It is 6 p.m., and darkness has just fallen on the Lacandon jungle, a dense patch of rainforest in Mexico’s southernmost state, Chiapas. A cry rings out: “Food circle!” At this signal, hundreds of people emerge from the forest and gather in a clearing, forming a circle, holding hands. They start to chant, softly, “Om … Om …” while lifting their joined hands toward the sky. The chanting stops as suddenly as it began, and a vegan dinner is served from huge steaming pots.

These men and women, who travelled to this spot in the vicinity of Palenque’s pre-Colombian ruins from dozens of different countries around the globe, are here with one aim in mind: to witness the end of the world on December 21, 2012, a date that marks the end of the Mayan calendar. They are part of the “rainbow movement,” a post-hippie collective that emerged in Oregon in 1970 around the teachings of writer Barry Adams and gemstone specialist Garrick Beck. Its members gather annually across the U.S. on July 4th.

Most expect they won’t be around for next summer’s gathering.

There are no leaders in the movement. “All decisions are taken 100 percent consensually by talking circles,” explains Bolivia, a 32-year-old Briton. The camp functions without money: food is prepared by a group of volunteers and handed out for free. Other necessities can be bartered. Trading currencies include sweets, crystals or Snicker bars. Alcohol, meat and loudspeakers are forbidden.

