For two years, Sergeant Major Pat Corcoran had no recollection of the most important week of his life. On Aug. 13, 2009, Corcoran was on a patrol in eastern Afghanistan. He had just finished checking on his troops on the ground, who were clearing the sides of a roadway for hidden bombs, when he climbed into his armored vehicle, buckled his harness and told his driver to move out. A second later, a bomb erupted right underneath Corcoran’s seat; he woke up a week later in Germany.

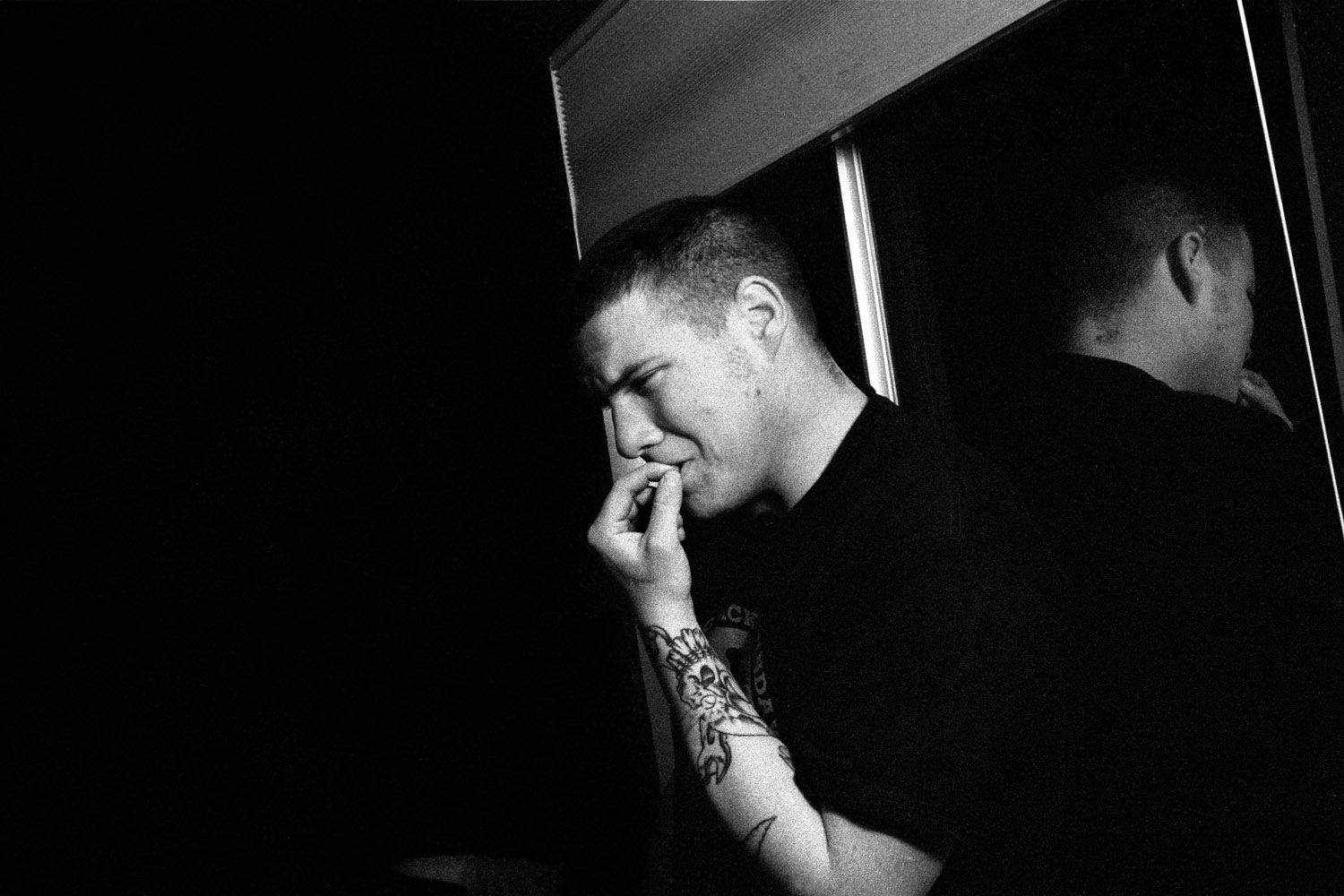

Sergeant Corcoran discusses his journey to recovery after being injured in Afghanistan.

