Viviane Sassen’s gorgeous, inscrutable fine art images from Africa have earned her acclaim and a place in the Museum of Modern Art. But recently, her surreal and equally beautiful fashion photography has been garnering attention, too: in 2011, Sassen won the prestigious International Center of Photography’s Infinity Award for Applied/Fashion/Advertising Photography, and more than 300 of her fashion images are on view at Amsterdam’s Huis Marseille Museum for Photography through mid-March 2013 in a show titled, Viviane Sassen / In and Out of Fashion.

Born in Amsterdam, Sassen lived in Kenya — where her father worked in a polio clinic — between the ages of 2 and 5. Because the continent looms so large in her work, I asked her to describe her earliest memories from Africa.

“I remember,” she told me, “how Rispa, our nanny, woke me up one early morning and took me to a deserted football field to pick small white mushrooms. I remember the taste of sugarcane and ugali [a dish similar to polenta], orange Fanta and the bloody goat heads in the market in Kisumu.”

Returning to the Netherlands was difficult for her: “I didn’t feel I belonged in Europe, yet I knew I was a foreigner in Africa.”

As a young woman, Sassen enrolled in a university fashion design program and also modeled. Recalling her modeling work, she says that she “can relate to how a girl might feel in front of a camera: sometimes bored, tired or simply stressed or insecure. And then the shoes … three sizes too small but with killer heels. It’s not always fun to be a model.”

Nevertheless, she says she “got to know a lot of photographers; they made me aware that they controlled the image. That’s what I wanted, too; I wanted to be in control of the image … to create it.”

Sassen made the leap into photography. She recalls that “in the beginning, [photographers] like Nan Goldin and Nobuyoshi Araki [were] very important for my work because of their formal language, but also because they depicted their own lives in a way that appealed to me.”

A turning point in her own photography came in 2002 when she returned to Africa with her husband. The fine art photography she has made there in the past decade shines as some of the most original, unexpected work to emerge from the continent by a Western photographer. But one finds no victims of war or famine here; instead, the viewer confronts contemporary Africans engaged in sophisticated, if mysterious, dream performances.

“Working in Africa opens doors of my subconscious,” Sassen explains. “Sometimes, when I wake up in the morning after very vivid dreams or if I just suddenly have an idea, I sketch. My photographs are sometimes almost literal pictures of these sketches.” At other times, she says, “I might just find something on the street that excites me.”

