What does prison look like?

In her latest body of work, Sailboats and Swans, Israeli photographer Michal Chelbin challenges viewers to re-imagine the answer to this question. Working with her husband and co-producer, Oded Plotnizki, Chelbin spent three years photographing prisons in Ukraine and Russia from 2008 to 2010.

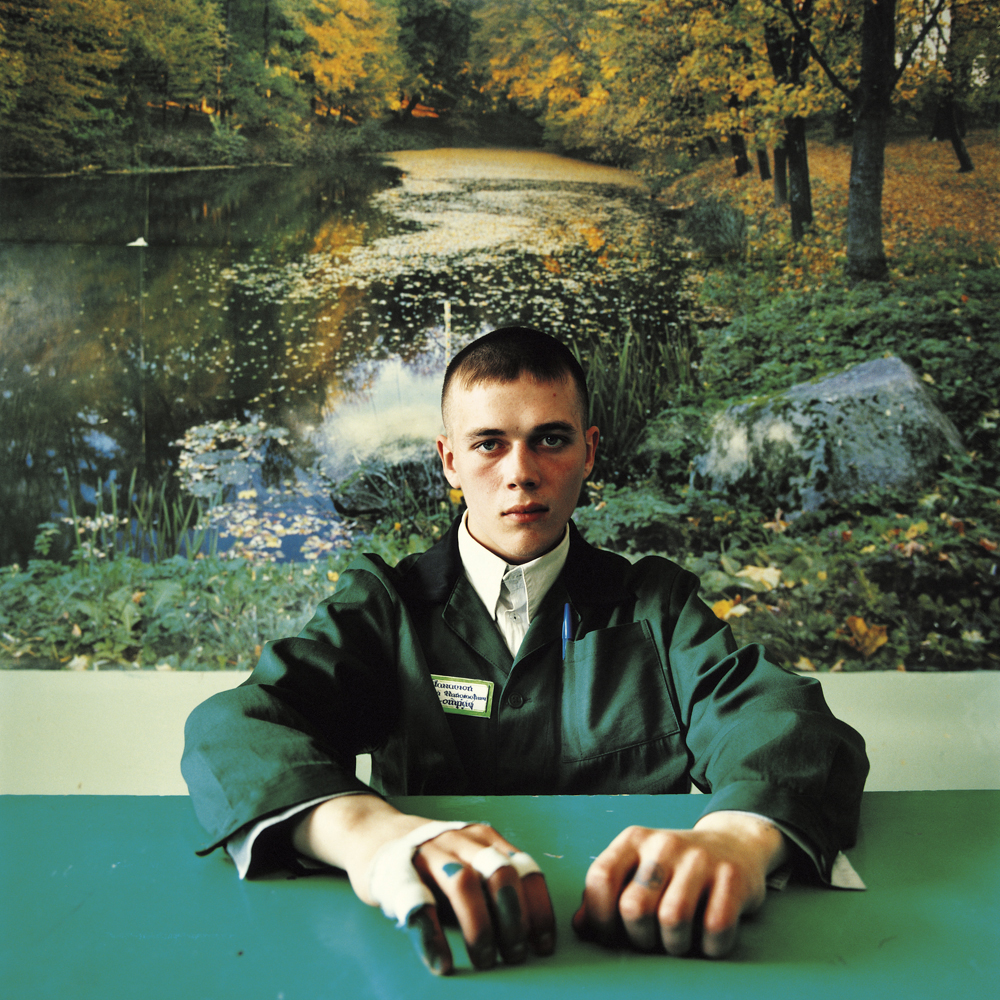

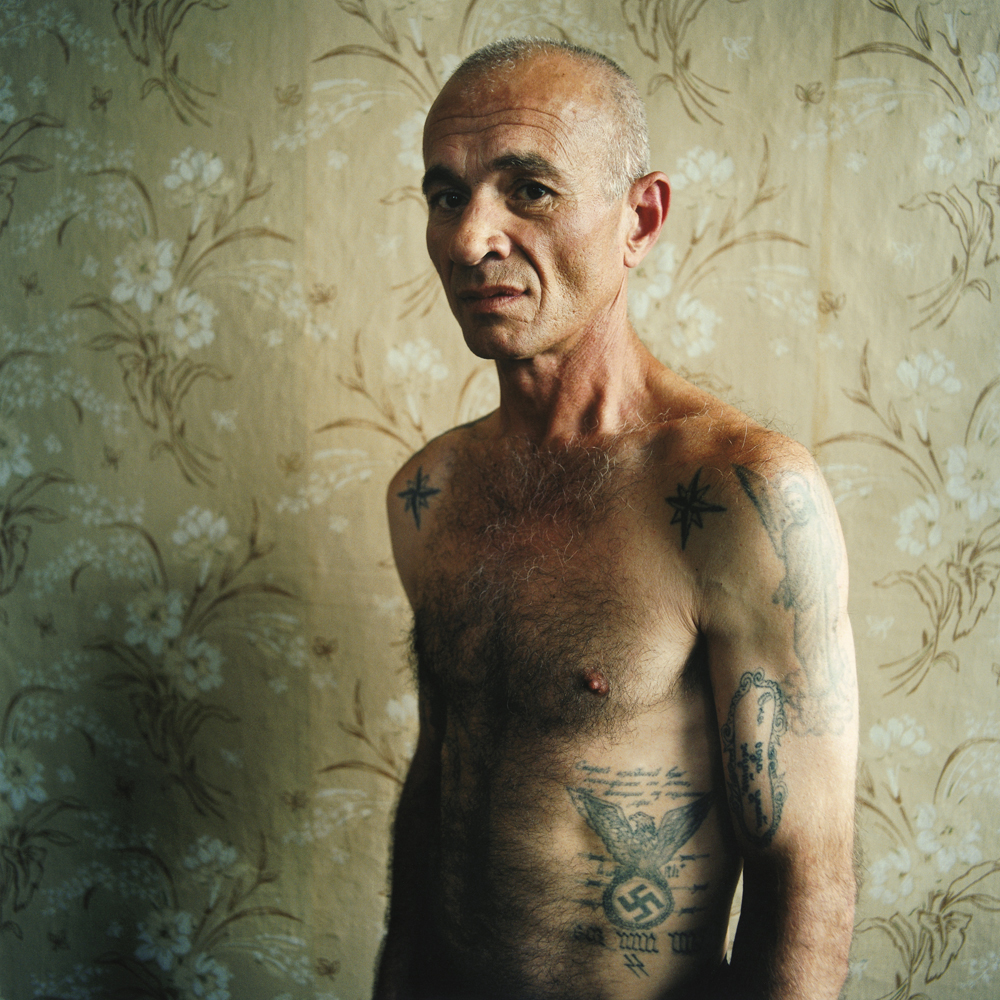

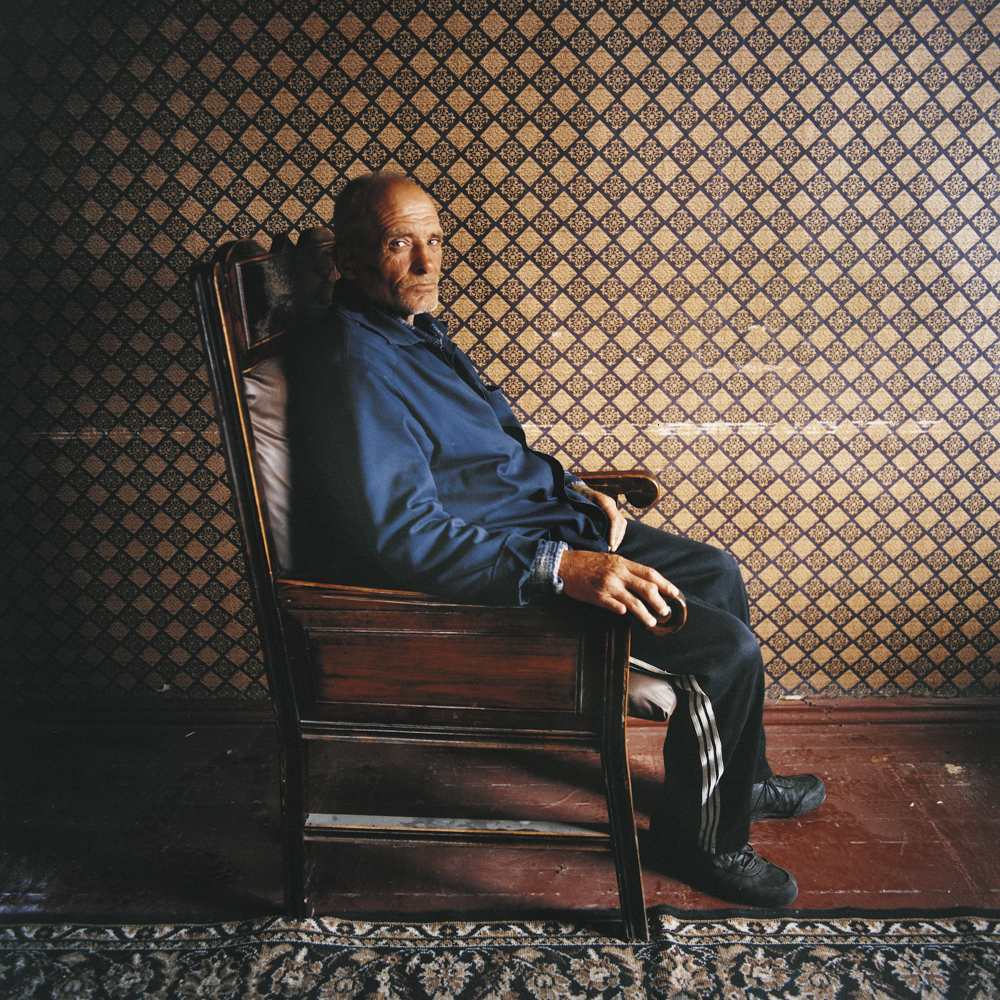

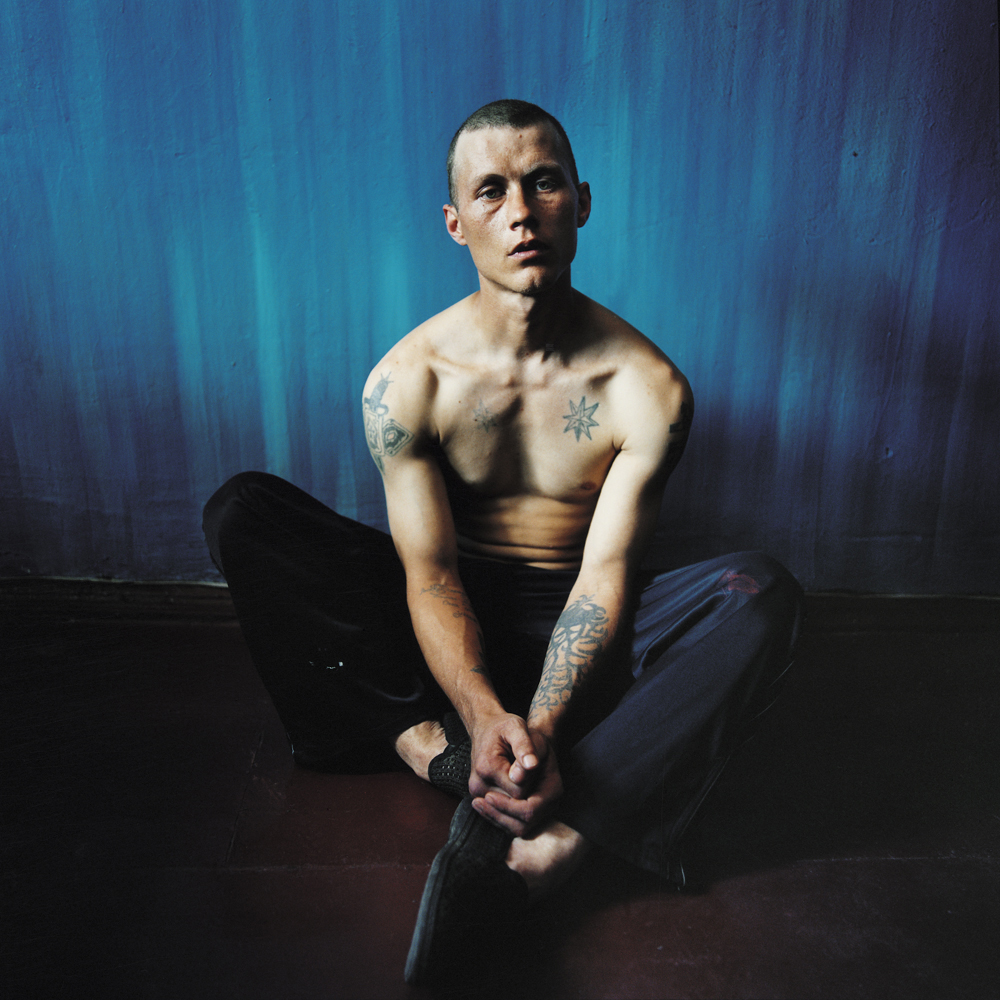

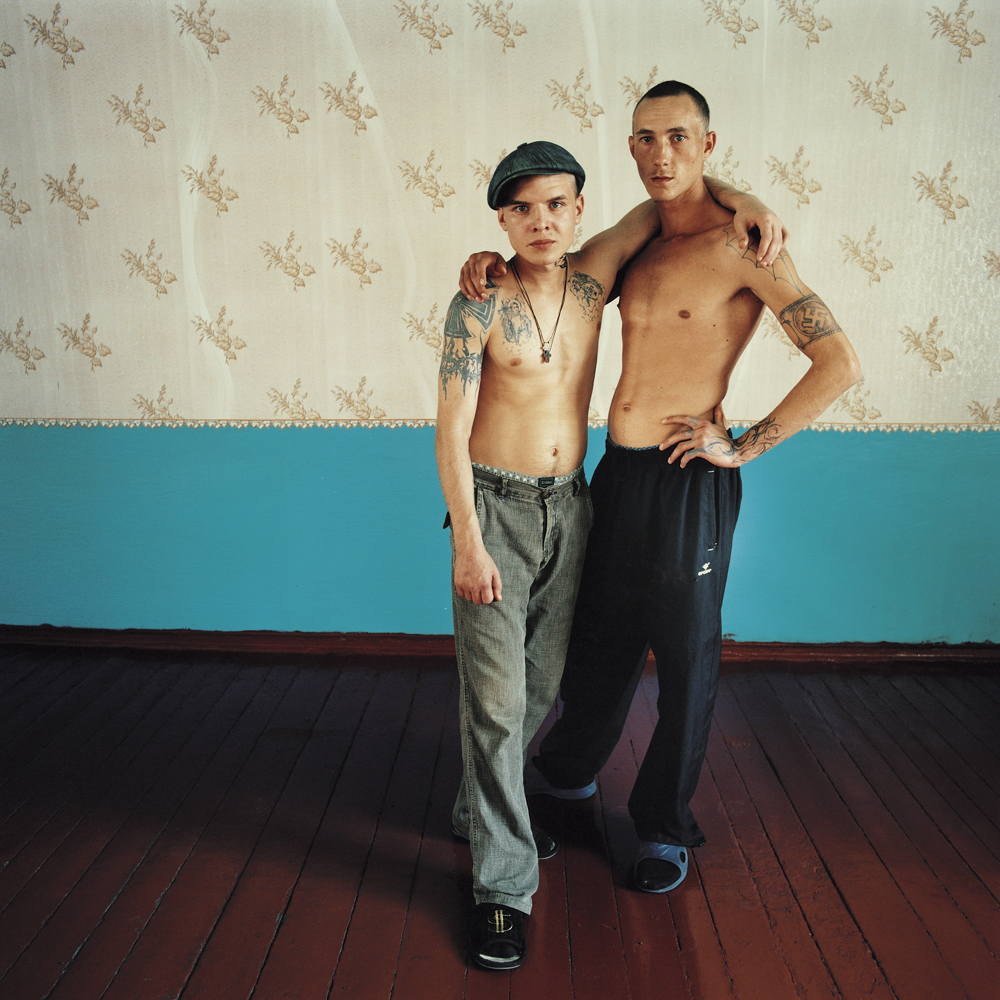

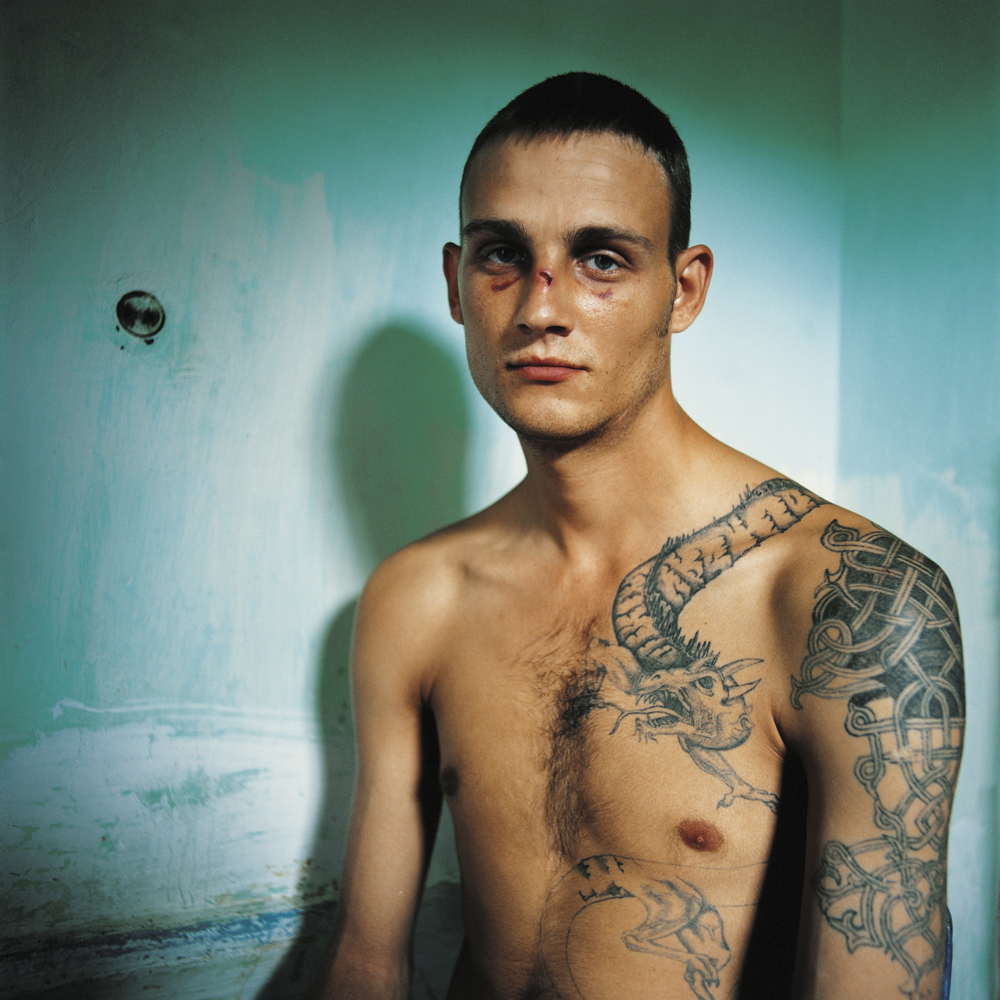

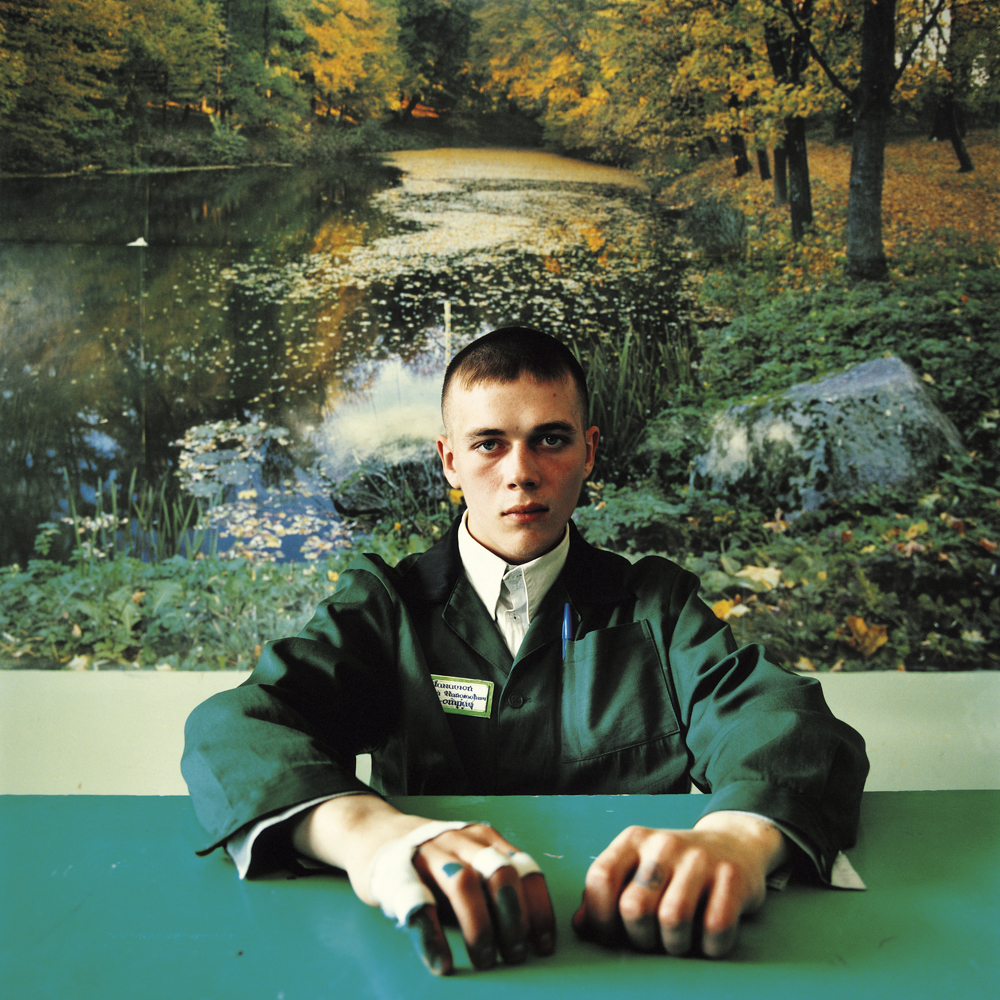

