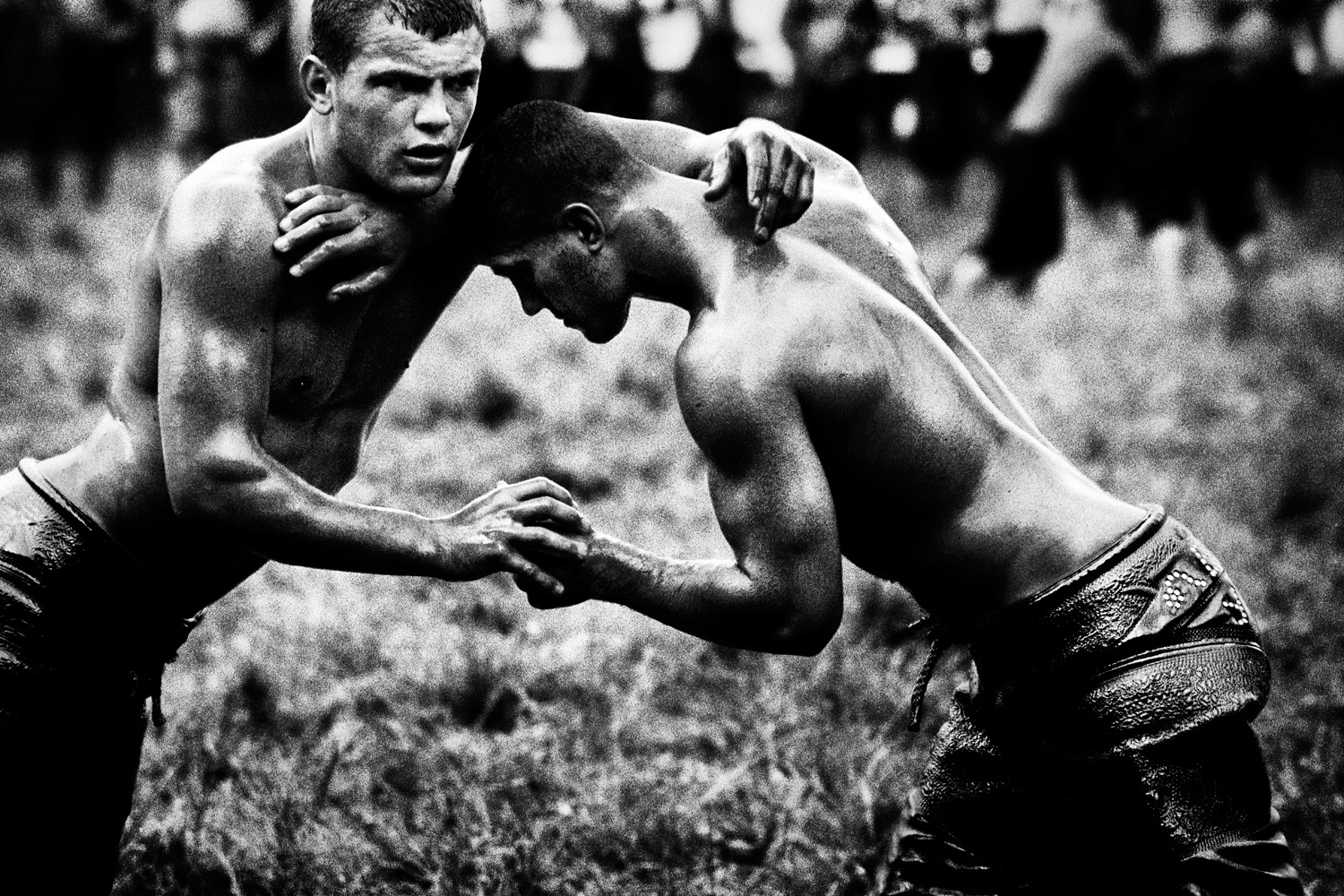

The sport of yağlı güreş, or oil wrestling, is at the heart of Kırkpınar, a festival in the Turkish city of Edirne. Thousands of people will come to see these wrestlers—slick with olive oil—compete in the 651st annual games on July 2. It’ll be a familiar sight for Turkish photographer Pari Dukovic, who attended the event in 2010 and 2011.

