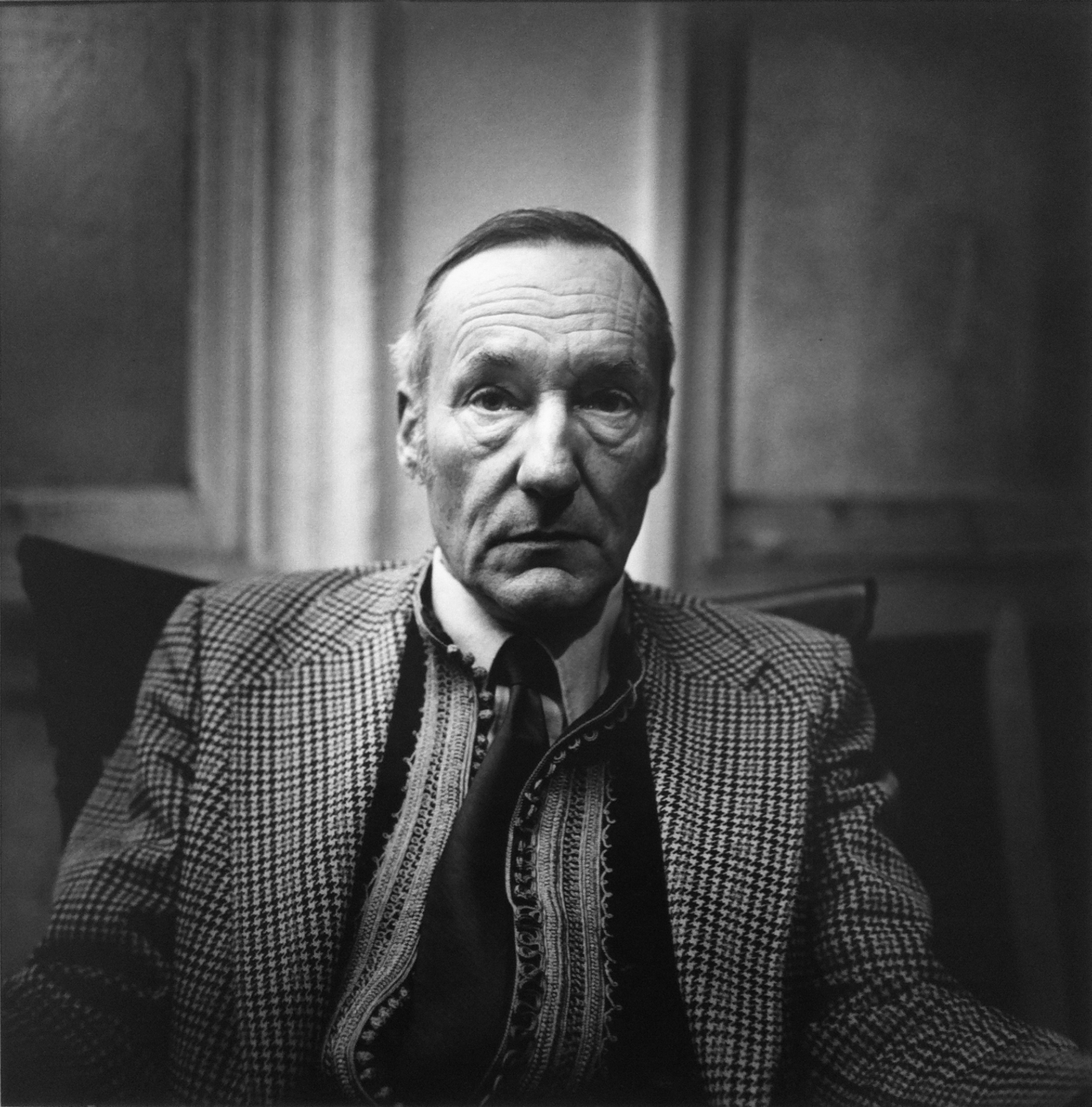

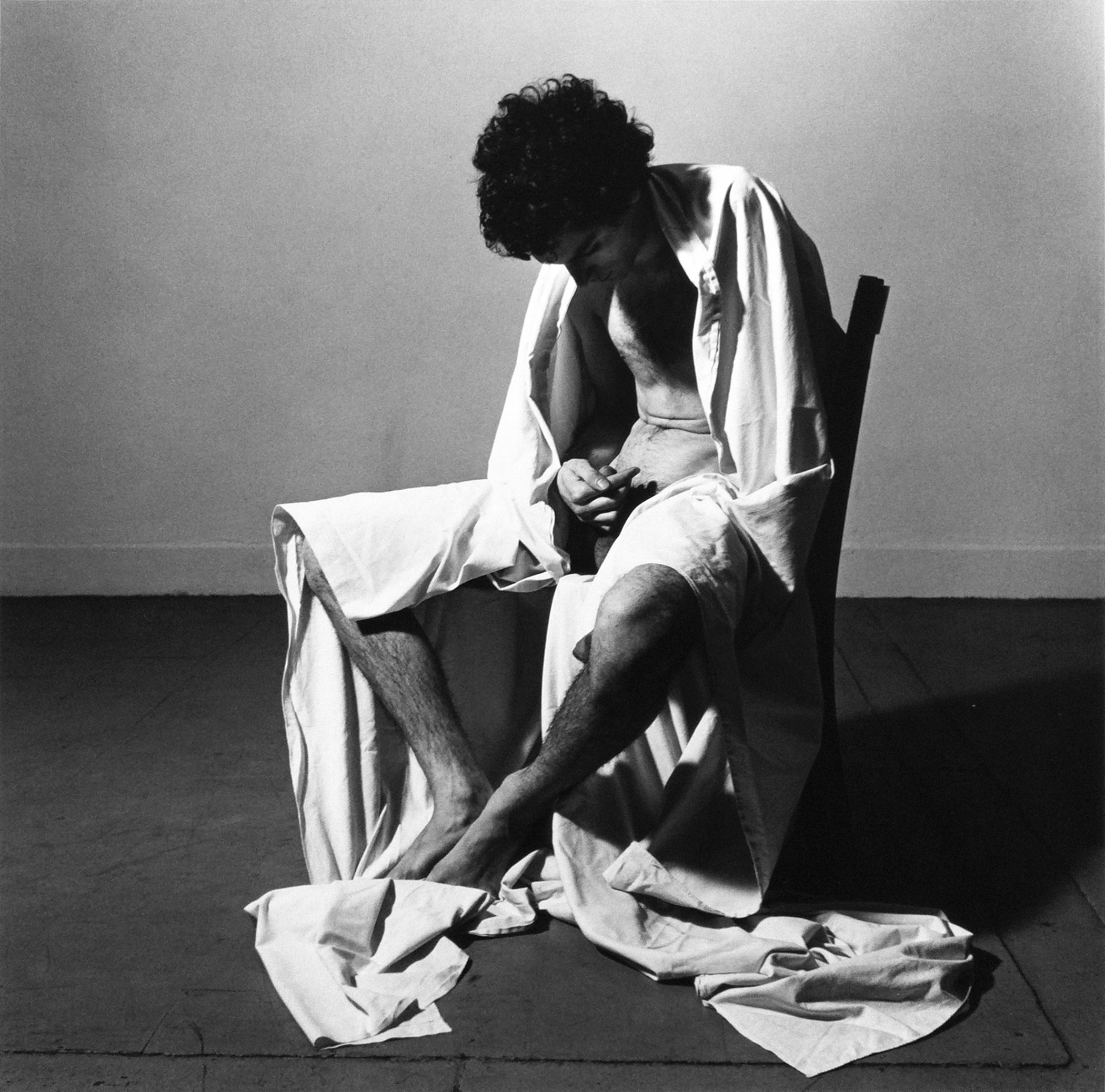

Peter Hujar’s work might be firmly rooted in time and place — the New York of the 1970s and 1980s — but it nonetheless has a timeless quality that goes beyond both. It’s not hard to see why: At his most elemental, he was a classical portrait photographer; one who despite choosing diverse, often shocking, subjects was relatively conservative with composition.