During those missing days, many people worked furiously to keep Corcoran alive: his soldiers dragged him from the upside-down vehicle, and combat medics tried to stabilize his injuries; a flight crew working with the 8th Forward Surgical Team (FST) in Logar Province flew to the scene of the blast and ferried him away. Once Corcoran made it to the FST headquarters–a trauma center close to the battlefield–the doctors and nurses from the 8th FST labored for more than eight hours to stabilize his injuries. The blast broke Corcoran’s legs and pelvis; a piece of the roadway, under which the bomb had been buried, hit him just below his body armor vest; his spinal cord was also broken, and midway through that chaotic day, the medical team learned he would be paralyzed.

Corcoran might never have learned about those heroic efforts to save his life were it not for photographer Erin Trieb, who was embedded with the 8th FST. When the call came over the radio about casualties from an Improvised Explosive Device, Trieb grabbed her camera and hopped on the helicopter. While flight medics worked to keep Corcoran alive during the flight, she photographed their work in the cramped helicopter cabin, then kept shooting in the trauma center, marveling at how the medics, nurses and doctors had the drill down to an exact science. “It was like watching a symphony being conducted—they knew their jobs so well,” Trieb says.

As soon as Corcoran arrived, it was clear he was different from most of the patients they’d seen: young soldiers, most in their early 20s. Corcoran was one of very few sergeants major to be wounded during Trieb’s time with the FST, and he was one of the most severely wounded of all the casualties. They found out he had been set to retire in less than six months after 24 years of service, and that he had young children at home. “He was so close to dying several times, it was up and down emotions the entire day,” Trieb says. “It took a very long time to stabilize him. As soon as the doctors and nurses would stabilize him, something would happen.”

Once Corcoran was finally stable enough to be moved, the flight team took him to Bagram Airfield, then he was flown to Germany for more extensive surgeries. Trieb, meanwhile, set to the task of organizing the shots that emerged from the day’s chaos. “It’s a very strange process,” she says. “You’re looking at pictures of someone basically almost dying and you’re like, ‘Which one looks better?’ You’re trying to do your job and I don’t think any of that hits you until much after the fact.”

While Trieb finished her embed in Afghanistan, Corcoran began his long journey home. In Germany, he developed an ileus, a condition where his abdomen filled with fluid, and an infection raged through his body. Doctors wanted to fuse his broken spinal cord, but feared he would die during such an extended surgery. So they flew him to the U.S., where he spent six weeks in the intensive care unit at Walter Reed hospital before doctors were able to repair his spinal cord during several more surgeries.

About two months after Corcoran was wounded, Trieb sent him some of her photographs. Then in April this year, she traveled to Florida to meet Corcoran for the first time. After months of living in hospitals, Corcoran and his family moved into a house designed for wounded warriors. Trieb showed him the photographs from the day of his injury and filled him in on the frantic hours after the bomb blast. “I was absolutely amazed to see them,” Corcoran says. “All of these dark visions, those began to get filled in. There’s so much that I don’t know. Come to find out, she knew, and remarkably had photographs of it all. Most people would be disturbed by that. I was elated, to say the least.”

Trieb also photographed Corcoran’s physical therapy as he continued to work to gain strength and fully recover nearly two years after being wounded. “These injuries don’t just stop because the soldier is home,” Pat’s wife, Becky, says. “These are life-long injuries that will never go away.” Trieb’s photographs of Pat’s therapy will be added to a growing collection for The Homecoming Project, a non-profit organization Trieb started that uses visual storytelling to illuminate the ongoing issues of veterans from the past decades’ wars.

