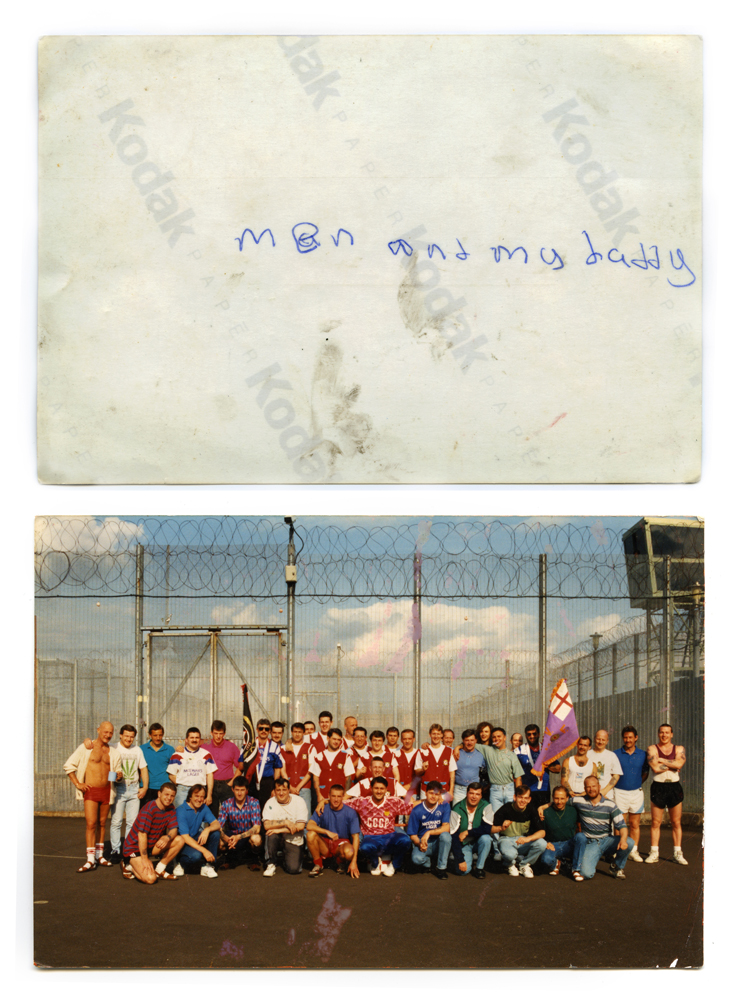

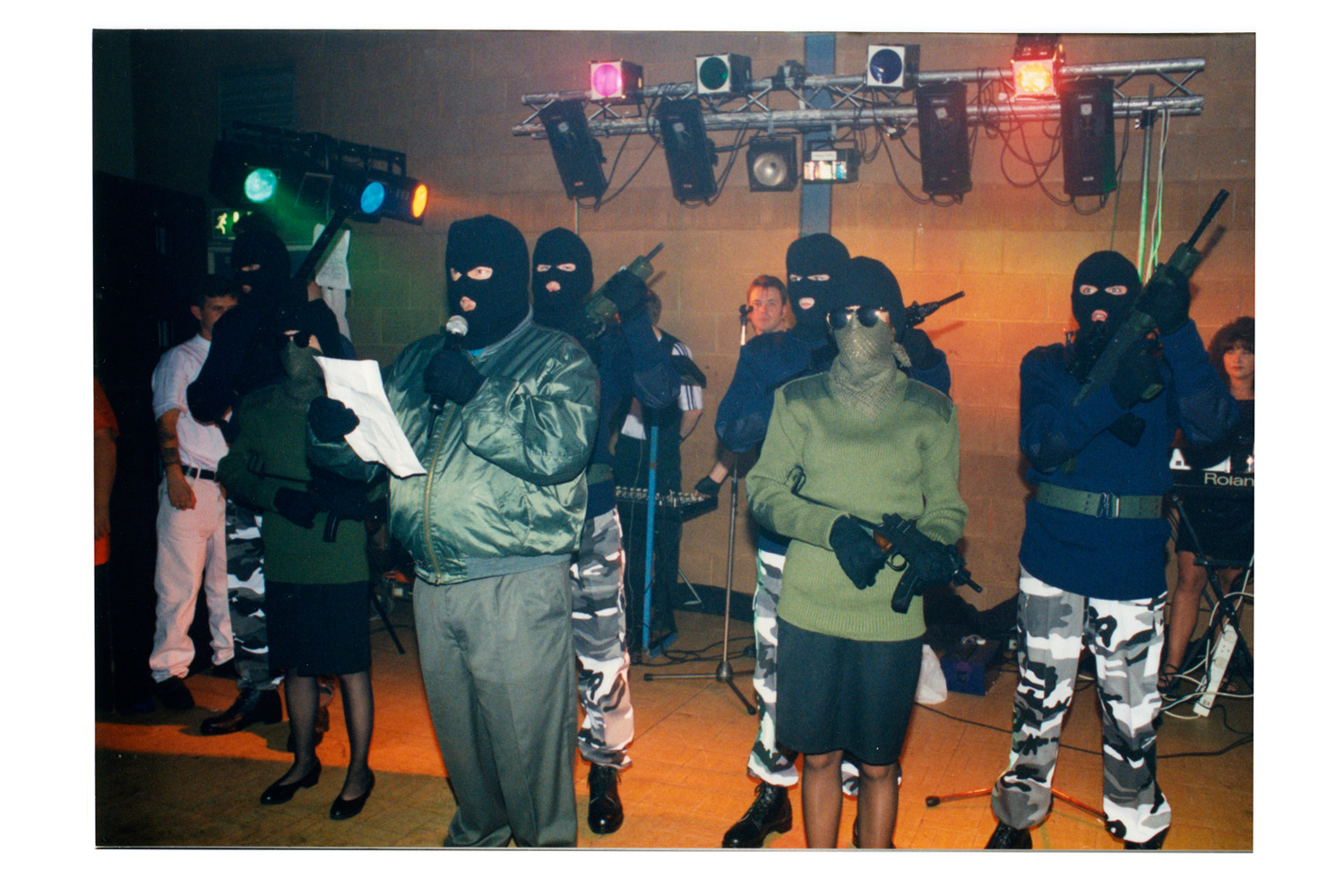

A graffiti-ridden wall dividing Protestant and Catholic communities. A teenage boy defiantly packing drugs into a battered homemade bong. A man gazing at a memorial wreath nailed to a brick wall. The whitewashing of a propaganda mural – the last of its kind. These are the scenes of modern Belfast. The images, both resonant and ordinary, are part of photographer Adam Patterson’s series, Men and My Daddy. The collection of photographs – which features both documented stills from Patterson and found images – tells the story of how the members of Northern Ireland’s largest loyalist paramilitary group, the Ulster Defense Association, are adjusting to life after the notorious Troubles.

“I felt it was a really interesting time; it was a transitional period,” Patterson, who was born in Northern Ireland, said of the country after the fighting had ceased. For decades Northern Ireland was largely characterized by violence and terror as the country divided into two camps: the Protestant unionists and the Catholic nationalists. In 1971, the UDA emerged as a force to be reckoned with, instigating some of the region’s most mobilized fighting. When the conflict was brought to an end and paramilitary groups pledged their commitment to the peace process, the UDA – much like Northern Ireland – was faced with the task of reinventing itself.

Intrigued by the work that was being done, Patterson built relationships with several members of the community. He began documenting one project that focused on repainting the various murals around the region, which featured armed men in what was part of a “fear campaign” established by the UDA. “The idea is to change the murals so they still symbolize the traditions of the area, but not in a violent way,” said Patterson. But soon he became interested in what the reformed men — and their offspring — were dealing with internally as well. Though many were committed to change, Patterson noted that it was a lot easier said than done: “Obviously when people sign up to the peace process minds don’t change overnight.”