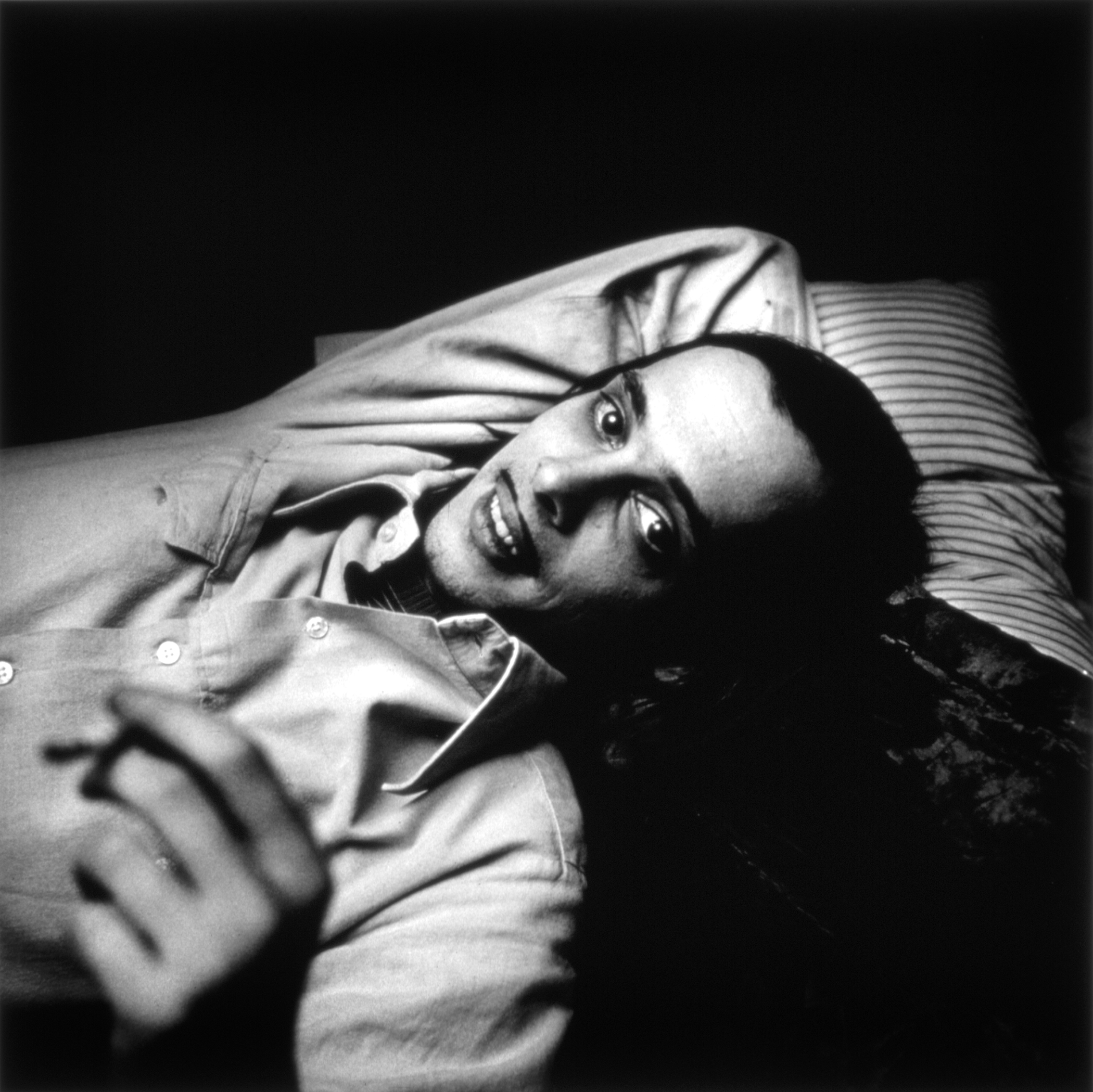

His most widely known pieces, a 1975 portrait of friend Susan Sontag lying on a bed and Candy Darling on her Deathbed – Darling, also a friend, was born James Lawrence Slattery and was part of Andy Warhol’s superstar set — exemplify this approach: Hujar gets us close to both, but we are never too intimate. As Sontag stares into the distance, and Darling beyond us, it is as if they are detached from their surroundings. And though posed, neither is performing.

