“Yah, but tell me Karon, did you know this Steve Biko?”

The purpose of the question was derisive, an Afrikaans student seeking to silence his uppity liberal classmate’s protests at the brutal murder in prison of a black political activist—the 20th to have been killed behind bars by the policemen enforcing South Africa’s apartheid system in the face of rising tide of black protest. And, of course, everyone in our high school playground huddle that sunny September day knew that I couldn’t possibly have known Steve Biko, or even to have heard of him before his name hit the headlines.

Never mind voices or rights, history or family, black people didn’t even have last names in white South African suburbia in the late 1970s. They were known only by first names easily pronounced by their white employers for purposes of instruction and command. The very presence of black people in white “Group Areas” was not tolerated, under law, except to the extent that they were in servitude to white people as housemaids, gardeners or day laborers. Any black person found on the streets of our neighborhoods who could not prove they were in the employ of a local white family faced arrest by a brutal police force for whom the adjective “racist” would have been redundant, because enforcing a white supremacist racial order was their raison d’etre.

We may have been raised and nurtured by black women, surrogate mothers named Patience or Rachel, but the black people in our world had no last names, never mind voices or opinions. There were no black people as independent actors in our world.

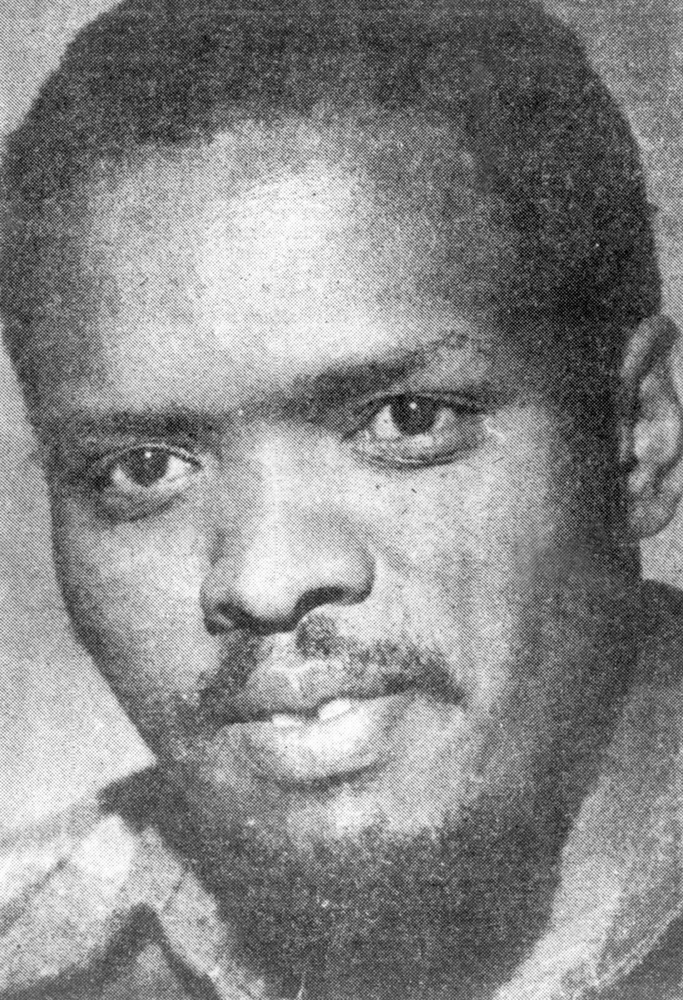

So, no, I did not know, or know of Steve Biko before reports of his death as a result of a savage beating by drunken security policemen made it into our newspapers. I knew nothing of his ideas about how South Africans would one day live together on the basis of equality, judged not by color or ethnicity but simply as individual citizens. I knew nothing of the inspirational work of the brilliant young medical student who had, in the finest traditions of Frantz Fanon and Malcolm X, challenged the psychology of oppression in the minds of black people that allowed white supremacism to keep them down. I knew nothing of his quick wit: Biko was once asked by a white judge in a political show trial, “Why do you people call yourselves black? You look more brown than black.” He shot back, “Why do you call yourselves white? You look more pink than white.”

