After the tragic events at the Boston Marathon, a hero in a cowboy hat emerged. Carlos Arredondo was identified as helping Jeff Bauman in a now iconic photograph by Charles Krupa that appeared on front pages around the world. In 2006 Eugene Richards began photographing Arredondo, an antiwar activist, after he lost his first son in Iraq and eventually published his story in War Is Personal. Richards spoke to LightBox producer Vaughn Wallace about his relationship with Arredondo. Richards’ answers have been condensed and edited below.

We first heard about Carlos Arredondo in 2006 as we were researching War Is Personal. We came across the website for Gold Star Families for Peace as we looked for families impacted directly by the war. We had no preconceptions about who we were including in this book about the costs of Iraq. But we knew we didn’t want to be intrusive with someone who had just lost his child. That’s a heavy thing.

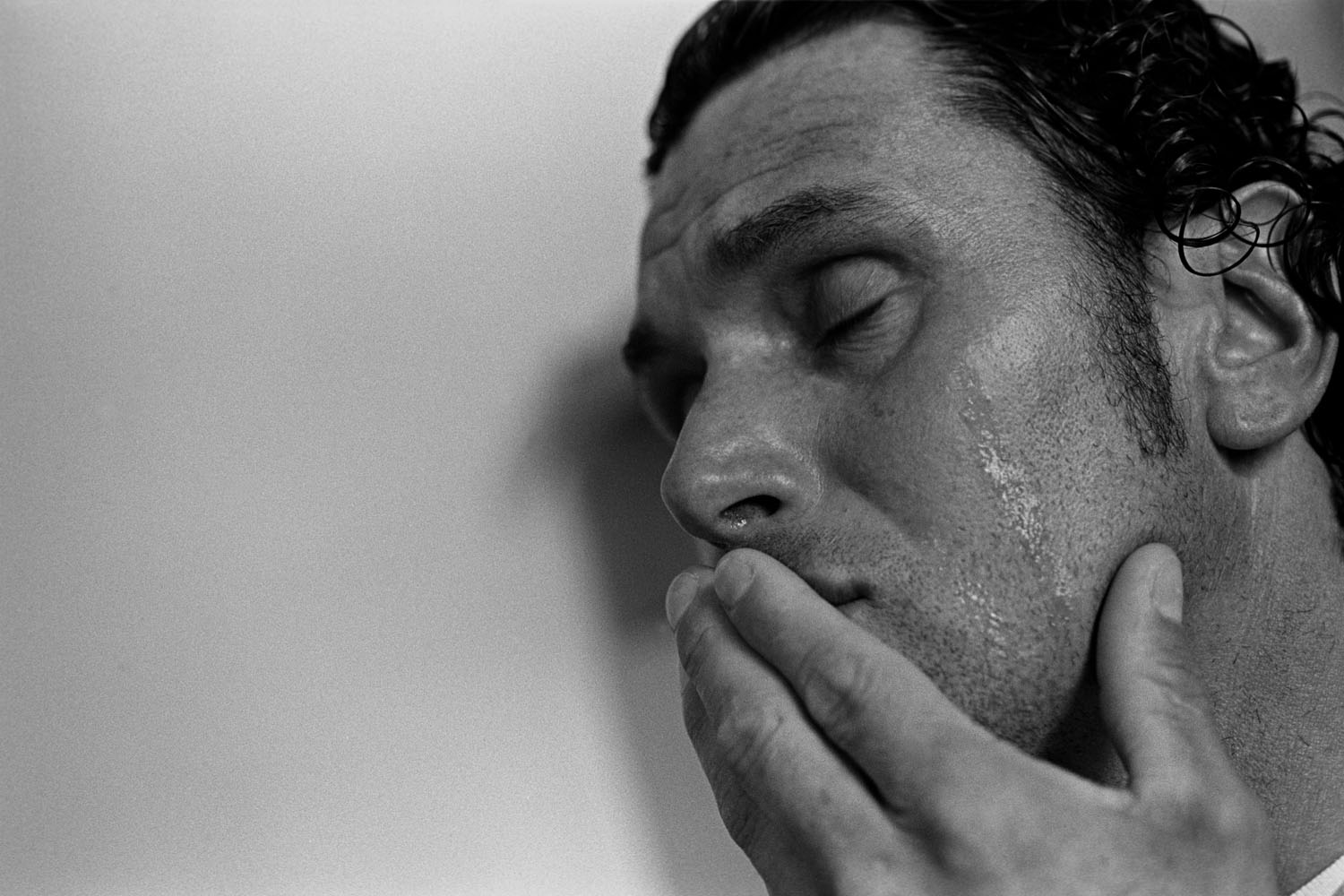

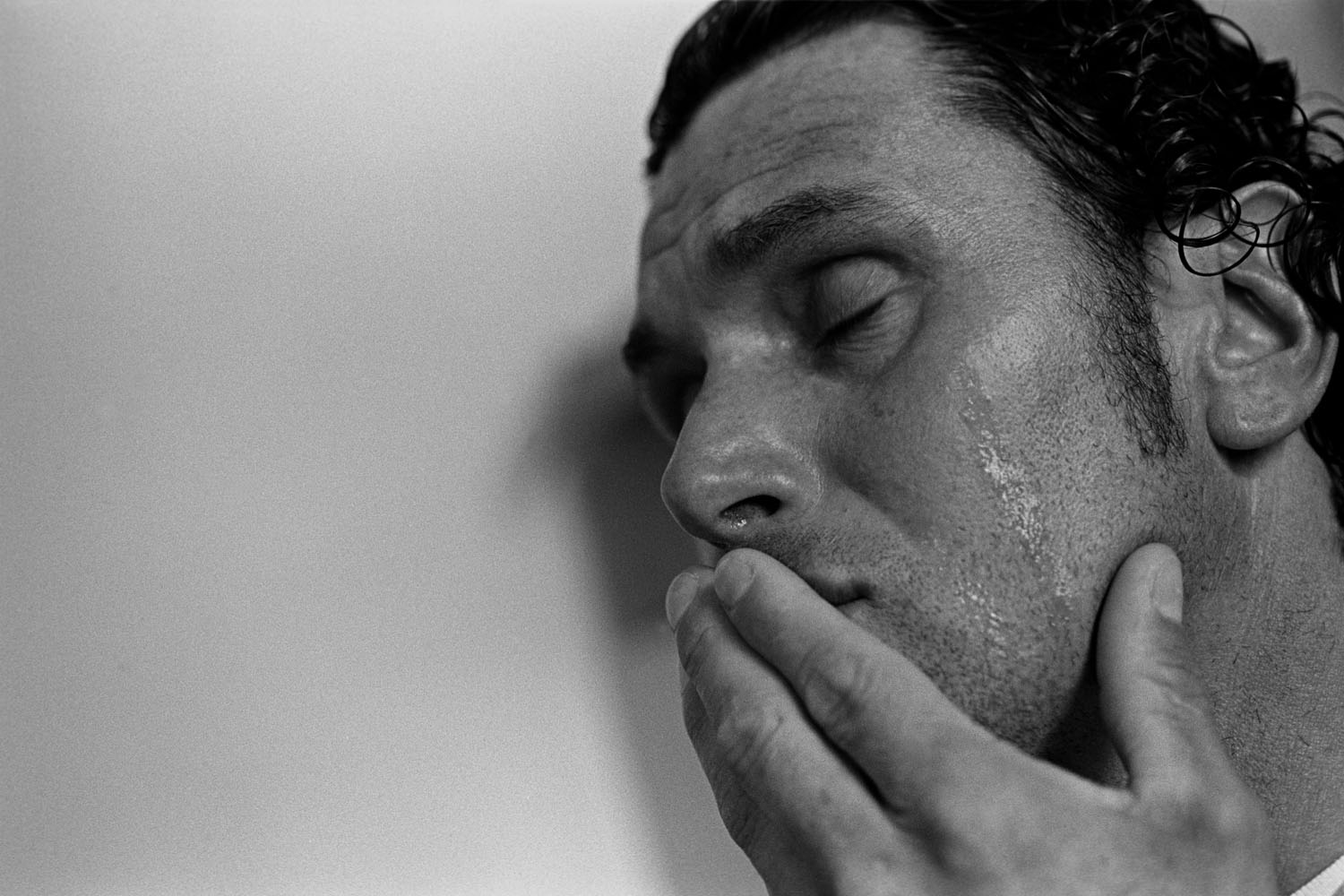

Janine (my wife) and I read a news report about someone who was quite angry, someone who accidentally lit himself on fire after learning — on his birthday — that his son was killed in Iraq. His son Alex enlisted in the Marine Corps at 17, and Carlos felt personally responsible for his life. When a group of Marines arrived at his home to notify him of Alex’s death, he became extremely emotional — as with many people I’ve photographed, it’s the ultimate nightmare.

“At that moment, not expecting those words, my world tumbled and I stopped breathing. I felt my heart go down to the ground and rush up through my throat,” Carlos later told me.