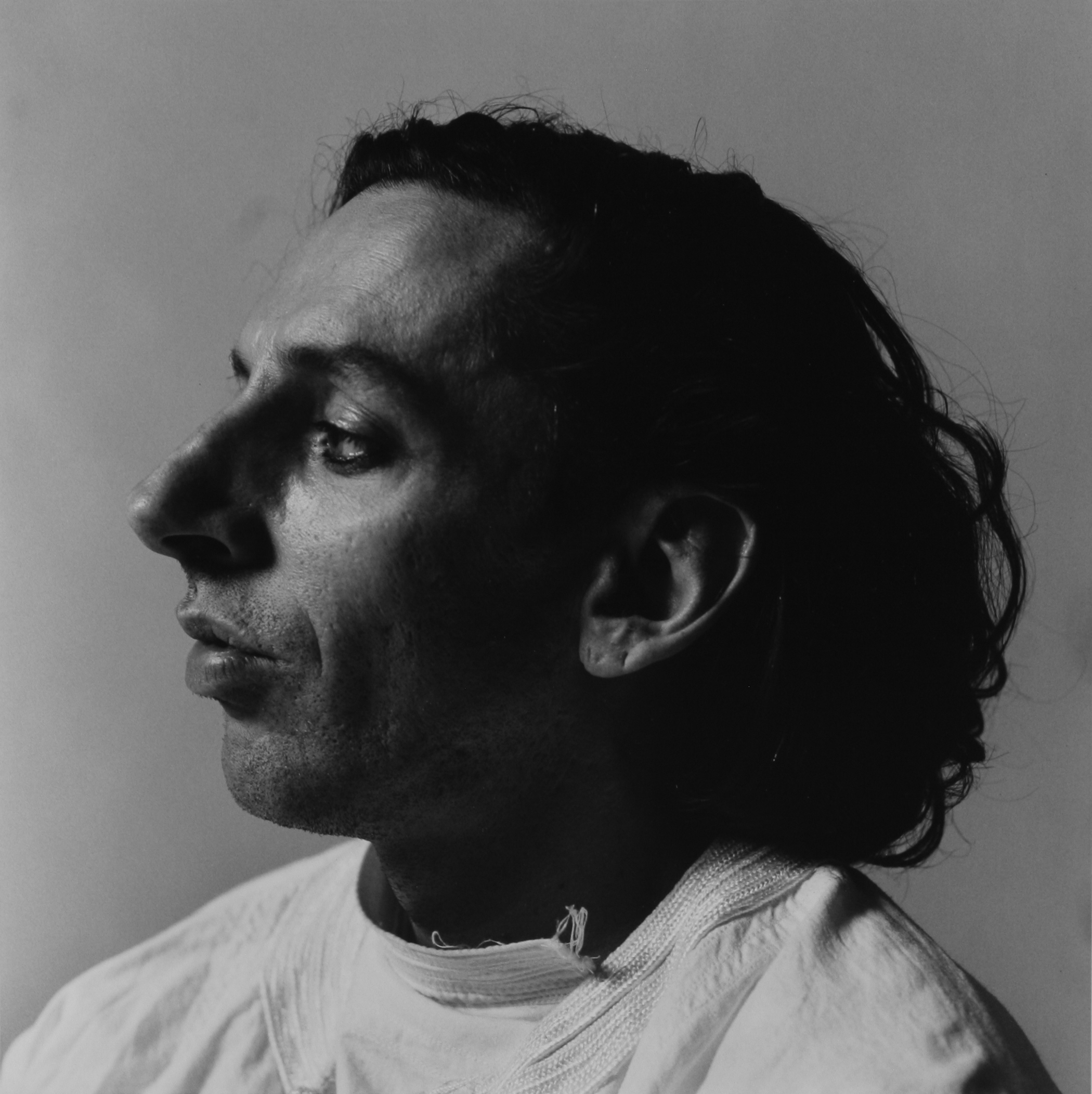

It is often said that death was not far from his lens. As a gay man living through the height of the AIDS crisis in New York, he was part of a community that came face to face with its own mortality. Indeed, the single book he published in his lifetime, Portraits in Life and Death, contains an introduction by Sontag where she says that photography “converts the whole world into a cemetery.”

Sadly, Hujar and his lover, artist David Wojnarowicz, were among the many people lost to the disease in the city (Hujar died in 1987, Wojnarowicz in 1992). Throughout their lives the two were often the subject of each other’s work. In a heartbreaking and poignant piece, Wojnarowicz famously photographed Hujar just after he died.