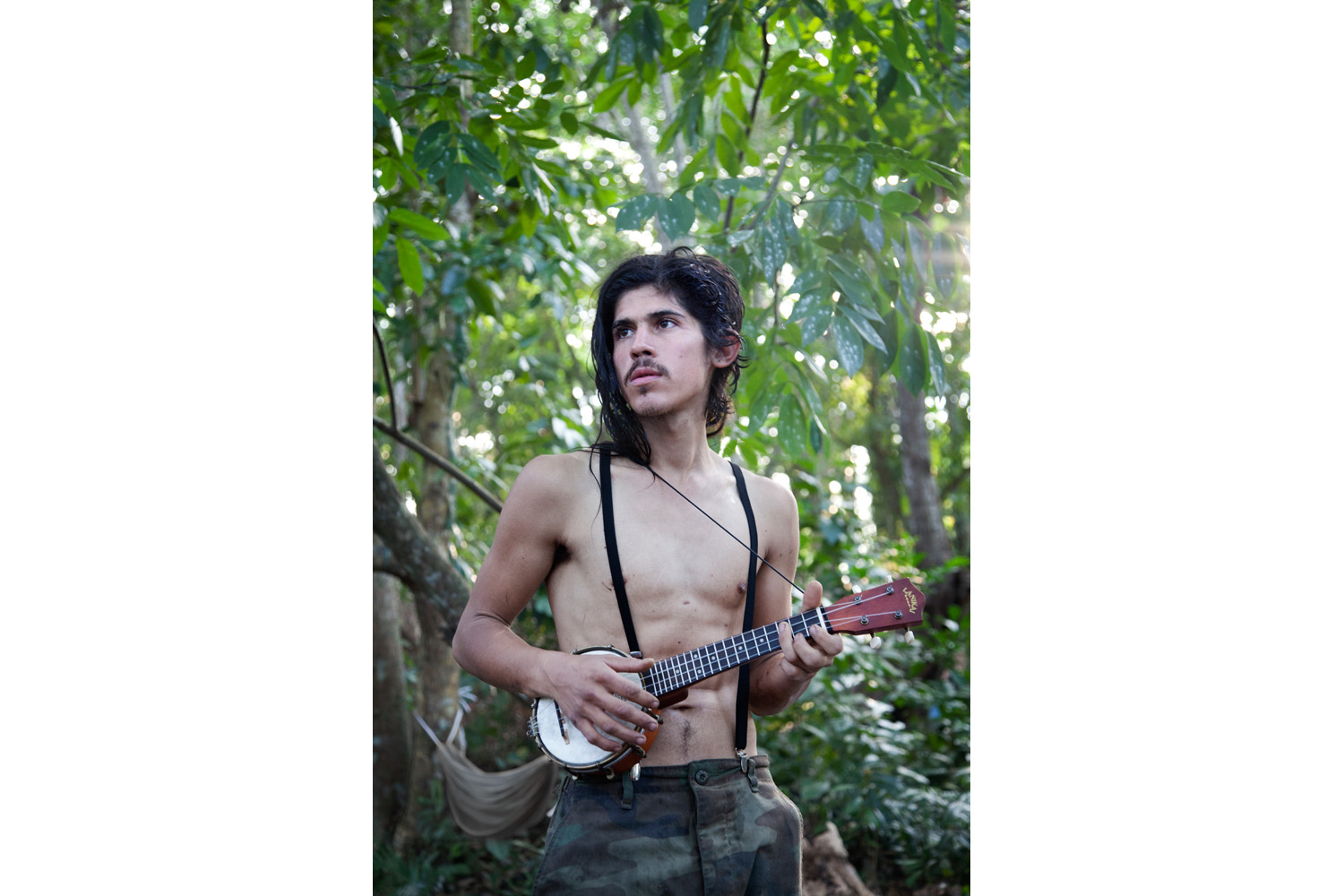

Rainbow Gathering attendees, who call themselves The Family, spend their days bathing naked in the river, doing improvisational theater, juggling or practicing yoga. Twice a day they gather for the food circle. Most live in the manner they do in hopes of showing the rest of the world that an alternative way of life — “without wars, guns or money,” as Bolivia puts it — is possible. Among Family members there is a lot of talk of chakras, inverted pyramids and “portals” that will open on December 21st.

