Photographer Omar Mullick has spent the last decade passing through the countries of Central Asia on assignment. Here, he reflects on his photographs of a Pashtun cinema in Karachi, a space he found defied the preconceived images of the region.

These photographs were created, if I am brutally honest, from a loss of faith. Not in my religion or way of life, but from my understanding in how the eye of documentary photography portrays the Muslim world.

I didn’t buy it: the blurred melancholy and humorless conviction with which we documented native, usually Muslim peoples. It did not resonate—not even slightly, and even if I registered good intention in the work, it never mitigated my feeling that there were a thousand ways of looking at people in the West and only one way of looking at other people on the brunt of war. They were often confined to one visual language, or, to extend the metaphor, one set of visual phrases: suffering, victimhood, violence and trauma. And in the effort to prompt outrage and underline how bad war was, their subjects were often confined to the ‘other’. More specifically, people never surfaced in photographs—only symbols of war. What resulted was the worst absence possible in a photograph of another person: empathy.

The resulting photographs were shot, I realize now, as a response to that.

They were taken in Karachi at a Pashtun cinema before I was scheduled for an embed in Afghanistan. Working on a project called Basetrack and a documentary film about a Pashtun runaway boy, the photos were snapped on my days off. This place was my retreat, just as it was the retreat for the subjects in my photographs. My work, I hoped, was a portrait of people as they collectively exhaled. And in that I also hoped they kept, modestly enough, the company of photographers that emphasized sympathy over a desire to continue the string of visual metaphor: Kuwayama’s doves at Mazar E Sharif, Balazs Gardi’s tender Afghan father holding his son or Ladefoged’s The Albanians.

