Before the 2010 Eyjafjallajökull volcanic eruption, which grounded air traffic in Europe for weeks, few people were probably aware that Iceland averages an eruption once every four years. But while the spewing of hot lava is a frequent event, that doesn’t mean it’s a common one. “When we have eruptions, it’s all over the news,” photographer Ragnar Th. Sigurdsson tells TIME. “Most Icelanders try and go and see the eruptions. We are very excited about it.”

Sigurdsson has spent much of his career photographing Iceland’s volcanic eruptions. As he explained to TIME in 2011, within minutes of an eruption, he’s in a plane to photograph the event from above. “If there would be an eruption right now, I would immediately jump into an airplane to get pictures,” he says. “Then I would go take my trusted Jeep and drive up there with my tripod and stay there. I like much better taking pictures on the ground than in the air. They are more powerful and more exciting.”

After years of recording Iceland’s volcanoes up close, Sigurdsson undertook his latest project, to collect and preserve as many photographs of Icelandic volcanoes as he could find. Along with geophysicist Ari Trausti Gudmundsson, his friend for 25 years, Sigurdsson pored over archives, scanning and preserving hundreds of photos of eruptions on the small Nordic island. They are collected in the recently published book Magma: Icelandic Volcanoes.

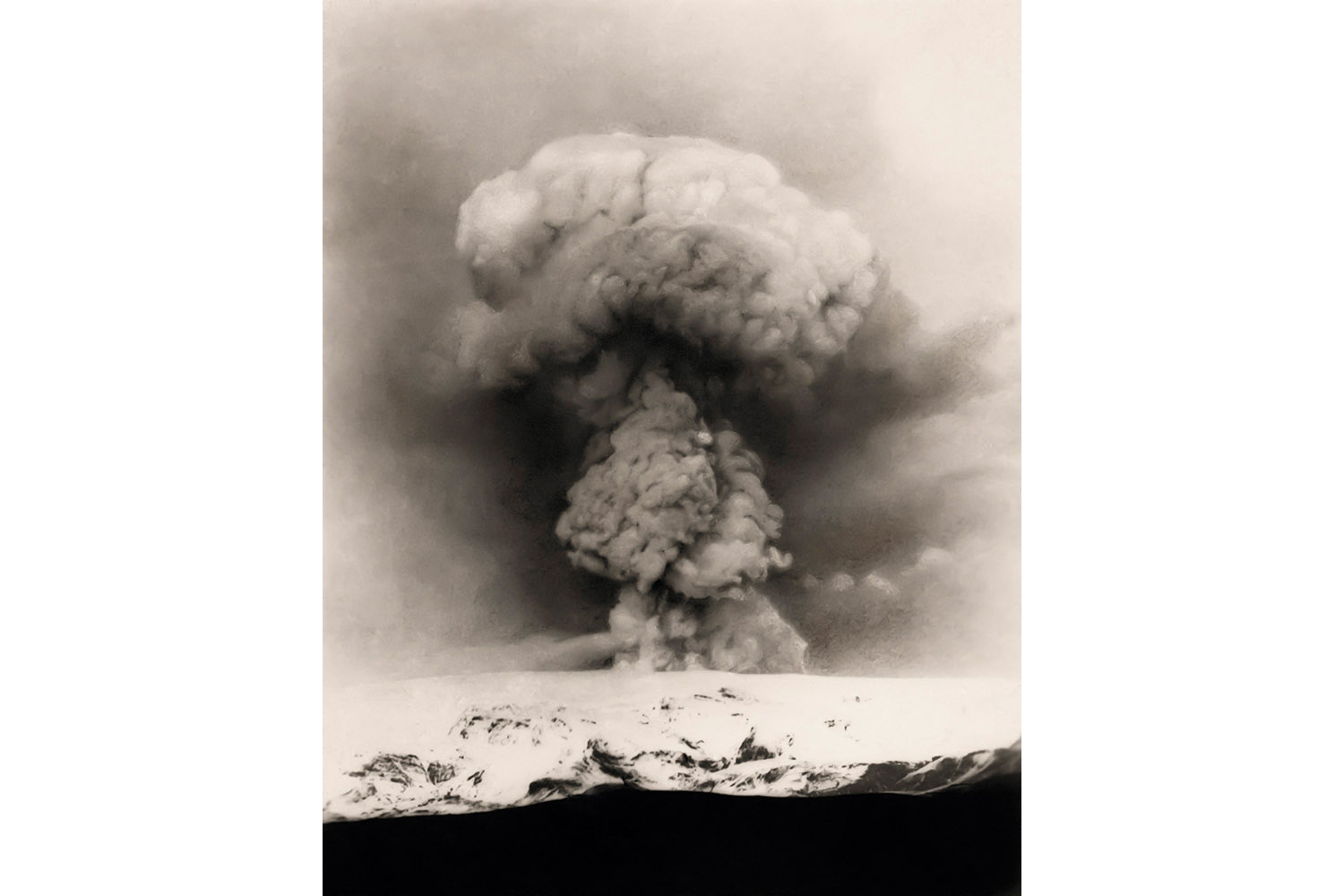

Many of the photos in the collection are exactly what you think a volcano should look like: searing reds and oranges spewing from the ground; black soot careening into the sky. But the book also includes old black and white photos that are equally powerful, classic depictions of geologic explosions that can pack as much power as an atomic bomb. “I’m quite fond of black and white myself,” Sigurdsson says. “Black and white volcano pictures are, maybe not all the time as powerful as the orange ones. If you have a lot of orange and blue colors, it’s a great contrast, the scenes and strong colors.”

Now that he has preserved the history of Iceland’s volcanoes, Sigurdsson is readying for the next eruption. When photographing a volcano, “you have to make decisions on the fly when you have the scene in front of you,” he says. Do you need slow shutter speed, long exposures, or do you need to freeze the action or all of the above? “You have to try everything and use all your knowledge—the key to success is you’re never done,” he says. “I was done when all of my batteries were dead. And I can’t wait for the next eruption.” Given the frequency of the country’s volcanoes, he might not have to wait long to try it out.

Ragnar Th. Sigurdsson has worked as a photographer since age 16. His work is available through Arctic Images. MAGMA: Icelandic Volcanoes is available directly from the publisher.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Inside Elon Musk’s War on Washington Meet the 2025 Women of the Year Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer? Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love 11 New Books to Read in February How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone Cecily Strong on Goober the Clown Column: The Rise of America’s Broligarchy

- Inside Elon Musk’s War on Washington

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- 11 New Books to Read in February

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Cecily Strong on Goober the Clown

- Column: The Rise of America’s Broligarchy

Contact us at letters@time.com