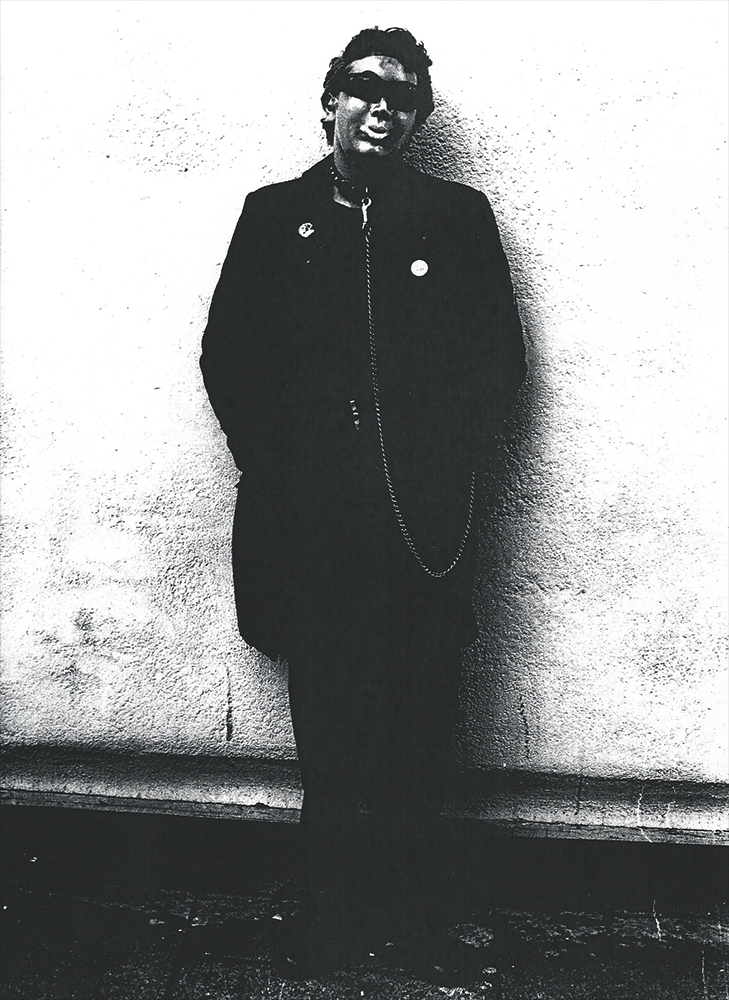

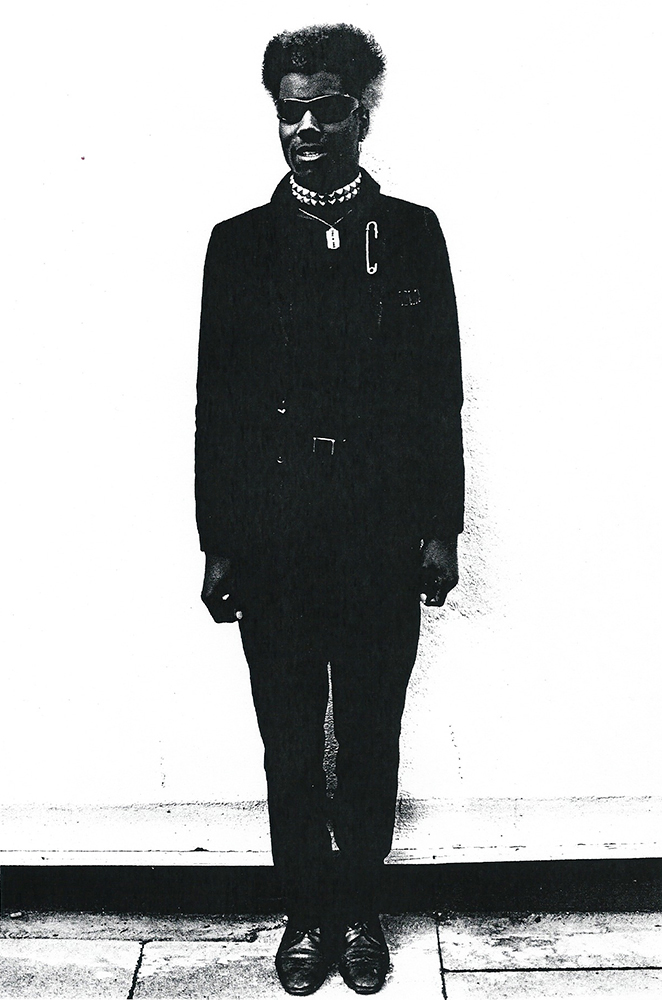

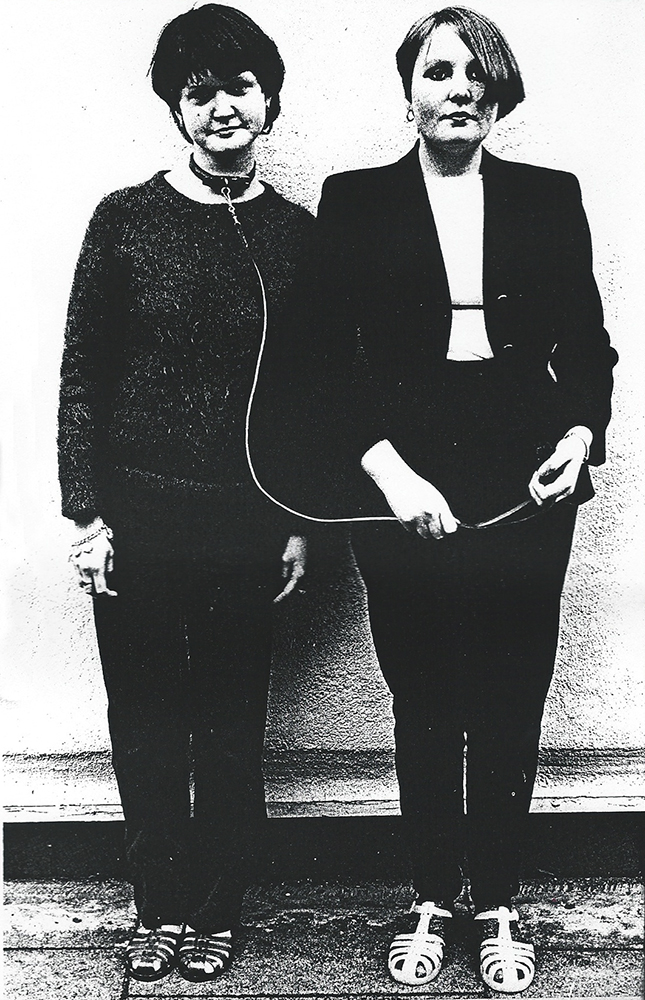

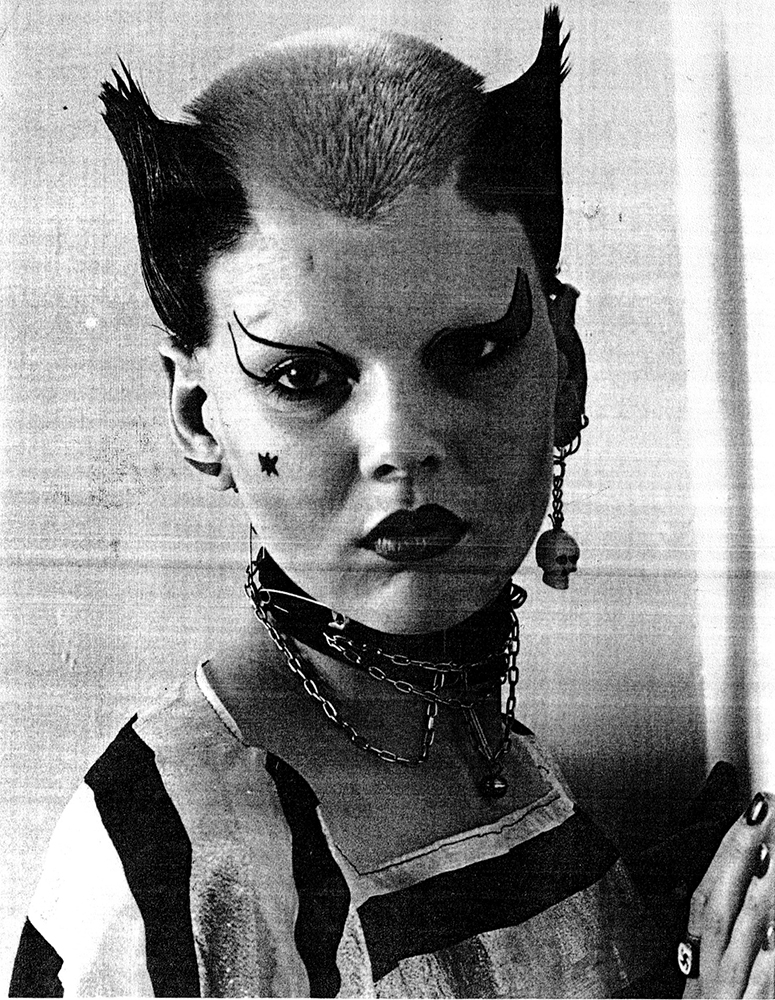

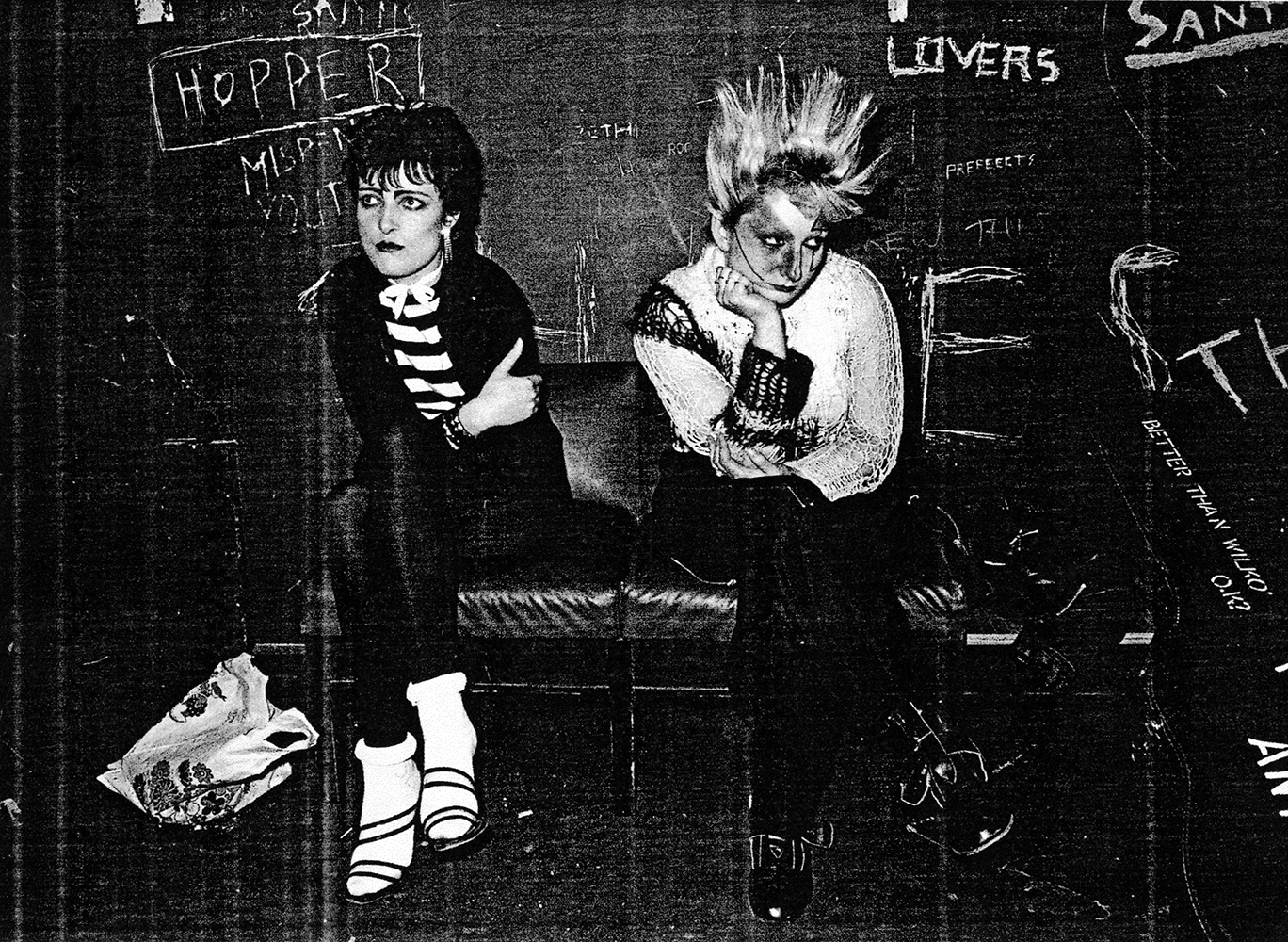

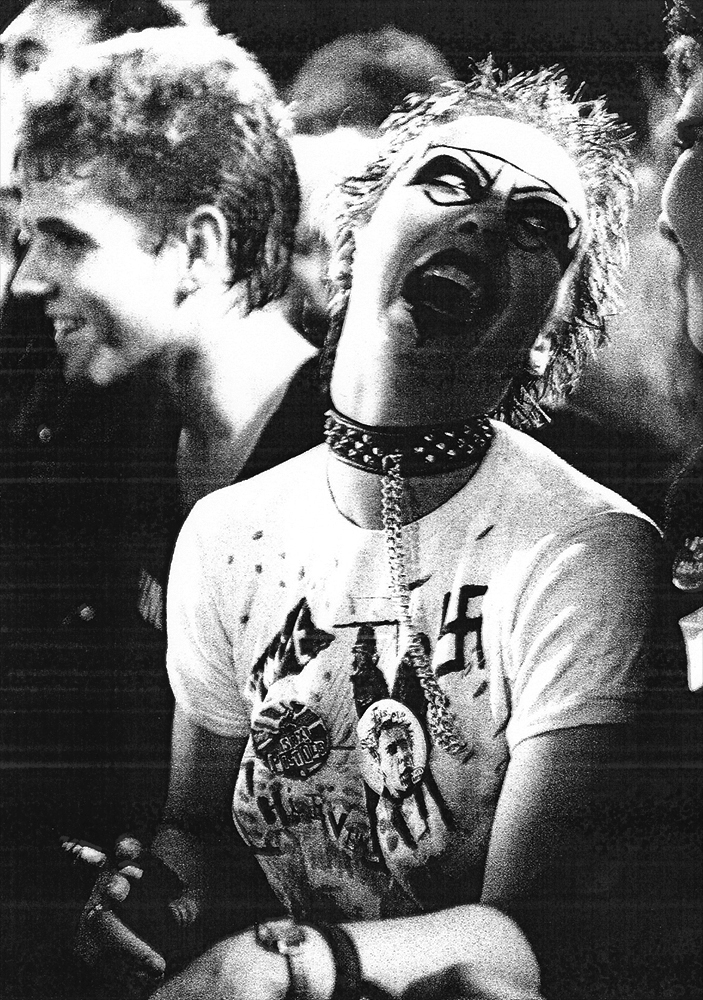

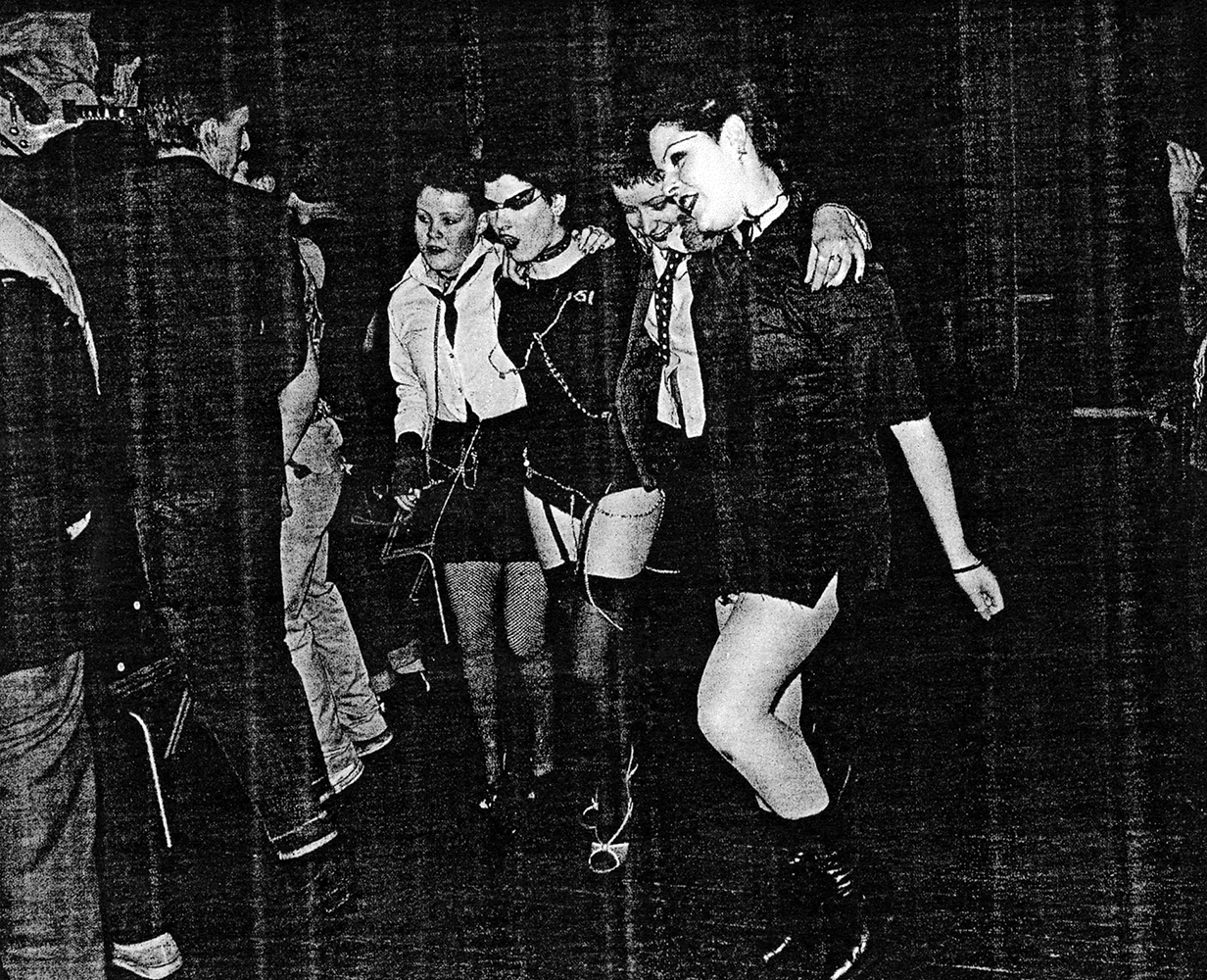

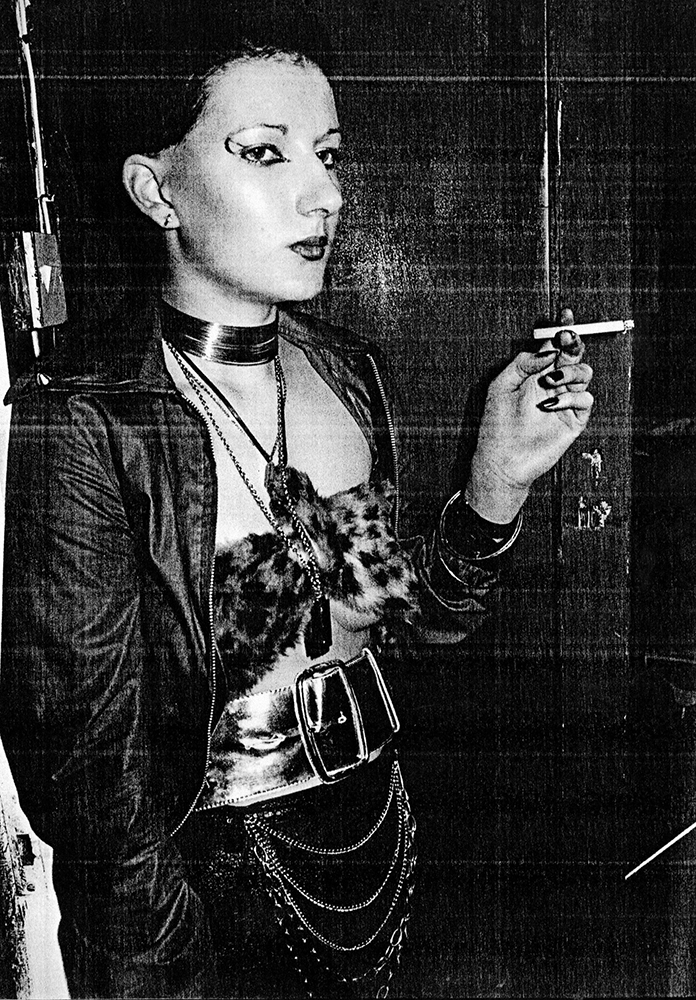

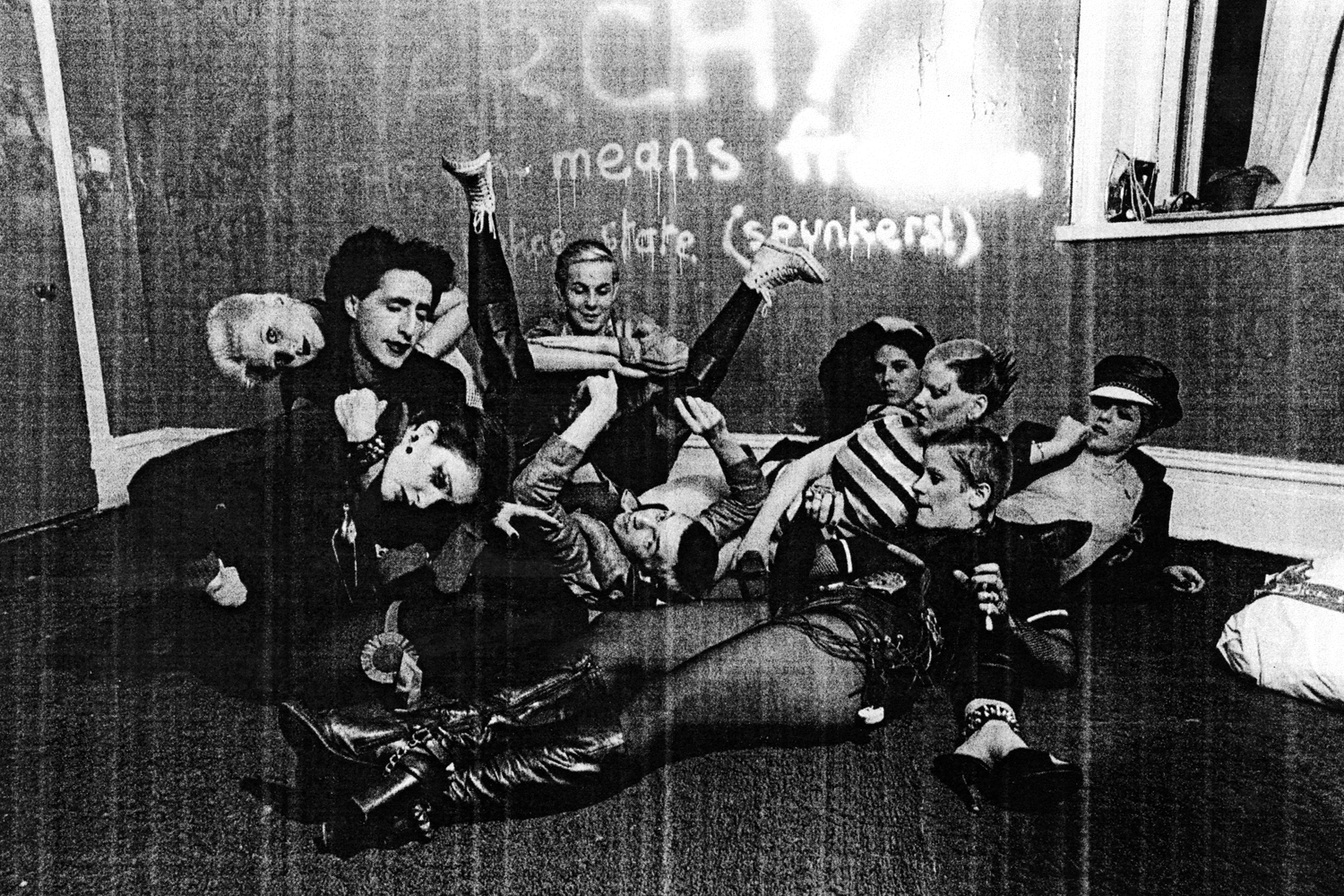

In the beginning, punk happened on the streets — a rebellious embodiment of disillusioned British youth, expressed through style and music. Where once its images were reproduced in stapled fanzines, four decades on a new exhibit at the Metropolitan Museum of Art carries punk into more rarefied