Davide Monteleone traces the genesis of his new book of photographs, Red Thistle, to 2007, when he heard about a film festival going on in Grozny, the capital of Chechnya. At the time, Chechnya had been locked down for nearly a decade under a special security regime. Known as the KTO, the Russian acronym for “counter-terrorist operation,” the regime had meant years of martial law, curfews and random searches enforced by the Russian military. Not exactly the place for something like Sundance–the region’s film festival was a fluke, a rare chance for some foreigners to have a look around, and Monteleone took it. With his companion, Lucia Sgueglia, who would end up writing the text for Red Thistle, he would sneak out of the guarded hotel to explore Grozny.

“We did this until the Russian troops would catch us and take us back,” Monteleone said. “Then we would go out again.”

What he found was a region slowly restoring the rhythm of life—a weird, entrancing, pensive rhythm—after two devastating wars with Russia fought between 1994 and 2000. After the second war, the U.N. had deemed Grozny “the most destroyed city on earth,” but with billions of dollars in postwar Russian aide, the city had been rebuilt and revived. Over the next five years, Monteleone would return to Chechnya and the surrounding regions of the Caucasus Mountains as often as once a month.

“A lot of work had been done on the wars and the human rights abuses,” he said. “We wanted to study everyday life.”

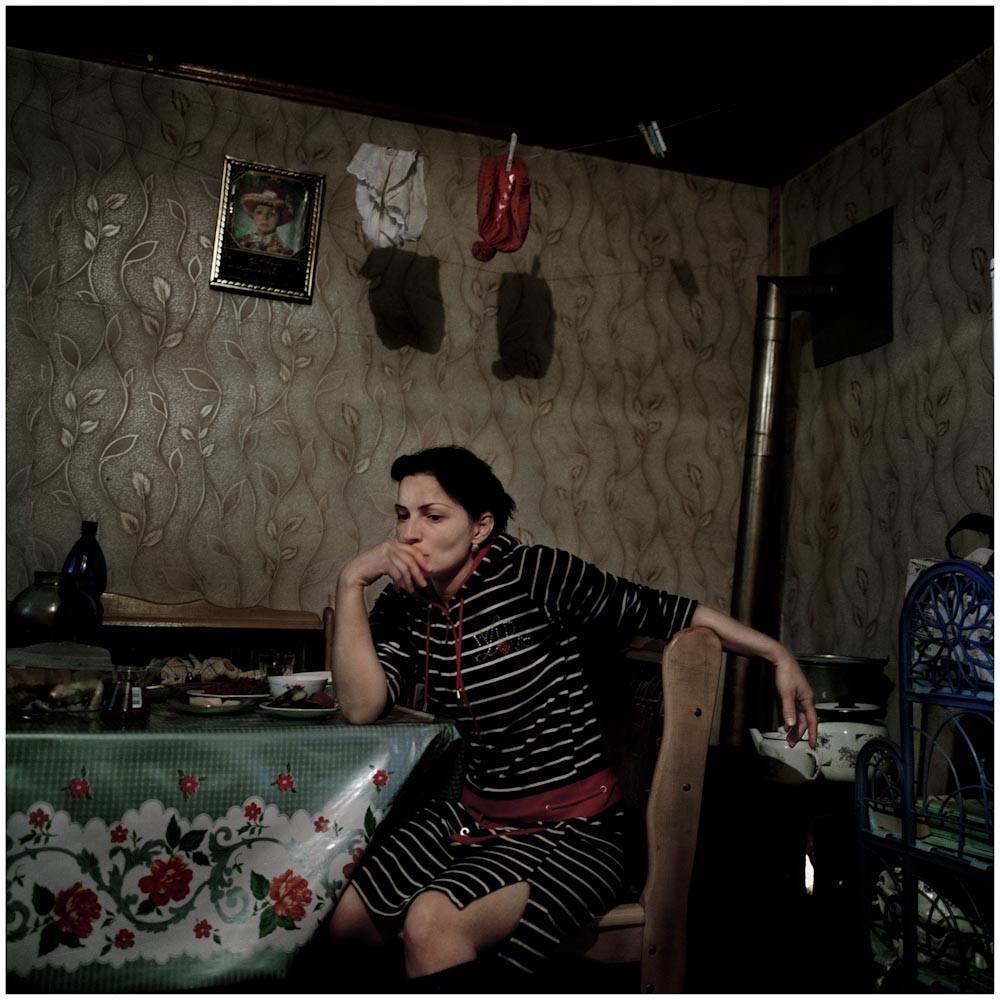

In 2008, the KTO regime was lifted in Chechnya and travel there became easier, but life was still colored by Russia’s shadow and the legacy of the Soviet Union, which ruled this predominantly Muslim region for almost 70 years. So the settings of Monteleone’s photographs—from the beat-up old Zhiguli cars to the destitute apartment blocks—have a distinctly Soviet texture, a drab, heavy latticework that seems to press against the people inside it. Smiles are not common on the faces in his photos, but they seem to have a stubborn glow amid the grayness that surrounds them.

