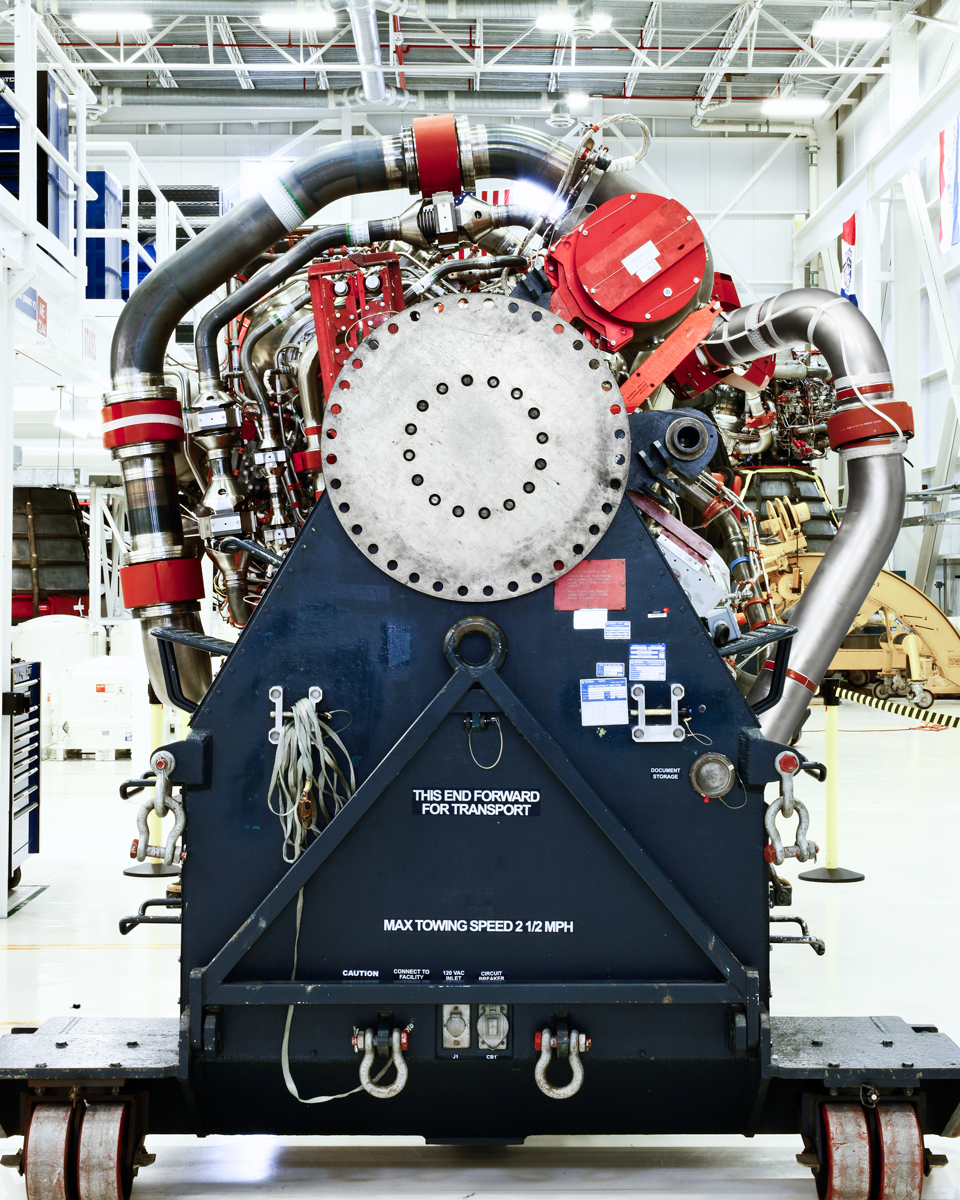

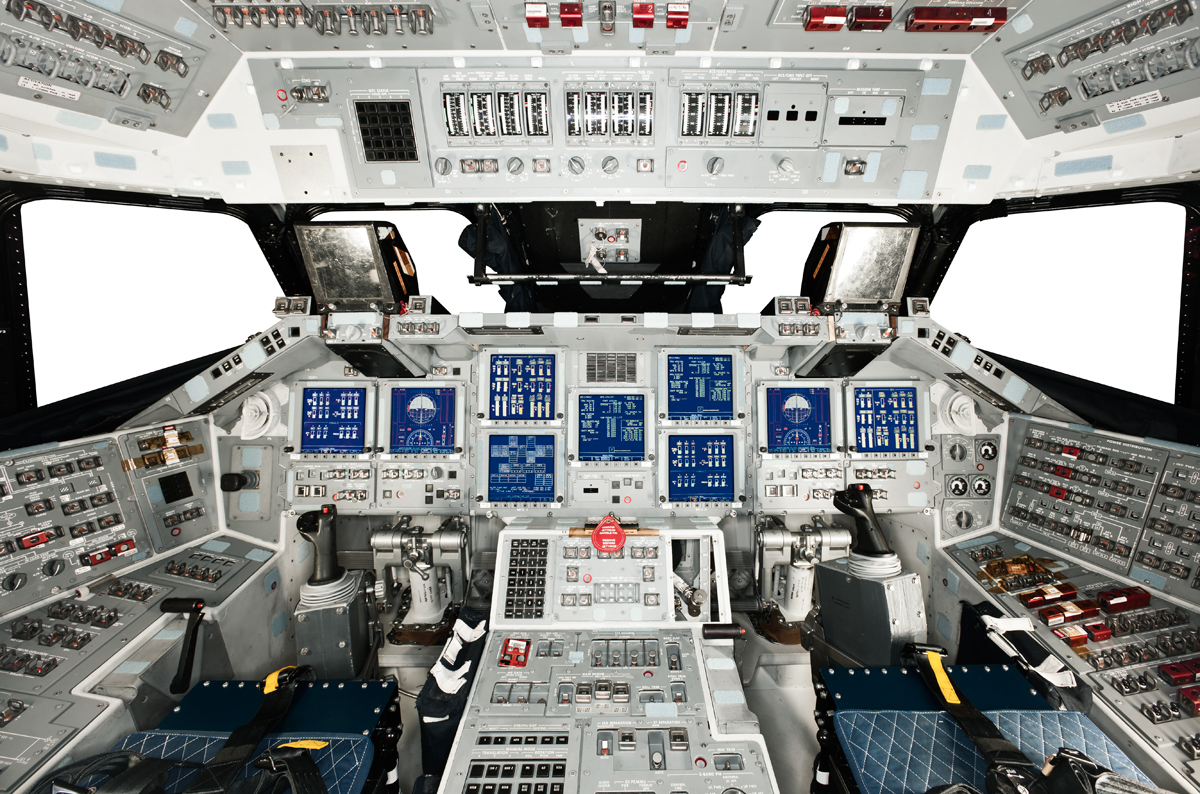

All space missions begin in violence. Traveling through the cosmic void may be a smooth and utterly silent thing, but getting off the ground in the first place is a feat achieved only with massive engines, silos of fuel and the controlled explosions they’re designed to produce. Those explosions can do a lot of damage, which is why no one—save the astronauts themselves, who willingly climb inside all that erupting hardware—have ever been allowed to get anywhere near a rocket when it’s taking off. That fact can be murder on the business of launch pad photography.

It’s one of the great ironies of journalism that it’s a lot easier to capture close-up images of the murderous business of war than of the peaceable work of putting people and payloads in space. But the rules are as strict as they are extreme: On launch days, rockets sit at the middle of a circular evacuation zone that, in the case of the space shuttles and the old Saturn V’s, stretched up to three miles in all directions. That no-go rule has never diminished the demand for arm’s-length images of the liftoffs—and satisfying that demand has called for some creative thinking, engineering and camera-rigging on the part of the people taking the pictures.

