Updated Nov. 26: In memory of Saul Leiter, who has passed away in New York at the age of 89, LightBox republishes a casual conversation with the photographer and painter, originally published earlier this year.

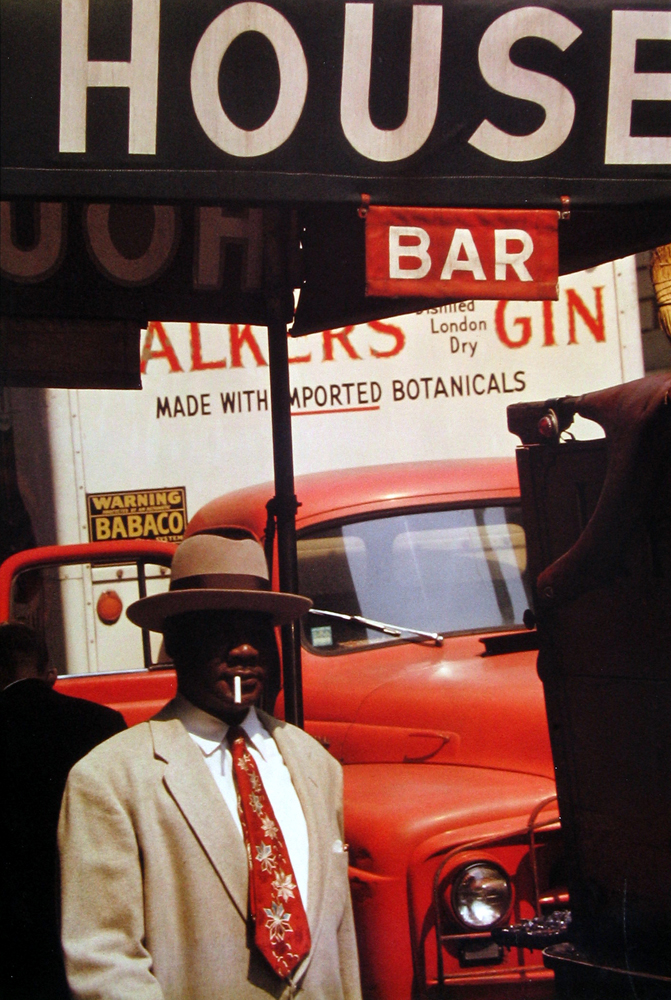

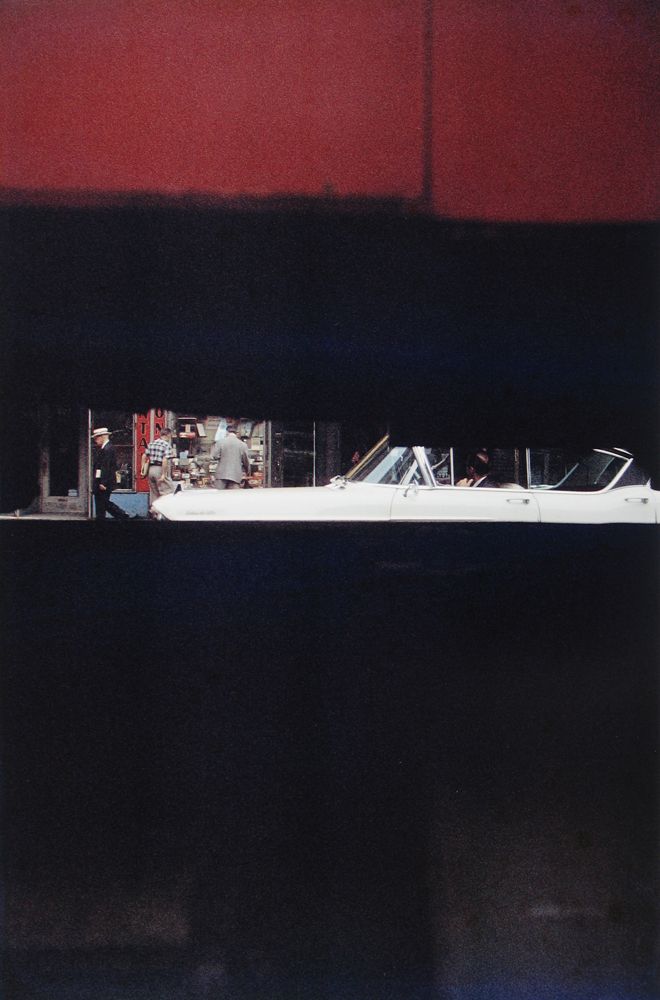

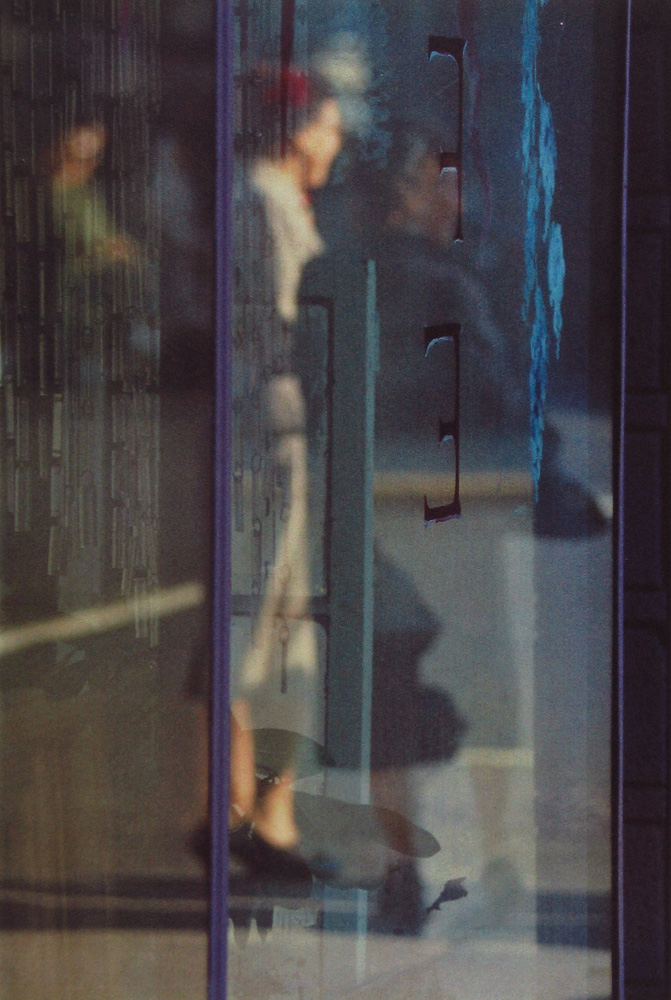

Saul Leiter is an original — a spirited, self-effacing artist who followed his own vision. His early black and white photographs, made in the mid-1940s, coincide with the birth of the New York School of street photography, but his serene, often-abstract images felt more pastoral than urban — in quiet contrast to the frenetic and visceral work of his contemporaries, and of the city itself. Congenitally independent, his work more closely aligns with the aesthetic of painters he reveres (Bonnard, Vuillard, Honami Koestu) than the work of the great photographers he knew and still admires (W. Eugene Smith, Irving Penn, Richard Avedon). And his color photographs predate those of “pioneer” William Eggleston by a quarter of a century.

Seven decades after he made his first photographs, Leiter’s work is finally receiving its due, with several exhibitions planned in the U.S. and Europe: a slideshow projection (with original transparencies) at the Milwaukee Art Museum; a new book, Early Black and White, to be published this summer by Steidl; and a recently completed documentary by Tomas Leach, In No Great Hurry. TIME sat down for a friendly conversation with the painter and photographer at the Howard Greenberg Gallery in New York. Below are some of the insights and recollections we came away with, in the artist’s own inimitable words.

Trailer for In No Great Hurry, directed by Tomas Leach

On His Early Days

“My brothers were rabbis. My grandfather was a rabbi. [But my father] wasn’t a typical orthodox rabbi. He was a linguist, a scholar, he read everything under the sun. He warned me against becoming a dilettante. (laughs). ‘You must avoid being a dilettante.’ I did love him, [but] I disappointed him. What can you do?

My brother once said [about me]: “Saul had this crazy idea that people oughta be happy. Life isn’t about being happy. Forget it!” (laughs)

I left home because I was unhappy, and came to New York [to become an artist]. When I look back I’m amazed that I was so badly prepared. I felt that I had nothing, and was close to going out of my mind.”

