“[In nature] we may even glimpse the means with which to accept ourselves. Before nature, what I see does not truly belong to anyone; I know that I cannot have it, in fact, I’m not sure what I’m seeing.” —Emmet Gowin

The allure of the American West has captivated photographers since the earliest days of the medium. Photography was used as a tool to decipher the vastness of the new and unknown frontier. One can see a rich photographic form of manifest destiny stemming from pioneering documentarians like Timothy O’Sullivan in the 1800s to preservationists like Ansel Adams in the 1960s. Although the intentions of these photographers have shifted over time, the landscape has provided consistent inspiration for our deepest desires. In more recent history, our concerns about our footprint on the environment have led photographers to investigate deeper than what’s easily accessible.

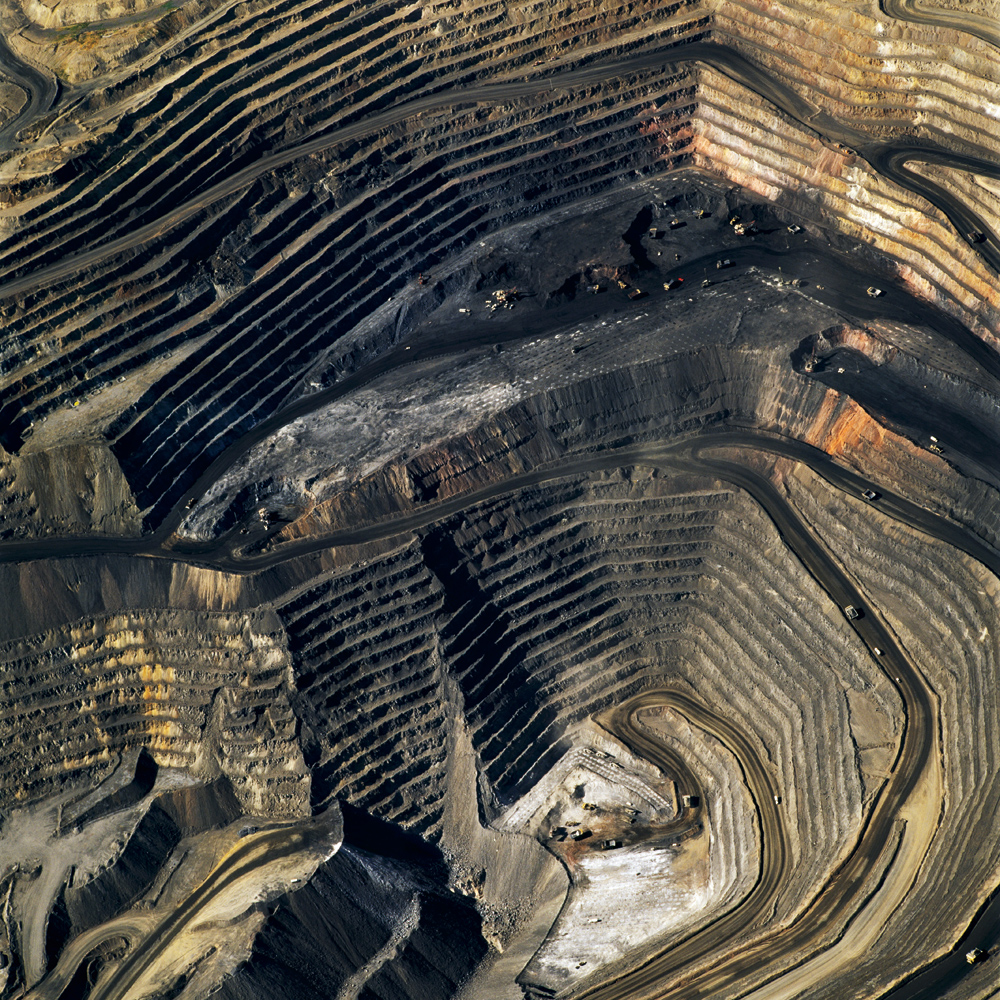

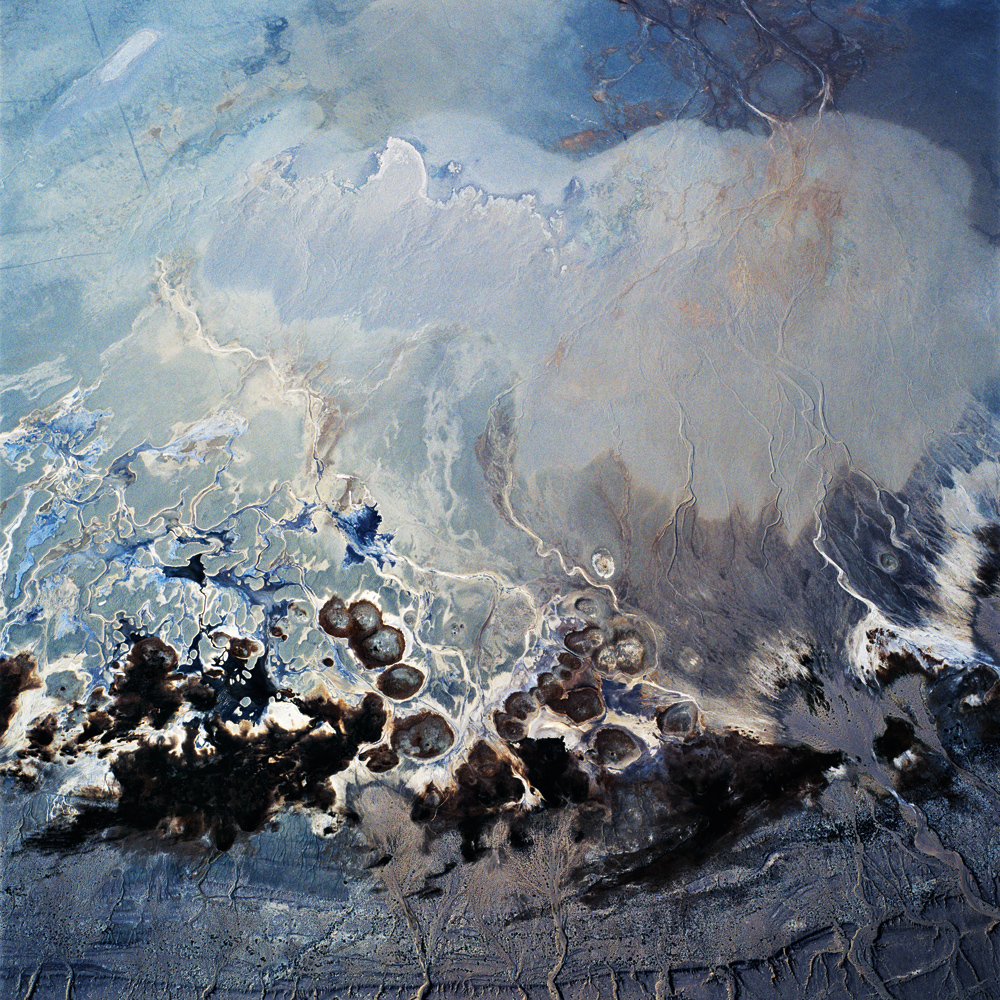

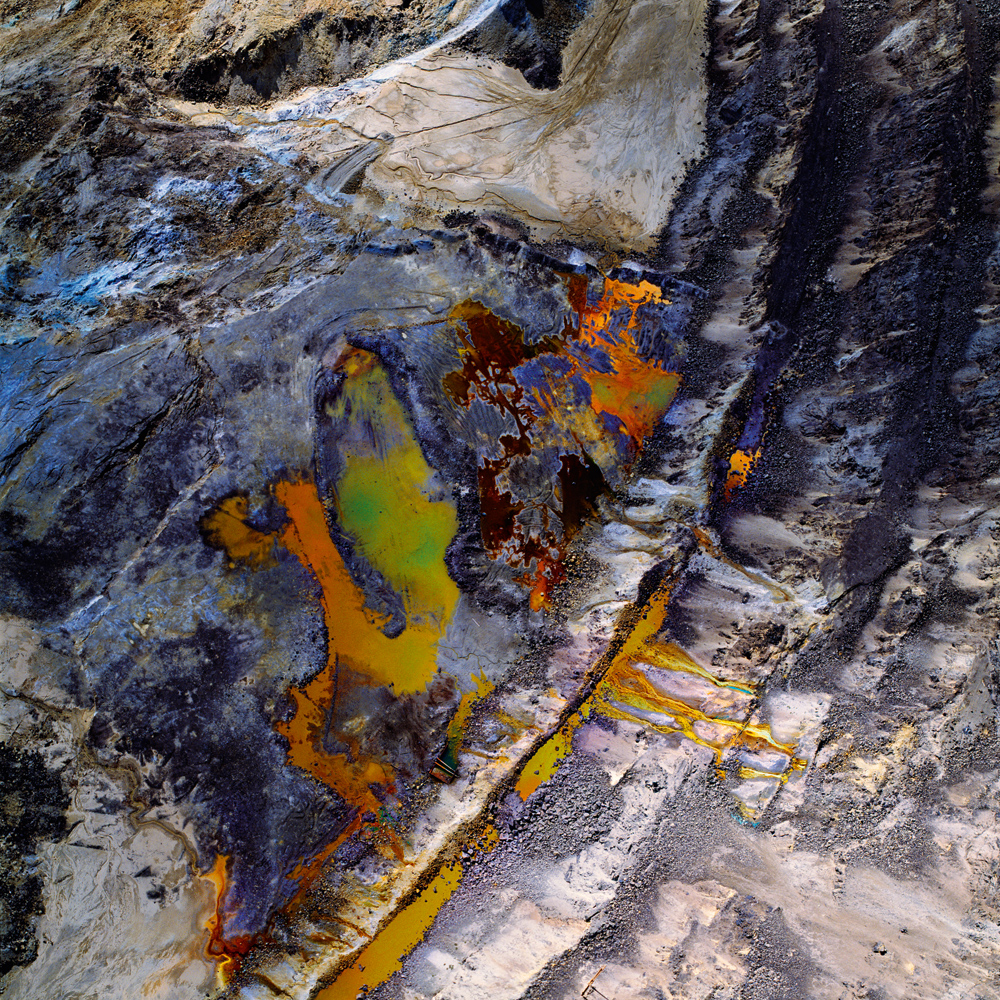

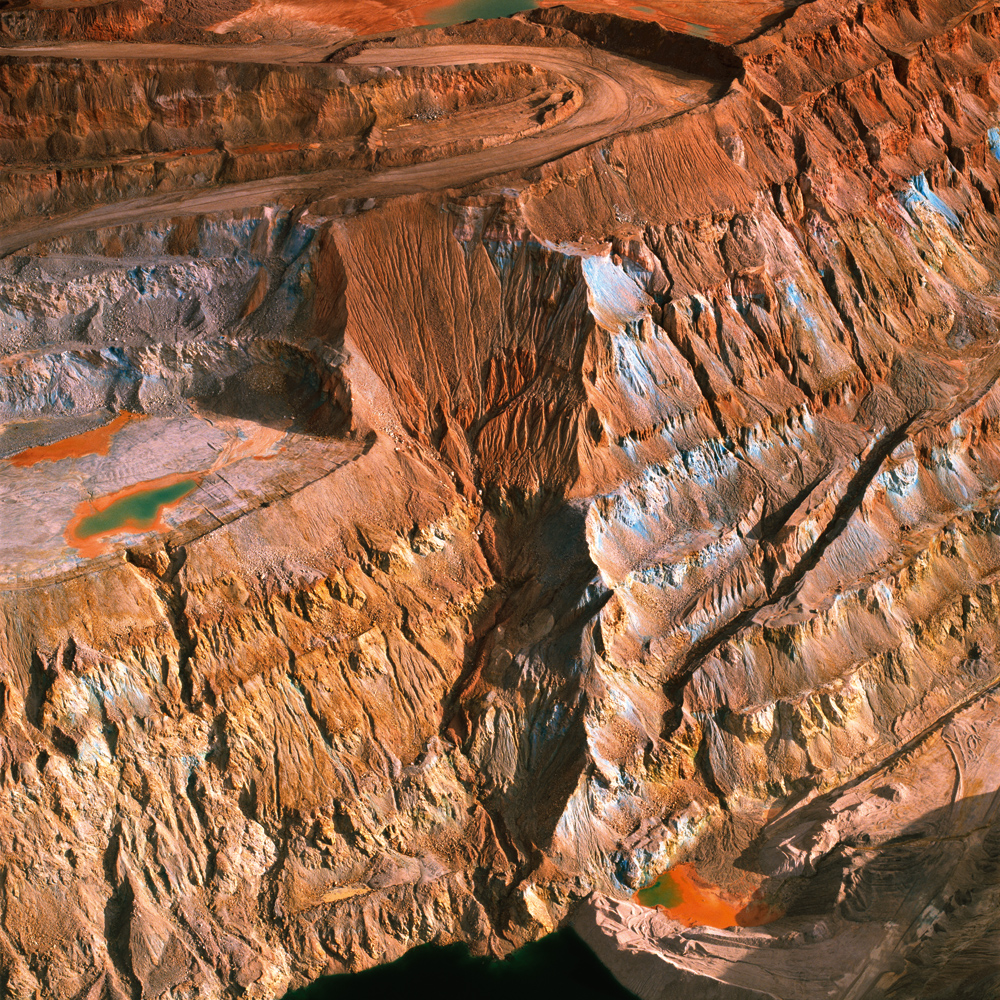

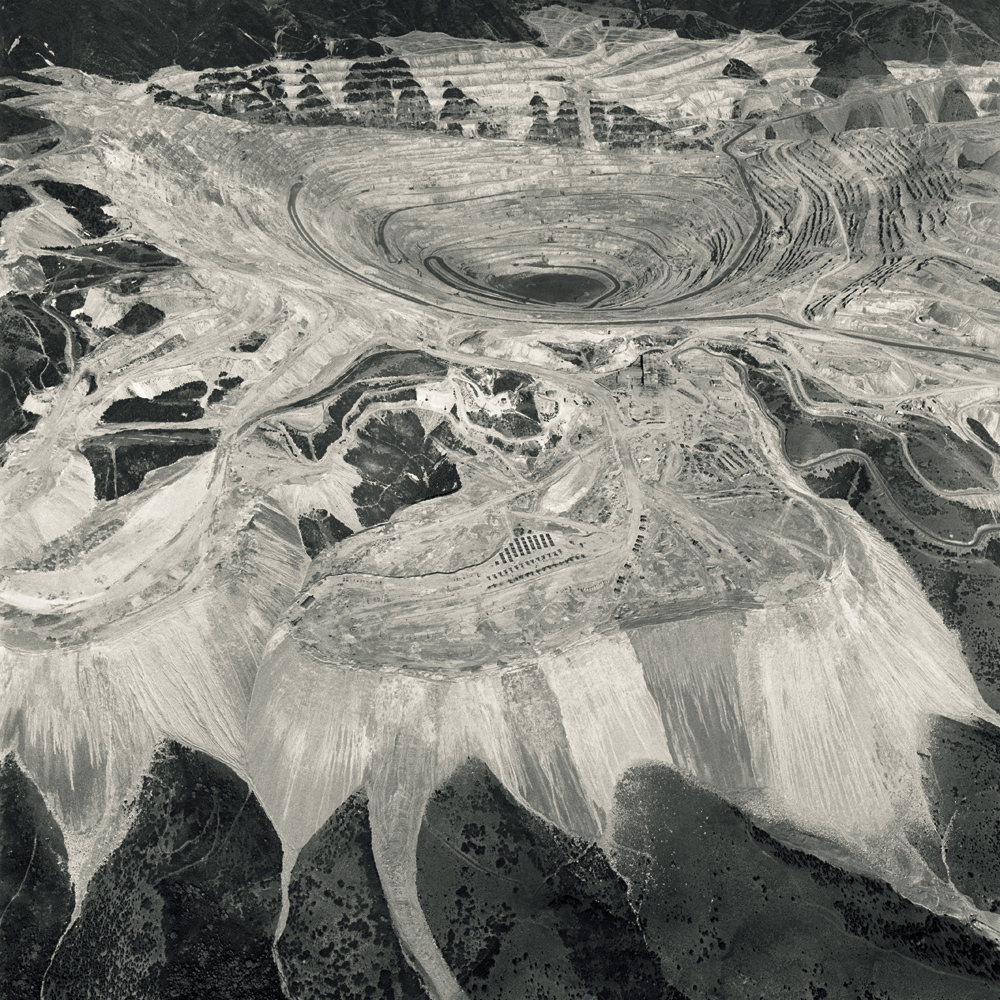