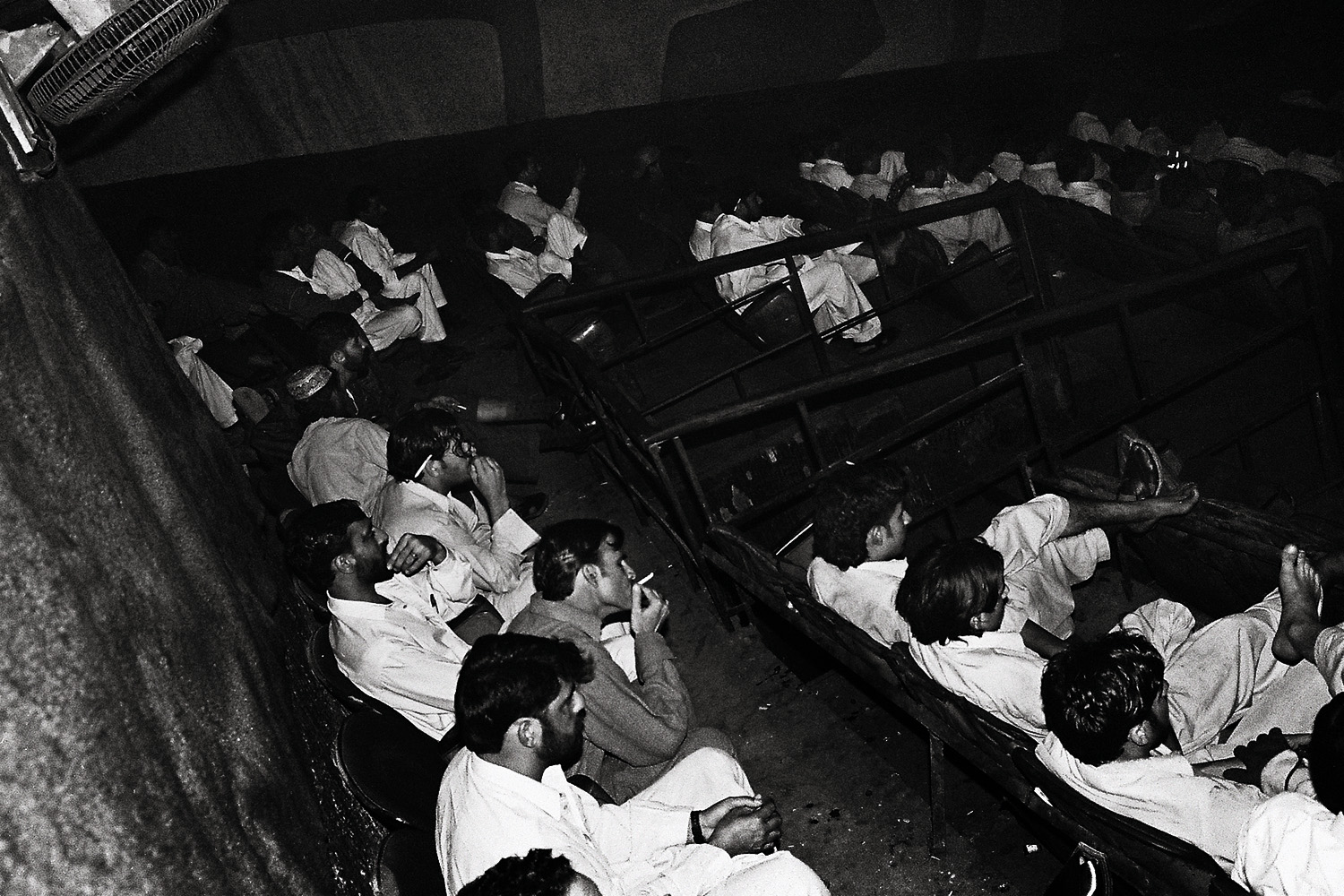

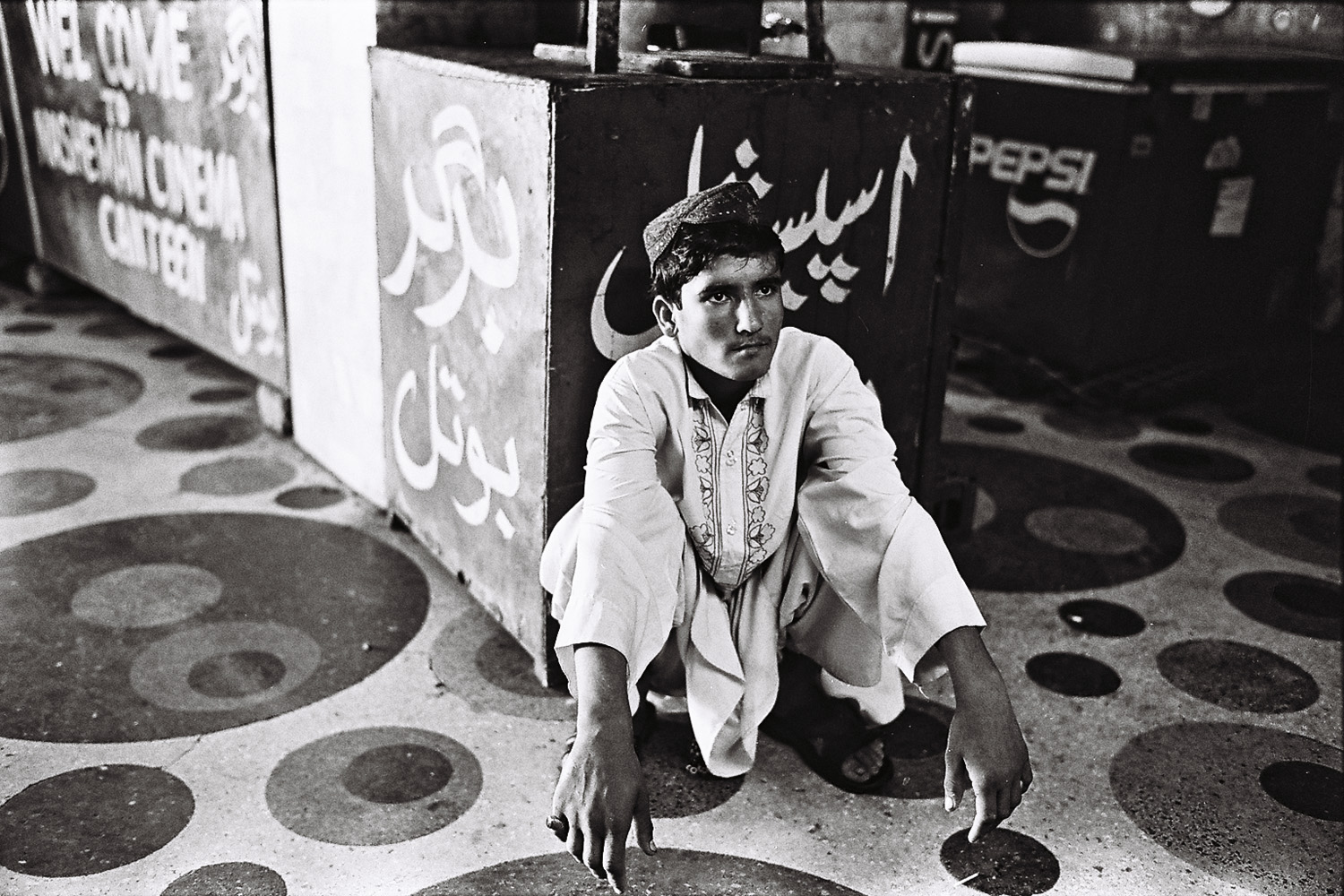

Pashtuns are known by legend and myth as warmongers, kohl-eyed and unforgiving, even unconquerable patriarchs to the last man—the blood and muscle of the Taliban. Here, displaced and withdrawn from their beloved mountains and heaped en masse in Karachi’s urban sprawl, they came to this movie theater—feared by outsiders—to see films and hear songs in their native tongue. And I—with my personal stories of bloodlines running all the way to Kandahar and Waziristan—schoolboyishly wanted to lose myself in their fold.