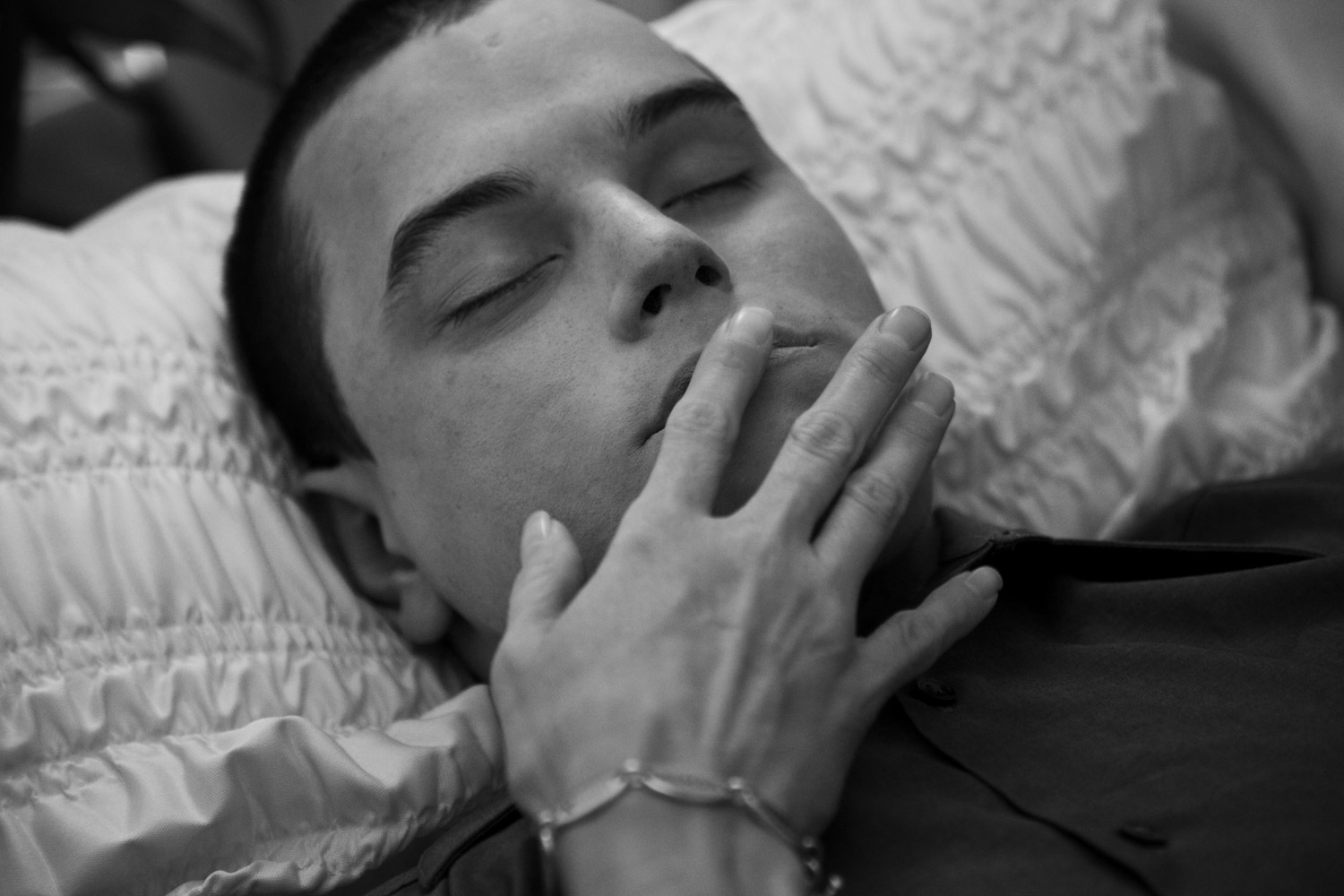

Carlos didn’t feel that the Marines allowed him enough privacy in this nightmare, so in his grief he reacted strongly, attacking the Marines’ van with a hammer before dousing it in gasoline and accidentally setting himself alight. Carlos never intended to inflict harm upon the Marines — he later apologized to them. He attended his son’s wake two weeks later on a stretcher.

Something didn’t quite read right to us — every other parent we talked to remarked about how they had felt like acting out in the way he actually did. We wanted to find out what the truth was, so that’s why we contacted him. But what we found instead was a person very emotional and reactive in the wake of a traumatic loss.

Carlos is a highly charged guy who’s always trying to do the good thing. After the death of his first son, he and his wife Melida both made a commitment to the peace movement. For years now they’ve been attending funerals of fallen soldiers and other public events and protests, work and aspiring for peace. I think it’s interrupted his ability to work. Full of passion and emotion, Melida is often the person who holds him together. In some respects, he seems to be unstoppable.

I’ve been with him as he pulls around a wagon with a photograph of Alex in a casket — an action that elicits a huge public response. Just blocks from the Boston Common, people spat on him, cursed him and taunted him for carrying a picture of a dead person in a coffin. This is something very revealing and terrible about the concept of what photographs can do. If you have the right image of carnage, you’re a hero. If you have the wrong image of the aftermath, you’re a villain.

This country reacts so strongly to those photographs — stronger even than to pictures of mortality. The casket is a metaphor for the unwatchable. People would come up and tell him he has no right to show this photo. And he would tell them that it’s his own son. It’s a conflicting image — that’s why people want it removed.