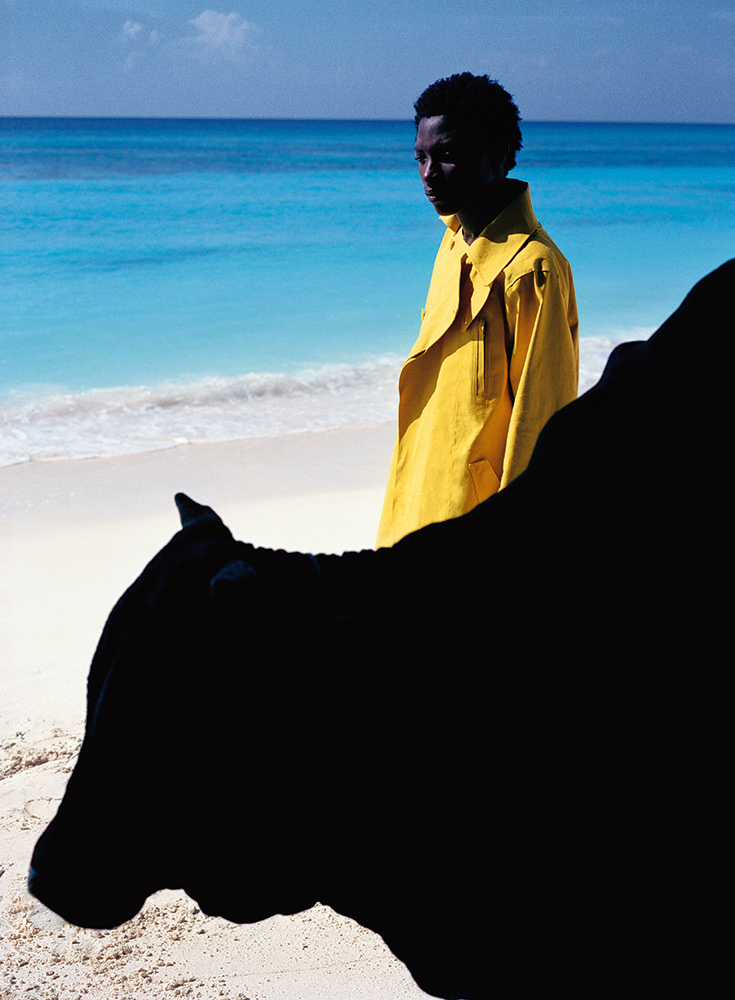

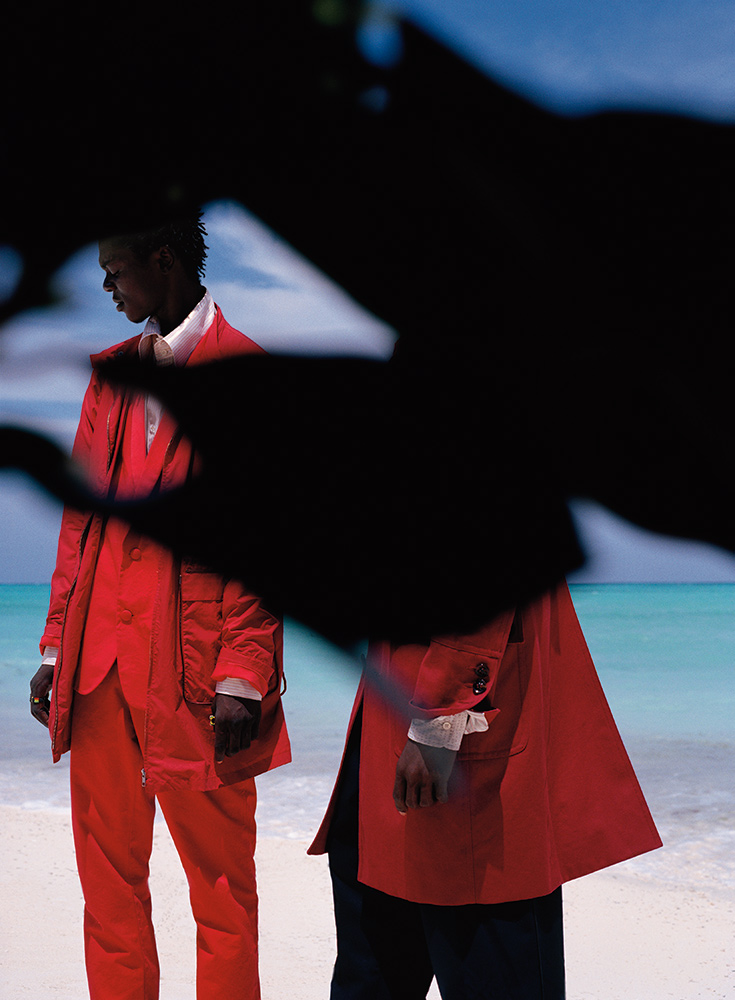

Her images are somehow primal and hallucinatory at once: two youths embrace in the dark, a giant banana leaf sprouting between them; a figure lies nestled in the diaphanous green cloud of a fishing net; a boy lounges on the ground, his limbs painted bright turquoise. Critic Vince Aletti says that Sassen “tends to treat the body as a sculptural element—a malleable shape that combines with blocks of shadow and bright color in arrangements that sometimes read like cut-paper collages, bold and abstract but full of vibrant life.”

One key part of the body that is often missing or obscured is the human face, as models turn away from the camera or appear with their faces cloaked in shadow. As Aaron Schuman noted in Aperture, the images might thus “appear to ignore the individuals they portray and instead inherently possess—maybe even propagate—the problematic histories, legacies, and relationships between Africa and the West. But perhaps in Sassen’s case this is the point, at least in part, and where the power of her photographs lies.”

Within these mirror-like voids, Sassen allows the viewer to reflect on the clichés and prejudices Westerners so often fall back on when engaging the vast continent and its inhabitants.

“I want to seduce the viewer with a beautiful formal approach,” says Sassen, “and at the same time, leave something disturbing.”

Sassen’s fashion work borrows much from her fine art—obscured faces, extraordinary color. The acute graphic sensibility of Sassen’s fine art, meanwhile, works wonders in magazine spreads. In an elemental way, though, the museum show and Sassen’s images (made for magazines like Wallpaper, Purple and Dazed & Confused, and for brands like Levi’s and Stella McCartney) don’t make sense at all.

As Sassen told the British Journal of Photography in its December 2012 issue, “I find exhibitions of fashion photography within the context of a museum rather problematic. Most fashion images aren’t art, they’re fashion photographs—which is fine, but if you put them in a museum, enlarged and in a frame, they become something else…. Art photography doesn’t have to serve any purpose, fashion photography does, and that makes a difference…. [Then] there are images which are really between art and fashion, which I hope I do myself.”

Sassen hit upon a solution to this conundrum: projecting fashion images on museum walls, so the work retains a “kind of disposable feel.” Furthermore, Sassen has said she doesn’t care much about clothes. “My interest is not the interest of the fashion industry. My interest is to make fascinating pictures…. It’s always about desire and fear, about making images that are both appealing and unsettling.”

Nevertheless, Sassen says she loves the “swiftness of fashion” as opposed to the “contemplated process of making art.” I asked her about the difference between shooting for magazines and shooting for advertisements.

“What I like about fashion magazines is that they create a platform to experiment and to work closely with people who can be super inspiring. I call it my laboratory. [It] should be like an adventure; not knowing where your play will lead you. When you’re working on fashion campaigns for a commercial brand it’s often much less experimental, but still creative in the sense that you have to match the pieces of a puzzle.”

Sassen has used a computer and a promotional flash drive to retouch some of her images, but mostly avoids it. “I think that something beautiful is even more charming when it’s not too perfect. You don’t want to feel the artificiality of the image, you want to believe in it. I feel related to reality, while slick images feel exchangeable.”

Sassen’s lifelong interest in Africa — and her ongoing explorations of her own subconscious — have contributed to some of the most riveting fashion photography being made today. For a photographer rooted in (or, as she puts it, “related to”) reality, her magazine work is a revelation.

See more of Sassen’s work at VivianeSassen.com.

Myles Little is an associate photo editor at TIME.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- How Far Trump Would Go

- Why Maternity Care Is Underpaid

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- Saving Seconds Is Better Than Hours

- Why Your Breakfast Should Start with a Vegetable

- Welcome to the Golden Age of Ryan Gosling

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com