A huge, colorful mural of the men Egyptian youth activists know as “felool”—regime remnants—adorns a building’s wall on Mohamed Mahmoud Street in downtown Cairo. Branching off of the now iconic Tahrir Square, Mohamed Mahmoud leads to the dreaded Interior Ministry. A number of bloody clashes between protesters and Egyptian security forces have taken place here in the year and a half since a popular uprising ended the 30-year dictatorship of Hosni Mubarak and launched the Arab world’s largest country into a tumultuous transition. To Egypt’s budding generation of revolutionary street artists, these walls are prime real estate for political expression like “we buy houses“.

Omar Fathi, the 26-year-old art student, who painted the mural with a set of cheap plastic paints last February, conceived of the idea after a deadly soccer riot had led to another series of clashes between police and protesters, leaving more than 80 people dead. Like much of his art, it was an image borne of frustration. Many of the youth protesters had blamed the ruling military and the police forces under its command for the deadly soccer riot and the ensuing violence as anger spread to the streets. To Fathi, it was further evidence of the state’s failure to govern and protect—something he had grown accustomed to under Mubarak, but that he and other youth activists and members of his “Revolution Artists’ Union” say has only continued under military rule. “Basically it represents the situation we are in, nothing has changed since the fall of the regime,” he says. “It’s the same leadership—the face has changed, but the rest is still the same.”

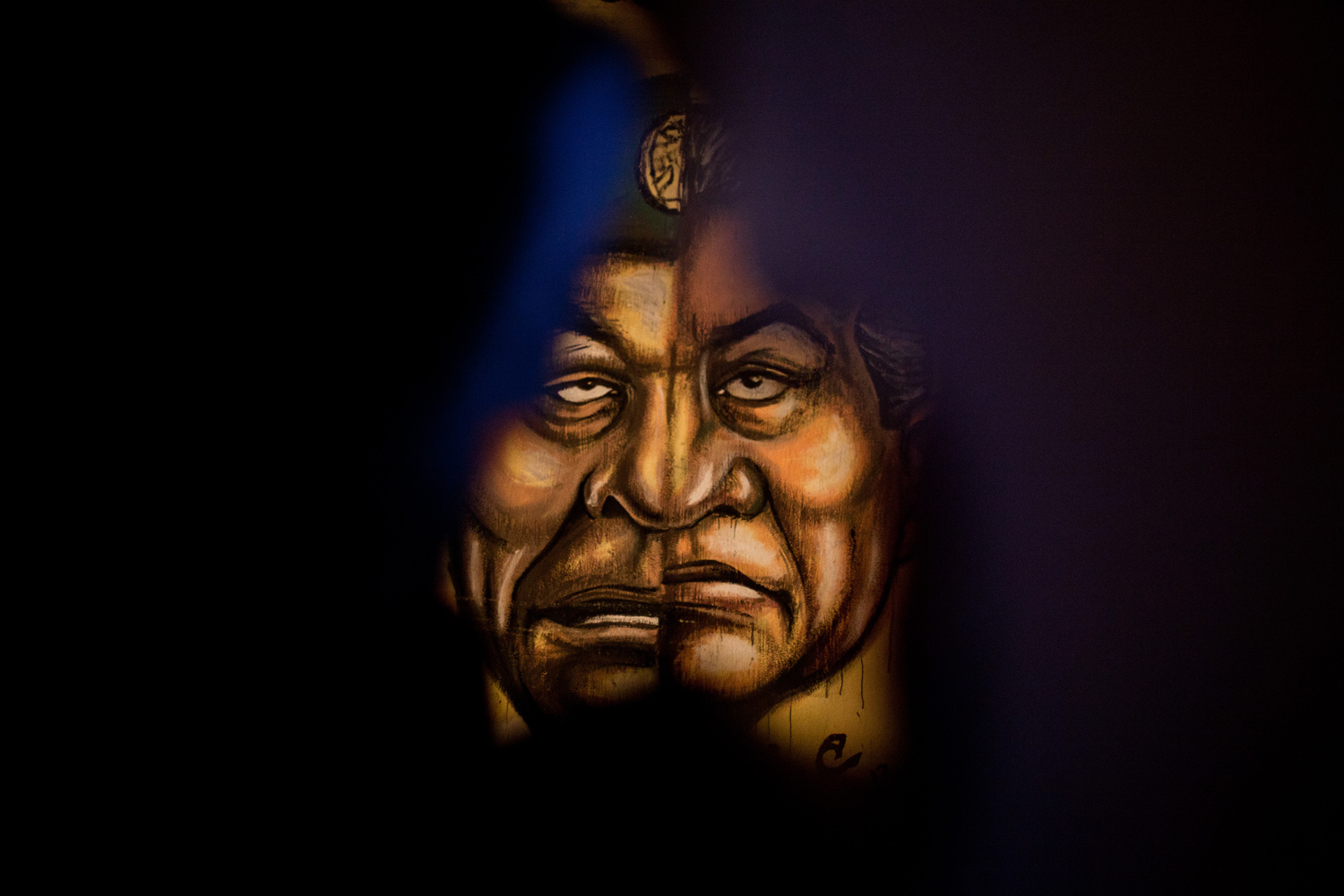

The mural depicts a split face—on the right, the scowling visage of ousted President Hosni Mubarak; and on the left, the man he once appointed to run his military, Field Marshal Mohamed Hussein Tantawi. As the head of Egypt’s powerful military council, Tantawi has been Egypt’s de facto ruler since Mubarak stepped down in February 2011.

Shortly after Fathi painted his masterpiece, someone—he suspects from the military —painted over it. To spite them, he painted it again. When it was painted over a second time, he re-painted it a third, this time adding the faces of two presidential candidates, Amr Moussa, and Ahmed Shafik. Both men had served in Mubarak’s regime. And the run-off to the presidential election this month pit Ahmed Shafik against a candidate from the once-banned Muslim Brotherhood, in a tense face-off that some activists characterized as a battle between the old order and the new; the military regime versus the revolution. In the end, the Muslim Brotherhood candidate Mohamed Morsy won. But Tantawi and his military council have ensured that Morsy only wields certain presidential powers; the military controls the rest. And Fathi says he’ll keep painting. “Our contribution [to the revolution] is to portray the demands of the revolution through art. This has been our role since the eighteen days [of the uprising],” he says. “We serve the revolution through art, and we will keep illustrating our demands.”

Sharaf al-Hourani is a news assistant for TIME Magazine in Cairo.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- TIME’s Top 10 Photos of 2024

- Why Gen Z Is Drinking Less

- The Best Movies About Cooking

- Why Is Anxiety Worse at Night?

- A Head-to-Toe Guide to Treating Dry Skin

- Why Street Cats Are Taking Over Urban Neighborhoods

- Column: Jimmy Carter’s Global Legacy Was Moral Clarity

Contact us at letters@time.com