As he spent more time at home in Northern Ireland, he came to recognize the different way the country’s youth, who’d only heard of The Troubles secondhand, viewed the process towards peace. “The young people kind of become frustrated that they’ve been cheated out of fighting for this nostalgic idea that’s passed down through the generations,” said Patterson. “They don’t hear the tales of misery or the prison sentences, they only hear these elements of nostalgic stories. They feel like they’ve missed out.” Photographs of youths continuing the traditions of the previous generation — such as building massive bonfires while still being wary of rival youths — attest to the deceptive allure of the country’s history. It’s what Patterson calls a “twisted nostalgia.”

Yet as he became more immersed in his work, Patterson soon felt his own feelings about The Troubles growing complicated as well. “Obviously, I was initially quite apprehensive about it because I didn’t know much about [former UDA members] besides what you’d read in the newspapers which is never good,” he said. “Whether I’ve met these guys or actually think they’re nice guys, is irrelevant to some extent. What the organization stood for and what the organization did was terrible. That’s not excused. But a lot of these guys today would think the same thing.”

Though Patterson maintains that he doesn’t shoot to “change people’s opinions,” after working in his native country he’s come to appreciate the biggest challenge facing these reformed extremists: forging a better path for their sons and daughters to follow.

“It’s about helping young people find a passion,” he says, “so they have something to try and emulate beyond their uncles and forefathers in the very recent history.”

Adam Patterson is a Northern Irish photographer. More of his work can be seen here. Patterson is currently showing work from his project A Very Normal Place at RUA RED in Dublin.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com