But I knew apartheid was evil, having watched the regime bulldoze the shacks of peasants driven by rural poverty to settle on the periphery of Cape Town; and having watched on the TV news as the regime’s police shot dead hundreds of black high school students my age, who’d taken to the streets in the Soweto uprising to demand their rights as citizens. We were ordered, during the rebellion, to patrol our school’s grounds at night, lest the black kids – the ones with last names, and very strong opinions, and little patience for racism or patronizing colonial liberalism – came to burn it down. (They never did; if they had, we’d have gladly supplied the matches.)

I didn’t know Steve Biko. But his death made clear to me, and hundreds of young white people like me, what millions of black South Africans knew from experience – that our country’s rulers were not only ignorant racists, but were vicious thugs to boot.

“I am not glad and I am not sorry about Mr. Biko,” Minister of Police Jimmy Kruger told a conference of the ruling party two days after Biko’s death. “It leaves me cold. I can say nothing to you. Any person who dies… I shall also be sorry if I die.” And they laughed. Like B-movie Nazis (which many of them were, having been in youth organizations aligned with Germany during WWII) they erupted in uproarious laughter, cheering on their brandy-and-coke bully boys who had beaten to death a chained captive, in their eyes nothing more than a cheeky “kaffir” (the Afrikaans equivalent of the n-word, curiously enough borrowed from the Arabic for infidel) one who had dared speak back to the white “baas” (master). Even now, it’s hard to hold back the tears of rage that poured freely when I read the detailed account of Biko’s murder.

Biko’s story reached us via the work of Donald Woods, editor of the Daily Dispatch who had the courage to break out of the white suburban bubble and had gotten to know Biko as a friend. And knew him as the leader of the Black Consciousness movement that had captured the imagination of a generation of city-born black youth in South Africa that were not prepared to accept the indignities routinely suffered by their parents. Filling the void left by the banning of the African National Congress a decade earlier and the imprisonment of its leaders such as Nelson Mandela, the BC movement saw itself as leading, in Biko’s words, “the cultural and political revival of an oppressed people”, bringing to South Africa the anti-colonial struggle for liberation that had swept across the continent. Woods, able to see the future in the making, was impressed, eventually earning a banning order and being forced to flee into exile. His editorial on Biko’s death introduced us to the man we would never know:

“My most valued friend, Steve Biko, has died in detention. He needs no tributes from me. He never did. He was a special and extraordinary man who at the age of 30 had already acquired a towering status in the hearts and minds of countless thousands of young blacks throughout the length and breadth of South Africa.

In the three years that I grew to know him my conviction never wavered that this was the most important political leader in the entire country, and quite simply the greatest man I have ever had the privilege to know.

Wisdom, humour, compassion, understanding, brilliancy of intellect, unselfishness, modesty, courage—he had all these attributes… The government quite clearly never understood the extent to which Steve Biko was a man of peace. He was militant in standing up for his principles, yes, but his abiding goal was a peaceful reconciliation of all South Africans.”