surroundings. TIME looks back, through the work of three photographers — Alex Levac, Steve Johnston and Ray Stevenson — to the early days of Punk, by reproducing their gritty images in the photocopied aesthetic of the era. Below, Jon Savage writes about the movement as the introduction to the new publication PUNK: Chaos to Couture.

The many arguments that have since clustered around punk authorship and, indeed, authenticity only serve to cloak the fact that it was an impulse that crystallized into an idea and a manifesto in various cities throughout the Western world during the early 1970s. A word trace on ‘punk’ will take you through gay prison slang and 1950s juvenile delinquency to the 1960s garage rock ideal espoused with increasing frequency after the 1972 release of Lenny Kaye’s groundbreaking compilation Nuggets.

The 1960s were over. It was time for a truly 1970s rock music. But what could that be? In Paris, New York, Cleveland, San Francisco, Detroit, Los Angeles and London, young fans, writers and activists began to grope toward a definition of a new rock age. Their enemy was the spectacle, which had, by the early 1970s, successfully incorporated youth rebellion into its armory of repression. They railed against the tyranny of soft rock, the hegemony of the mellow. The forward, unitary motion of 1960s pop modernism was gone and in its place came an eclectic, restless, uprooted culture. The past was up for grabs: not just the history of postwar pop music — already thirty years old — but a gnostic tradition of outcasts and visionaries that began as far back as the late eighteenth century with the Romantics. Anything, as long as it was youthful and sharp-edged, as long as it helped the new aesthetic, the aim of which was to hone everything down to a fine point. New York was well ahead of the pack: it was both big enough to foster an independent rock scene and open to ideas from Europe. Andy Warhol and Lou Reed were always at odds with the prevailing late 1960s counter-cultural