An Irish Catholic upbringing contributed to photographer Shannon Taggart’s lifelong interest in the rituals and art of religion. After photographing Spiritualists—people who believe they can communicate with the dead—in upstate New York, Taggart has since been documenting the Haitian religion of Vodou since moving to Brooklyn in 2005.

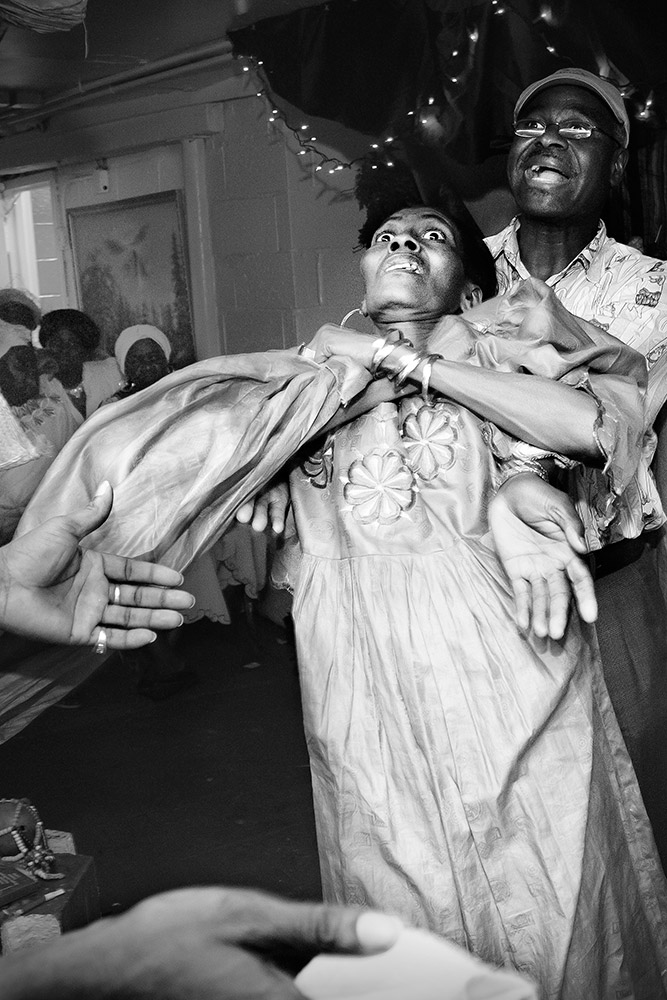

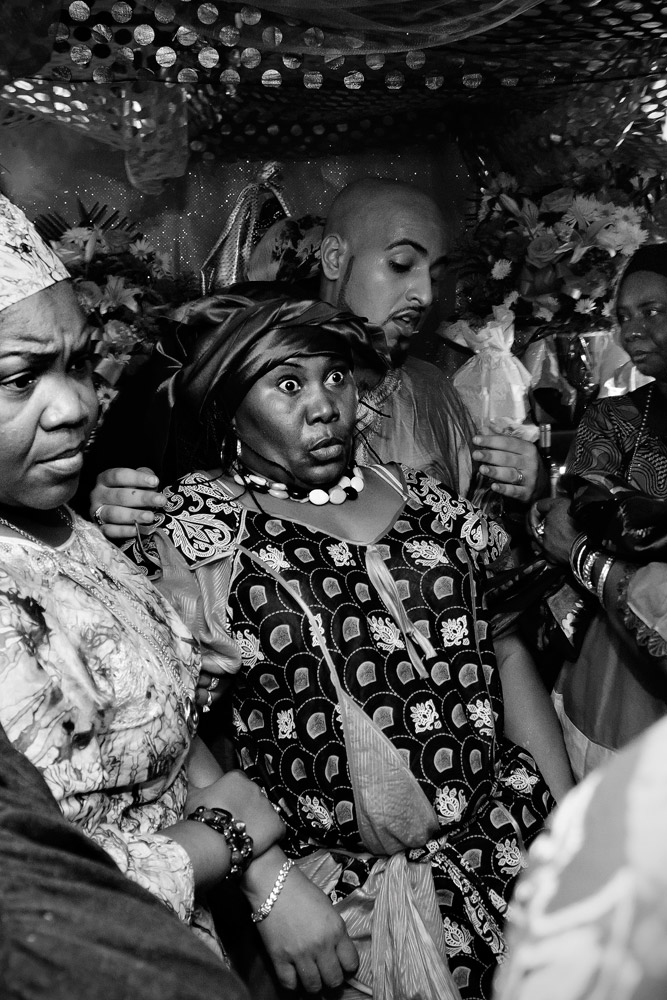

Taggart’s project began when she met a Mambo, or female Vodou priest, named Rose Marie Pierre, who runs a temple in the basement of a nondescript storefront in the working class neighborhood of Flatbush. It was here that Taggart made these images of priests and laymen undergoing possession by the Loa—powerful spirits that act as intermediaries between humankind and Vodou’s distant god, Bondye. Most Loa are benign, some are malevolent, but every spirit has a distinct personality, role in the world and set of demands and services. In their different ways, practitioners believe, these spirits determine our fate and must be consulted and appeased.

Beckoning the Loa requires elaborate preparations unique to the particular spirit desired. Practitioners indicate the Loa they want to call upon by drawing its vever, or symbol, in cornmeal sprinkled on the floor. They place offerings on an altar and perform particular songs and dances. When the Loa possesses the worshiper Taggart says the scene becomes “wild, very physical and intense.” Though she works with black-and-white still images, Taggart is able to convey the noise and energy of these rituals. “There is screaming and thrashing…sometimes [congregants] run around the room as if confused. It can happen suddenly, so it’s often jarring. People immediately gather around the one possessed and assist them with what they need and catch them if they collapse.” Practitioners say the experience induces short-term amnesia; “Mambo Rose Marie is always surprised (sometimes shocked) to see my documentation of what has taken place while she was possessed,” recalls Taggart.

Popular culture often depicts Vodou as dark and menacing, but fails to understand its more unusual elements. One example, animal sacrifice, exists to rejuvenate the Loa after exhausting ceremonies. Taggart says that the chickens, pigs, goats and cows are killed humanely and eaten immediately. In Haiti, where there was no safe way to store meat, the practice provided people with a regular source of safe nourishment, Taggart explained.

Another often misunderstood practice is the presence of weapons in Vodou ceremonies. A man in slide #2 is shown possessed by a warrior spirit named Ogou. He holds a large machete symbolic of that Loa. But as Taggart explains, weapons like these are not used to harm others. Instead, they are relics of Haitian slavery that Vodou practitioners have appropriated as symbols of their faith—much as the cross is a relic of Christian persecution that Christians have turned into a symbol of their faith. These exercises, born of practical and psychological necessity, are far from the spooky behavior that appears so often in film and folklore.

This December, several of these Brooklyn practitioners will undergo a two-week long initiation rite in Haiti. Accompanying them will be Mambo Rose Marie and Taggart, who will photograph the ceremonies. “I don’t know what I will find there, but I am assuming it will be a special experience,” she says.

Shannon Taggart is a Brooklyn-based photographer. See more of her work here.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com