“I saw that the sport had an Old World charm to it—the festival, the prayers, the music, the instruments, the outfits,” says Pari, who used to watch the festival’s coverage as a teenager. “I am drawn to subject matter that makes you feel as though you are traveling through time and Kırkpınar fascinated me with its history and how it has remained an integral part of Turkish culture.”

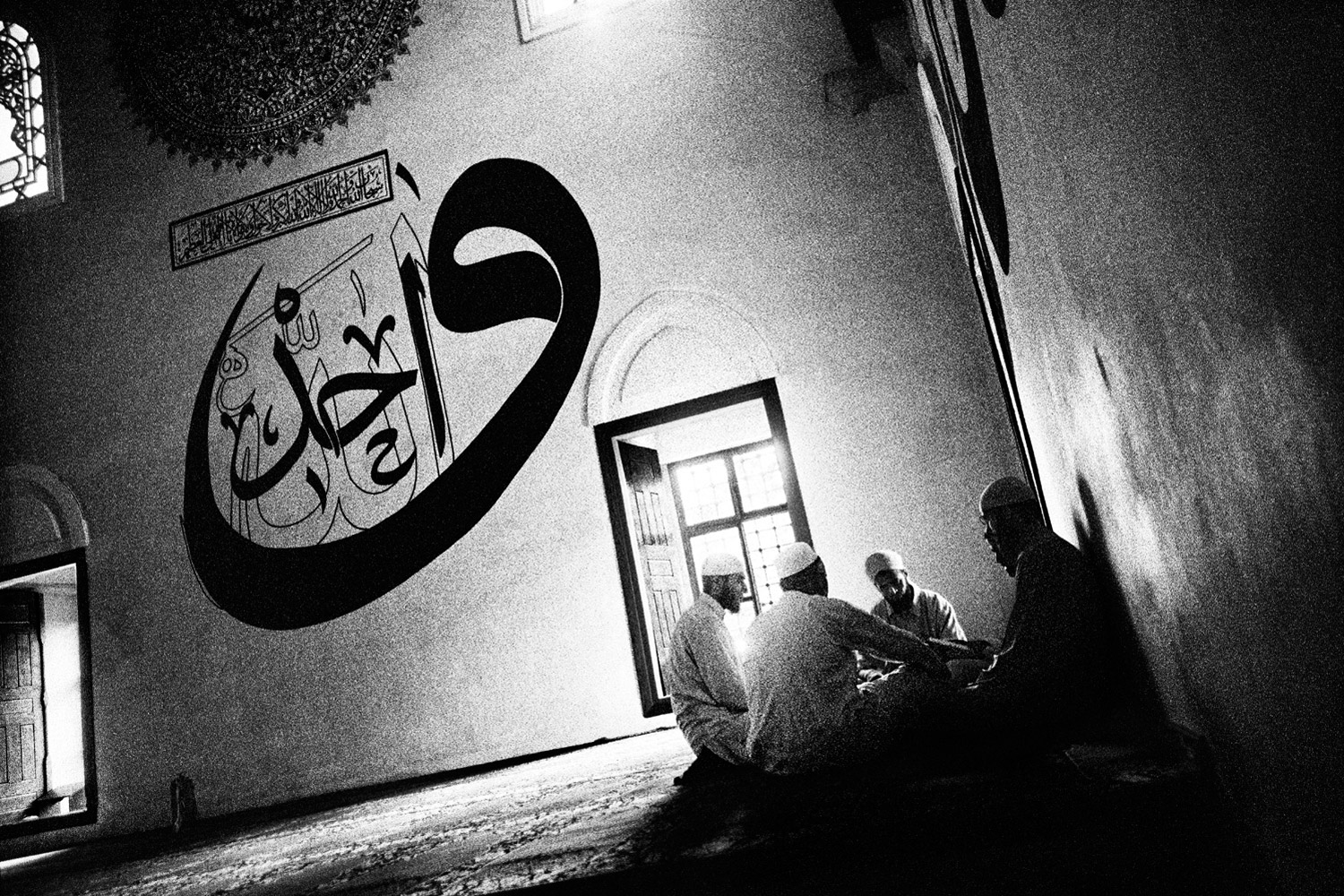

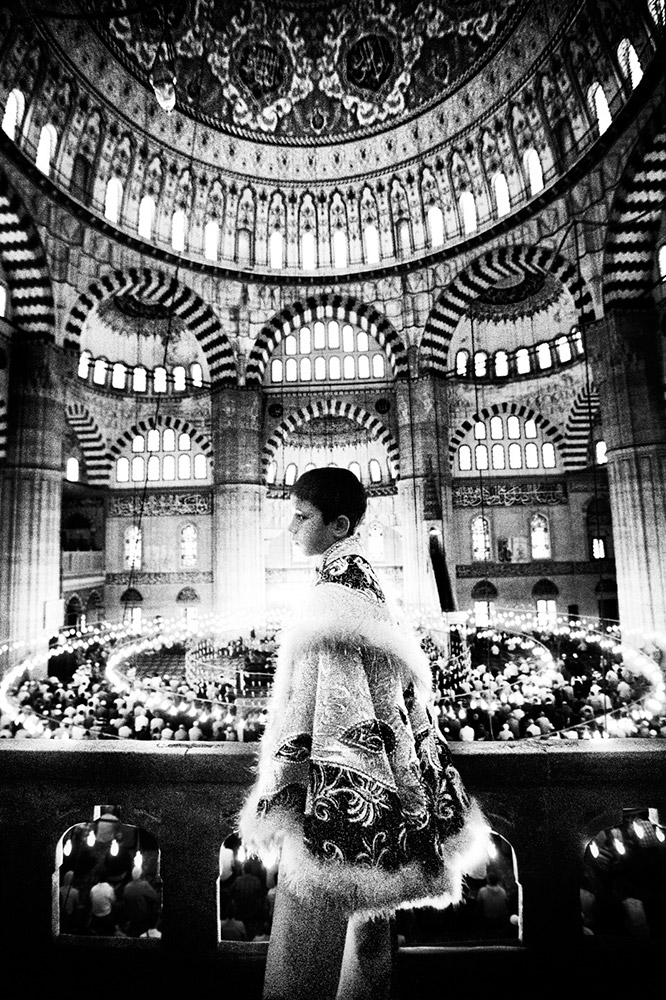

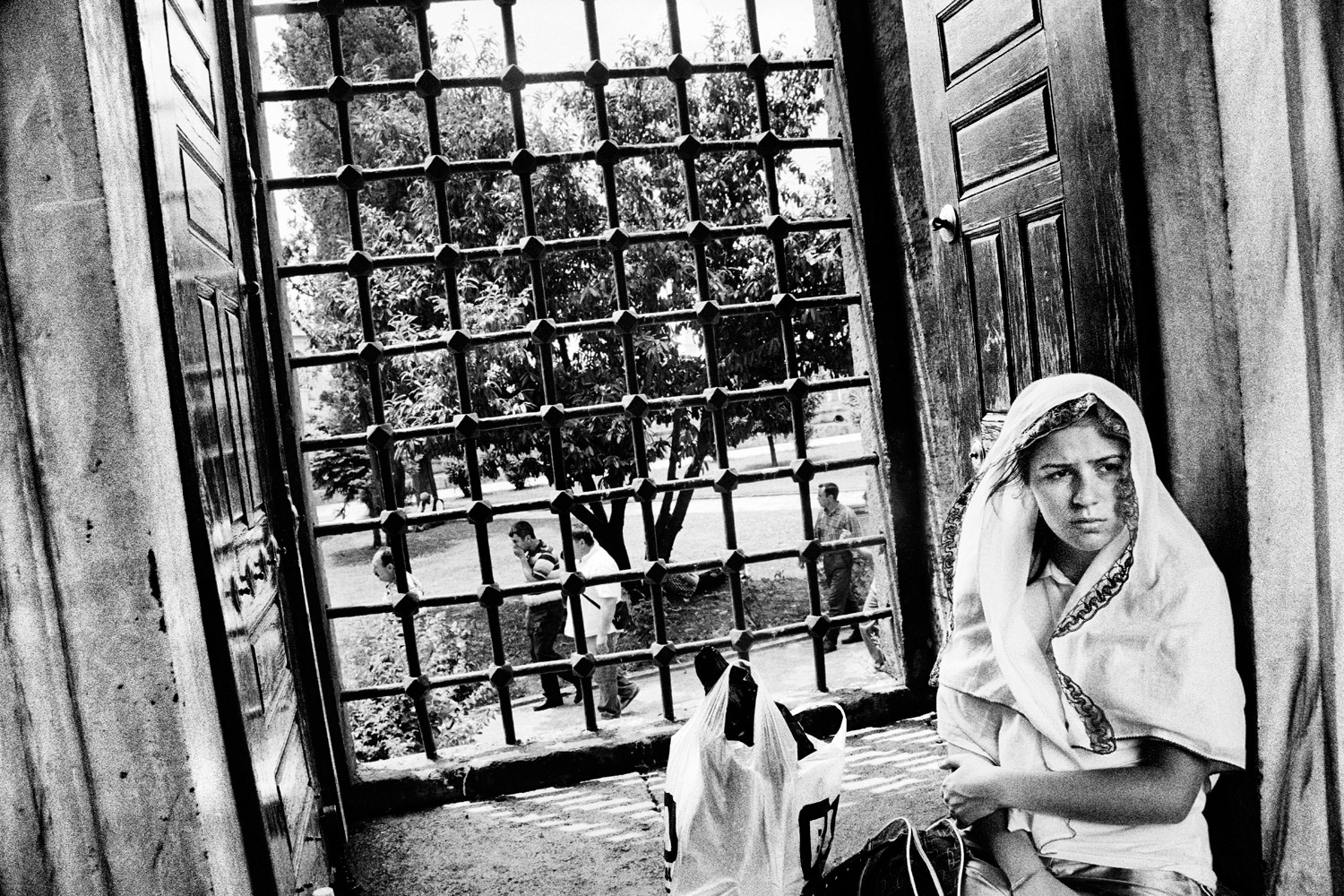

As the festival begins, drum and horn players parade through the city with the sports’ grand prize—the Kırkpınar Golden Belt. The community then meets in the grand 16th century Selimiye Mosque, where the imam gives a sermon in honor of competitors past and present. For the young boys participating in the traditional Turkish coming-of-age ceremony known as Sunnet Dugunu, it’s desirable to celebrate it at the same time as Kırkpınar, as the festival represents to many the ultimate in male achievement. The boy in the mosque in slide #10 wears the ornate cape associated with the ritual.