The pair used a network of connections, built over the 10 years they have worked in the region, to gain incredibly rare access to these facilities. What they found inside surprised them. Instead of grey concrete and steel, there were tropical wallpapers, lace-covered tables and furniture painted in glossy blues and greens. The prisoners in Chelbin’s photographs are not dressed in orange jumpsuits, but the floral housedresses, cloth jackets and rubber sandals common to village life in the region. Religious icons seem as ubiquitous as tattoos.

With only one day to work in each location, Chelbin and Plotnizki carefully explored these strange environments, quietly combing halls and common areas to find subjects for their portraits.

“It’s something I look for in their faces, their gaze,” Chelbin said, adding that it was intuition, rather than any specific characteristics, that guided their choices. “It’s not a formula. Some people have this quality that you can’t take them out of your head,” Plotnizki added.

The mood in each location varied widely. Chelbin and Plotnizki described the tense atmosphere of a young boys’ facility as a “living hell, ” while the residents of a men’s prison “were like zombies.”

But it was a prison for women and children in Ukraine that made the greatest emotional impact on Chelbin, who herself had two young children at the time of the shoot. In one frame from that facility, a nursery attendant dressed in white is pictured leaning on the corner of an oversized crib. Inside, toddlers play with rubber balls that mirror the bright, primary colors of a mural painted on wall behind them (slide #7).

The tired, distant expression of the attendant, whose name is Vika, is the only clue that this isn’t a happy scene. The children, we learn from Chelbin, were born in prison and have never known the outside world. Vika herself is a prisoner–charged with murder. She is also a mother, but cannot visit her own child who has been placed in an orphanage.

Chelbin chose not to ask each prisoner about their crimes until after their portrait sessions. Likewise, in the soon-to-be-released book of this work, captions containing the names and criminal charges of each prisoner are left to the last pages. In this way, viewers do not immediately know that a pair of sisters in matching dresses are in custody for violence and theft, or that a young man, reclining on a green iron bed, has been charged with murder.

There are a huge variety of faces in these portraits. There are young girls with pale, delicate skin and older women whose features are made severe with heavy makeup. There are boys so small they look more suited to grade school than prison and men whose scars indicate years of hard living. In all of them, though, there is a sense of dignity.

“I want people to look at the book and see themselves,” said Chelbin. “The circumstances of life could have brought anyone to this place.”

Michal Chelbin is an Israel-based photographer. See more of her work here.

Chelbin’s latest body of work, Sailboats and Swans, will be released on Nov. 1 by Twin Palms Publishers. An exhibition of the work will be on display at the Andrea Meislin Gallery in New York City from Oct. 18 to Dec. 22

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com