David Maisel is a photographer of the current wave of contemporary artists concerned with hidden land — remote sites of industrial waste, mining, and military testing that are not yet indexed on Google Maps. His latest book, Black Maps: American Landscape and the Apocalyptic Sublime (Steidl), observes the land from a god-like perspective of the sky and with an obsession with environmental destruction.

“The original impetus for the work was informed by looking really closely at 19th-century exploratory photography,” explains Maisel, “and then, an arc through the New Topographics work of the 70s.” He cites the work of iconic black-and-white image makers like Lewis Baltz and Robert Adams — photographers who focused on man-altered landscapes — but felt inspired to “push it further.”

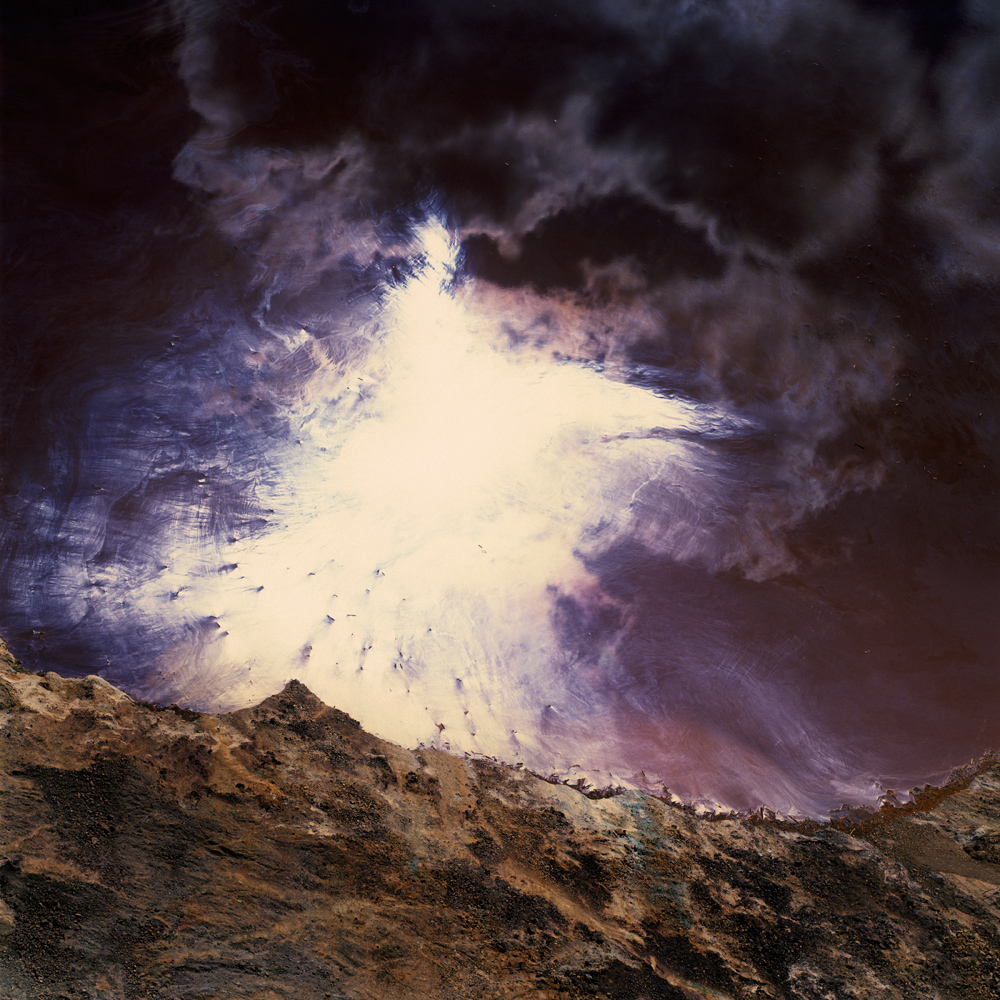

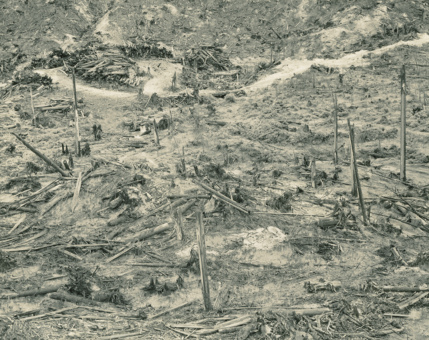

This epic project began almost thirty years ago in a plane over Mount St. Helens. Maisel, a 22-year-old photography student, was accompanying his college professor, Emmet Gowin, with his work. “That experience of being at Mt. St. Helen’s was really formative,” says Maisel. “I don’t even know if I’d be a photographer. It was an essential moment for me.”