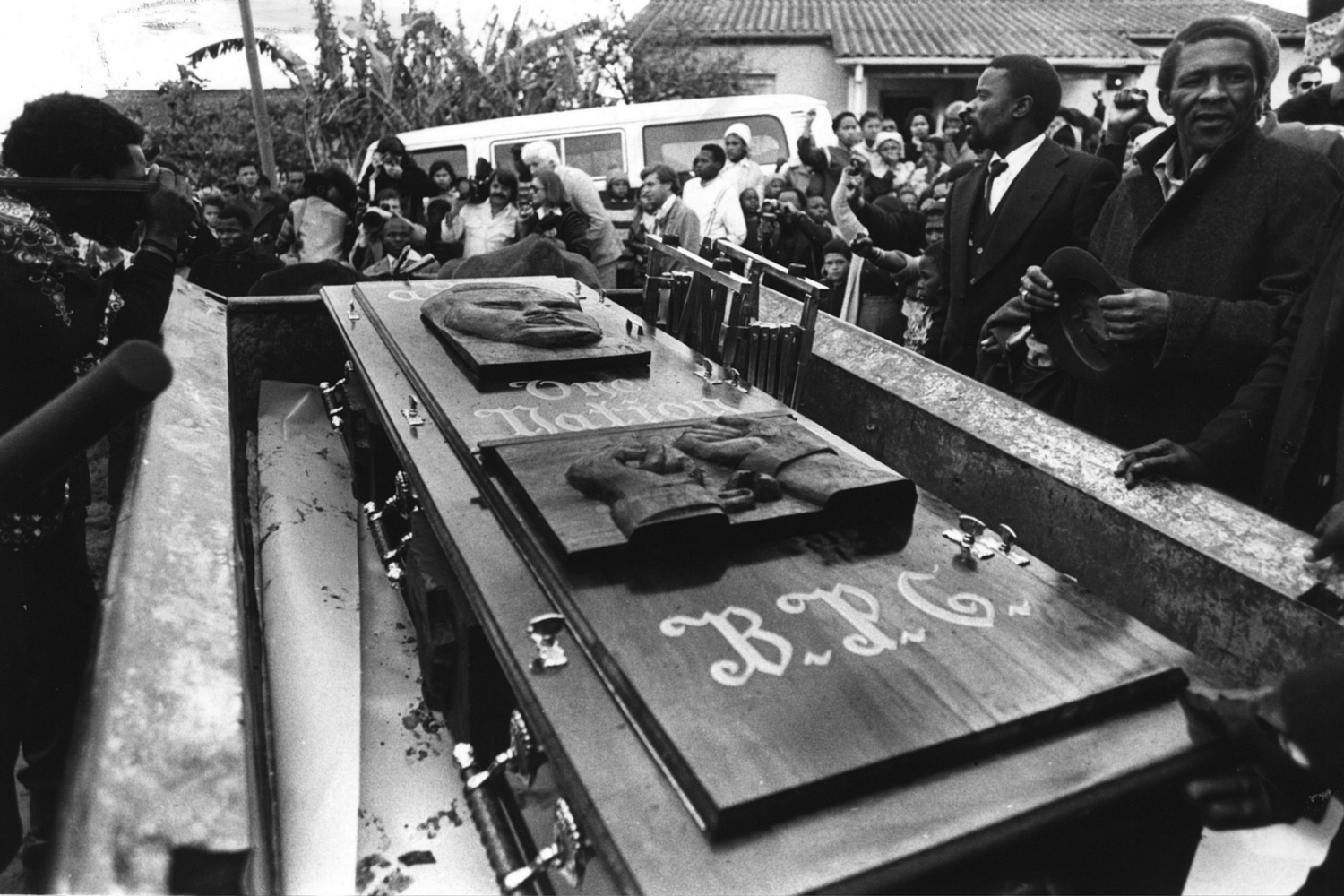

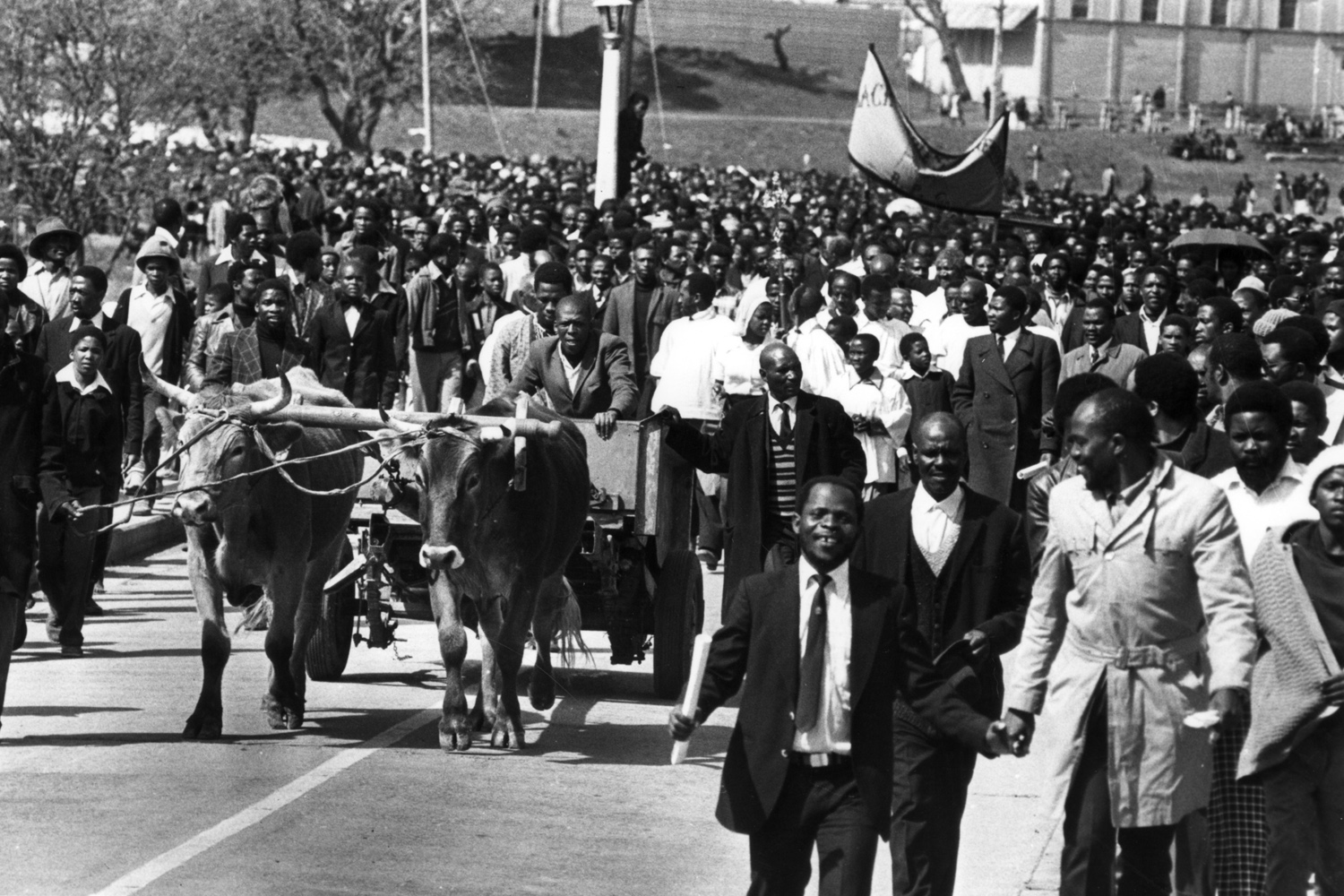

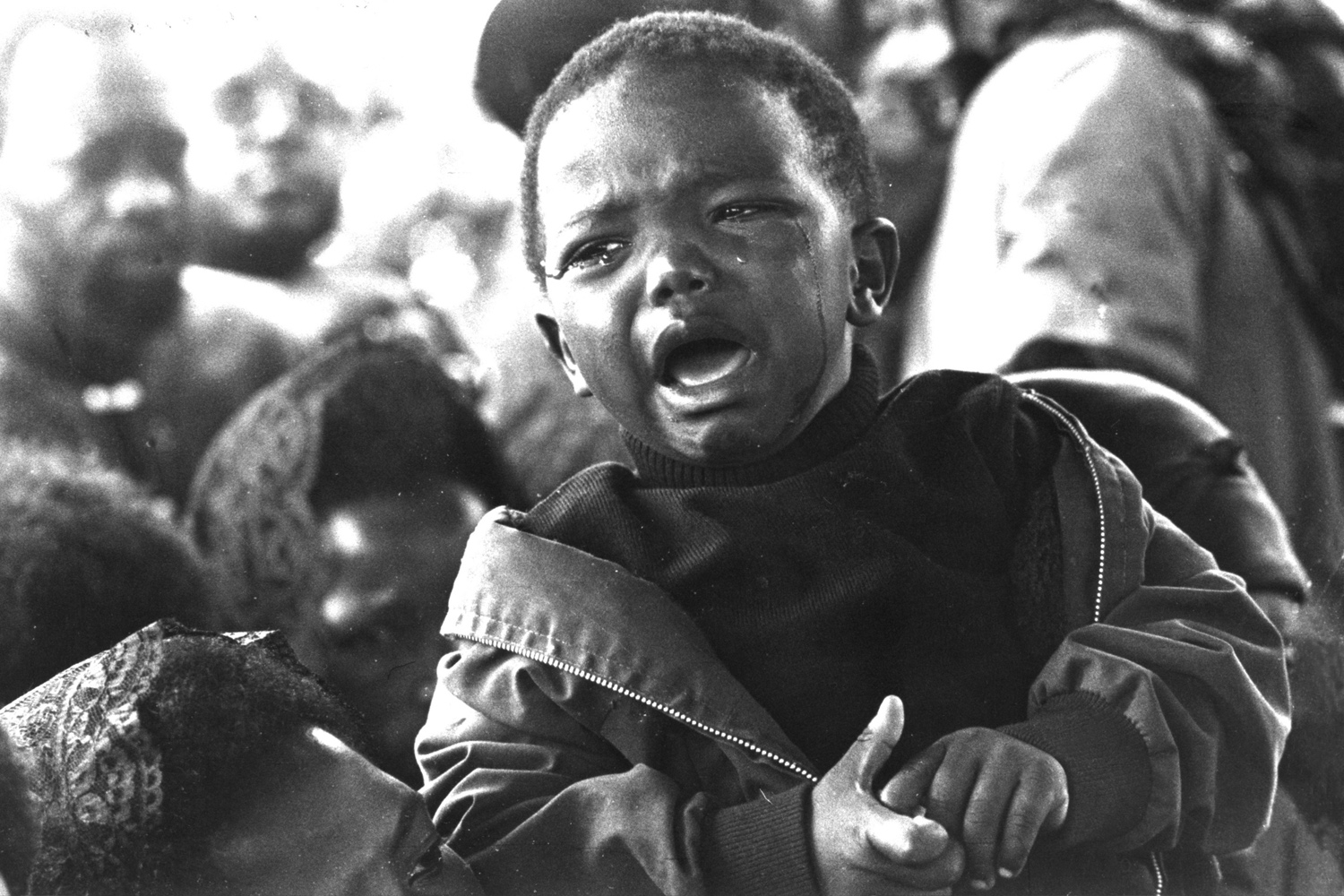

Biko’s funeral service was led by then Bishop Desmond Tutu, an Anglican cleric whose unwavering willingness to speak truth to power earned him a Nobel Peace Prize and still, today, marks him as a unique voice for justice in South Africa. It was a fitting tribute, even if many thousands of those who tried to reach the event were prevented from getting there by the cops, many of them dragged off buses and brutalized.