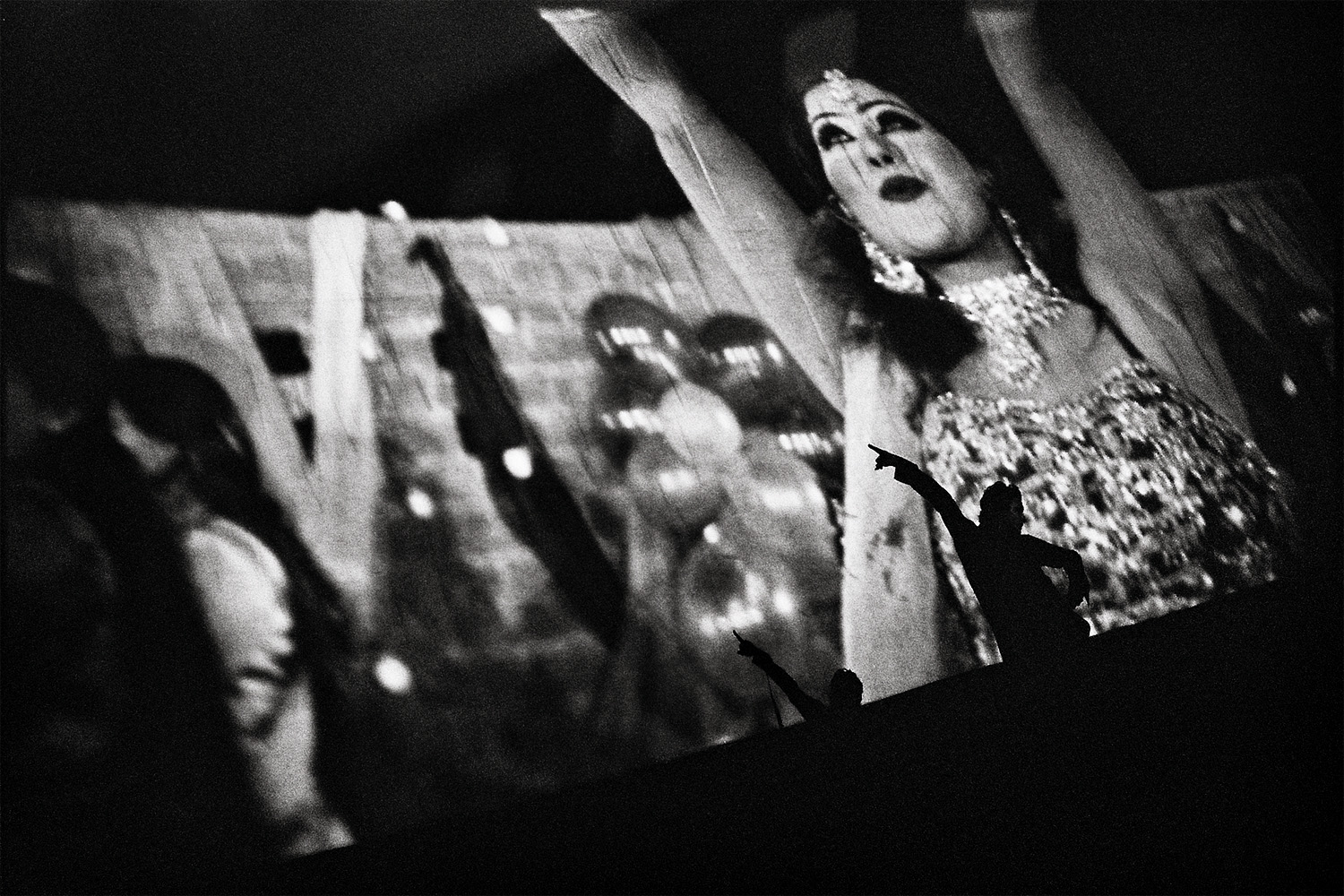

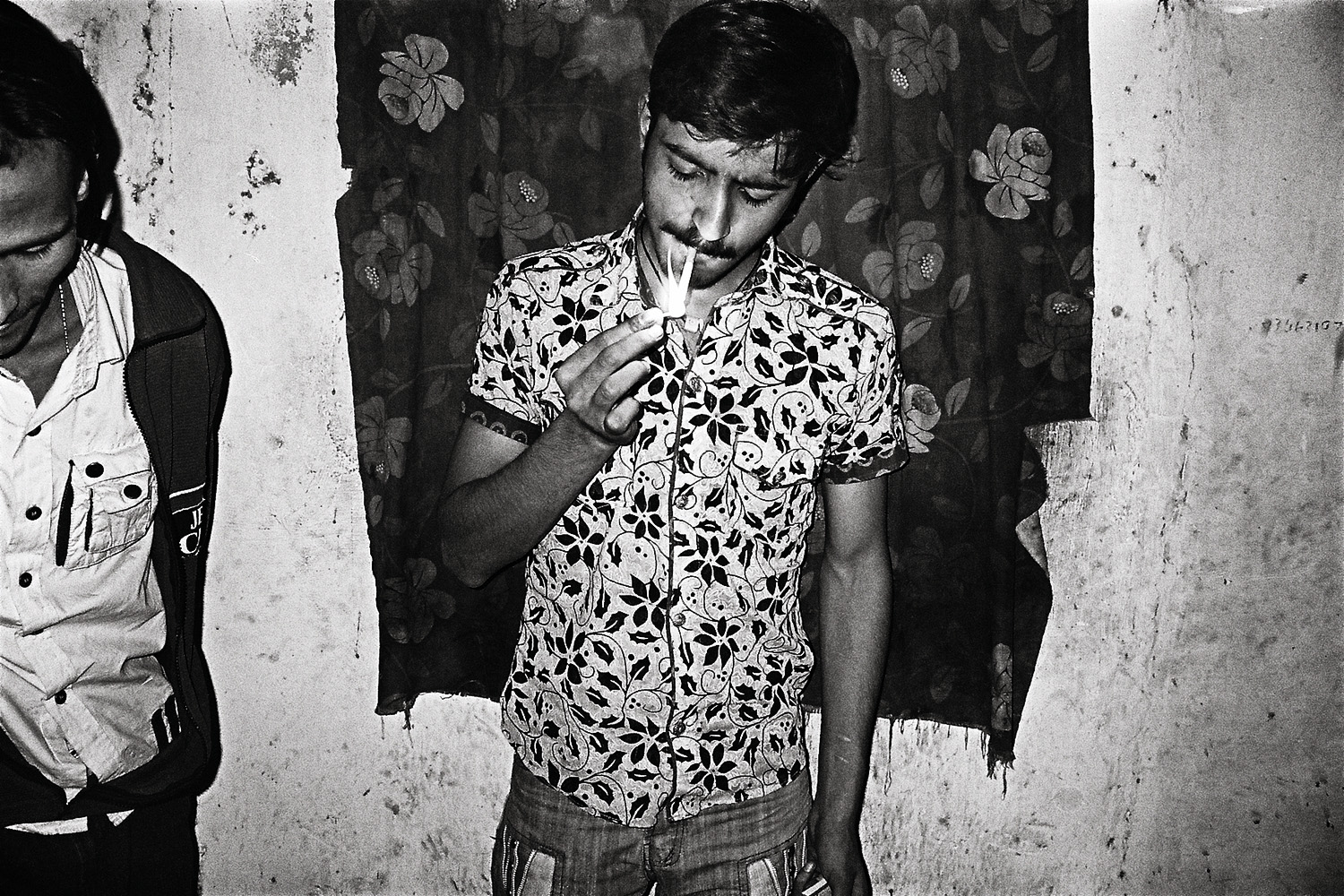

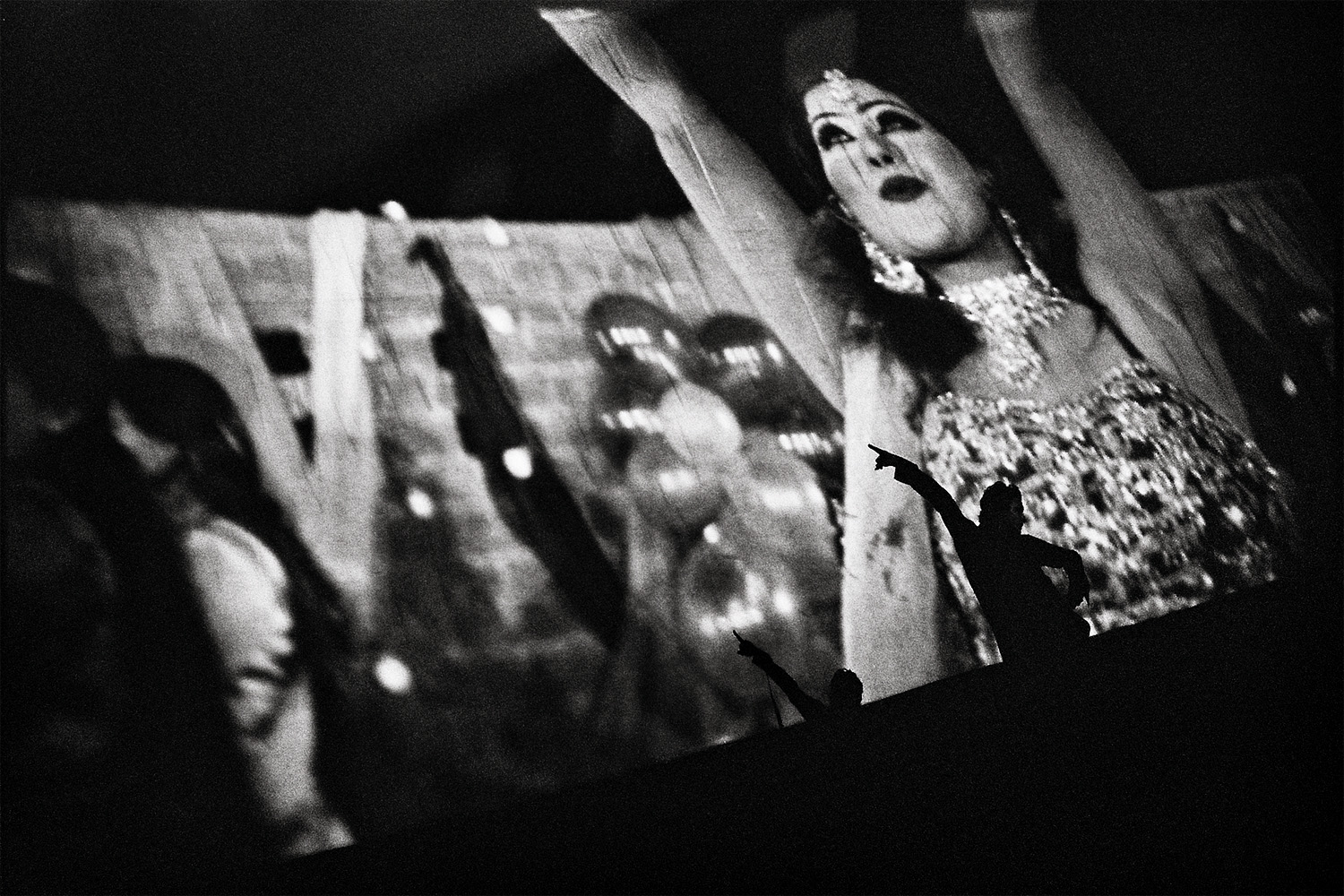

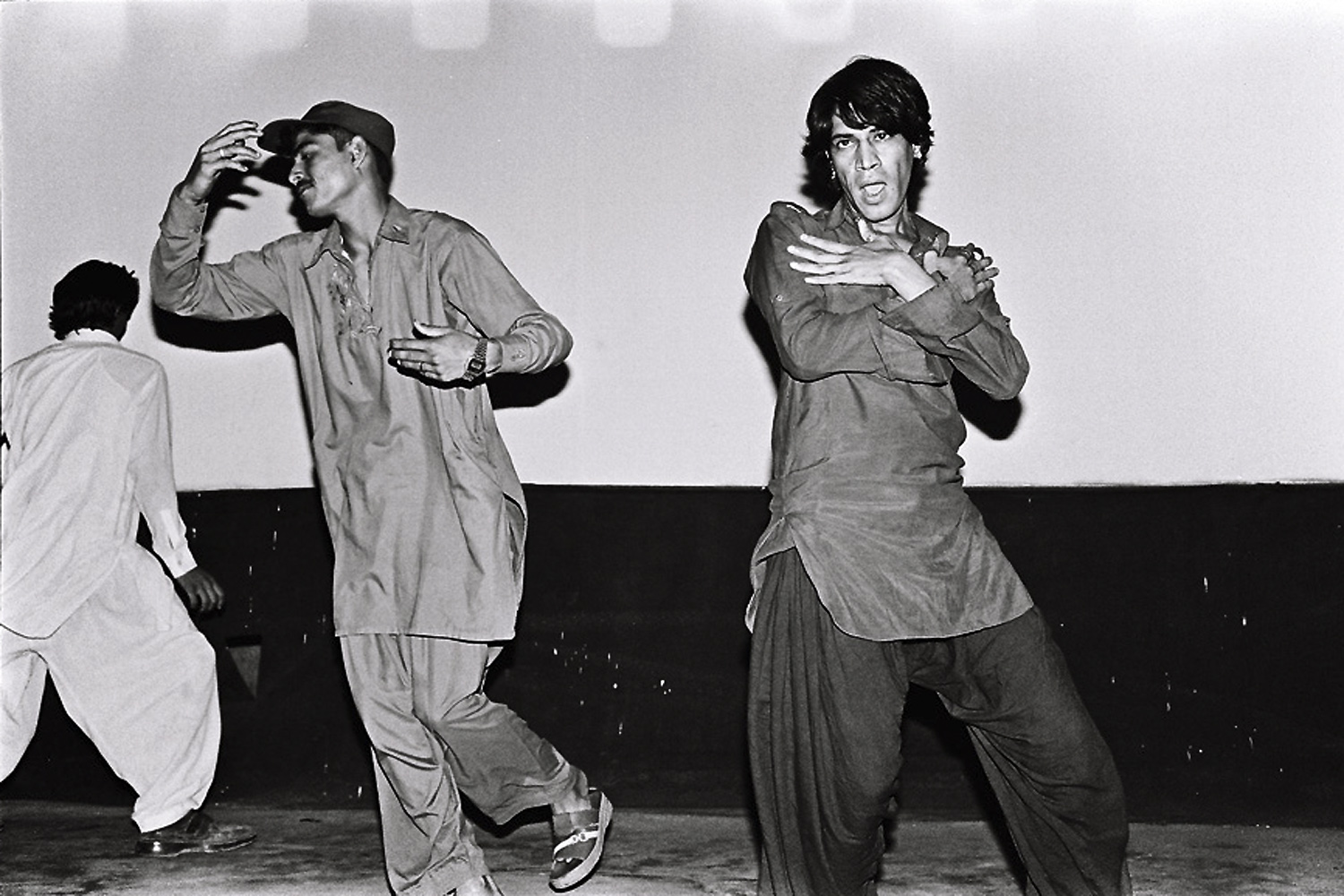

Men huddled and laughed in the aisles, smoking hash in advance of the film, people who saved their pennies for stale popcorn or samosas to be had in the intermission. Also men who, left alone, sat in the front aisles waiting in anticipation for a Pashto song to come on and then rushed the screen to dance against the projection to the song, cheered on by all. Runaway boys, who had made their way from Afghanistan or Waziristan to Karachi to pick trash by day, now chose