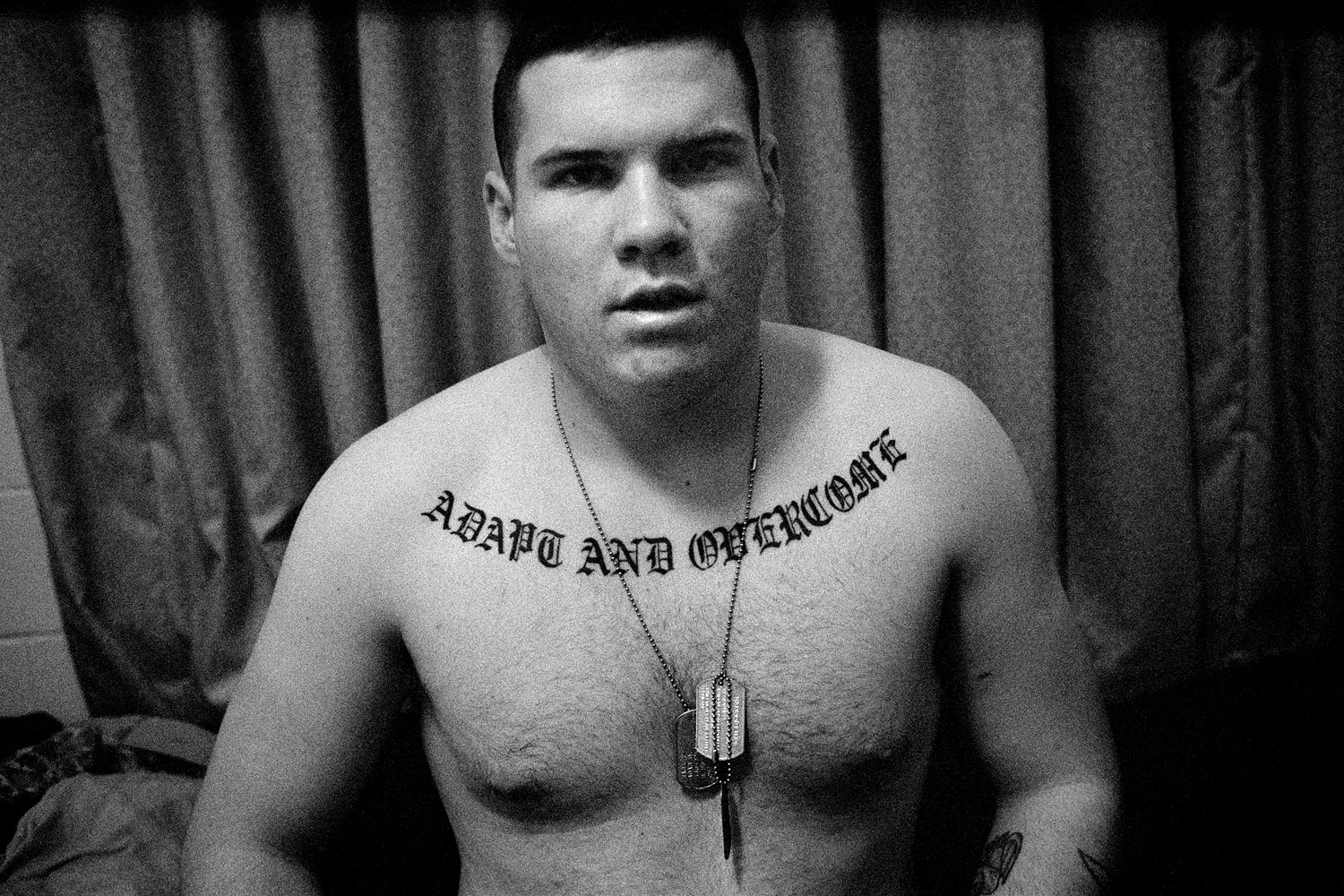

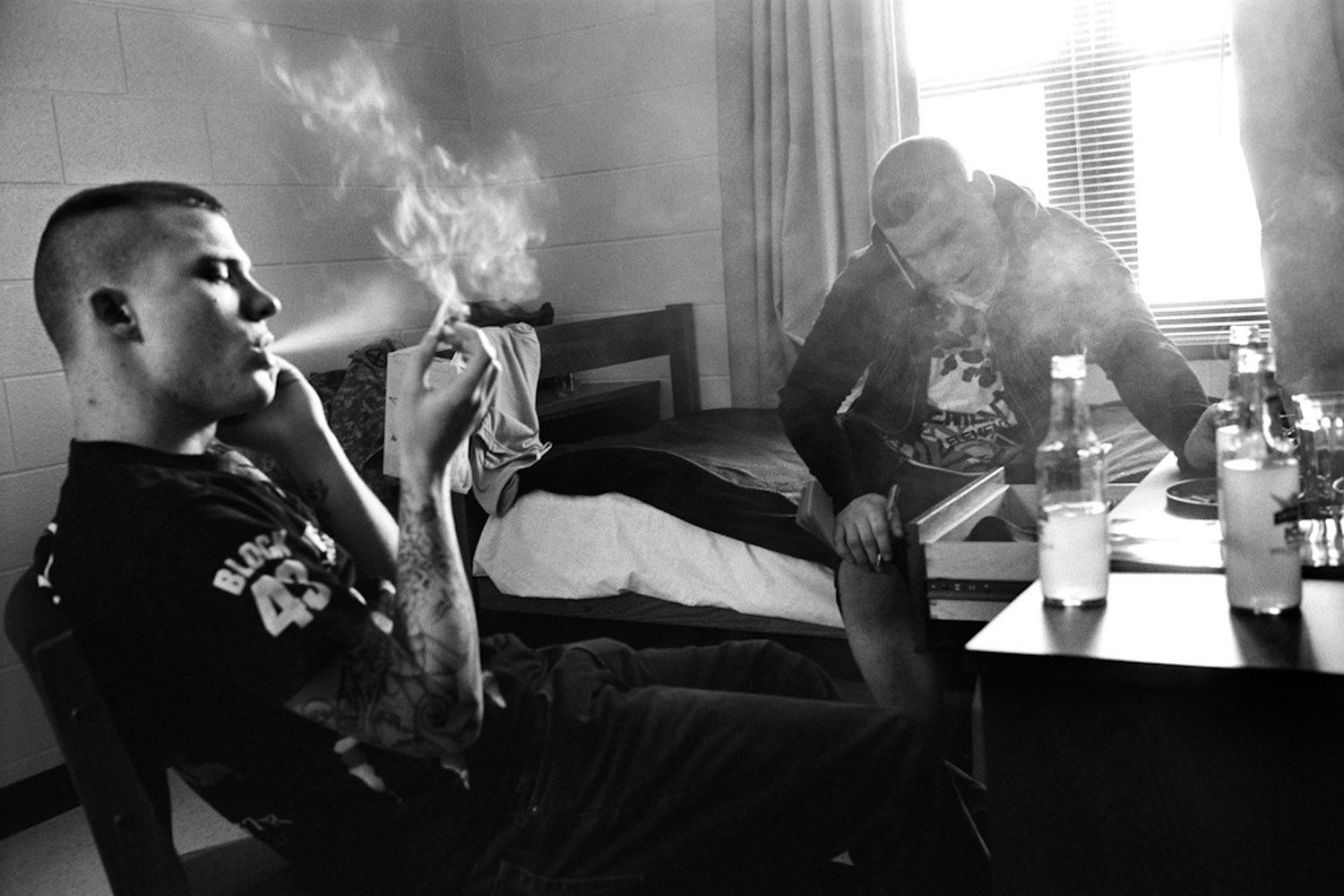

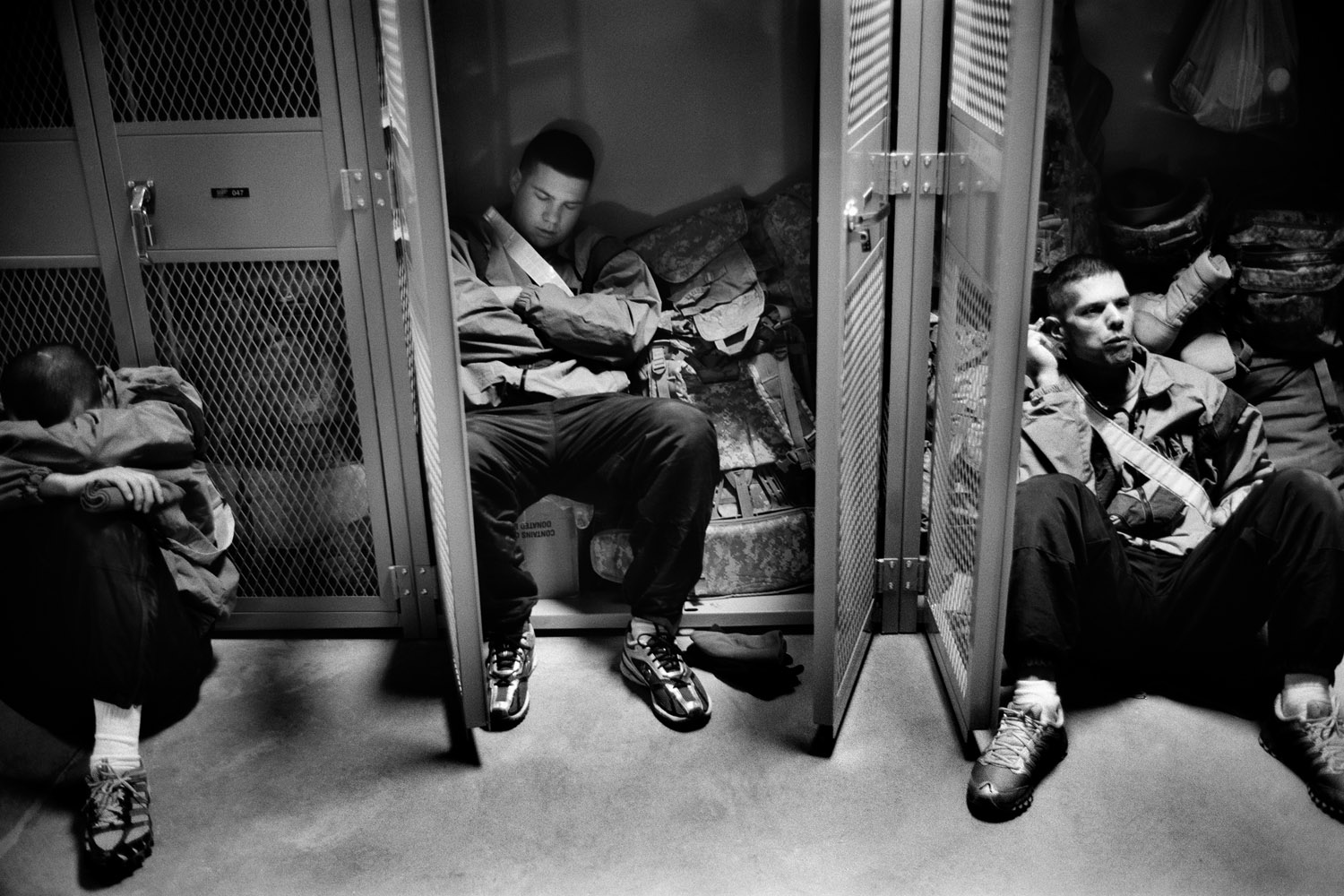

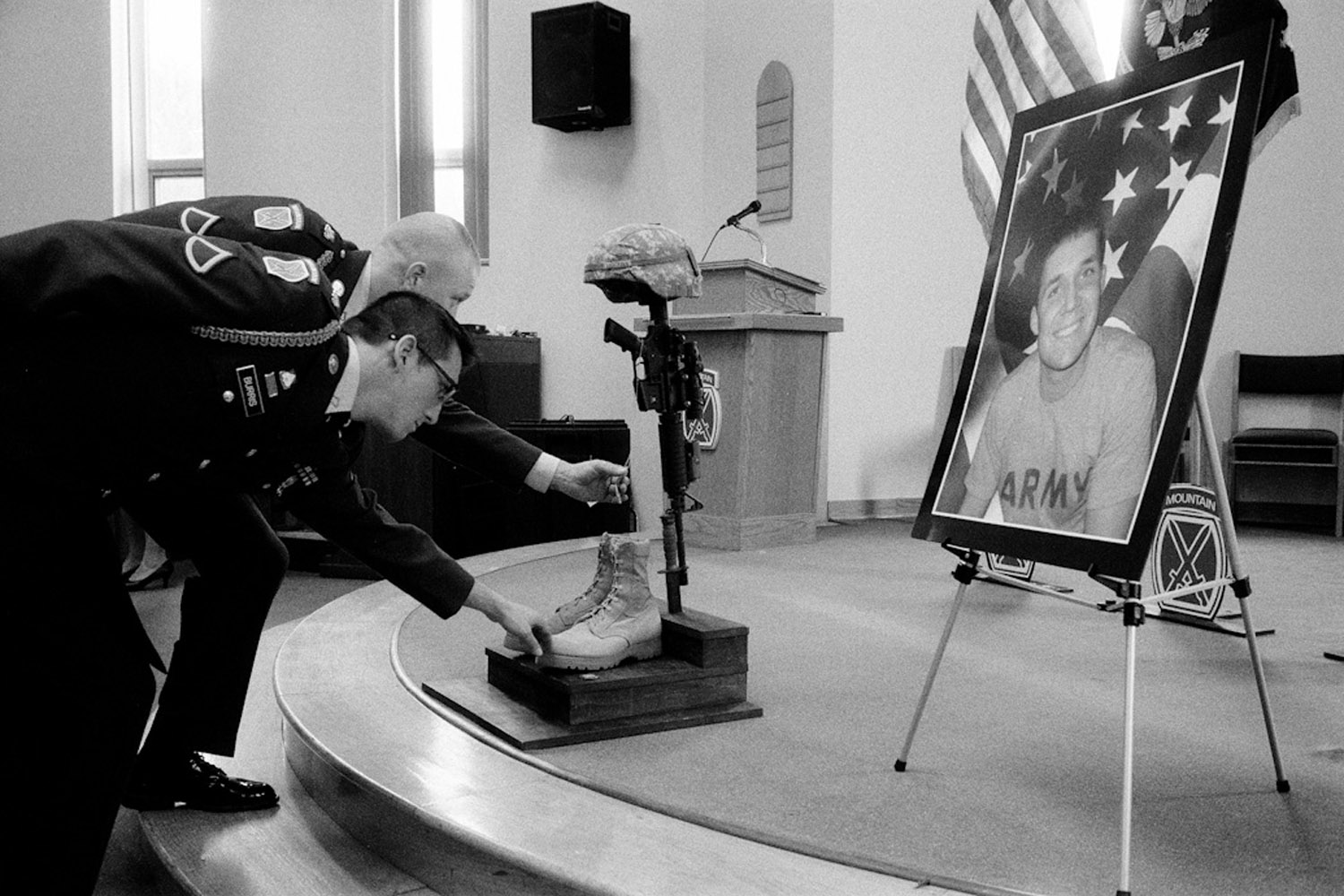

The Homecoming Project, which began when Trieb spent months with soldiers from the 10th Mountain Division after their return from Afghanistan, documents the struggles many troops face when they return home from combat. “Somehow, we’ve got to have a conversation about these two wars in a way that’s palpable for the public and in a way that they’re not burned out seeing or hearing it,” Trieb says. “It’s been too long and I feel like it doesn’t even faze them. It’s my job to be a journalist and report, but ultimately it’s my passion to reach the public in a really meaningful way.” It is a mission that Corcoran is proud to support with his own story. “I couldn’t be more proud of her and organizations like that,” Pat says. “I was tickled to death to be able to meet her and have some common understanding about this whole thing. She’ll go a long way with that work.”

Erin Trieb is an Austin-based photographer. See more of her work on her website and learn more about The Homecoming Project here.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com