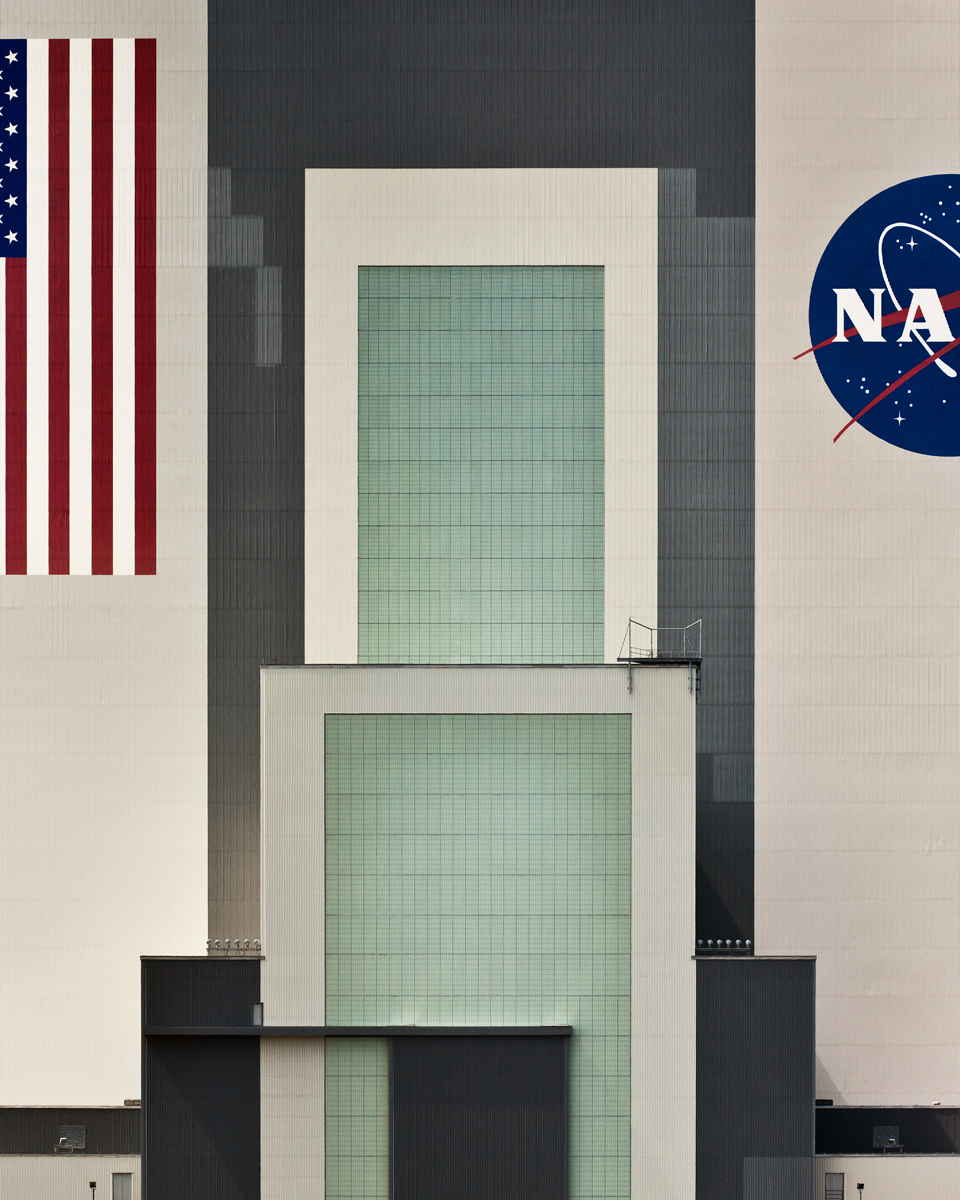

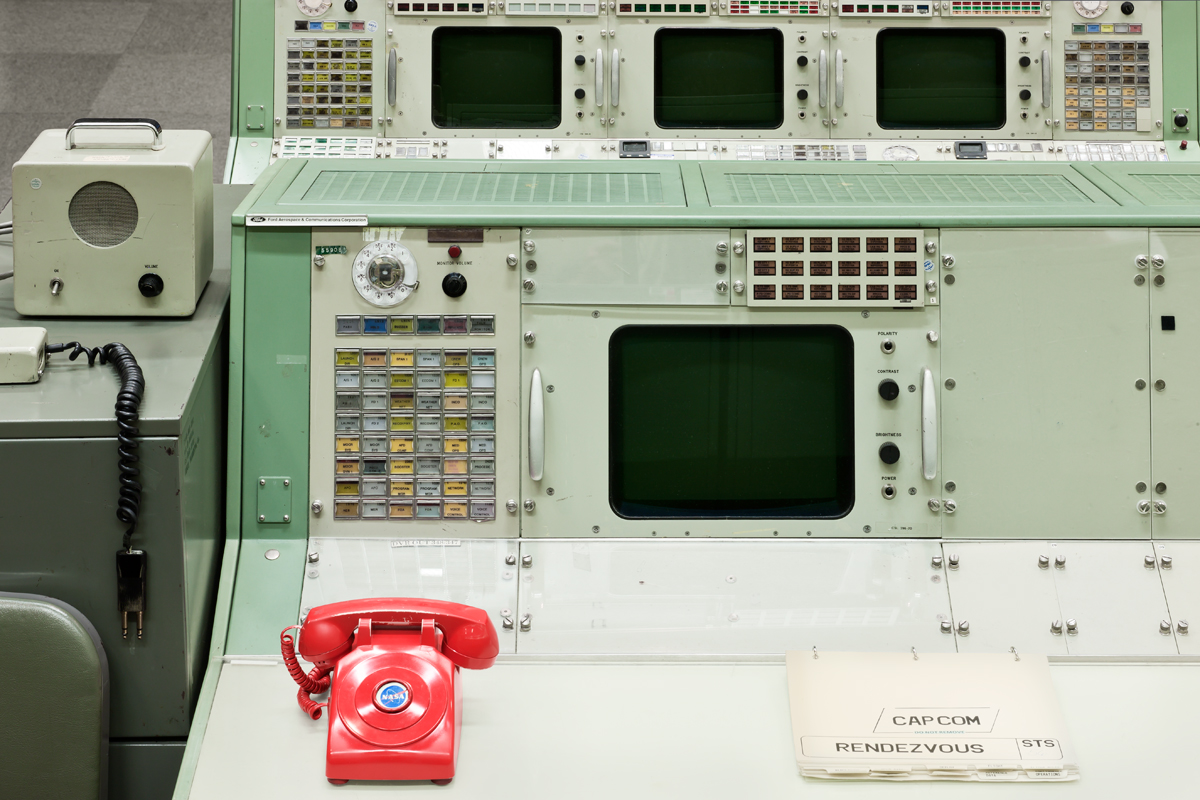

Dan Winters, who grew up during the golden age—the Cronkite Age—of space reporting, is one of the photographers who has mastered the craft best. As the images that follow—taken from his new book, Last Launch—show, he has proven himself a virtuoso at his work. His pictures can practically singe your eyebrows and set you squinting with their brilliance, while at the same time capturing the black smoke and deep clouds that are often the counterpoint to the fires of liftoff.