rhetoric, and their influence hung heavy: in November 1970, the week that the Velvet Underground’s Loaded was released, the performance art/rock group Suicide printed a flyer for a small show on West Broadway that read ‘Punk Music.’

The city’s biggest hope in the early 1970s was the New York Dolls, fashion-obsessed brats from Queens and Staten Island. Pop culture mavens and Anglophiles, they adopted a wardrobe that fused the wilder excesses of hippie, the androgyny of the drag queens, who were omnipresent at Max’s Kansas City and in the Warhol entourage, and the glamor of rock and roll: “It was more like ’50s gold lamé,” said New York Dolls member Sylvain.

Sylvain remembered the look: “I was sick and tired of wearing bell-bottoms. . . . then there was the whole thing with Beyond the Valley of the Dolls, and our relationship with drugs, and that fact that we were flamboyant. If you wore a little makeup, influenced in any way by the best of the late ’60s, The Doors and the Rolling Stones, you had to have sex appeal. Before we started, me and [original drummer] Billy [Murcia] used to put on makeup just to go down to the supermarket. Getting dressed up to go shopping, it was fun to do that. That’s where we were, and that’s what it was.”

Punk began with a feeling of frustration and rage and turned it into an idea that could be acted upon. Employing deconstruction and self-starter empowerment — the DIY ethic — it liberated a generation to create its own culture. In this, it returned, for a brief while, rock music back to its original teenage inspiration and function, which was to be critical, rebellious, unpalatable, to tell an existential truth otherwise denied in the culture, and to envision what the future could be.

Jon Savage is a renowned music journalist best known for his history of the Sex Pistols and punk music, England’s Dreaming. The excerpt above is republished from the exhibition catalog, Punk: Chaos to Couture, Copyright The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com