Flying in to view the crater of the volcano formed by the extreme force of Mother Nature, he photographed a large swath of deforestation, something the young photographer had never seen growing up in the suburbs of Long Island, N.Y.

“As a kid at that point who had grown up in the suburbs of New York, I just never had seen a landscape put to work in that way by industry. Especially on that scale,” says Maisel. The phenomenal destruction revealed a conflict in modern life that he’s been fixated on since.

In the 1980’s, talking about the environment through art seemed out of step with the dialogue that was happening around Maisel as a young art student. Looking back, his formative work now stands somewhere between classic documentary and abstract expressionism. “Just bringing up Robert Smithson (the pioneering land artist) makes me remember. When I first got interested in him in the early 80’s, that’s not where the art world was at all. And it’s not where this society was at all. This idea of looking at the environment and changes to the environment, was like, ‘oh, that’s ecology, that died in the 60s, we’re done with that.’”

In no way did that attitude derail his fascination in the environment — instead, he began creating an artistic dialogue in nature as the inspiration. But it’s Maisel’s distinct intentions and conceptualization that separates the photographer from your average eco-activist, who’s motivation to shoot may be based in a desire to preserve natural spaces or reveal the evils of industry.

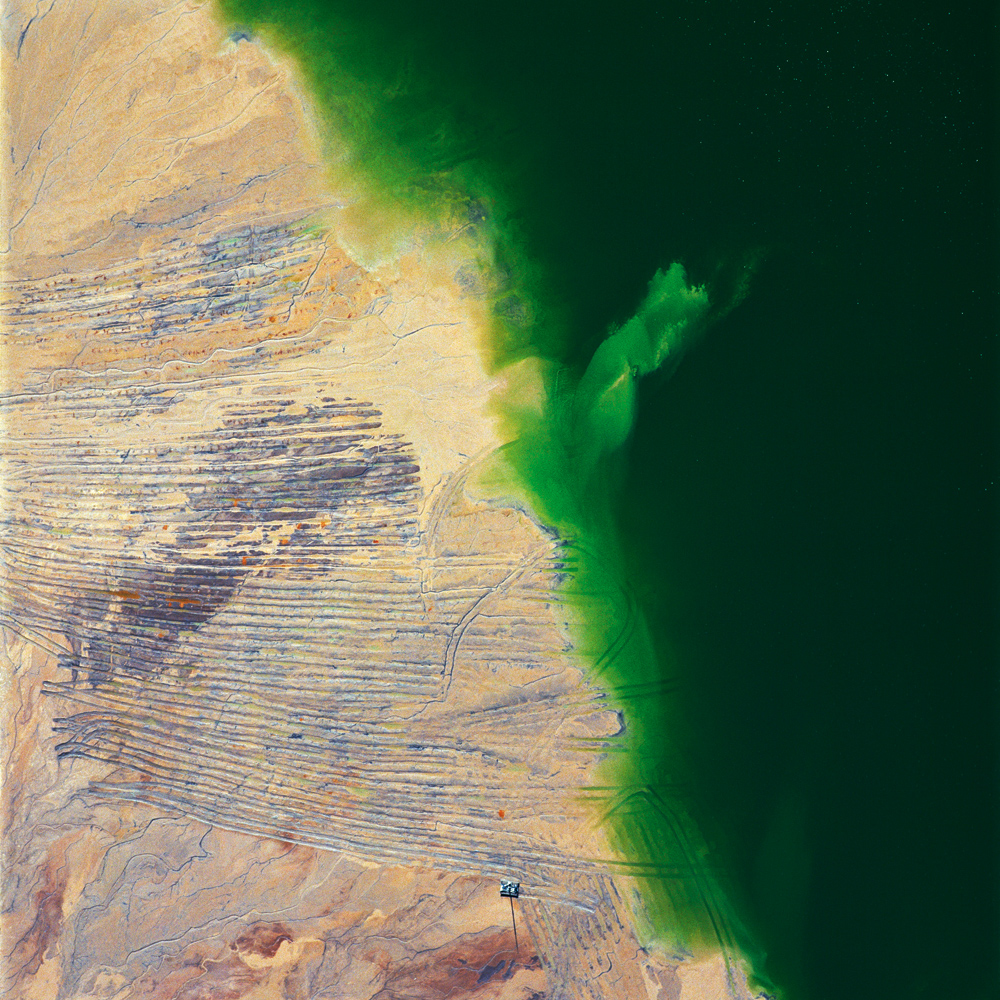

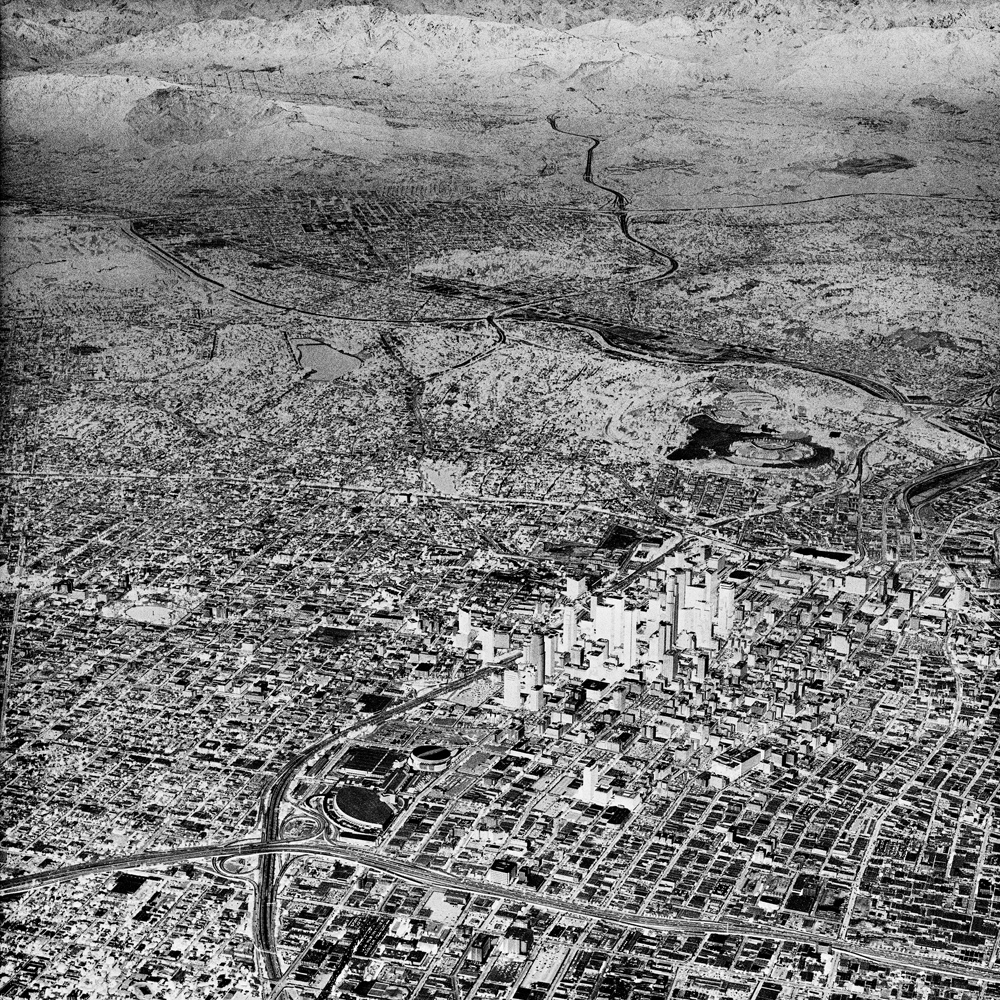

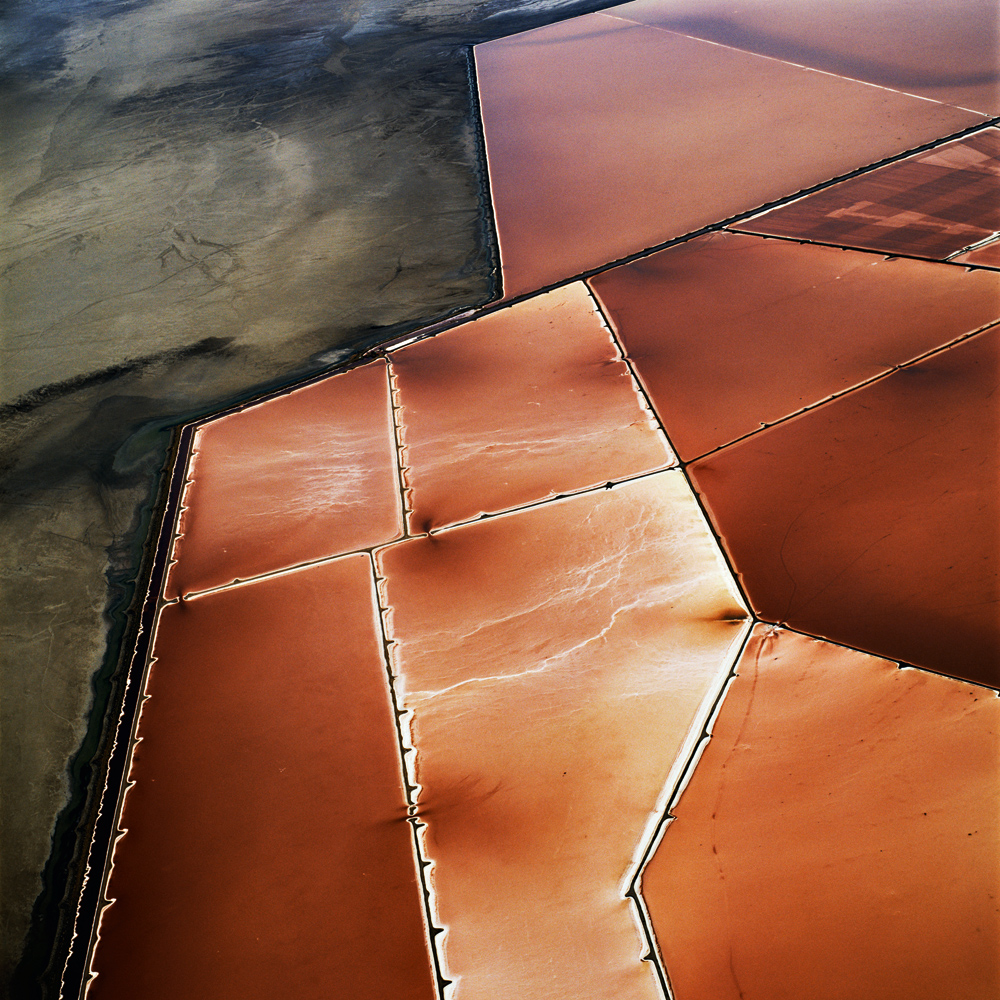

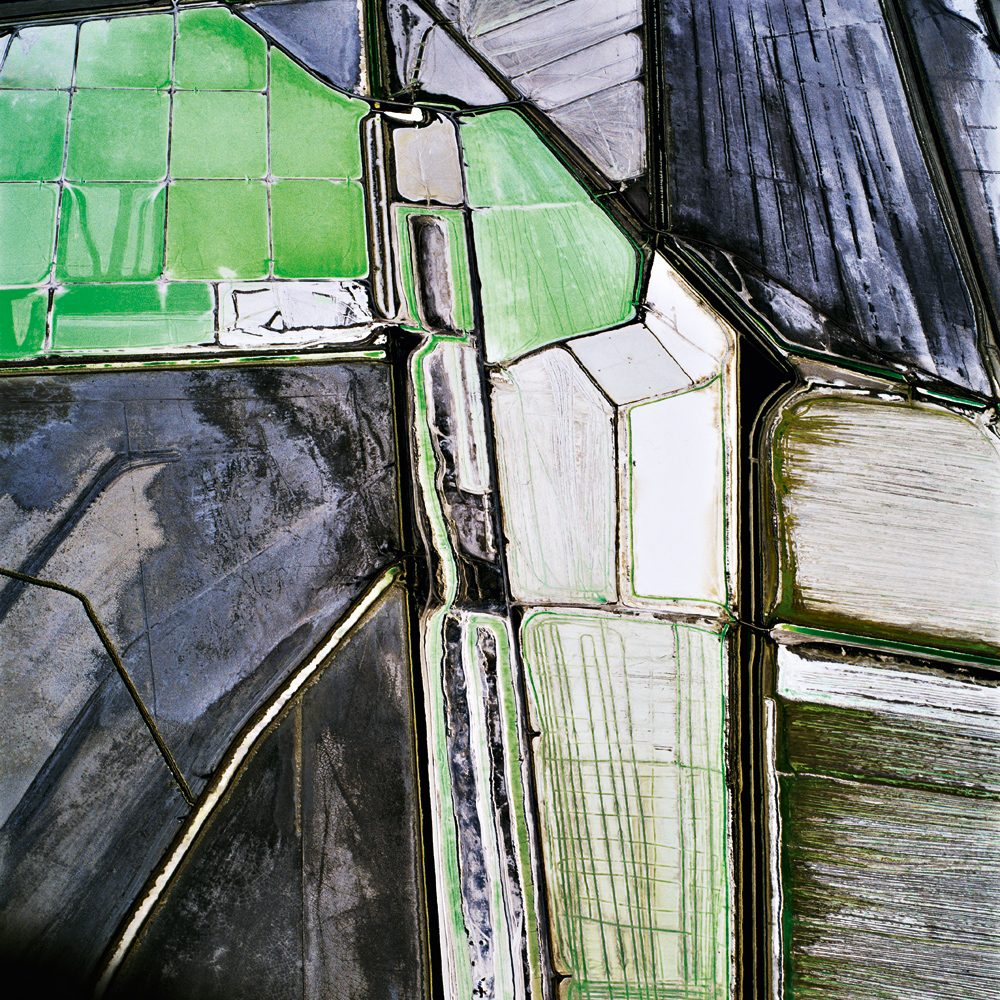

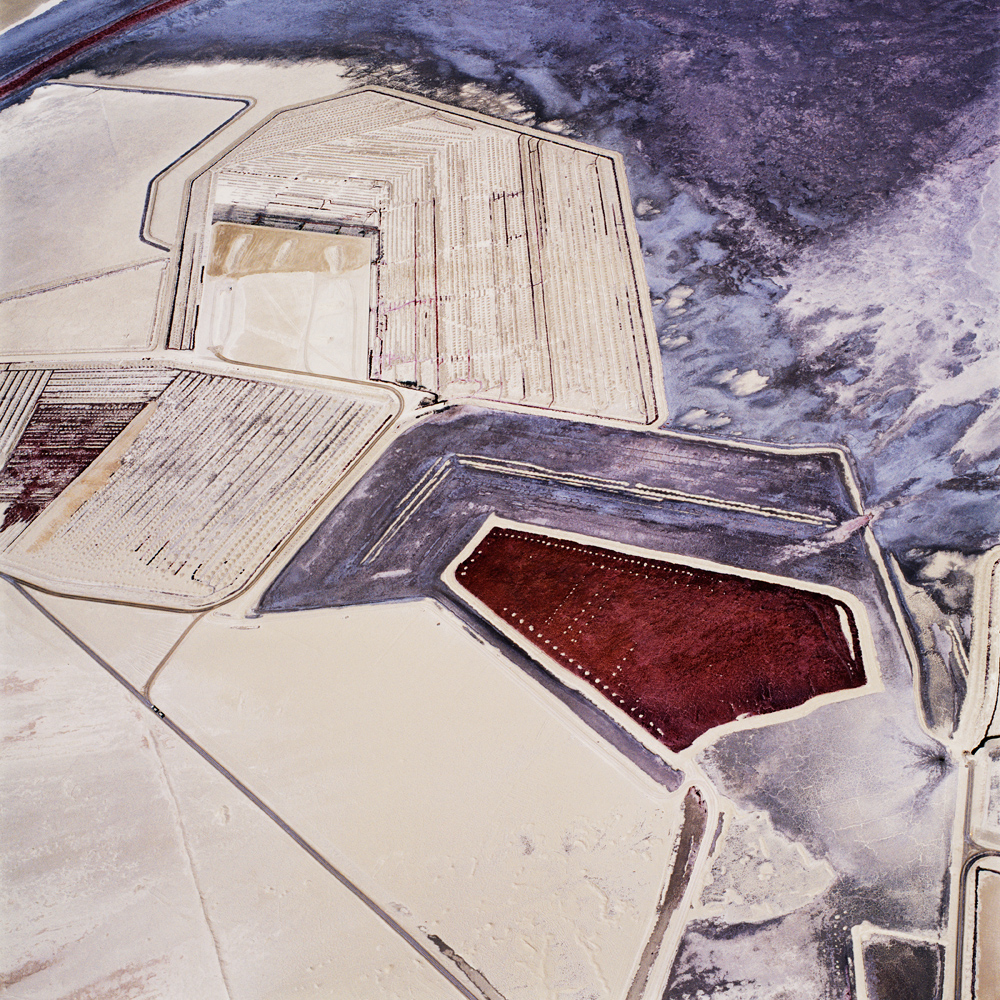

The work in Black Maps, unlike more polemic natural disaster photography, relies on abstraction. He creates full-frame surrealist visions of toxic lakes and captures the maddening designs of man-altered landscapes. In the abstract series The Lake Project (slide 15), viewers are overwhelmed by alien colors, allured by frame after frame of man-made destruction. The repetitive nature of viewing this destruction from a distance creates a sublime beauty in a classical sense. In less abstract work such as Oblivion (slide 7), which looks at the cityscapes of Los Angeles, the images become scorched black and white metaphors for the complete obliteration of a natural state.

Over the years, Maisel published a few of these projects as separate volumes, but in Black Maps, the intention is to see their power as part of a dialogue with each other. “I think the feeling of being kind of overwhelmed is almost part of the aesthetic of the work,” he says.

