Twenty-three years after it was eradicated in the United States, polio still stalks Pakistan, one of three countries left in the world where the devastating disease remains endemic. Prevention should be easy – all it takes is two drops of the vaccine, administered three different times, for a child to become immune. For years, polio has hovered on the brink of extinction in Pakistan, thanks in part to a 25-year effort by UNICEF, WHO, the CDC and Rotary International that has established a system of nationwide vaccinations that take place every six weeks. In 1988 there were 350,000 cases of polio in 125 different countries; today, that number is down to 176 cases in Pakistan, Afghanistan and Nigeria.

Hopes that polio could be knocked out for good in Pakistan faltered this summer when a pair of militant commanders in the ungoverned tribal areas along the border with Afghanistan banned the program, saying no vaccination teams should come to the area until the drone campaign against militants came to a halt — essentially holding the nation’s children hostage. The militant ban has spread amongst Pakistan’s Pashtun population, reaching as far as Karachi, in the country’s south.

There were 48 cases of paralytic polio last year in Pakistan, down from 154 in 2011. And while the cases are concentrated in the Pashtun speaking populations of Khyber Pakhhtunwa Province and the tribal areas, many of them have direct links to Gadap Town, Karachi’s biggest slum. Home to more than 400,000 people, of which 60,000 are children under the age of five, the tightly packed warren of concrete-block low-rise apartment buildings and small family compounds has become something of a black hole for government services. There is only one basic health clinic to serve the entire population, no sanitation services, no water treatment and a high likelihood that waste water is mixed with drinking water. For polio, it is the perfect storm, combining limited access, bad hygiene, low education levels and severe malnutrition: the polio virus has recently been found in water samples collected from the fetid stream that runs through the slum, a popular playground for area children. One polio worker recounts watching young children play tea party there, sipping stream water from the lids of water bottles scavenged among the heaps of rotting refuse lining the banks.

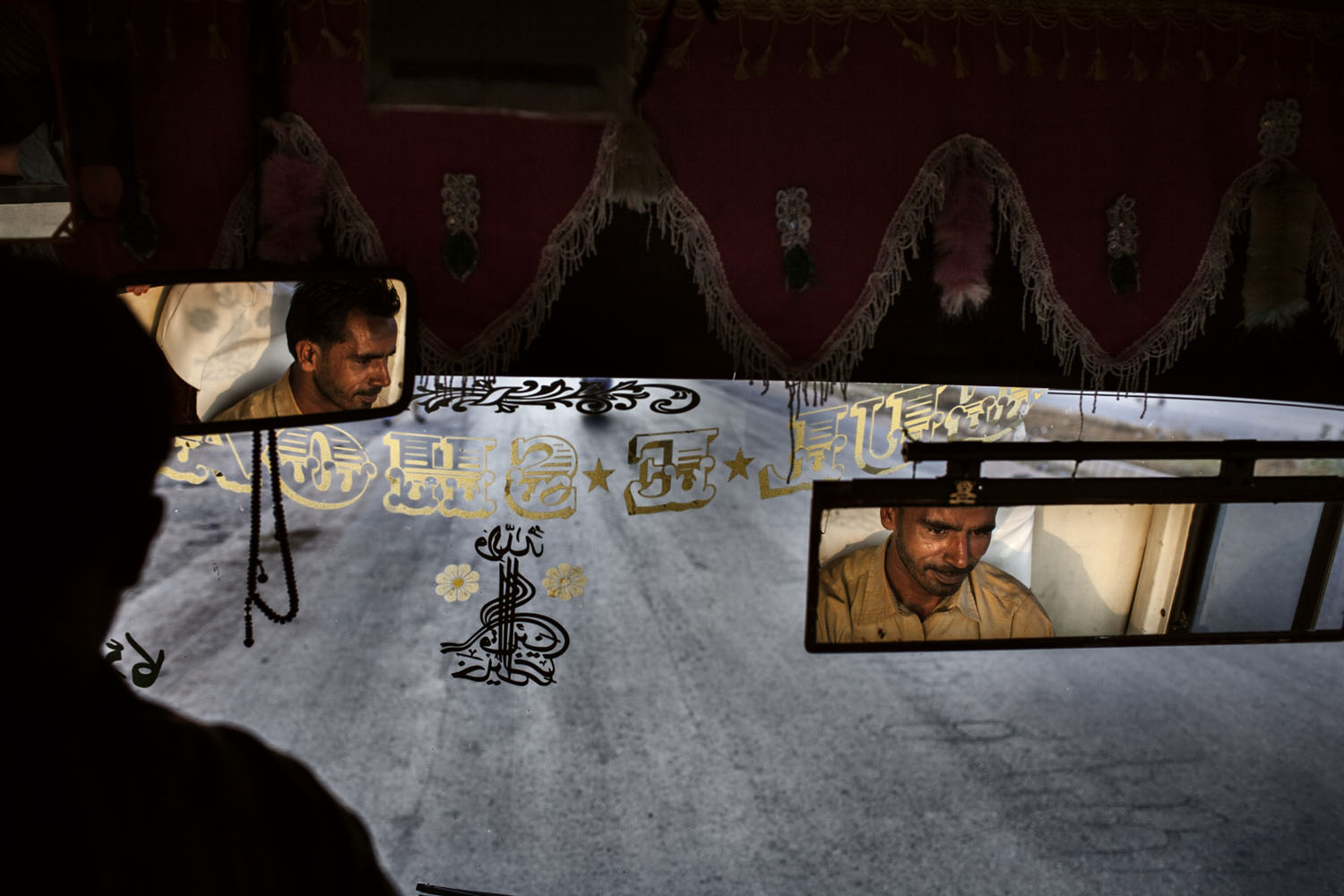

Pashtun-speaking migrants from the tribal areas dominate the area, and militant networks have made inroads among the population. Local officials call Gadap town “mini Waziristan,” in reference to an area near the Afghan border that is home to both the Pakistani Taliban and al-Qaeda linked militants. It’s not much of an exaggeration. In Gadap town, women, if they are seen at all, wear the trademark shuttlecock burqa of the Pashtun heartland. A recent survey conducted in Karachi by the World Health Organization noted that Pashtuns account for 75 percent of Pakistan’s polio cases even though they are only 15 percent of the population. Pakistan will never be free of polio, concluded the report, until a way is found to persuade poor Pashtuns to vaccinate their children. The Pakistani government is working with local communities on an education campaign, and making sure that every child on a public bus coming into or out of Karachi gets the drops. Still, some families have had to learn about the value of the vaccine the hard way.

Not so long ago, every child in Muhib Banda, a Pashtun village not far from the provincial capital of Peshawar, was vaccinated each time the polio teams came through. Local shopkeeper Saiful Islam says that he made sure his sons were first in line. But in late May, rumors swept through the town, as vicious and quick as a virus. “Some people were saying that the polio vaccine was made of pig urine, or monkey urine,” says Islam. “They said that it was a conspiracy to make Muslim children infertile. I believed them.” When the vaccinators came through a few days later, he refused to answer their knock. He refused again in July. And then his six month-old daughter Sulaim came down with a fever. When she recovered, she could no longer move her legs. It’s likely that she will never be able to walk. “Our ignorance made her paralyzed,” says Islam. He has pledged to join the fight against the disease, praying that Sulaim will be its last victim.

Diego Ibarra Sánchez is a Spanish documentary photography based in Pakistan.

Aryn Baker is the Middle-East bureau chief for TIME.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com