On A Talent for Indifference

“I’ve never been overwhelmed with a desire to become famous. It’s not that I didn’t want to have my work appreciated, but for some reason — maybe it’s because my father disapproved of almost everything I did — in some secret place in my being was a desire to avoid success.

My friend Henry [Wolf] once said that I had a talent for being indifferent to opportunities. He felt that I could have built more of a career, but instead I went home and drank coffee and looked out the window.”

On Art and Commerce

“I arrived at a way of looking and photographing that was, if I may say so, personal. It was a beginning of a certain kind of photography for me, and Steichen included me in an exhibition [Always the Young Stranger at MOMA where the prints] were just tacked to the wall — they weren’t given the kind of treatment that they get these days. I began to earn a living, and my mother was kind enough to keep me afloat. My father would have allowed me to sink.

I’ve always been rather impractical. I lived with someone [Soames Bantry, an artist with whom Leiter had a decades-long relationship] — well I didn’t live with her — but we were together in a way, and she was a very talented woman. But she didn’t work. She discovered that she could get away with not working because I tended to be kindly and overlooked certain weaknesses on her part.” (laughs)

“I had collections of Japanese prints, I owned Bonnard, Vuillard … it was a time when you could buy things [like that] cheap, and when I needed money I would sell them. Soames, I think, was unhappy about that. She saw her walls as the Vuillard went away, and the Bonnard went away. But my own view was that you have things for a while, and then they go off and they live in another place. They deserve to have another home.” (laughs)

“I owe a great deal to Howard [Greenberg, his gallerist], because he has sold my work and provided me with enough money so that I don’t have to worry about paying my bills. Howard is a very nice man, especially when you consider what some dealers are like. Some wanted to be artists, but they ended up being dealers and sometimes, in some corner of the brain, there’s a jealousy there.”

On Self-Importance

“I’m sometimes mystified by people who keep diaries. I never thought of my existence as being that important.

I have a deep-seated distrust and even contempt for people who are driven by ambition to conquer the world … those who cannot control themselves and produce vast amounts of crap that no one cares about. I find it unattractive. I like the Zen artists: they’d do some work, and then they’d stop for a while.”

On the Present Day

“The past few years, I have been doing what I call kitchen paintings. I get the little boards that they put between the bottles when you buy wine, and I make acrylic paintings. I wake up in the middle of the night and do one of these paintings while I’m heating the water for my coffee.

I go into Starbucks, I have my camera with me. I look at certain things. I haven’t printed a lot of those things, though. I’ve done a whole series out of my window, in color and in black and white, and it could be a little book — if I were of the mind to do it.”

On Being A Color Pioneer

“I’m supposed to be a pioneer in color. I didn’t know I was a pioneer, but I’ve been told I’m a pioneer. I’ll just go ahead and be a pioneer!

I find it strange that anyone would believe that the only thing that matters is black and white. It’s just idiotic. The history of art is the history of color. The cave paintings had color … [But] there has always been the idea in certain circles that form is more important, that to have too much color is not good, it distracts from your concentration.”

On Sequencing

“I don’t attach as much importance to sequencing [in an art book, for example] as other people do. To me the content is more important.”

On Intellectuals

“I’ve never been carried away by the great achievements of the intellectuals. They’re very often people whose ideas are grasped for only a short time.”

On Legacy

“There are certain people who like to be in the swing of things, but I think I’ve been out of the loop a lot of the time. When Bonnard died, one critic accused him of not participating in the great adventures of Modernism. And Matisse wrote a letter in which he defended Bonnard, saying that when he saw the Bonnards in the Phillips collection, he told Mr. Phillips, ‘Bonnard was the strongest of us all.’

I’m not like those photographers who went up to the top of the mountain and hung over and took a picture that everyone said was impossible and then went home and printed it and sold 4,000 copies of it and then went on and on with one great achievement after another.

Max Kozloff said to me one day, ‘You’re not really a photographer. You do photography, but you do it for your own purposes – your purposes are not the same as others’. I’m not quite sure what he meant, but I like that. I like the way he put it.”

Saul Leiter: Post-War Color will be on exhibit at the Rose Gallery in Santa Monica beginning Feb. 16th.

In No Great Hurry will be screened at the Thin Line Film Fest in Denton, Texas. Click here for more upcoming screenings.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com