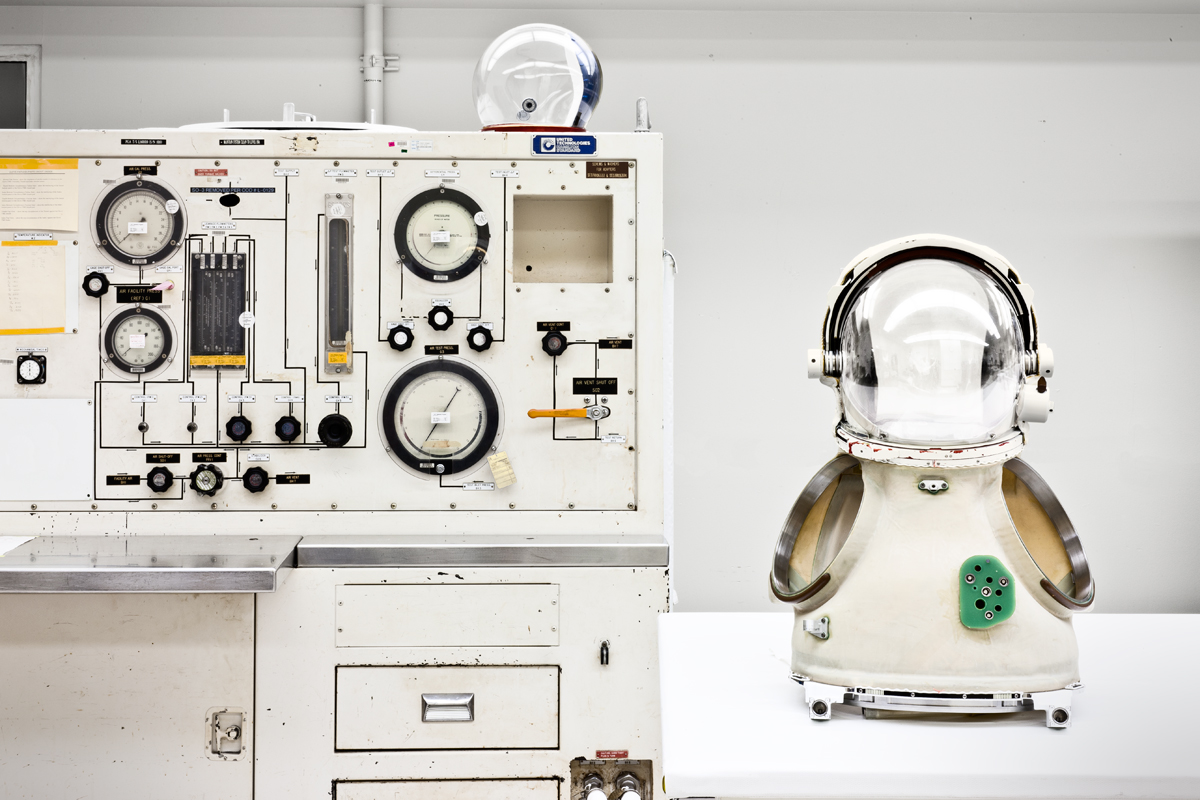

The work begins the day before launch, when he positions up to nine cameras as little as 700 ft. (213 m) away from the pad. Each camera is manually focused and set for the particular shot it is meant to capture, and the wheels of the lens are then taped into position so that they can’t be shaken out of focus when the engines are lit. Electronic triggers—of Winters’ own devising—that do react to the vibrations are attached to the cameras so that the shutter will start snapping the instant ignition occurs.

To prevent the cameras from tipping over on their tripods, Winters drills anchoring posts deep into the soil and attaches the tripods to them with the same tie-down straps truckers use to secure their loads. He also braces each leg of the tripod with 50-lb. (23 kg) sandbags to minimize vibration. Waterproof tarps protect the whole assembly until launch day, when they are removed and the cameras are armed. Throughout the launch, they fire at up to five frames per second. Only after the vehicle has vanished into the sky and the pad crew has inspected the area for brushfires, toxic residue and other dangers, are the photographers allowed to recover their equipment.

Earlier in his career, Winters, like all photographers, shot with traditional film. “Back then,” he says, “after shooting … there was still the wait until the film was actually processed—which seemed like an eternity.” For the three liftoffs in Winters’ book, including STS-135, the 2011 launch of the Atlantis that was the last ever shuttle flight, he used digital equipment.

The shuttles have now been mothballed, never to fly again. Other, unmanned rockets are already flying and other American astronauts will surely go aloft from Cape Canaveral before too many years have gone by. But until then, the old shuttles endure in images like Winters’—which will prove to be far more permanent than the great machines themselves.

Last Launch will be available through the University of Texas Press in October, 2012.

Dan Winters is an award-winning photographer based in Austin, Los Angeles and Savannah. Winters recently photographed the cover for TIME’s military suicides story. Previously, TIME assigned Winters to shoot The Last Liftoff: A Farewell to the Shuttle Program.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Biden Dropped Out

- Ukraine’s Plan to Survive Trump

- The Rise of a New Kind of Parenting Guru

- The Chaos and Commotion of the RNC in Photos

- Why We All Have a Stake in Twisters’ Success

- 8 Eating Habits That Actually Improve Your Sleep

- Welcome to the Noah Lyles Olympics

- Get Our Paris Olympics Newsletter in Your Inbox

Write to Jeffrey Kluger at jeffrey.kluger@time.com