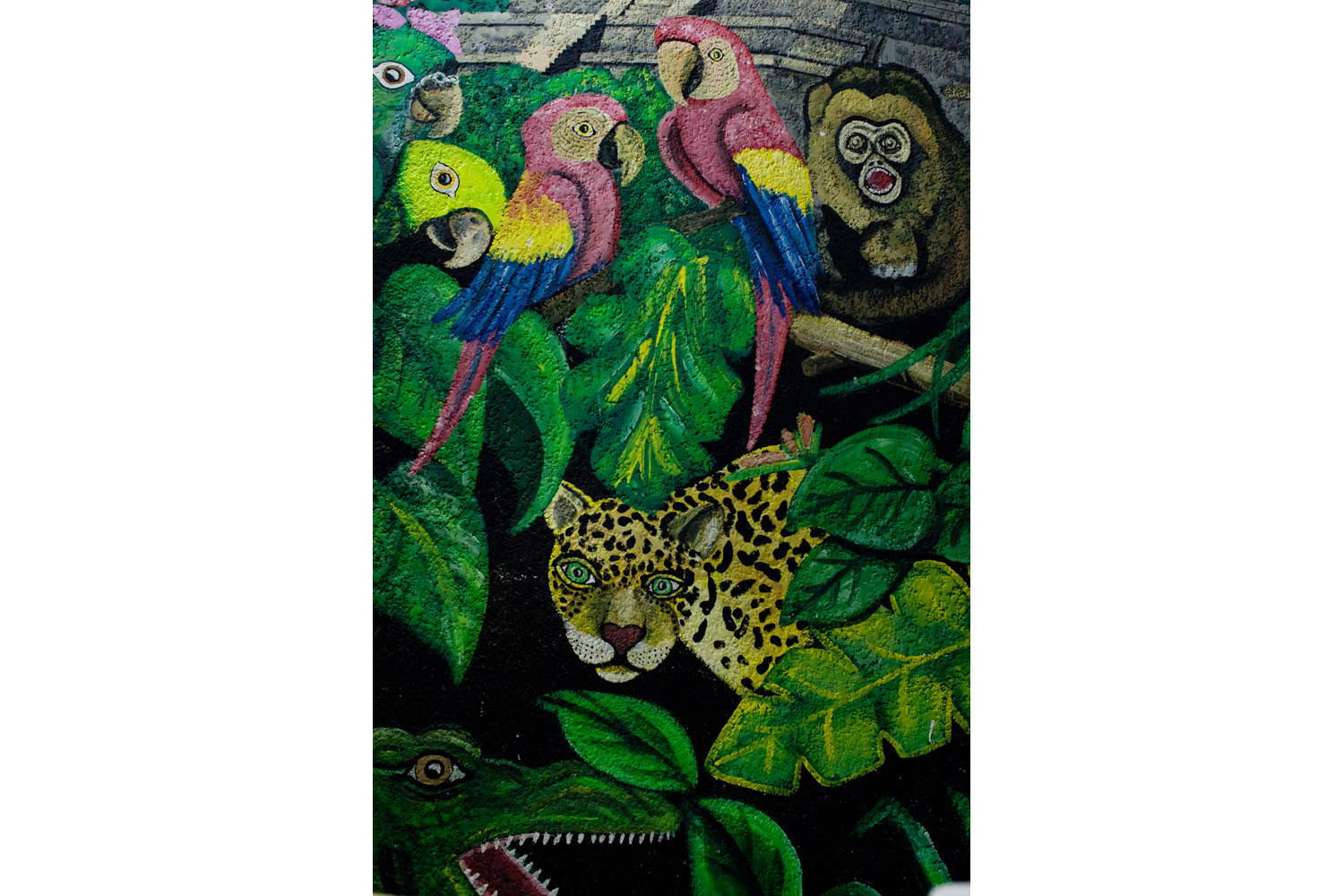

The end of the Mayan world, meanwhile, is a much more down-to-earth affair. It is taking place roughly 100 miles from where the Family is gathered, in a small village called Lacanja Chansayab that houses the last descendants of a civilization that dominated Mesoamerica from roughly 250 to 900 AD. There are fewer than a thousand Maya left. They speak a language, Hach T’ana, that closely resembles that of their ancestors. They wear their hair long, don white tunics, hunt with bows and arrows and revere their gods by burning rubber dolls in ceremonies that symbolize human sacrifice.

Or, at least, they did until recently. The Lacandon Indians emigrated from the Yucatan peninsula in the 18th century to flee the conquistadors, and remained there almost untouched until the middle of the 20th century, when loggers and archeologists started to arrive in the area. The erosion of their culture accelerated in 1998, with the opening of the road from Palenque. Electricity followed shortly after, in 2000.

As we pull into the village on a sunny day in December, change is apparent everywhere. A truck is unloading a fridge, a washing machine and a TV. Music blares from the loudspeakers of the Refugio de Esperanza, the Pentecostal church that set up shop here 13 years ago.

“The hardest thing for me was learning to wear shoes,” remembers 53-year-old Chan K’in.

But modernity also brought with it more serious woes: “A lot of the kids leave the village to attend secondary school in nearby towns,” explains 26-year-old Victorino. “When they are away from their family, with no one to watch over them, they often start taking drugs.” Lacanja Chansayab lies just a few miles from the border with Guatemala, along one of the main cocaine routes.

But what really disrupted village life was the advent of money. In 2004, the Mexican tourism authority decided to sponsor ecotourism infrastructures in the village, in part to ensure Lacandon loyalty in the face of the 1994 Zapatista rebellion in neighboring communities.

“We gave 550,000 pesos (43,200 dollars) to eleven families to build three cabañas each,” says Alberto Morales Cleveland, the local tourism representative.

Other families had to manage without that help. “The head of the village shared the subsidies among his friends and the community is now split between those who received money and those who didn’t,” sighs Martin, who operates an independent eco-lodge.

“I don’t believe December 21st will be the end of the world. But for us, life as we knew it has certainly come to an end,” laments his brother, Ismael.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- TIME’s Top 10 Photos of 2024

- Why Gen Z Is Drinking Less

- The Best Movies About Cooking

- Why Is Anxiety Worse at Night?

- A Head-to-Toe Guide to Treating Dry Skin

- Why Street Cats Are Taking Over Urban Neighborhoods

- Column: Jimmy Carter’s Global Legacy Was Moral Clarity

Contact us at letters@time.com