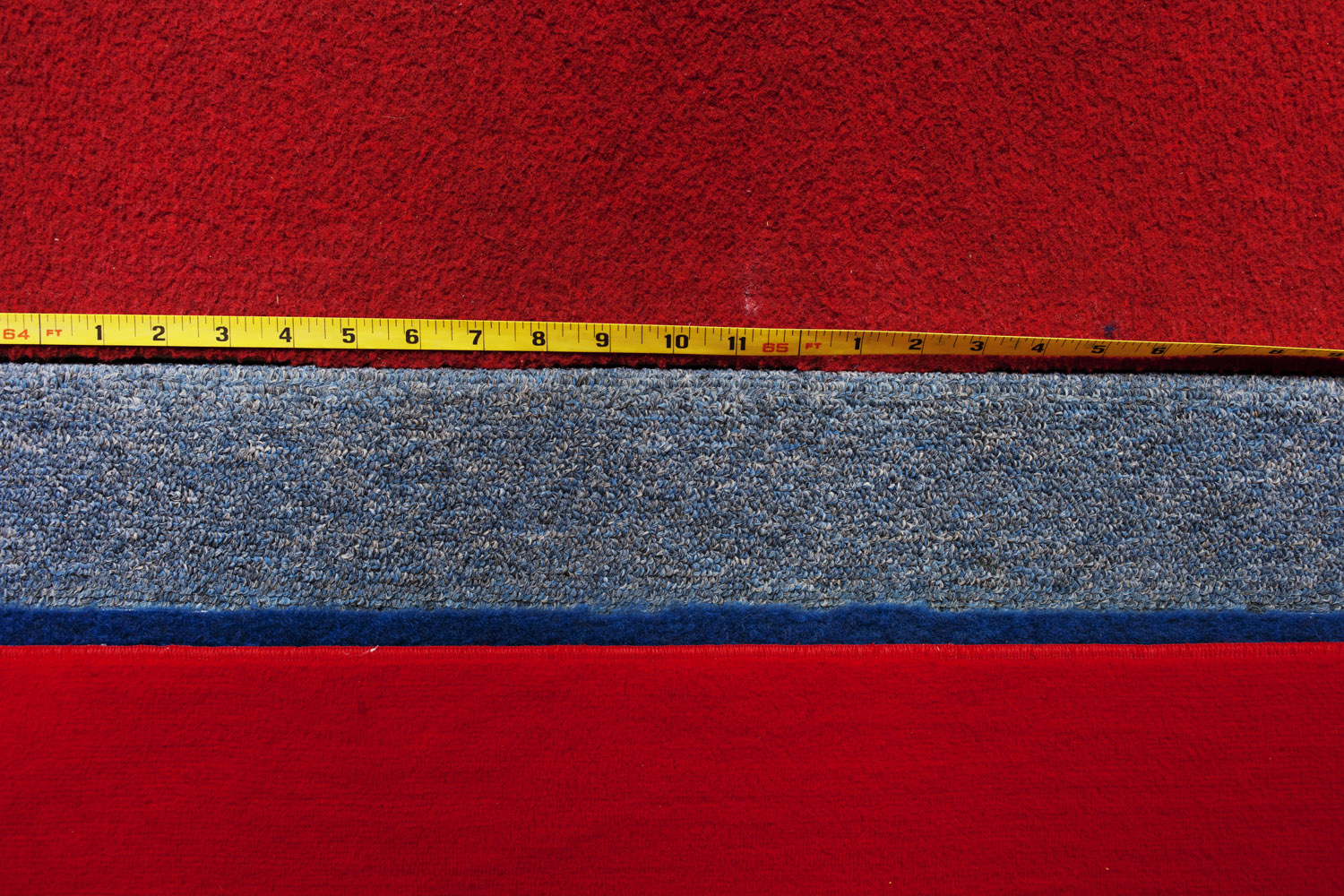

The girls aren’t here but their presence lingers everywhere —their images hang in larger than life posters that cover the walls — Olympic and world champions, frozen in fierce, mid-competition poses — their chalky white footprints cover the mats that litter the gym floor, tracing the crazy circuits of routine after routine performed here at the U.S. Gymnastics’ National Training Center. The chalky dust that anchors tiny gymnasts to their precarious apparatus cakes their calloused hands, too, and is shed in ghostly prints on the 4-inch balance beam, on the uneven bars that loom 8 feet off the ground, and even on the rest room door. That might be the dusty legacy of where the reigning Olympic all-around champion jumped onto the beam; those could be the footprints of the country’s best gymnast on the uneven bars; that might be where the world vault champion stuck a difficult landing.