“There are just certain real conundrums on how we are developing the planet and changing the planet, and I think that’s what I still want to pursue,” says the photographer. But where Maisel could accuse, he instead becomes reflective on these issues, providing evidence of what he’s seeing and crafting in his printing process.

“I was also really conscious that these sites were American,” says Maisel. I was making a book about the country that I live in and that I know the best.”

He’s also keenly aware of the ethical contradictions of making photographic work in this way — with chemicals, computers and papers. “On that first excursion out West, I came back and I processed all my film and made my contact sheets and then I thought, ‘what the hell am I doing? How can I? — I can’t,’ I was paralyzed. And it took me a while to work through that, to realize that I’m embedded in this. At that moment in my life, I was living on the coast of Maine in this renovated barn that we heated with a wood stove, and it was about as far off the grid that I have ever gotten. I just realized I can’t remove myself from the society I live in and from my own way of wanting to communicate. But yes, I’m as guilty as the next person and I am complicit and I think that we all are complicit. This work isn’t meant to be a diatribe against a specific industry or industries.”

With that understanding of the interconnectedness of man and industry, and the conundrums involved in being a human in this era, Maisel’s work becomes a meditation on ourselves and what we’ve done to the planet. He say’s, “I think that these kind of sites correspond to something within our own psyches.”

“I think that … maybe these are all self-portraits. There’s something — we collectively as a society have made these places, that’s my take on it. And so, they really do reflect us. And so, it’s not ‘them’ making these places, it’s us.”

David Maisel is a photographer living near San Francisco and is represented by Institute.

Black Maps: American Landscape and the Apocalyptic Sublime is published this month by Steidl. The work is on view at the CU Art Museum, University of Colorado Boulder, February 1 – May 11, 2013, and will travel to the Scottsdale Museum of Contemporary Art, Scottsdale, Arizona, June 1 – September 1, 2013.

Paul Moakley is the Deputy Photo Editor at TIME. You can follow him on Twitter at @paulmoakley.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com