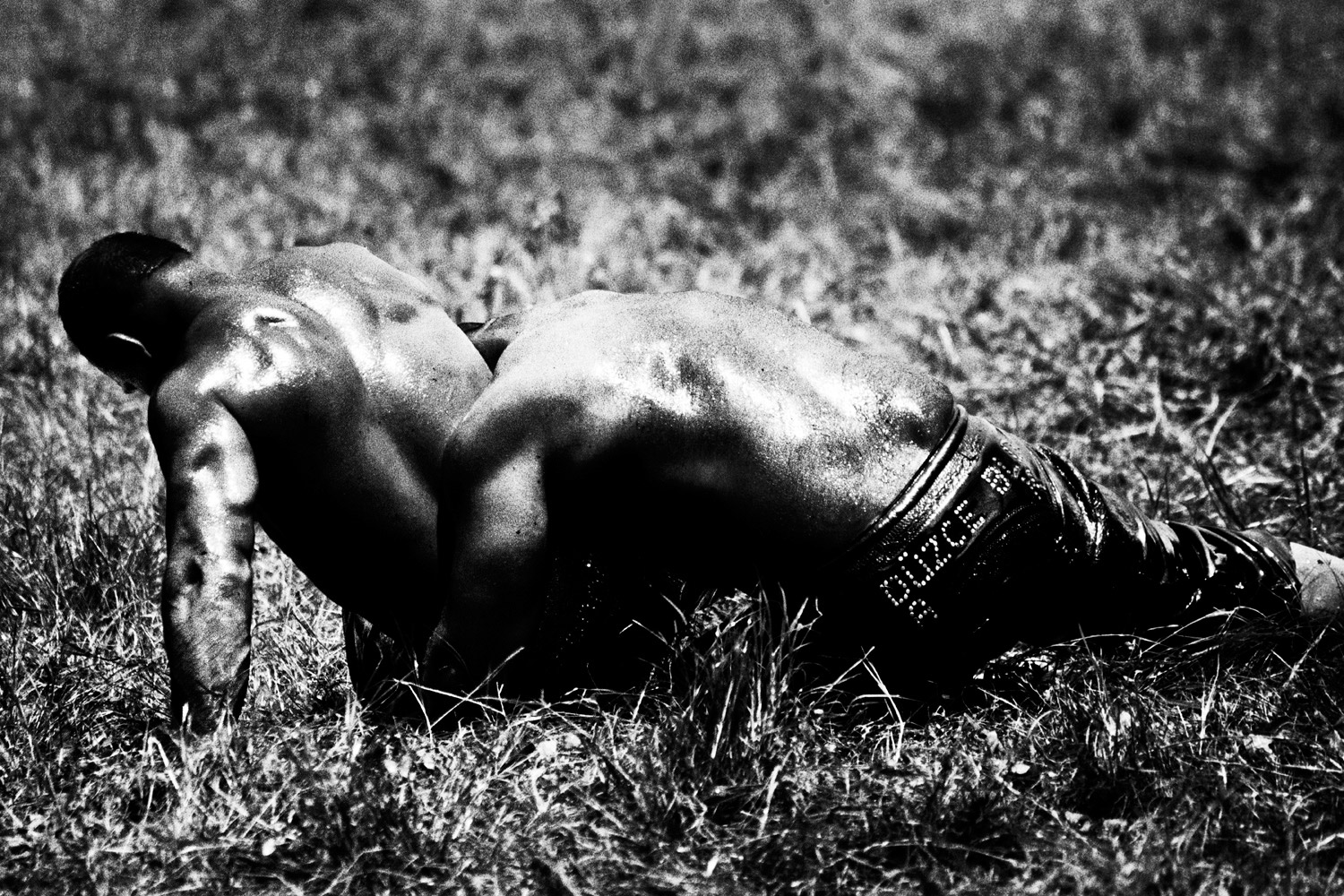

After the sermon, wrestlers pray at the graves of legendary sportsmen and proceed through the streets to the competition field, singing the national anthem. The master of ceremony introduces the wrestlers to the audience, reciting their names, titles and skills in verse. Very few of the wrestlers, who range widely in age, make a living from the sport. Nevertheless, Pari says he got the clear sense that being a part of this event is a dream come true for them. “They train for a whole year and often travel from villages all over Turkey to participate, so becoming a Kırkpınar wrestler is an achievement they take great pride in,” he says. The wrestlers, wearing nothing but short leather trousers, get rubbed down with olive oil. This makes the goal of the match—to throw one’s opponent on his back—all the more difficult. The matches last about 30 minutes each, while the final bout can last up to two exhausting hours.

“I think the dedication that goes into what they do is amazing,” says Pari. “I hope that my photographs stand as visual documents of this tradition and that my respect is captured in these images.”

Pari Dukovic is a New York City based documentary photographer. See more of his work here.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com