(For TIME’s daily coverage of the 2012 Games, visit: Time.com/Olympics)

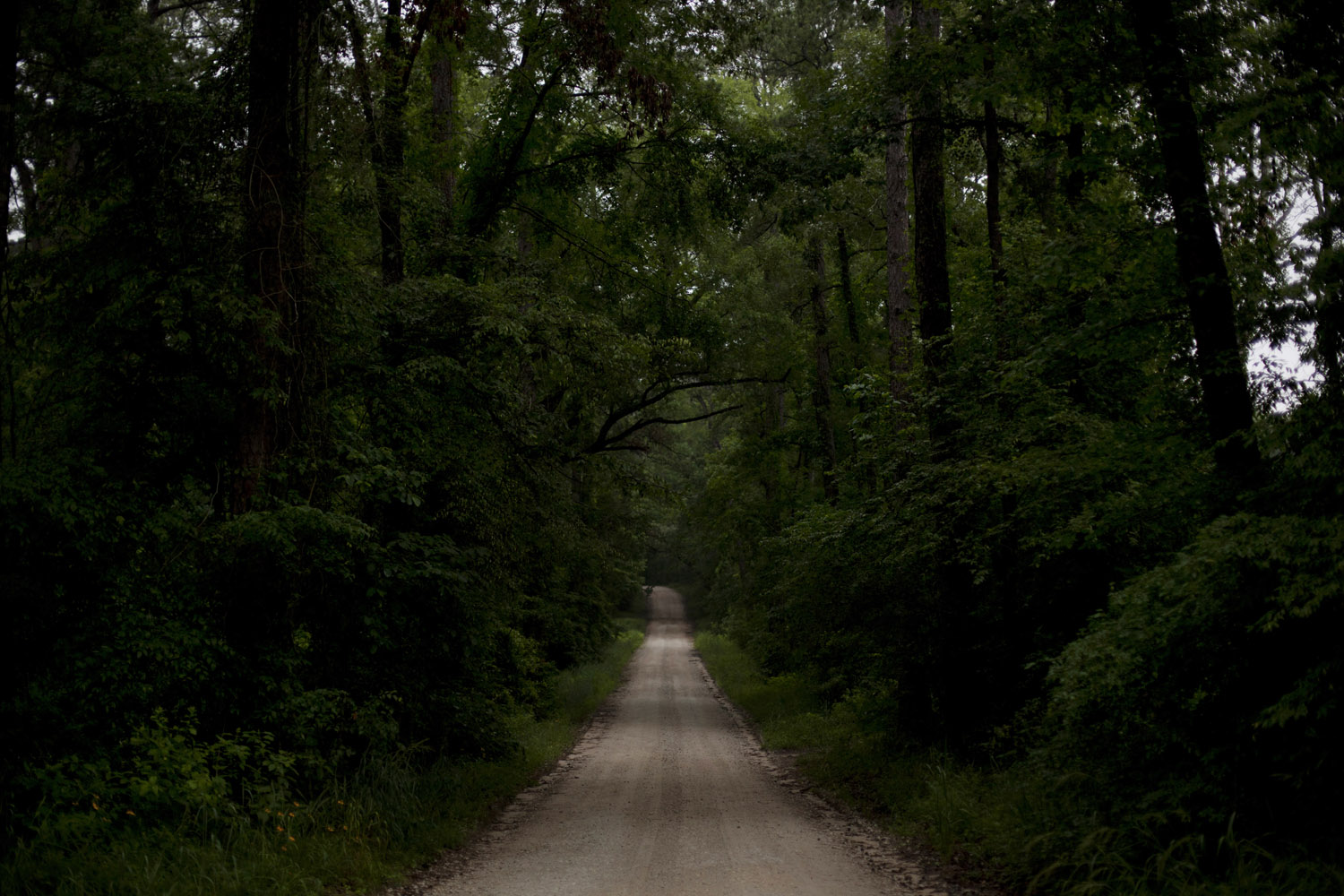

This is where every girl who wants to be an elite gymnast must come, at some point in her career, to pay tithings, in the form of blood, sweat, and often tears, to Martha Karolyi. This is where every gymnast with Olympic dreams earns the right to represent the U.S. and wear the coveted team leotard. This is where Karolyi puts the girls to the test, once a month, for four strenuous days. It’s called training camp, and while there are bunk beds and the shared cabins and bucolic surroundings deep in the woods of New Waverly, Tex. — complete with lakes and boats and tennis courts and a pool — it’s nothing like the care-free summer excursions that most of us know.

“I make it very clear for the girls, they come here for one single reason, that’s to train,” says Karolyi in her sharp, Hungarian-inflected English.

The remoteness of the location is actually an advantage, at least in Karolyi’s eyes. A 30 to 40 minute drive from Houston, reached after a nearly 10 minute ride along a dirt road that winds through forest where deer and wild boars roam, the training center is the focal point of the Karolyis’ 3000 acre ranch. For the girls, making the pilgrimage here has but one purpose — to impress Karolyi. While a selection committee that includes Karolyi, a USA Gymnastics representative and an athlete representative determines the Olympic team, everyone — coaches and gymnasts alike — knows that the person with the strongest voice is Karolyi. “She is the big lady,” says Shawn Johnson, the Olympic all-around silver medalist in Beijing. And the way to Karolyi’s heart? Nothing short of perfection. “We strive for perfection. I state that every moment when I have a chance,” she says. “If that is not your goal, then you are in the wrong place.”

Read more about the USA Gymnastics training center and the Karolyis here.

Alice Park is a staff writer for TIME covering health and medicine.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- How Far Trump Would Go

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- Saving Seconds Is Better Than Hours

- Why Your Breakfast Should Start with a Vegetable

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- Welcome to the Golden Age of Ryan Gosling

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com