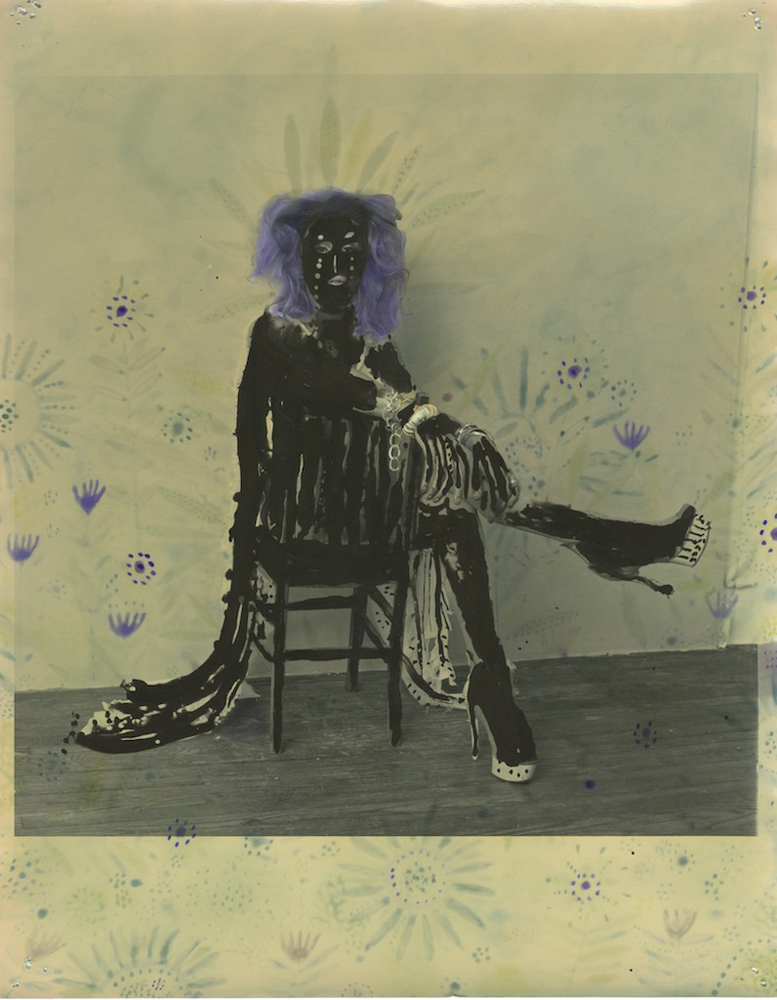

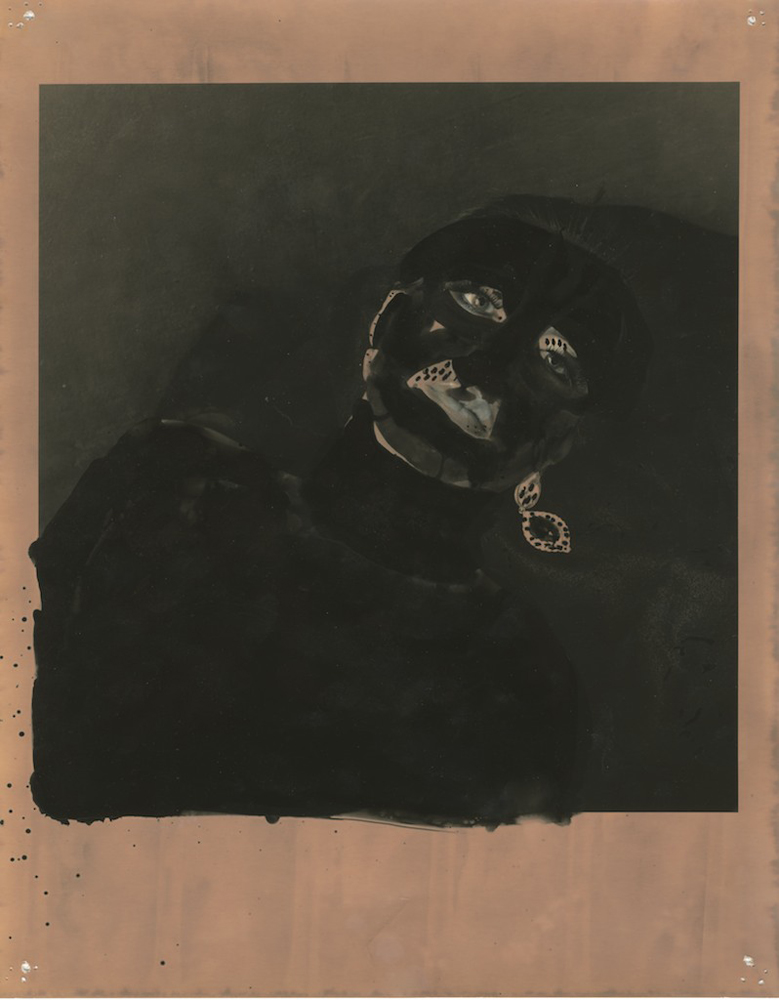

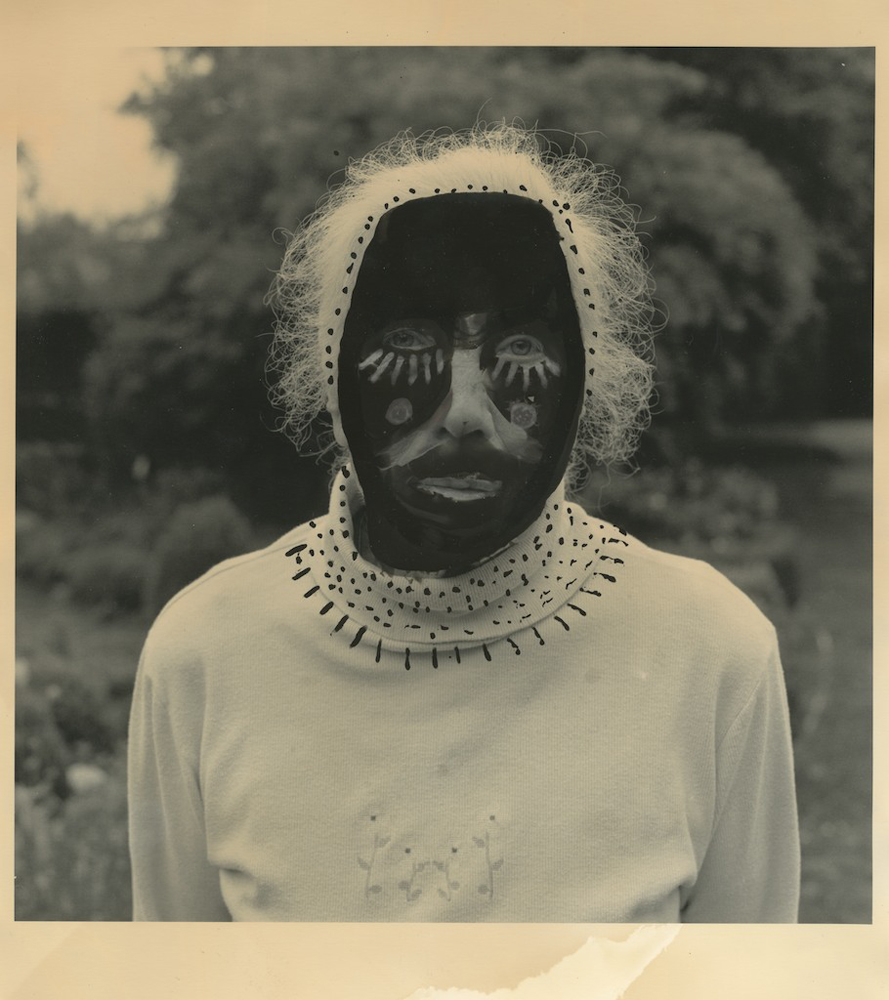

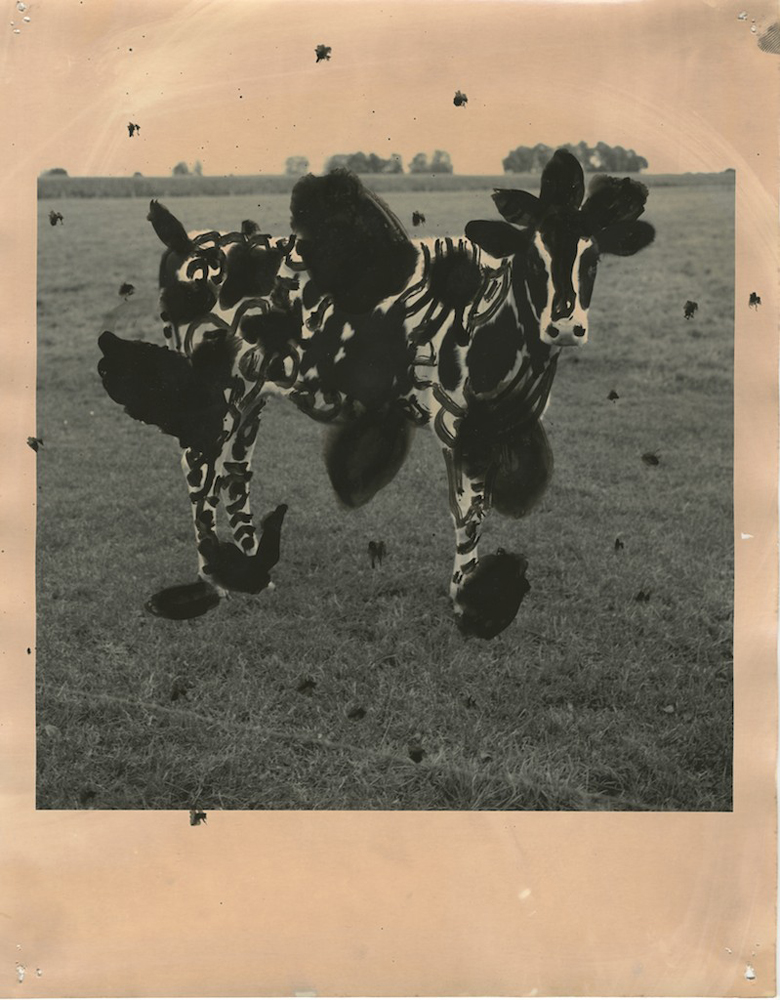

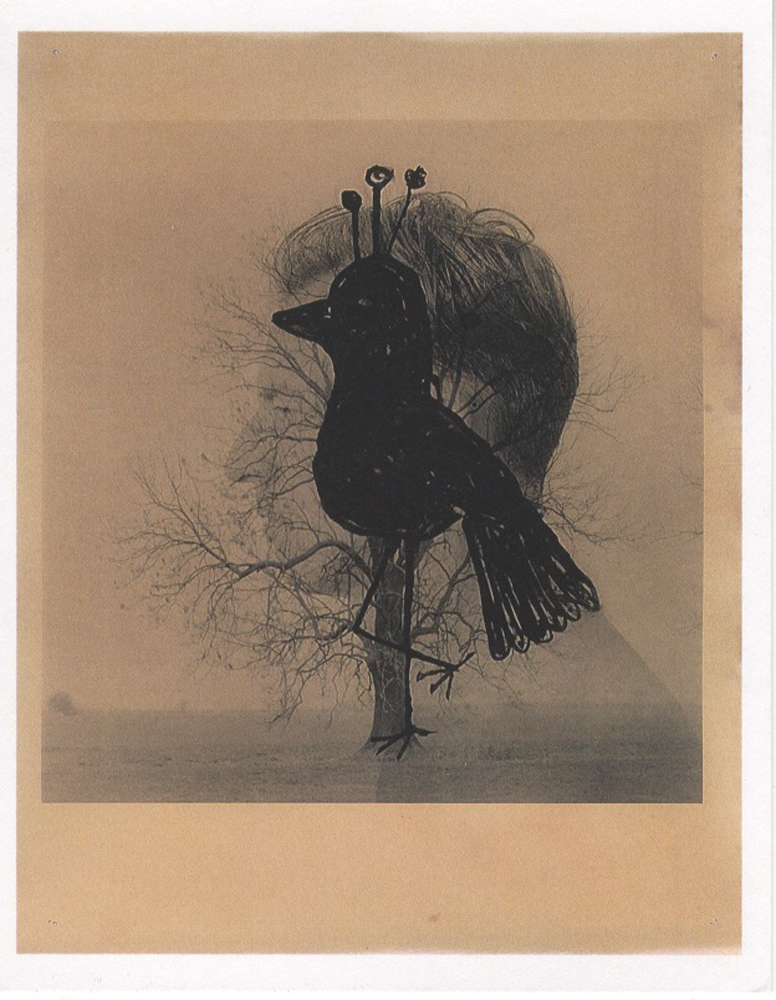

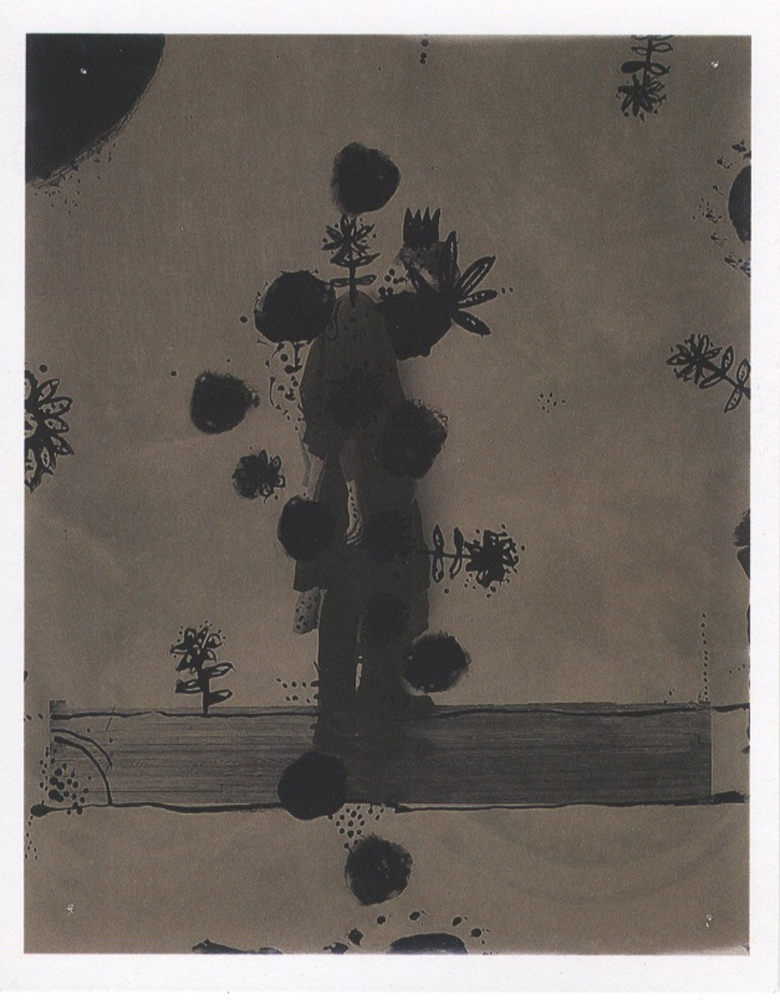

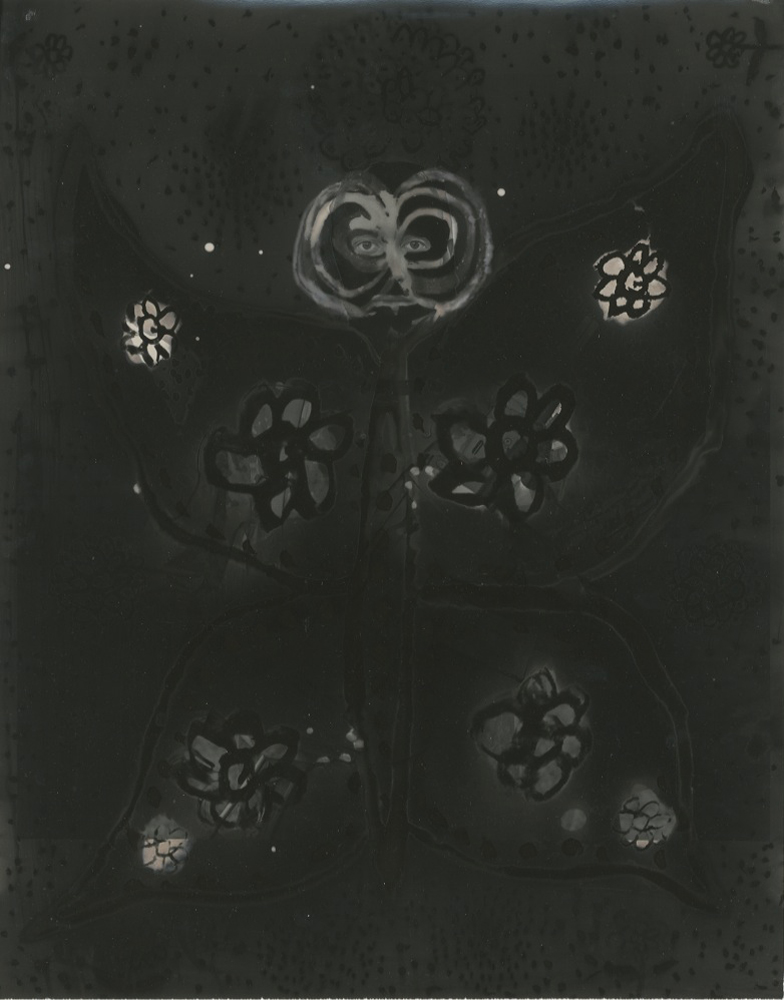

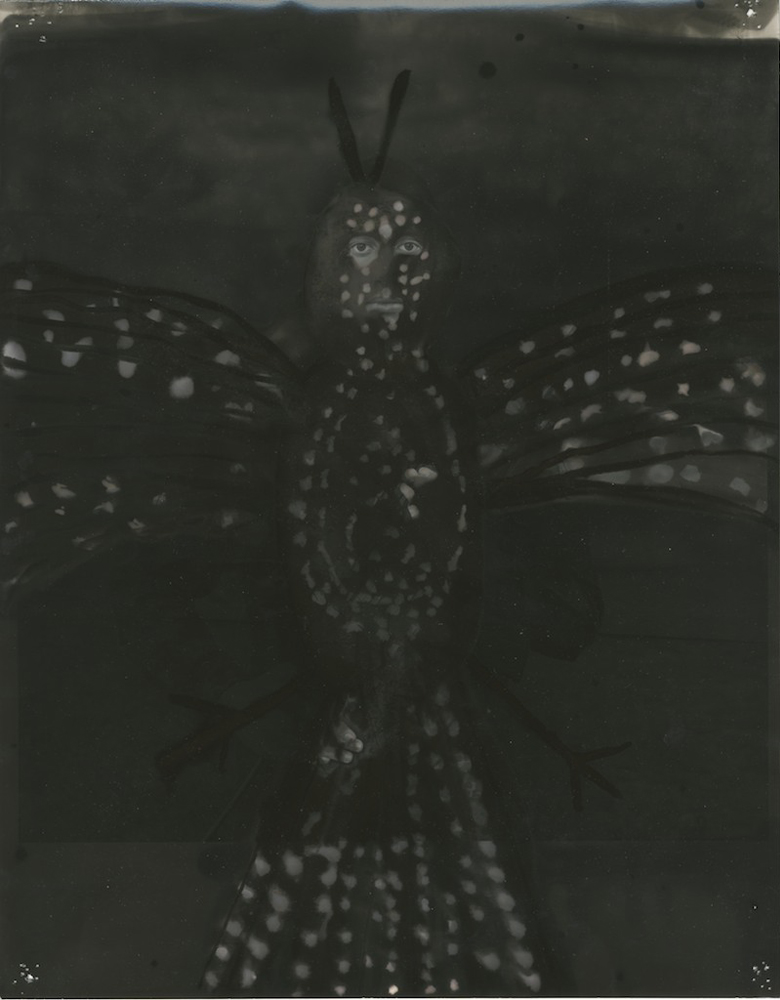

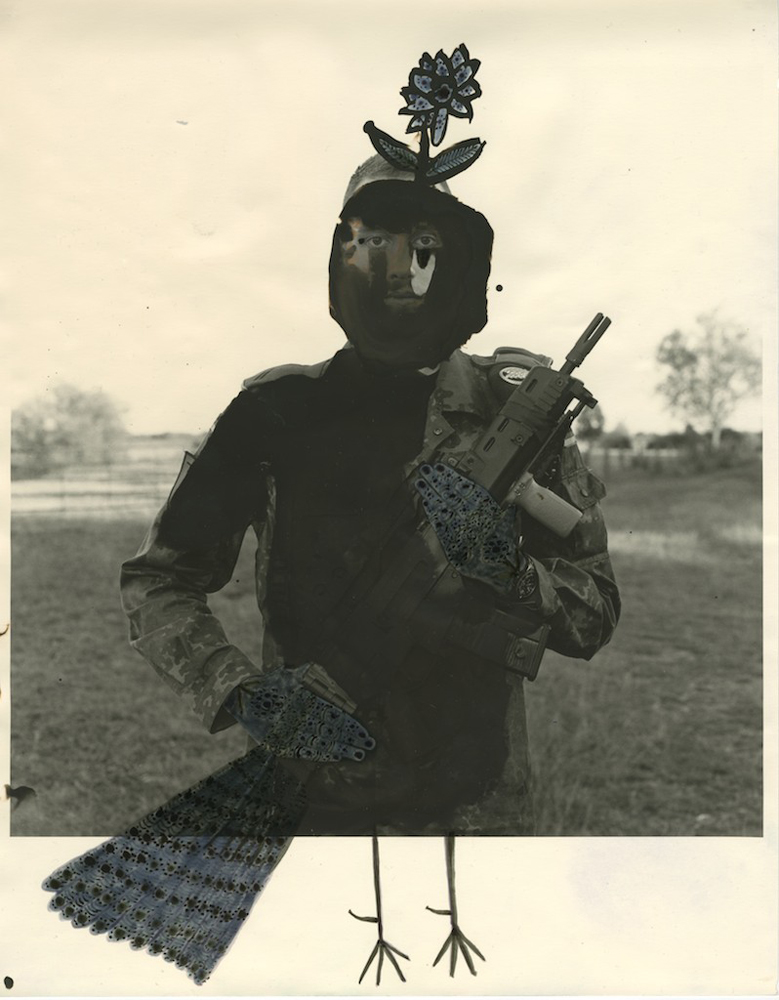

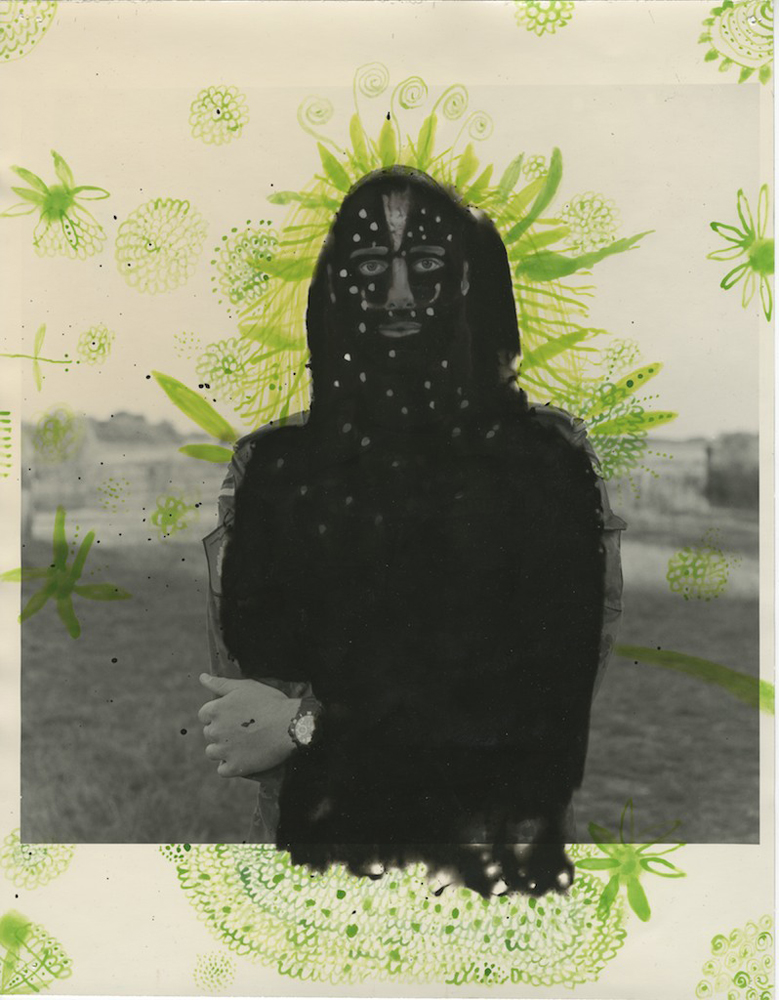

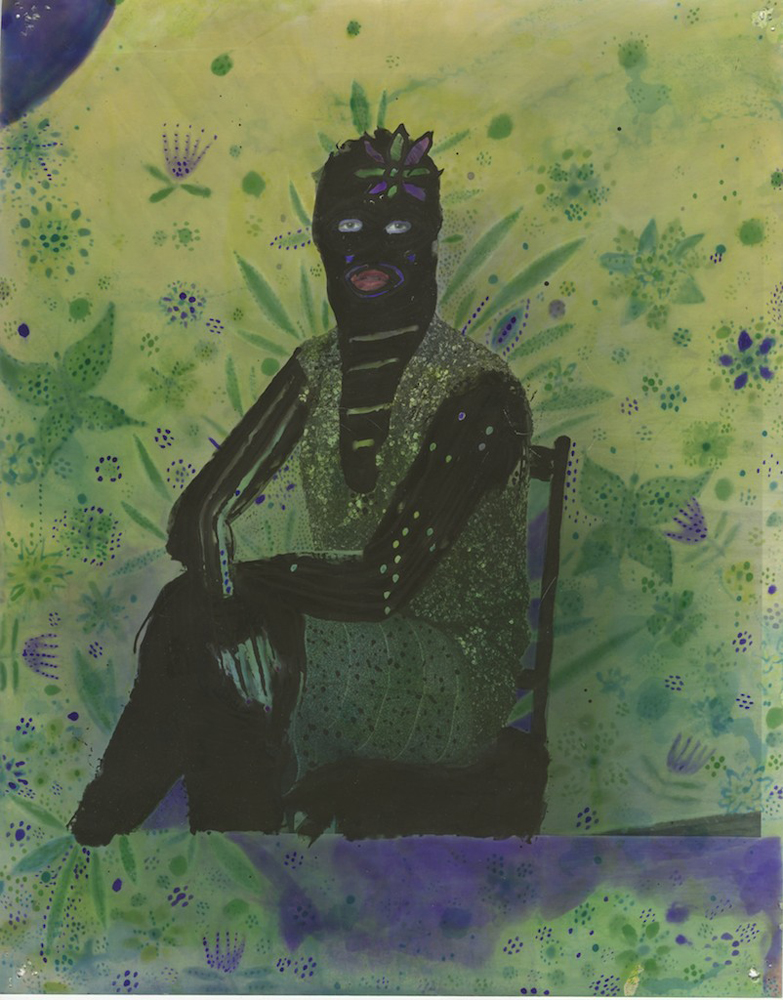

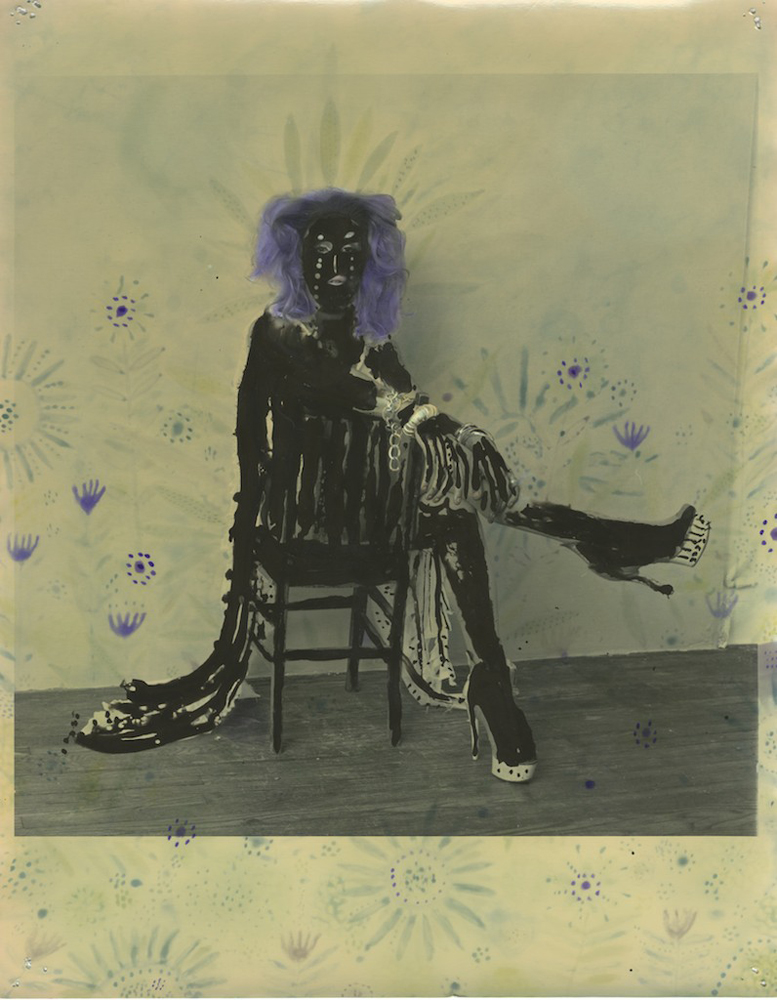

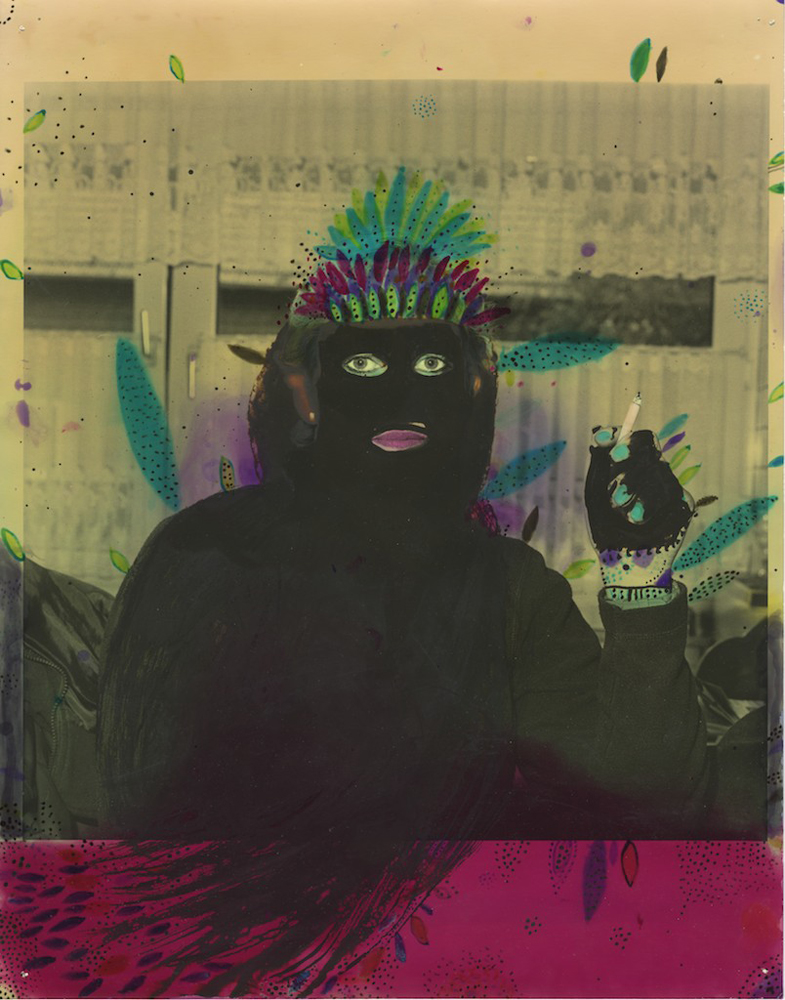

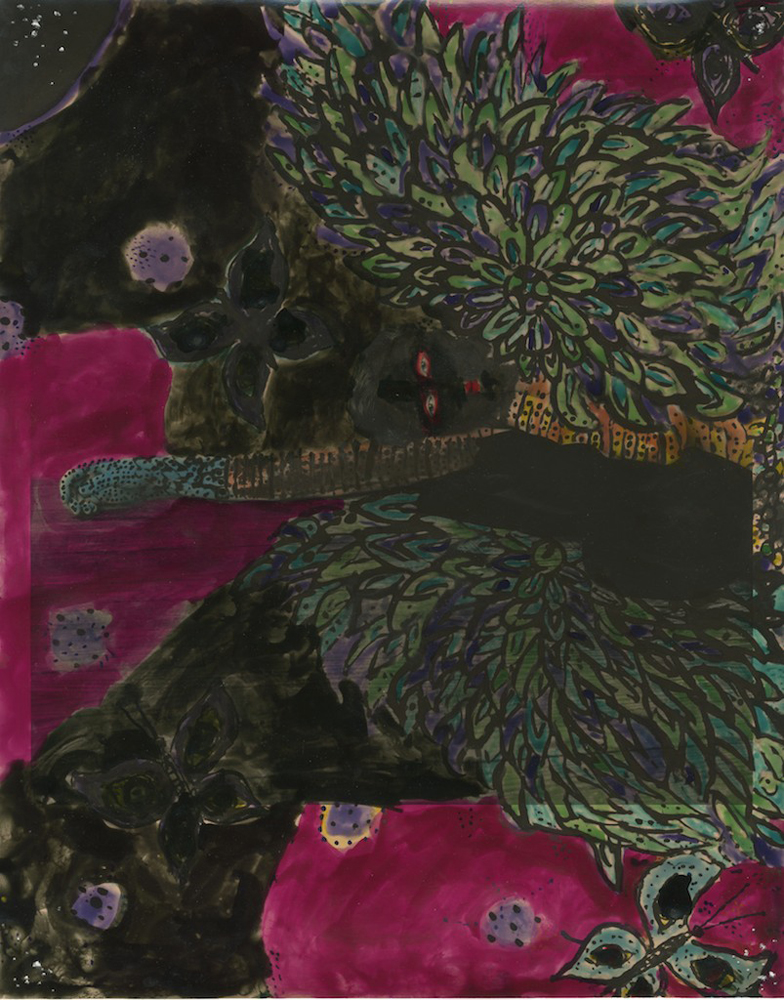