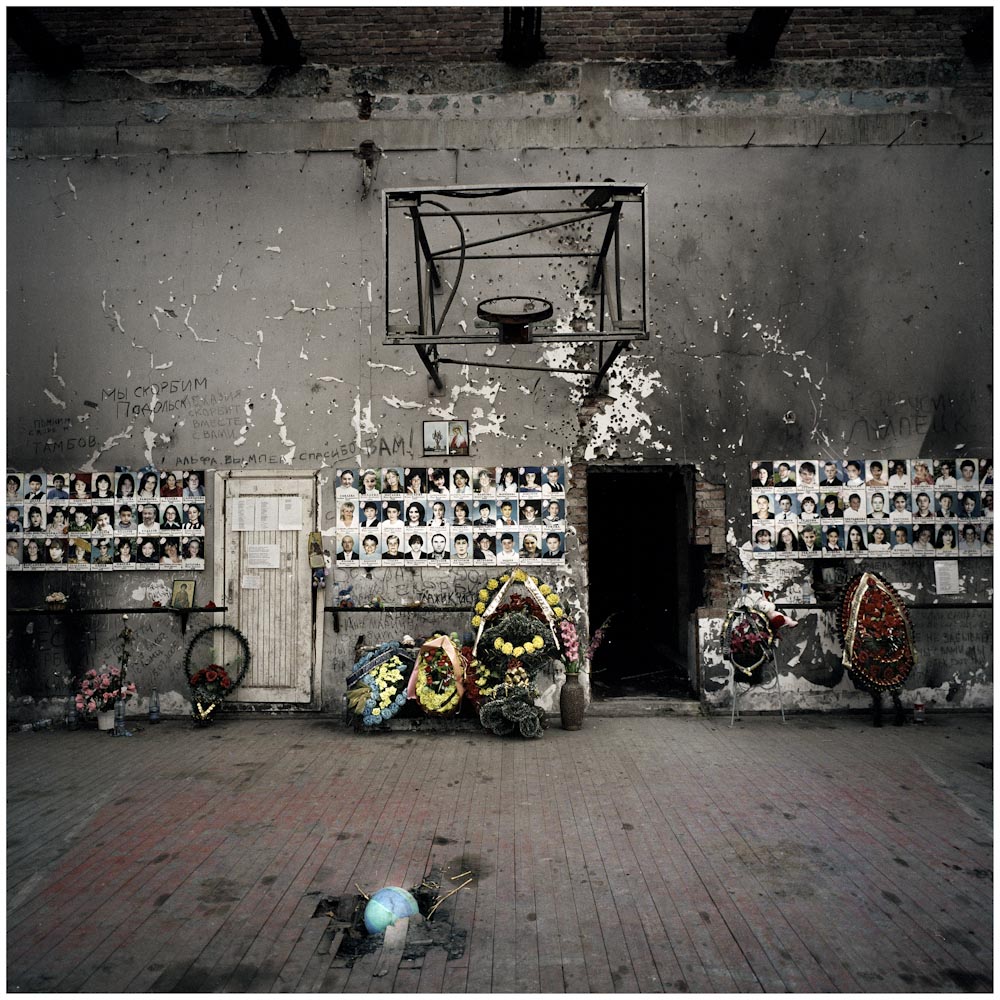

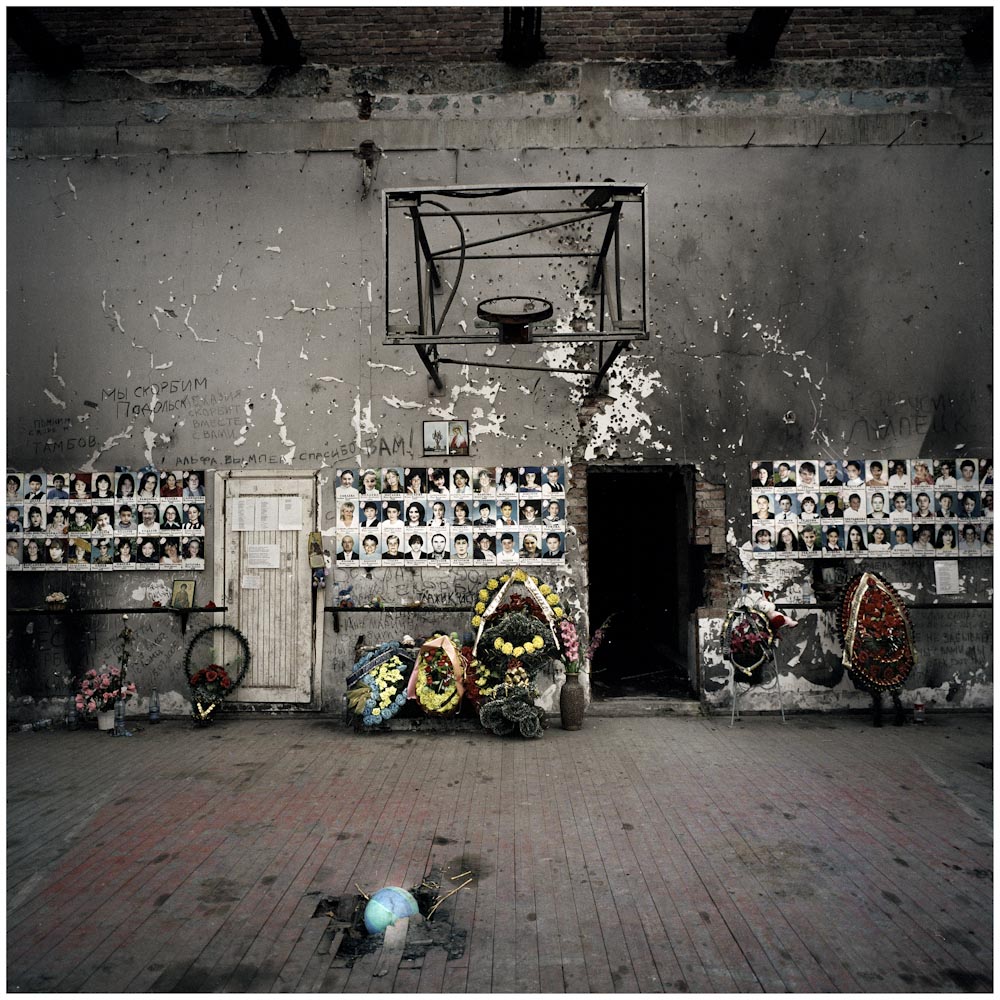

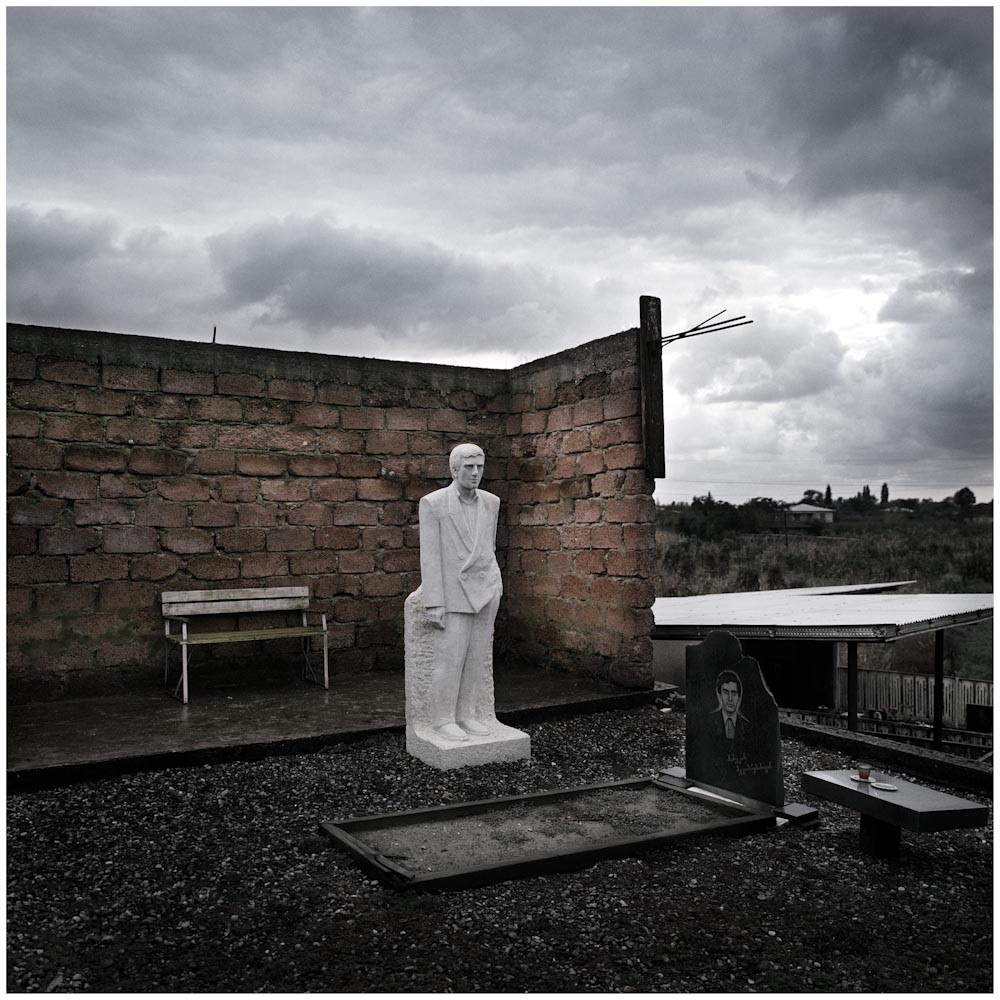

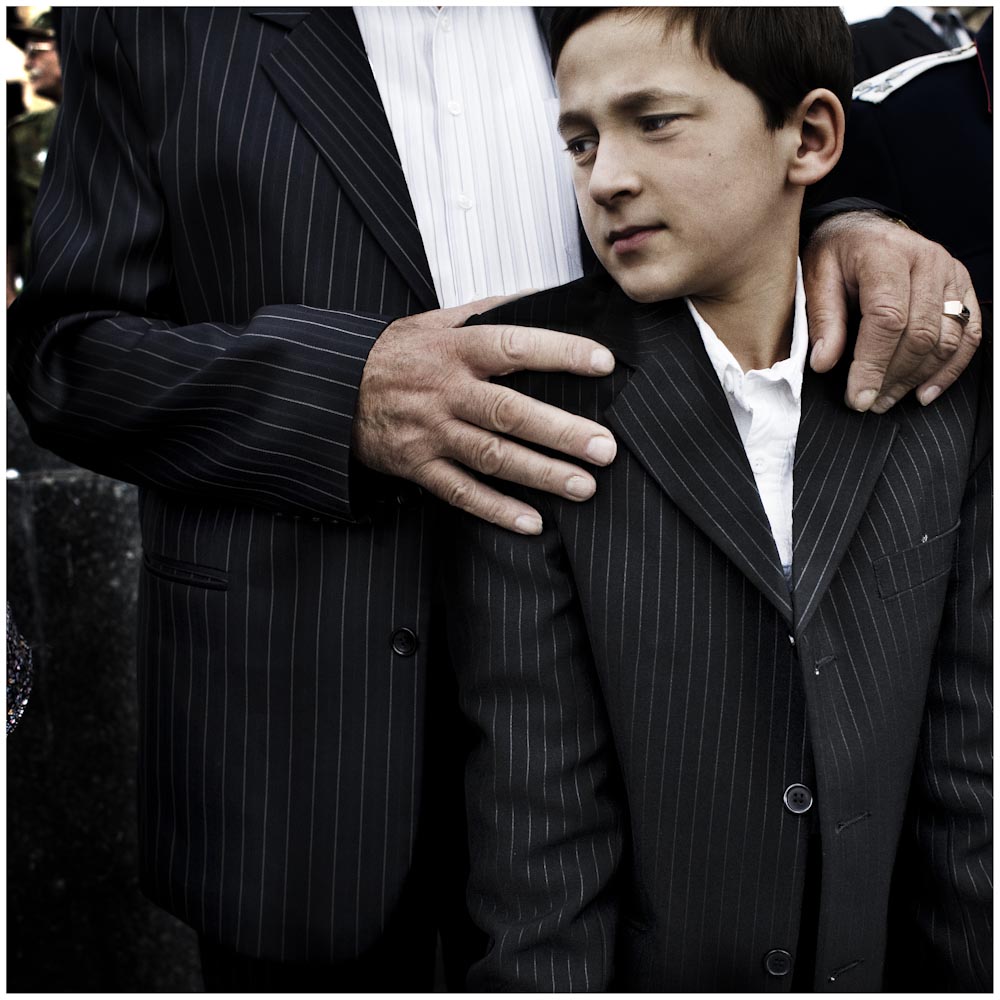

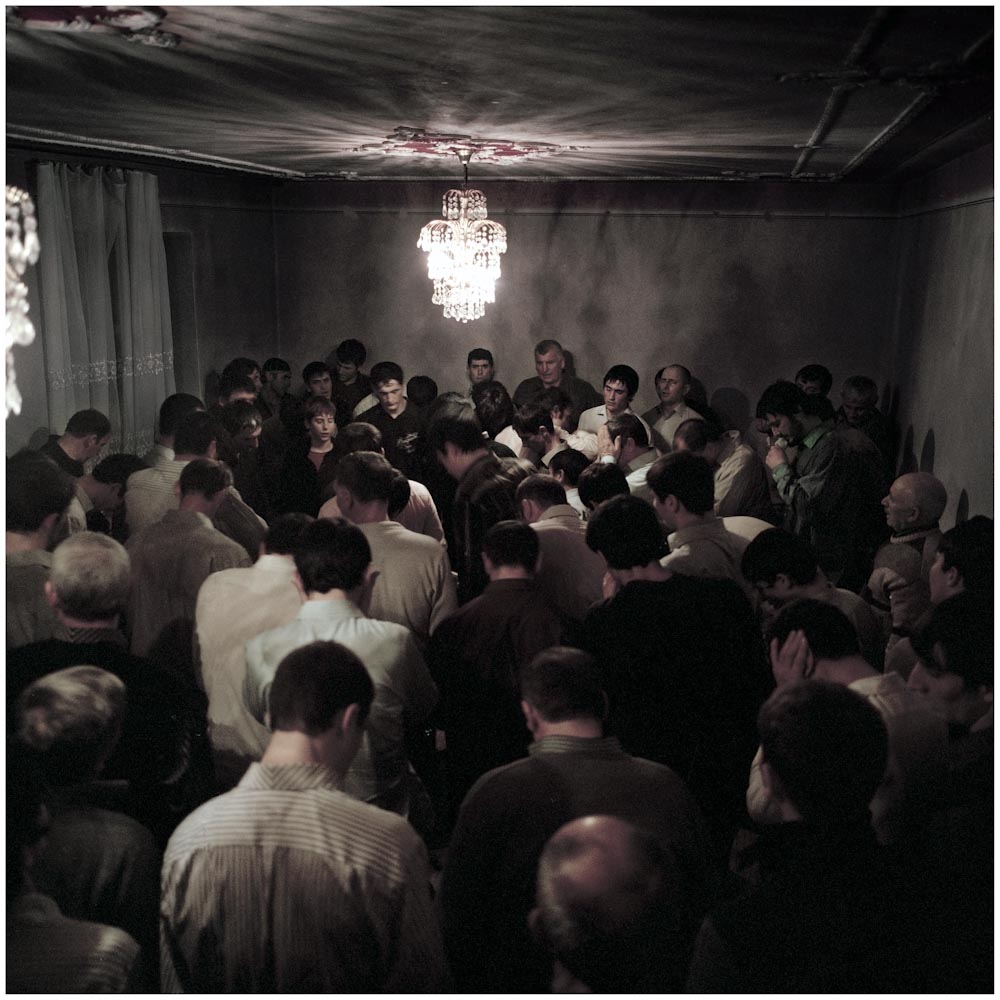

A common theme, predictably, is death, which is so insistent that it approaches a dulled ubiquity. If there is a kind of music to life in the Caucasus, mortality is its drumbeat in Monteleone’s work. In one frame, a woman in a black headscarf hurries along the sidewalk, not seeming to notice a stream of blood flowing toward her from a bull that was slaughtered in the street. There are weddings and funerals, and both seem to occasion equal measures of melancholy and warmth. At one wake in Chechnya, a group of men perform the Dhikr, an Islamic ritual which, in the local Sufi tradition, involves hours of rhythmic dancing and chanting until the men fall into a collective trance.