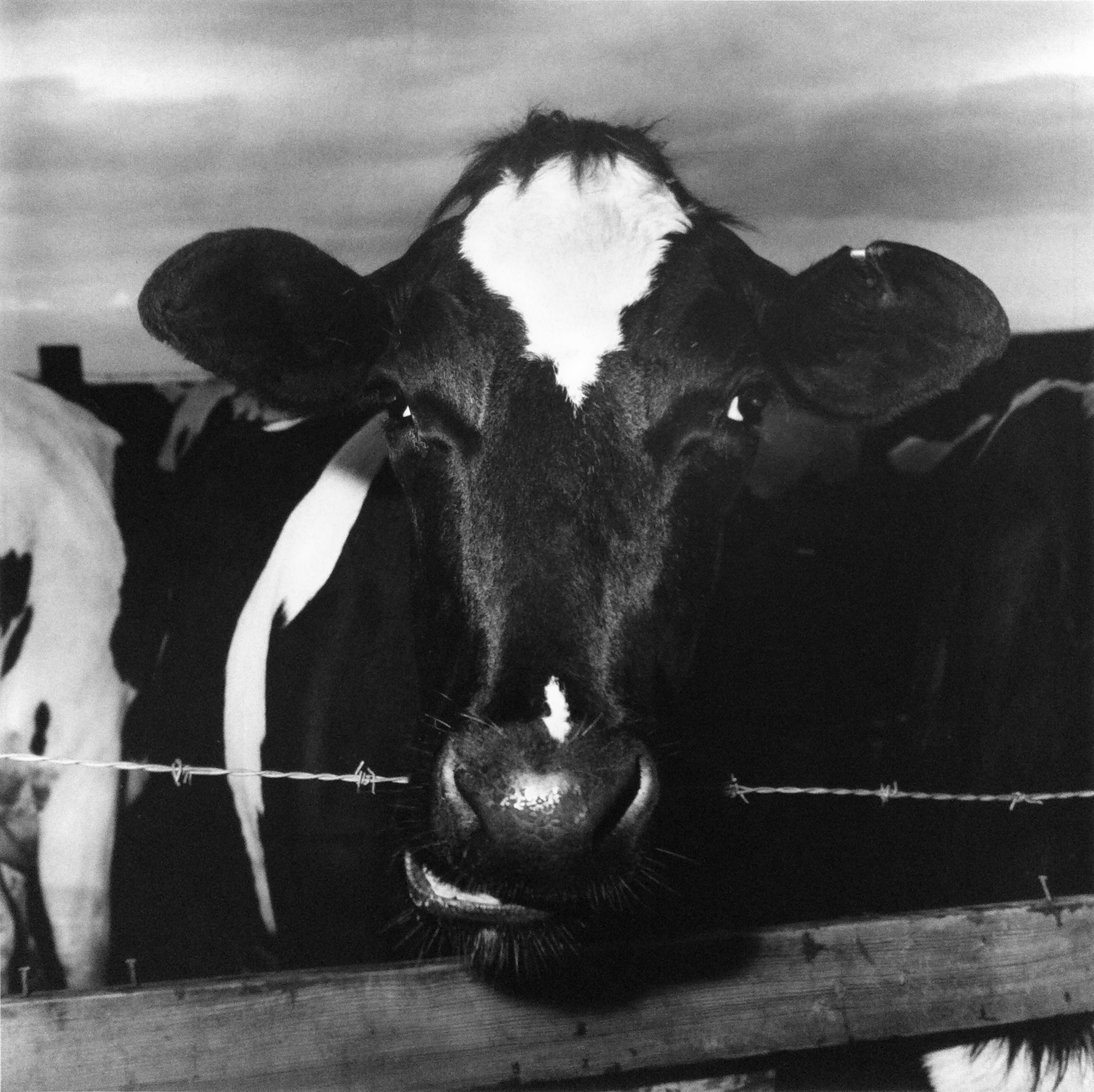

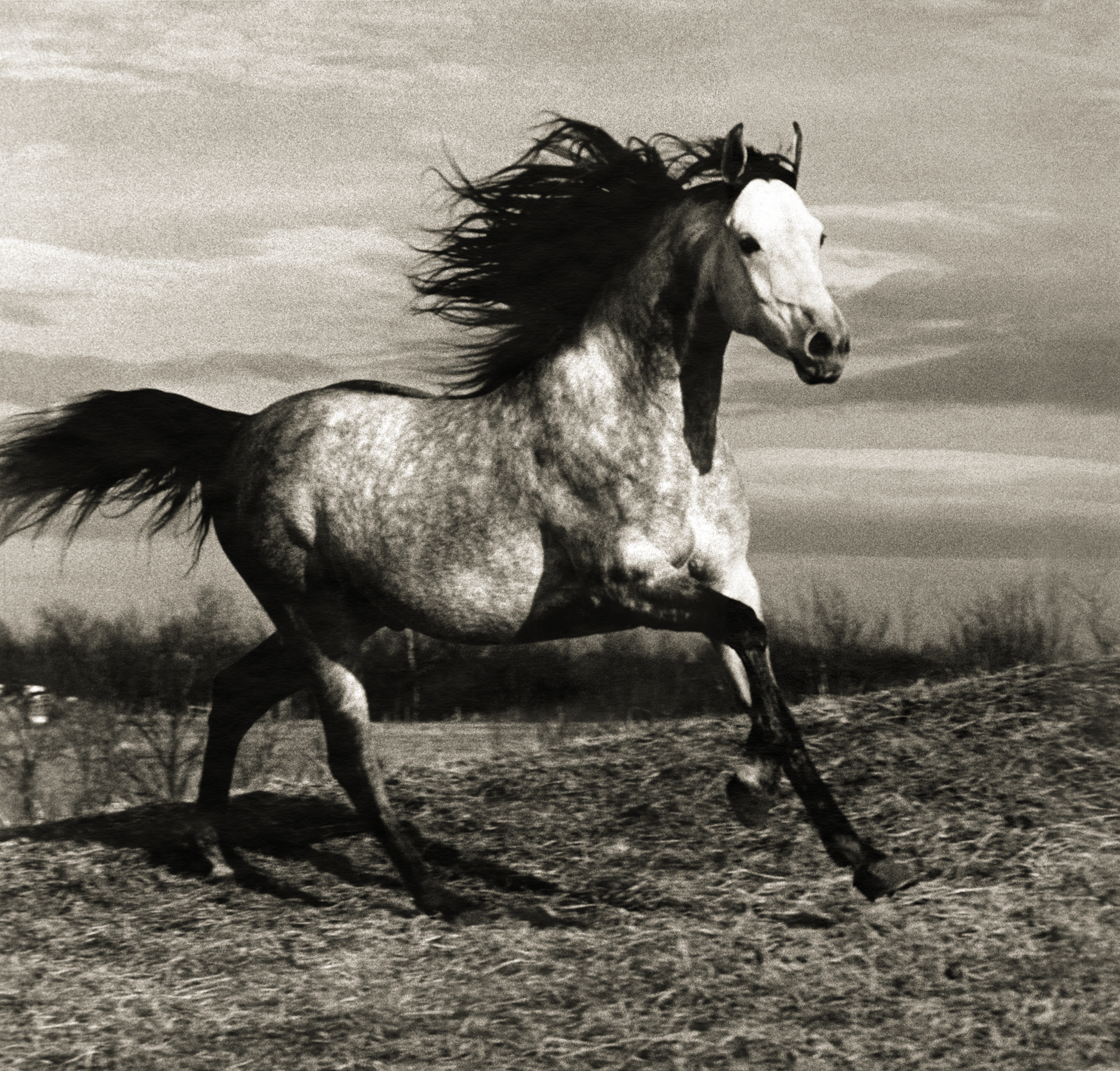

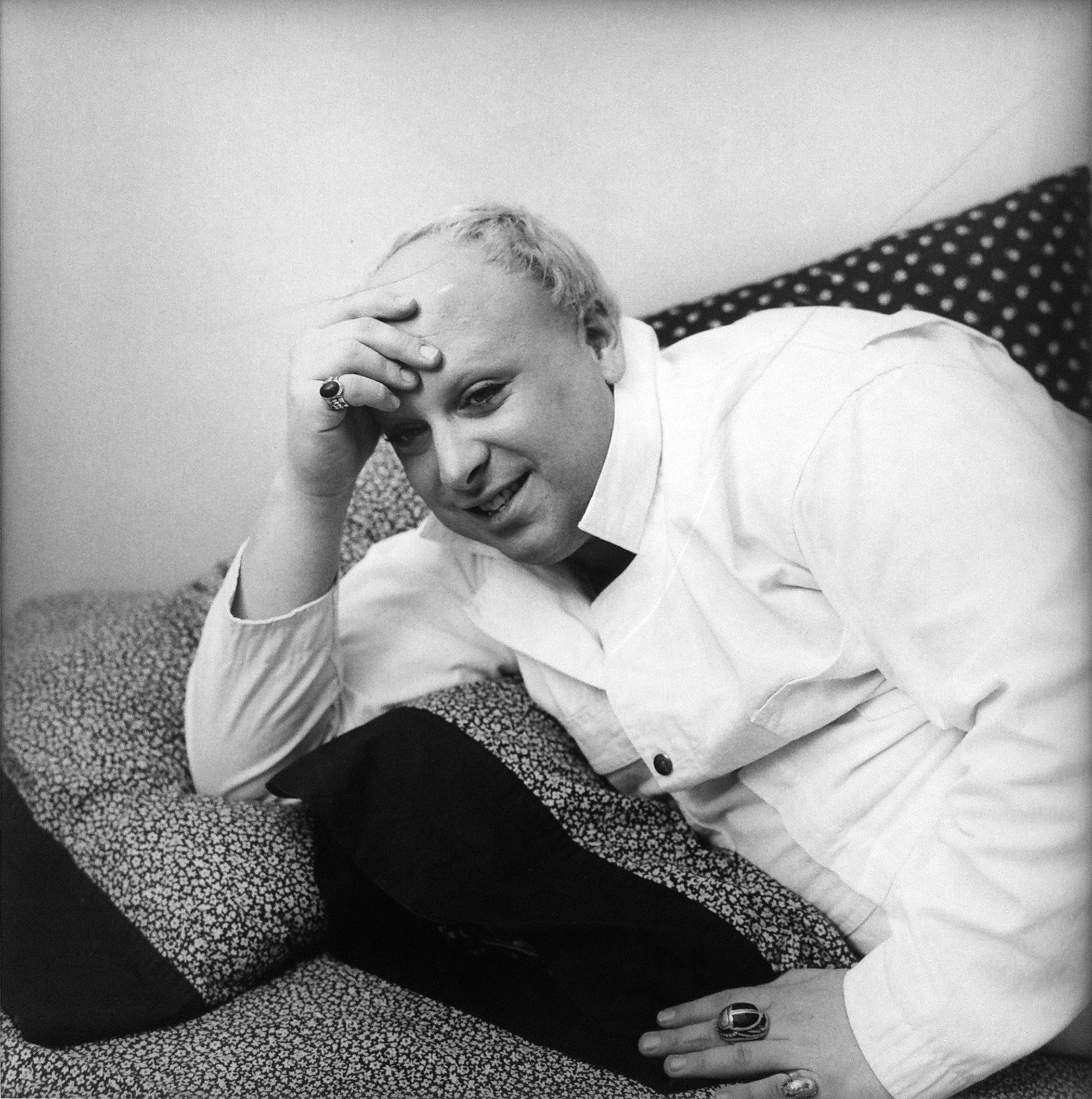

And yet an exhibition currently running at Pace/MacGill Gallery curates Hujar’s work in such a way as to allow a certain joy to emerge. His portraits of director John Waters and performer Divine are contemplative, even blissful, while Drag Queen with Curly Hair is as playful as it is candid. At the same time, Woolworth Building, Draped Male Nude and Running Horse are all strikingly beautiful in their own way, and show us how his careful formalism allowed him to revel in any subject.