It’s rare to encounter a body of work as wholly original as Dietmar Busse’s extraordinary series, Fauna and Flora. An amalgamation of photography and painting, the pieces in the series manifest a beauty that occasionally veers into dark, dreamlike realms.

Busse, 46, grew up as an only child on a small farm in Northern Germany and traveled widely in Europe and Morocco as a teenager before settling in Madrid, where he became interested in photography.

“Making art for me is like being on the road, except that the [artistic] journey is an inward one,” he recently told TIME. The work in Fauna and Flora, meanwhile, mirrors that travelers’ sensibility, emerging from a process Busse describes — like a road trip — as “full of surprises and spontaneous decisions.”

In 1991 Busse relocated to New York, working initially as a studio assistant. By 1995 he was receiving commissions as a fashion photographer for magazines like Paper, Interview and Visionaire and portraiture for the New York Times Magazine, Harpers Bazaar and more.

He soon became disillusioned, however, with the constraints imposed when working for others.

“I had always secretly hoped to become an artist,” he says, “so I attempted to free myself from any outside demands.”

He withdrew from the world of commissioned photography to pursue his artist’s vocation. In 2006 he began inviting people he found visually interesting — people in art and fashion, for the most part — to visit his Manhattan apartment, converted into a little studio, to have their portraits taken for a project he calls Visitors. The result: an impressive portfolio of black and white portraits.

“I like having people over, rather than going on location. The sitter enters my world, and that way it is so much easier for me to get to know them and for them to relax.”

The one exception to this comfortable, intimate approach has been annual visits to his native village in Germany where, for years, Busse has photographed residents, animals, landscapes and, until recently, his stepfather, Fiddy, a constant companion on those month-long explorations of his homeland.