“You know that you’re in Russia,” says Monteleone. “But at the same time, life is structured in such a way that you feel closer to Persia or the Middle East.”

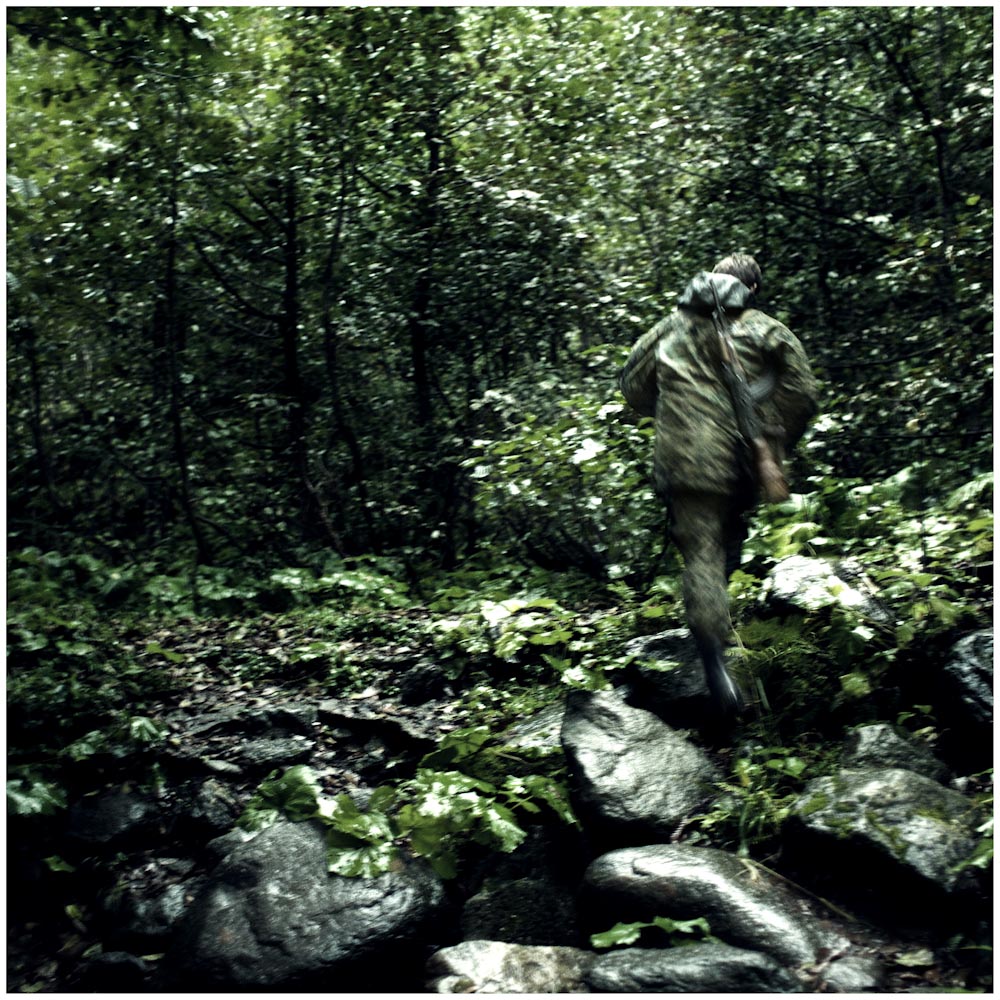

That is part of the duality of the Caucasus, which remains a world between worlds. The ongoing insurgency against Russian rule creeps in to remind you that the war goes on—a house stands demolished in one frame after Russian tanks moved in for a counter-insurgency strike—but there is also reconciliation: a group of men from one family walk down a mountain toward a mosque, where they resolve a blood feud with another family that had caused generations of strife. The overall picture is sad but not despondent, and there is resilience in almost every frame.

The unifying image of The Red Thistle comes from the opening scene in Lev Tolstoy’s novella Hadji Murat, which begins with a man trying to pluck a crimson thistle from a ditch in the Caucasus mountains. The thistle fights back, stabbing his hand with its brambles, and only gives in when he has frayed the stem and mangled the flower. “What energy and tenacity!” the man thinks. “With what determination it defended itself, and how dearly it sold its life.”

Simon Shuster is TIME’s Moscow reporter.

Davide Monteleone is a photographer with the VII agency. See more of his work here. Monteleone’s latest book, Red Thistle, was recently released by Dewi Lewis publishing.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com