the afternoon after Friday prayers to see a film. They preferred the sound of cinema to the buzzing drones that soundtracked their nightmares. Then there were the drug dealers, the boys looking to pick up johns by the bathrooms and the bulk of men who swore to kill any pedophiles they found taking advantage of children. But mostly it was of people at rest, disarmed. They were having fun.

These were men and young boys at ease enjoying themselves. In that they mirrored the loose pop flash photos I took of friends back home. I photographed the cinema barely looking through the viewfinder, the camera lofted above the fray and through ongoing laughs and phrases in Pashto, asking them what Waziristan looked like and who had been to Kandahar. And then I would shoot more, telling stories about my grandmother and her pride at being Pashtun and my mother’s own deep reservoirs of will and piety—markers they would surely recognize. In this recognition I found the most personal visual language I could muster.

Shoot them like you would your friends at home, I told myself: free of abstraction, their dignity intact. Shoot a portrait they might recognize of themselves, something they might love, something that may make them smile. At least once, let’s do that.

Shoot them as if your loss of faith in photography were redeemable, as if an image might actually be a chalice for humanity and you were all going to pass around the cup.

Shoot them as if your faith were already back.

Omar Mullick is a photographer and filmmaker based in New York City. He was an embedded photographer in the Basetrack project out of Afghanistan in 2011. His work on Muslims in America titled Can’t Take It With You received a solo show in 2009 at Gallery FCB in Chelsea, N.Y., and his recent film These Birds Walk was selected for 25 new faces of Independent Cinema in 2012.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com