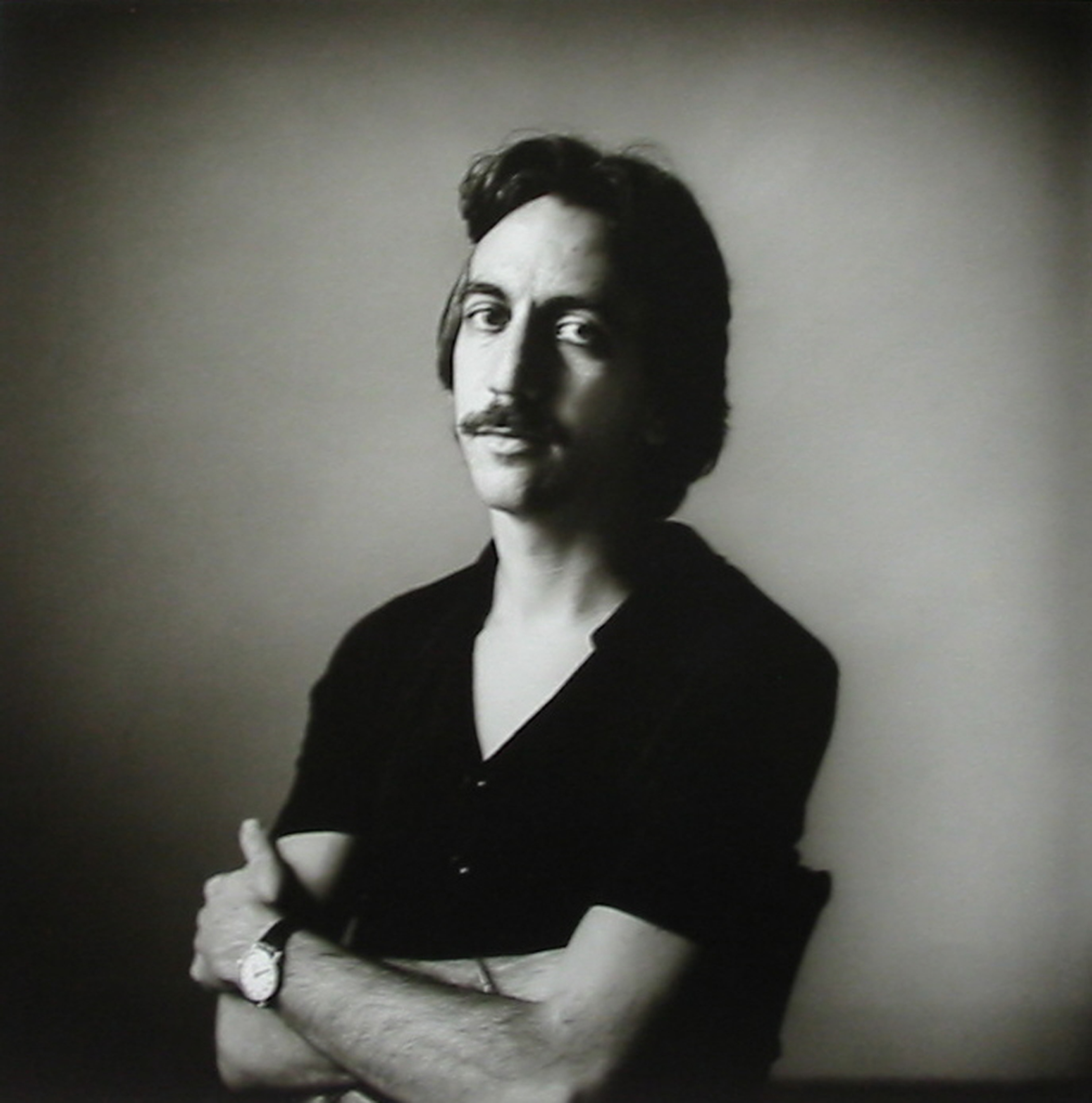

Vince Aletti – photography critic with The New Yorker — was a friend of Hujar, and the subject of a 1975 portrait included in the show. Aletti tells TIME that he remembers Hujar as an often quiet, friendly photographer while in studio — one dedicated to the task. The key to much of Hujar’s photographic success? His relationship with subjects: “there was an intimacy,” Aletti adds.

Others argue that he was not technically as gifted as his contemporaries and those he influenced – Robert Mapplethorpe and Nan Goldin, for example. And though he never quite made it into the public consciousness as they did, it is wonderful to see that he has since gained steady recognition as one of the most important artists of his generation.

The exhibition Peter Hujar runs at Pace/MacGill until April 20, 2013

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com