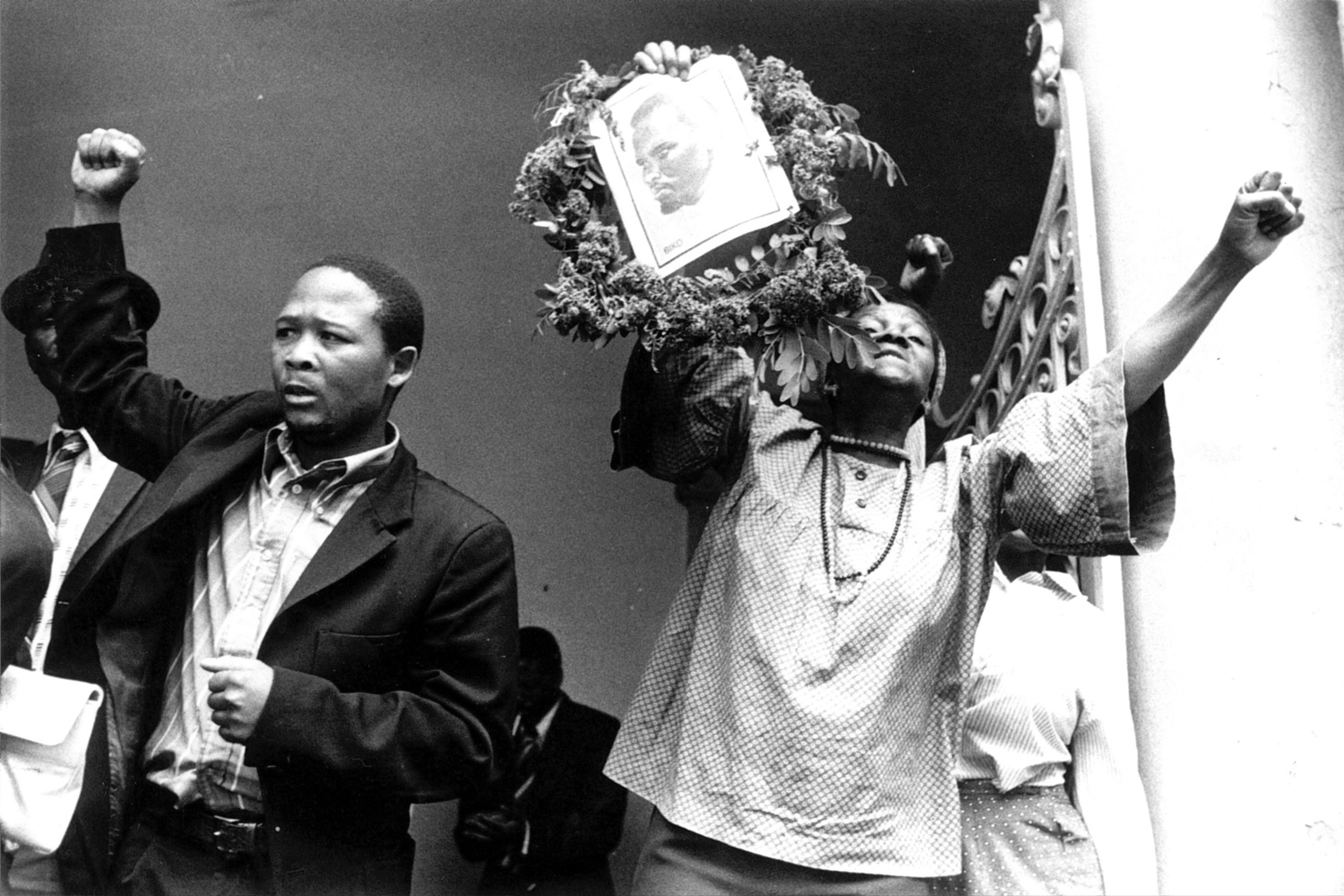

Still, Biko’s burial was an impressive send off, some 15,000 voices joined as once in chants of “Amandla! Ngawethu!” (Power is ours!) signifying the dawning recognition that black collective action would make apartheid untenable.

That spectacle was supposed to terrify me, sitting in my white suburban ghetto. But in light of Biko’s murder, and the massacre of protesting students the year before, I burned with a mounting—if, at that stage, impotent—rage at the racist brutality being unleashed in my name. Instead of scaring me, the idea of thousands of young black people armed with nothing but the stones in their hands and the courage in their hearts standing up to Jimmy Kruger and his thugs filled me with hope that justice would be done—and that I would see the birth of a different South Africa. Two years later, I arrived at the University of Cape Town, our portal from white suburbia into the wider, black-led political struggle.

There I finally “met” Steve Biko, through his writings, equal parts rage, humanity, profound insight and the irrepressible humor common to the truly brilliant political communicators. As we marched around our campus demanding freedom for Nelson Mandela and later, as we joined the ANC and its allied organizations fighting to end the monstrous system of apartheid, we were beginning, in our own tiny way to build the country that Steve Biko died fighting for, 35 years ago today. The fight to end apartheid had claimed many thousands of lives before his, and many thousands more would be killed after Biko’s murder. But no death shook my world, and the country all around me, more than Steve Biko’s. He lives on in the best achievements of the South Africa he helped birth, and in the best instincts of those who continue to challenge its flaws.

Tony Karon is a senior editor at TIME. A native of South Africa, he now resides in New York.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com