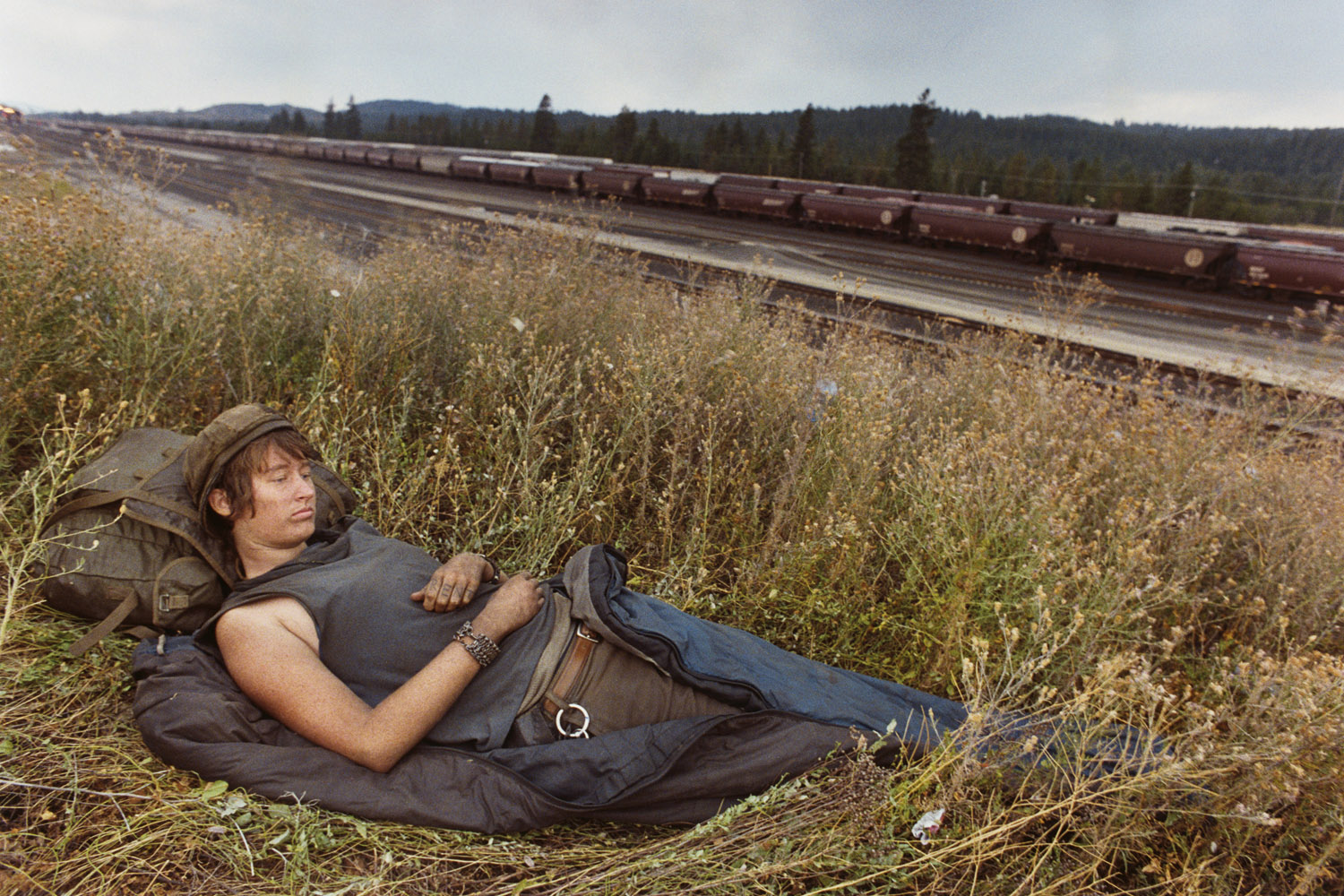

Mike Brodie is easy to mythologize. A teenager-turned-supertramp (a term usually used to describe youth eager to travel by whatever means and for as little money as possible) Brodie became a darling of the photography world after carting an old Polaroid SX-70 and some stale bagels on his first train-hopping experience across the United States.

Equal parts anthropologist, documentarian, and punk, Brodie turned his borrowed camera on the rarely seen community of rail-riders and earned the monicker, Polaroid Kidd —a name he’d often scrawl (or “tag”) on box cars or bare walls.

Starting in 2004, at age 17, Brodie rode the rails year after year, logging more than 50,000 miles and traversing 46 states. He would eventually switch from Polaroid to traditional 35-mm film, but Brodie continued to document the lives of squatters, hobos, and the country’s youth in search of adventure. What struck many critics was the spirit of his photography —unfiltered and without a pedigree in the field, Brodie simply enjoyed taking photographs.

“I just took photos of my life,” he told The New Yorker this January.

About the intimacy of his work, he pushed against photography further. “I would have gotten a lot closer without the camera in my face.”

By 2008, the work was being critically acclaimed, making rounds at places like PDN and The New Yorker, and earned Brodie the 2008 Baum Award for American Emerging Artist. At the time of the award, however, Brodie had largely disappeared. Some said he’d given up photography, others believed he was off working on the next project. Silence only inspired further questions.

Brodie would surface occasionally over the next few years. In late 2008, he spoke with the Pensacola Independent about his award and life. In 2011, he spoke with Fader Magazine about what it was like to ride the rails. There he said it wasn’t the photography that kept him on the road, it was the adventure, the world ‘out there.’

“I had a lot of curiosity about the world and wanted to go travel. It was an addiction,” he told Fader. “Photography turned out to be something that just happened naturally for me.”

While it may have happened naturally, photography was never his passion, he said. In the article, Brodie shared a short-list of personal goals; photography didn’t make it. What did, however, is particularly telling of Brodie’s character:

Pay off all debts to society;

work ten years with the railroad;

get a bachelor’s degree in mechanical engineering;

establish a 401K;

buy a truck;

and have a kid

Today, Brodie has a degree in diesel mechanics from Nashville’s Auto Diesel College, one step closer to his goal of working for the railroad, and is employed as a mechanic in Oakland, California. Unlike many of his colleagues, though, Brodie will mark 2013 with the release of his first book of photographs, “A Period of Juvenile Prosperity” — a book of compiled photographs that Brodie said “also documents a period of transition in [his] life — just after puberty and just before manhood.”

With two galleries, Yossi Milo in New York and M + B G in Los Angeles, slated to show his work this March, Brodie might not accept the label of photographer, but his work has struck a chord with audiences in this world.

Brodie’s images have been described as having a “distinct style and authentic voice within the lexicon of photographic history that is so uniquely his own, while simultaneously characteristically American.”

Through it all, though, Brodie’s actual voice remains silent (LightBox’s attempts to reach the artist for comment were unsuccessful). Now, it seems, Brodie’s train runs on his own schedule.

Mike Brodie is an American photographer based in Oakland, California. His first book, A Period of Juvenile Prosperity, was released by Twin Palms Publishers on March 1, 2013. He currently works as a diesel mechanic.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com