There’s a line from Henry David Thoreau that’s an old favorite of environmentalists: “In wildness is the preservation of the world.” Not many people have taken that idea so much to heart as the great Brazilian photographer Sebastião Salgado, who spent much of the past nine years trekking to the last wild places on earth to take the pictures collected in his new photography book, Genesis (Taschen; 520 pages), a window into the primordial corners of creation.

The Genesis project grew out of two dilemmas in Salgado’s personal life. In the late 1990s, his father gave him and his wife Lélia the Brazilian cattle ranch where Salgado, now 69, spent his childhood. He remembers the place in those days as “a complete paradise, more than 50% of it covered with rain forest,” he told Time on the phone from his home in Paris. “We had incredible birds, jaguars, crocodiles.” But after decades of deforestation, the property had become an ecological disaster: “Not only my farm, the entire region. Erosion, no water—it was a dead land.”

By 1999, Salgado was also completing Migrations, a six-year photographic chronicle of the human flood tides set loose around the world by wars, famines or just people searching for work. The project took him to refugee camps and war zones and left him wrung out physically and emotionally. “I had seen so much brutality. I didn’t trust anymore in anything,” he says. “I didn’t trust in the survival of our species.”

So as a kind of dual restoration project—for himself and his Brazilian paradise lost—Salgado and his wife began reforesting his family property. There are now more than 2 million new trees there. Birds and other wildlife have returned in such numbers that the land has become a designated nature reserve. As his personal world regenerated, Salgado got an idea: For his next project, why not travel to unspoiled locales—places that double as environmental memory banks, holding recollections of earth’s primordial glories? His purpose, Salgado decided, “would not be to photograph what is destroyed but what is still pristine, to show what we must hold and protect.” He likes to quote a hopeful statistic: “45% of our planet is still what it was at the beginning.”

As part of the Genesis project, Salgado has made 32 trips since 2004, visiting the Kalahari Desert, the jungles of Indonesia and biodiversity hot spots such as the Galápagos Islands and Madagascar. He hovered in balloons over herds of water buffalo in Africa (“If you come in planes or helicopters you scatter them”). He traveled across Siberia with the nomadic Nenets, people who move their reindeer hundreds of miles each year to seasonal pasture. “I learned from them the concept of the essential,” he says. “If you give them something they can’t carry, they won’t accept it.”

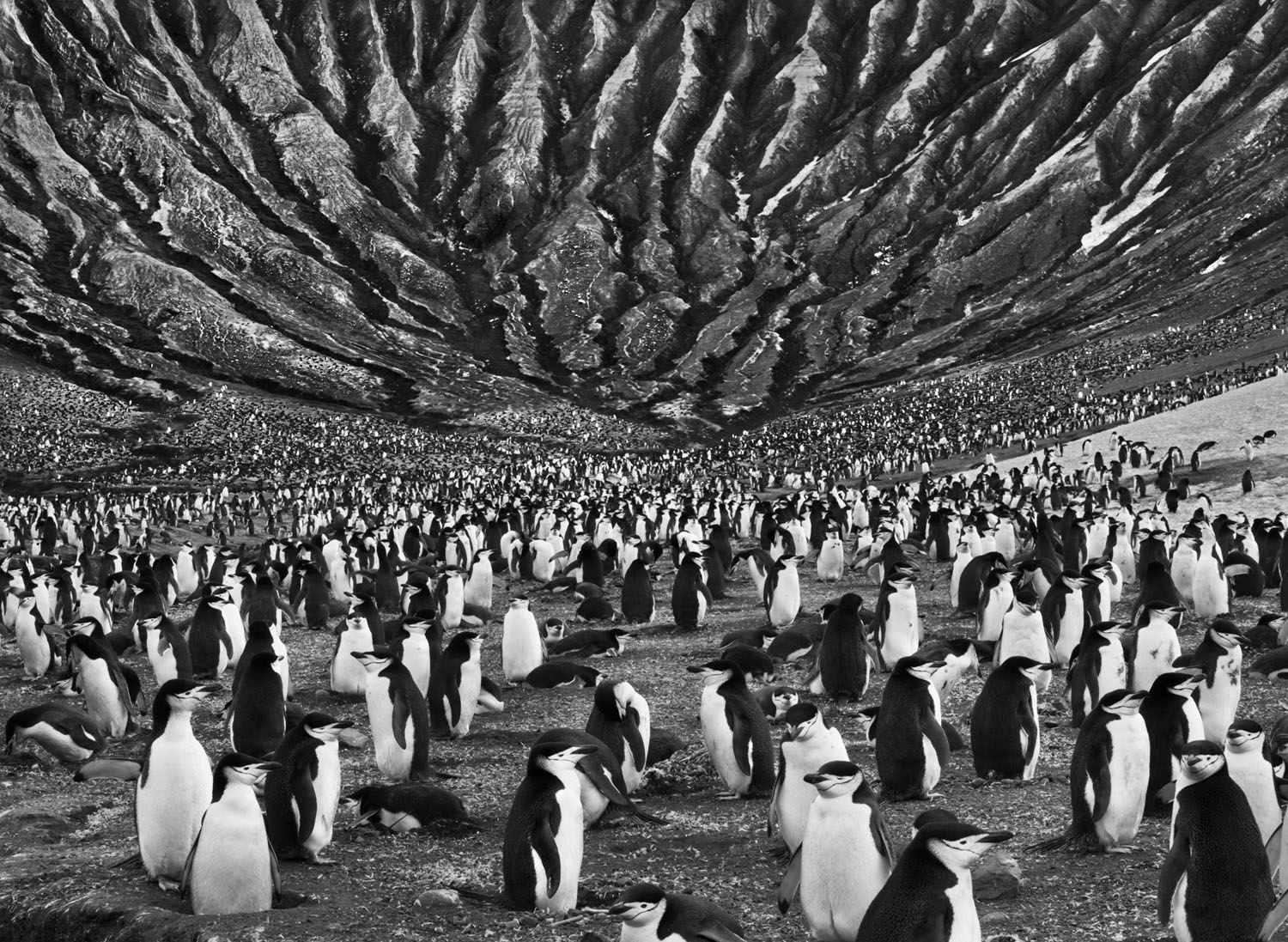

Traveling to the Antarctic and nearby regions, Salgado found vast flocks of giant albatrosses off the Falkland Islands and “the paradise of the penguins” on the South Sandwich Islands. “Islands at the end of the world,” Salgado calls them. “Or as we say in Brazil, ‘where the wind goes to come back.’” And where Salgado went too and came back with glimpses of paradise in peril—but not lost, not yet.

Sebastião Salgado is a Brazilian documentary photographer living in Paris. He has produced several books, and his work has been exhibited extensively around the world. His latest work, Genesis, premieres at The Natural History Museum in London on April 11, on view through Sept. 8, 2013. The exhibition will have its North American premier at the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto, Ontario, Canada from May 1 through Sept 2.

Richard Lacayo is an art critic and editor-at-large at TIME.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com