“My father was very good with the local people and always made sure that I had access to anywhere and anyone I wanted. We were like little kids, up to no good and we had so much fun.”

In March 2012 Fiddy was diagnosed with cancer; he died within a month of the diagnosis. Busse spent almost the entire year with his mom — driving, shooting and continuing the project in Fiddy’s honor.

“He came into our lives when I was ten years old,” Busse says of his stepfather, “and rescued me and my mother from an impossible situation. He was like an angel to us. We miss him terribly.”

Today Busse remains very much in the analog world, shooting film and making his own darkroom prints — a hands-on process that helped release him from the constraints of traditional picture-making.

“About six years ago,” he recalls, “I made a ‘mistake’ in the darkroom and double-exposed some paper. I pursued these double and triple exposures, mixing images from my homeland with portraits of people in New York. I liked bringing these two worlds together.”

Busse began painting (with photographic developer) on his prints. The resulting images so artfully meld the otherwise quite distinct media that they appear to coalesce — creating, in a sense, a new medium.

“There are all kinds of variables when you draw on the prints before they are fixed, and it’s a relief not to worry about spots or imperfect exposures anymore. I embrace the ‘accidents’, the unforeseen, the spontaneous. I never quite know where things will lead me: it’s like an expedition into unknown territory. There is a lot more freedom there, and that is more reflective of who I am as a person than trying for a perfect print.”

With no formal art training, Busse was long intimidated by the idea of painting. But in the last few years he began extending his experimentation even further, applying photographic retouching colors and inks to his prints.