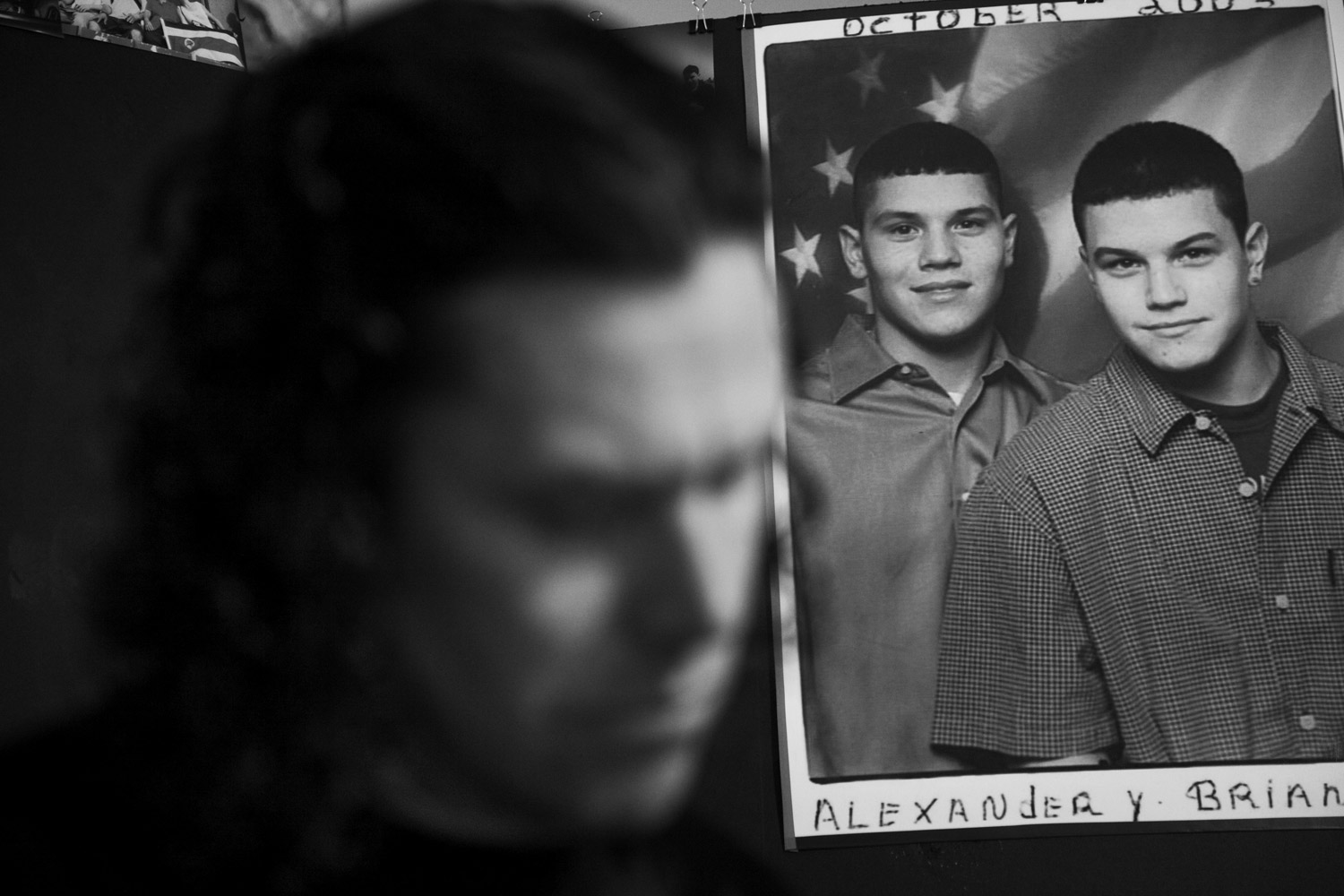

I visit Carlos and Melida periodically as friends. We don’t see each other that often, but we’re there for each other. When there’s a problem, they know that I’m there. Melida called me when Carlos’ remaining son, Brian, committed suicide in December 2011. You’re simply overwhelmed. You become incredulous because there’s nothing you can do. It’s an enormously helpless feeling. We offered to defray the cost of the funeral with the proceeds from War Is Personal.

I didn’t initially see the iconic image of Carlos from the Boston Marathon. I think Janine eventually told me it was him. Like a lot of people, it took a considerable amount of time for the true scope of this tragedy to sink in. You read a good deal about a tragedy and there’s a part of you that shuts off in direct response.

Carlos called me on Tuesday and we spoke for only a few moments. I find it ironic that people are just now starting to recognize that his life’s dedication is all about the pursuit of peace, and that it’s been that way since Alex’s death. It took an obvious act of terror to get people to realize Carlos’ story. Reporters keep saying that his life has come full circle, but I never considered it full circle. They like to see it as something very positive, which is profoundly stupid. His protest, and the last several years, have not been in a vacuum. He’s in support groups, he contacts families, he attends funerals. Even when I was photographing him for War Is Personal, Carlos was openly weeping for other people’s sons.

His story is an old story, and it’s embarrassing that we do not cover the consequences of war as we should. If a country is going to support a war, and if the media supports this country’s war, then we need to also examine the extent of this war at home and abroad. I hope this profoundly changes his life so that people give him the support he needs.

Maybe now people won’t spit on him or taunt him as they did before.

Richards is an award-winning American photographer. See more of War Is Personal at WarIsPersonal.com.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com