“Having a strong foundation in photography,” he says, “somehow gives me the courage to explore. The photograph serves as the foundation for the painting, capturing something about a person’s energy and spirit the way only photography can. The painting starts where photography can not go.” It is these co-mingled pieces that comprise Fauna and Flora.

“I did not set out to [focus on those concepts]. These were just the images I found myself making — and it made sense, for fauna and flora are what I grew up with, and what I relate to.”

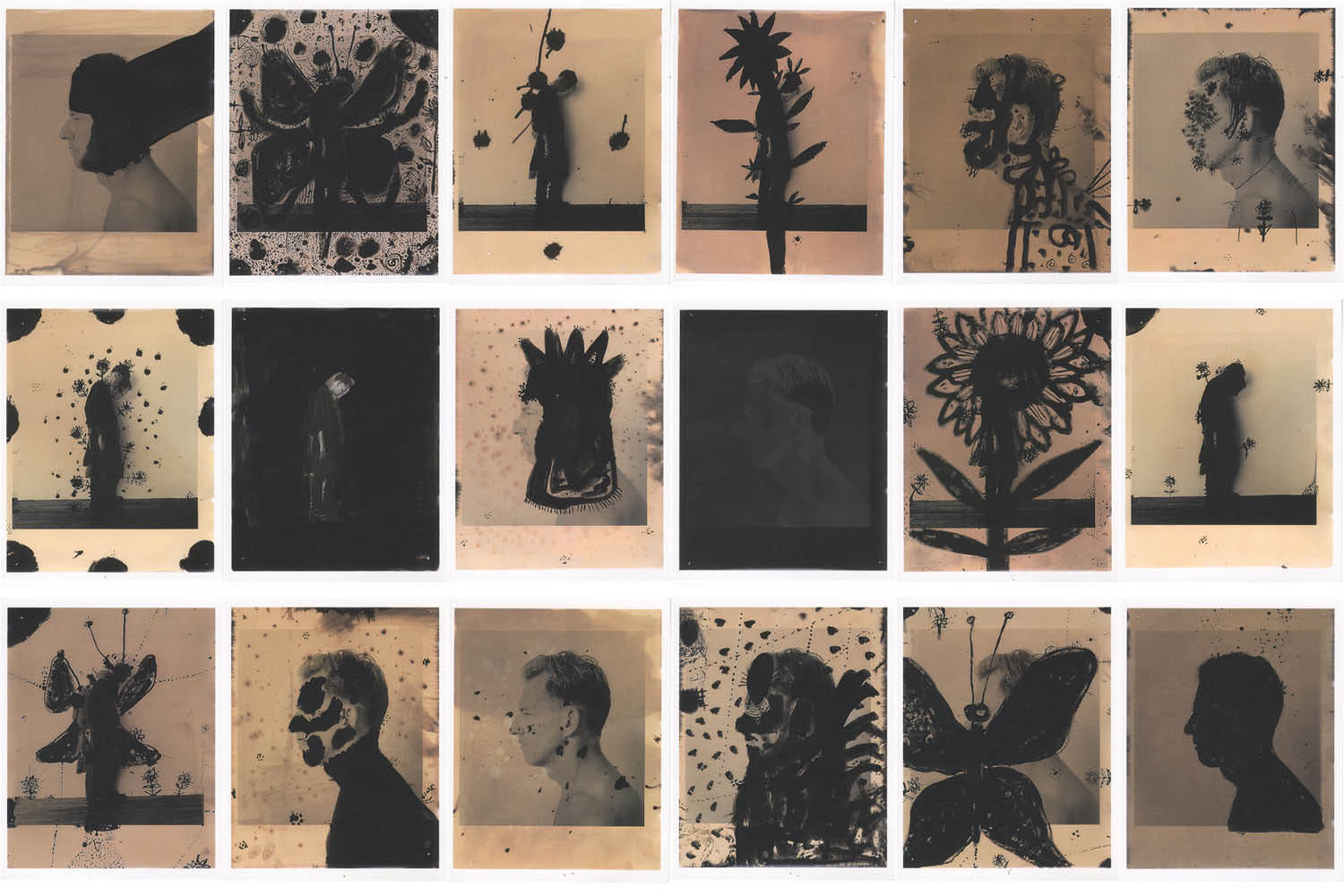

Two years ago Busse’s friend, the collector Scott Newkirk, commissioned him to make a portrait and also requested that Busse integrate his painting process into the images. “I was insecure about the drawings so I did forty pieces in three days, [thinking] he would maybe like two or three and buy them. I hung all forty up together and it was a completely new way for me to look at my work.”

Newkirk ended up with a 20-piece installation, and Busse with a new methodology. “With twenty variants on two images, there is repetition of the same image throughout the installation as well as a uniqueness about each piece. The installation becomes one big story and the viewer is invited to go on a journey and explore.”

Busse is currently working on another installation, Soldier, Soldier, which combines many of his experimental processes.

“I don’t feel like I have completely resolved it, but [the series] is on my studio wall right now. I’m just looking at it before I make the next move.

Dietmar Busse is a German photographer based in New York.

Phil Bicker is a senior photo editor at TIME and TIME.com.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How the Economy is Doing in the Swing States

- Democrats Believe This Might Be An Abortion Election

- Our Guide to Voting in the 2024 Election

- Mel Robbins Will Make You Do It

- Why Vinegar Is So Good for You

- You Don’t Have to Dread the End of Daylight Saving

- The 20 Best Halloween TV Episodes of All Time

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Contact us at letters@time.com